Pathology of Biliary Tract Cancer

N. Volkan Adsay

David S. Klimstra

Introduction

The components of the biliary tract, that is, the gallbladder, extrahepatic biliary tree, and intrahepatic bile ducts, have fairly similar histologic characteristics; therefore, the pathological classification of the neoplasms arising in these three sites is also similar (1,2,3). In contrast, the risk factors for these neoplasms, which include clinical findings, treatment indications, and biological behavior, may vary. For instance, although adenocarcinomas of the proximal bile ducts have a strong association with primary sclerosing cholangitis (4,5) or anomalous pancreatobiliary duct junction (6,7), gallstones (8) are the main risk factor for gallbladder adenocarcinomas, and parasites (9) are well-established instigators of intrahepatic (peripheral) cholangiocarcinomas. This variability is also partially reflected in molecular alterations, which, although not specific for the histologic subtype of the tumor, may impact the management and prognosis. The various presentations of biliary tract adenocarcinomas also influence the mode by which a specimen is obtained for pathological examination. Many gallbladder adenocarcinomas present with findings of cholecystitis and, thus, are often removed via “routine” cholecystectomy procedures in primary care facilities; in contrast, extrahepatic bile duct lesions are seldom biopsied or resected without a strong suspicion of carcinoma, and this is usually performed in a tertiary care center.

Tumors of the biliary tree are relatively rare, but they are also often problematic diagnostically at both the clinical and the histologic levels. In addition to the rarity of these tumors, which translates to lack of familiarity for most medical disciplines, there are other factors that render biliary tumors problematic:

The extrahepatic biliary tract has complex anatomy in which different tissue types converge in a small area.

This region is relatively inaccessible, which makes it difficult for screening and diagnosis.

Inflammatory conditions of this region closely mimic neoplasia; for example, primary sclerosing cholangitis often forms a cancerlike stricture.

In this chapter, the pathological aspects of biliary neoplasia are discussed, with emphasis being placed on the main malignant tumor type, adenocarcinoma. The topic is discussed by approaching the biliary system as a whole, with brief mention of the site-specific characteristics.

Adenocarcinoma of Pancreatobiliary Type

The vast majority of biliary tumors are adenocarcinomas. In the gallbladder, this neoplasm is designated “gallbladder adenocarcinoma”; in the intrahepatic bile ducts, “cholangiocarcinoma”; and in the extrahepatic biliary ducts, “adenocarcinoma of the extrahepatic bile ducts.” The vast majority of adenocarcinomas are of the generic histologic type referred to as pancreatobiliary because of their morphologic, immunophenotypic, and prognostic similarities to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas.

Adenocarcinomas of the biliary tract are seen predominantly in elderly patients. The association of biliary adenocarcinomas with prior chronic inflammation has been well established, mostly by epidemiologic data showing a high incidence of gallbladder cancer in populations with a high incidence of gallstones or cholecystitis, such as Native Americans (8). Also, the risk of carcinoma is high in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (6,7) (and, thus, with ulcerative colitis [10]). The association of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas with parasites (9) and of extrahepatic adenocarcinomas with choledochal cyst (11) is also presumably a reflection of inflammation-associated carcinoma.

Macroscopic Features and Growth Patterns

Biliary carcinomas have traditionally been divided into four types based on their macroscopic growth pattern: scirrhous constricting, diffusely infiltrative, polypoid, and nodular (12,13,14,15). The constricting and diffusely infiltrative patterns may be difficult to differentiate from chronic inflammatory conditions, especially primary sclerosing cholangitis. Polypoid growth is typically found in papillary or well-differentiated carcinomas, which are associated with a better prognosis. The nodular and scirrhous types have a propensity to infiltrate surrounding tissues and are therefore difficult to resect. The diffusely infiltrating type tends to spread linearly along the ducts. There are significant histologic overlaps among these different growth patterns, and their utility in tumor classification is limited.

On cut sections, the infiltrating component of adenocarcinomas are scirrhous (scarlike), with a firm, white, gritty appearance due to the abundance of desmoplastic stroma (fibrotic tissue reaction associated with infiltrating carcinoma). Necrosis can be seen in larger tumors. Ulceration is common in gallbladder carcinomas (Fig. 35.1). Intraluminal components of biliary carcinomas, especially those with a polypoid gross appearance, may appear more friable, soft, and tan, reflecting the

presence of papillary elements growing into the lumen. Due to the relatively thin wall of the gallbladder and major bile ducts, it is common for small (<1.0 cm) carcinomas to invade deeply into, or through the wall to, adjacent soft tissues, liver, or pancreas. Often the gross limits of the carcinoma are difficult to determine, and the tumor may merge with adjacent areas of inflammation and fibrosis; thus, it can be difficult to grossly assess the margins of surgical resection, necessitating frozen section analysis.

presence of papillary elements growing into the lumen. Due to the relatively thin wall of the gallbladder and major bile ducts, it is common for small (<1.0 cm) carcinomas to invade deeply into, or through the wall to, adjacent soft tissues, liver, or pancreas. Often the gross limits of the carcinoma are difficult to determine, and the tumor may merge with adjacent areas of inflammation and fibrosis; thus, it can be difficult to grossly assess the margins of surgical resection, necessitating frozen section analysis.

FIGURE 35.1. Adenocarcinomas of the biliary tract are usually characterized by a scirrhous, gray-white, firm cut surface. Extension into the liver, as seen here, may cause more sharply demarcated appearance (See also color Figure 35.1). |

Peripheral cholangiocarcinomas and the intrahepatic extension of extrahepatic biliary carcinomas may appear deceptively well demarcated. This allows for easier identification of the boundaries of these carcinomas in hepatic resections. In contrast, carcinomas invading the hilar soft tissue typically have ill-defined borders that are difficult to appreciate. Gallbladder carcinomas are often associated with gallstones. In cases of porcelain gallbladder (16), the wall of the gallbladder may be entirely calcified.

Microscopic Aspects

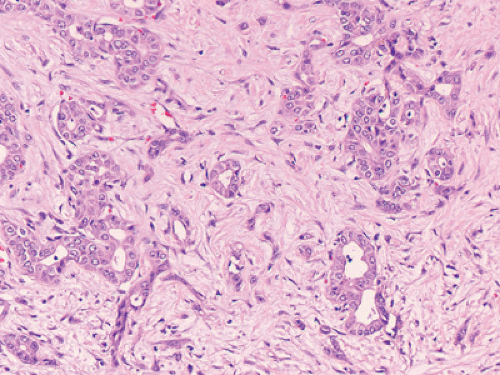

Most biliary adenocarcinomas are of the pancreatobiliary type, characterized by relatively small clusters of cells, often with gland formation, and associated with a desmoplastic or fibrotic stroma (1,2,3) (Fig. 35.2). The glands are often well formed, are lined by cuboidal cells, and show dilated lumina. Often the nuclear grade is unexpectedly high for the degree of glandular differentiation. The cytoplasm may be acidophilic and granular in some cases or pale to clear in others. A variable amount of intracytoplasmic and intraluminal mucin is present; in some, it is readily evident by routine histologic examination, and in others, demonstrable by special stains. Abundant stromal mucin deposition (mucinous or colloid adenocarcinoma) is only seen in rare cases and usually as a focal finding.

FIGURE 35.2. Adenocarcinoma (pancreatobiliary type). Small glandular units lined by cuboidal cells. They are often embedded in a dense, desmoplastic stroma (See also color Figure 35.2). |

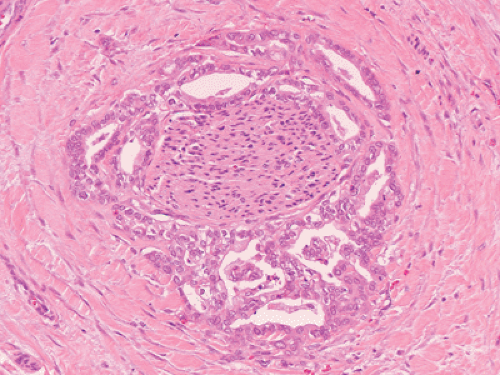

FIGURE 35.3. Adenocarcinoma, perineural invasion. Relatively well-differentiated adenocarcinoma wrapping around a nerve is a common finding in biliary adenocarcinomas (See also color Figure 35.3). |

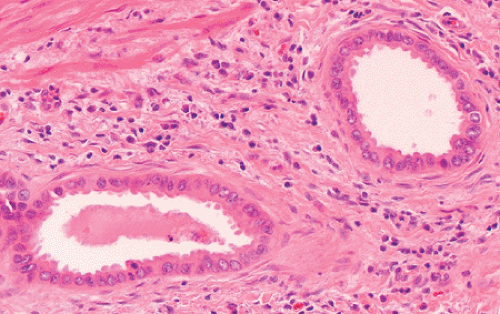

Biliary adenocarcinomas have a highly insidious pattern of spread. Perineural (Fig. 35.3) and vascular invasion (Fig. 35.4) are common, and malignant glands may have a deceptively benign appearance even when they invade these structures. In fact, the distinction of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma from a benign reactive process in this region is one of the more challenging differential diagnoses in surgical pathology.

Tumors that infiltrate the adjacent liver may acquire a more trabecular pattern, presumably by growing along the sinusoidal framework of the liver parenchyma. Entrapped reactive bile ductules and hepatocytes are often present within the tumor, and may create a diagnostic problem in biopsy specimens.

FIGURE 35.4. Adenocarcinoma, vascular invasion. Vascular invasion is commonly detected in adenocarcinomas of biliary tract (See also color Figure 35.4). |

Site-Specific Aspects

The distinctive clinical characteristics of adenocarcinomas occurring in the different regions of the biliary tract are discussed in other chapters of this book, so only a few issues pertinent to pathological aspects are mentioned here. For therapeutic and prognostic purposes, tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tract are separated by their anatomical distribution into upper third (above the cystic duct junction, including both hepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct, and the cystic duct), middle third (upper half of the common bile duct [CBD]) and lower third (distal half of the CBD) (12,14,17,18). The majority of carcinomas in the upper third tend to be the scirrhous-constricting and diffusely infiltrative types. More recent studies have shown that many originate within 5 mm of the cystic duct junction or within the cystic duct itself. Hilar carcinoma located at the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, sometimes referred to as a Klatskin tumor (17,19), has distinctive clinical features. Klatskin tumors usually grow into the liver rather than distally toward duodenum (20). The component that invades the liver is often well demarcated. Carcinomas in the middle third tend to be of the “nodular-sclerosing” type (thickened along a long segment, with a narrow lumen and inflammatory changes in the surrounding tissues) and hence are difficult to differentiate from sclerosing cholangitis. They have a very high propensity for perineural invasion and spread radially into the periductal connective tissue, making curative resection difficult (21). Those carcinomas in the distal third have the best prognosis, partly due to their resectability by pancreatoduodenectomy, and partly due to the fact that some, especially those close to the ampullary region, are composed predominantly of noninvasive papillary elements (1,2,3).

Pathological Differential Diagnosis

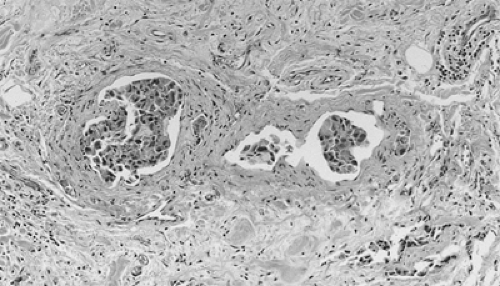

The difficulty at the clinical level of distinguishing biliary adenocarcinomas from benign inflammatory conditions such as sclerosing cholangitis is also valid, perhaps to a greater degree, at the microscopic level (22,23). Reactive changes in the biliary ductules in the wall of the bile ducts can mimic adenocarcinoma. Conversely, biliary adenocarcinomas can be deceptively benign appearing, composed of well-formed glandular elements lined by fairly organized, cytologically bland glandular cells (Fig. 35.5). The distinction of reactive changes in the surface epithelium from dysplasia often proves to be even more challenging, especially because any injury of biliary epithelium (including instrumentation and stent placement) has a tendency to induce marked cytologic changes that mimic those of dysplastic cells. Marked nuclear enlargement, nuclear irregularities, hyperchromasia, loss of polarity, mitotic figures, apoptotic cells, and intraluminal necrosis are findings in favor of a neoplastic process; however, overlaps are common, and sometimes this distinction may not be possible on the basis of biopsies or frozen sections. This differential diagnosis is even more difficult in cytologic specimens, obtained by fine-needle aspiration or endoscopic brushing. The latter poses significant problems for the pathologist, both in terms of the amount of the specimen and the degree of subjectivity in identifying the cytologic features of malignancy versus reactive atypia.

FIGURE 35.5. Adenocarcinoma, well differentiated. In many cases, neoplastic cells exhibit bland cytologic features and well-defined glandular structures, creating a deceptively benign appearance (See also color Figure 35.5). |

As discussed previously, most biliary adenocarcinomas of different sites are also referred to collectively as “pancreatobiliary” due to striking morphologic and biological similarities. For this reason, based on microscopic findings alone, it is impossible to determine from which part of the biliary tract such a tumor has arisen or whether it may be of pancreatic ductal origin. Carcinomas of other foregut derivative organs, in particular those of the gastroesophageal region, are also quite similar to pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinomas.

Peripheral cholangiocarcinomas can also be difficult to distinguish from primary hepatocellular carcinomas. The presence of true glandular elements, mucin and sclerotic stroma, are common findings in biliary carcinomas and are typically lacking in hepatocellular carcinoma. In contrast, hepatocellular carcinomas may have intracellular bile. Other distinctive features of hepatocellular carcinomas, including the solid and trabecular growth pattern, centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli, and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm are usually enough to make the distinction. Further complicating this differential diagnosis are “mixed” carcinomas in which cholangiolar and hepatocellular differentiation coexist.

Carcinomas of the CBD may be difficult to distinguish from ampullary, pancreatic, and duodenal neoplasms because the tumors of these sites readily infiltrate neighboring structures due to their close proximity. In such cases, determination of the primary site depends on locating the center of the tumor, and this can often be best achieved by close correlation of the radiographic and gross findings. In addition, if present, in situ (or preinvasive) neoplasia may be a clue for the site of origin, although early neoplastic changes in the pancreas (pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia) are extremely common and may be present even when the primary carcinoma is in the bile duct. In this complex region, it is important to evaluate the origin of the carcinoma (by site) separately from the type of the carcinoma; for example, ampullary carcinomas may be of pancreatobiliary type. However, intestinal-type carcinomas in this region are more likely to be either ampullary or duodenal in origin.

Biliary carcinomas metastatic to other sites may mimic the primary tumors of those organs. In particular, metastases to the ovary are often cystic and can be mistaken for primary ovarian mucinous cystic neoplasms (24), and pulmonary metastases can resemble mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinomas. Metastases to the liver periphery from hilar biliary carcinomas can be nearly impossible to distinguish from metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Immunohistochemical and Molecular Characteristics

Biliary adenocarcinomas typically express CEA, CA19–9, MUC1, MUC5AC, CK19, and CK7 (1,2,3). On occasion, these markers can be helpful in the differential diagnosis from other malignancies that do not express these markers (e. g., hepatocellular carcinoma). However, none of these stains is specific

enough to be useful in the distinction of biliary adenocarcinomas from adenocarcinomas of other organs. However, some metastases to the liver express specific markers not found in biliary adenocarcinoma, such as thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in pulmonary adenocarcinomas, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in prostatic primaries, and hormone receptors in mammary or Müllerian carcinomas. Mutations at codon-12 of the KRAS oncogene, which are seen in >90% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, are much less common in biliary adenocarcinomas (25), and the incidence of KRAS mutation appears to decrease from distal to proximal along the biliary tree. Similarly, loss of DPC4 is also less common in biliary than in pancreatic adenocarcinomas (26). More than half of the cases have abnormal expression of p53. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 8p, 9q, and 18q, and amplification of c-erbB-2 is also reported in more than half. Again, none of the genetic alterations of biliary adenocarcinomas are sufficiently specific to be useful diagnostically.

enough to be useful in the distinction of biliary adenocarcinomas from adenocarcinomas of other organs. However, some metastases to the liver express specific markers not found in biliary adenocarcinoma, such as thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) in pulmonary adenocarcinomas, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in prostatic primaries, and hormone receptors in mammary or Müllerian carcinomas. Mutations at codon-12 of the KRAS oncogene, which are seen in >90% of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas, are much less common in biliary adenocarcinomas (25), and the incidence of KRAS mutation appears to decrease from distal to proximal along the biliary tree. Similarly, loss of DPC4 is also less common in biliary than in pancreatic adenocarcinomas (26). More than half of the cases have abnormal expression of p53. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosomes 8p, 9q, and 18q, and amplification of c-erbB-2 is also reported in more than half. Again, none of the genetic alterations of biliary adenocarcinomas are sufficiently specific to be useful diagnostically.

Other Types of Carcinomas in the Biliary Tract

There are other types of adenocarcinomas in the gallbladder and biliary tract that are histologically distinct from the pancreatobiliary-type adenocarcinomas (1,2,3,27).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree