Pancreaticoduodenectomy With or Without Pylorus Preservation

Harish Lavu

Charles J. Yeo

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSPancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a complex surgical procedure designed to treat benign and malignant diseases of the periampullary region. (In many institutions the operation is referred to as the Whipple operation or Whipple procedure.) The most common of the malignant periampullary lesions treated by PD is pancreatic adenocarcinoma (85%), followed by distal common bile duct cholangiocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, and duodenal adenocarcinoma. Taken together, these four tumors affect approximately 50,000 individuals per year in the United States. A host of other less common cancers can arise from the periampullary region including neuroendocrine tumors, pancreatic cystadenocarcinomas, acinar cell and squamous cell carcinomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, sarcomas, and lymphomas. In addition, a number of benign neoplasms as well as chronic pancreatitis can also be treated with PD. Finally, in rare circumstances, PD may be performed for isolated metastases to the periampullary region, or for blunt or penetrating trauma to the pancreaticoduodenal region.

Despite the differences in underlying tumor pathology, many malignant diseases of the periampullary region share similar clinical presentation, preoperative assessment, and surgical treatment strategy. Due to the difficulty and risk in obtaining a preoperative tissue diagnosis, the precise histologic tumor type is often unknown prior to surgical resection.

General contraindications to PD include known metastatic disease outside of the resection zone, locally advanced disease that is involving the mesenteric vasculature [typically the portal vein (PV) or superior mesenteric artery (SMA) or superior mesenteric vein (SMV)], and severe medical comorbidities which preclude safe anesthesia and surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGThe goal of preoperative evaluation in patients undergoing PD is to accurately assess tumor resectability for appropriate surgical preparation and patient counseling.

Preoperative assessment for PD should begin with a complete medical history, with special emphasis on a past history of chronic pancreatitis, or a family history of gastrointestinal cancer. A thorough physical examination may note scleral or cutaneous icterus if the patient has common bile duct obstruction. Significant weight loss is not an uncommon finding. Enlarged left supraclavicular (Virchow’s) or periumbilical (Sister Mary Joseph’s) lymph nodes or a perirectal tumor mass (Blumer’s shelf) represent uncommon findings of disease dissemination. Laboratory evaluation should include complete blood count, electrolyte panel, liver function tests, coagulation profile, tumor markers [carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)], and serum albumin measurement to assess nutritional status.

Patients are educated at the initial office evaluation regarding the indications for surgery and undergo the informed consent process. The anatomy, operative procedure, and postoperative care plan are outlined in detail. Patients are introduced to our clinical pathway for postoperative care that is designed to improve patient safety and reduce perioperative morbidity, mortality, and length of stay.

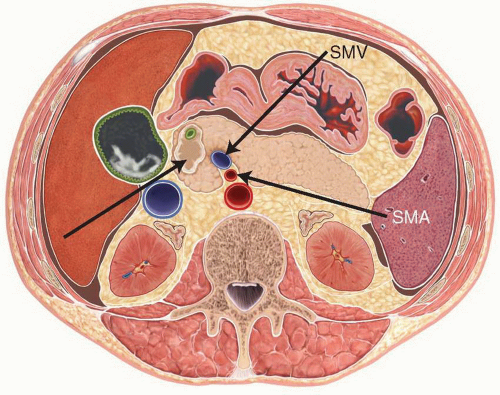

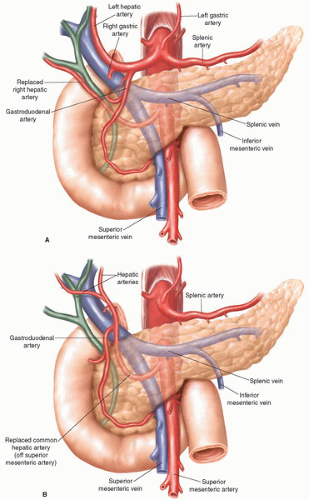

Three-dimensional contrast enhanced thin section multidetector computed tomography (pancreas protocol 3D-CT) with oral ingestion of water has evolved to become our most valuable imaging modality for the diagnosis and preoperative staging of periampullary disease (Fig. 2.1). It allows for a finely detailed assessment of periampullary tumors, and importantly delineates their relationship to the major visceral vasculature. Patients who have tumor abutment greater than 90 degrees of the celiac axis or SMA, or who have greater than 180-degree involvement of the SMV or PV are typically considered to have locally advanced disease, because of the high likelihood of a margin positive resection if they were to undergo an attempt at PD. Patients in this locally advanced group are referred for neoadjuvant treatment (typically protocol-based chemoradiotherapy) prior to surgical resection. Pancreas protocol 3D-CT arterial reconstructions give important preoperative information by identifying vascular anatomic variants, such as replaced right hepatic artery from the SMA or atherosclerotic celiac stenosis, allowing for a safer operation (Fig. 2.2). Pancreas protocol 3D-CT may also detect distant metastatic disease to the liver or the peritoneum, though the sensitivity declines for lesions less than 1 cm in size.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an effective tool whose use has increased in recent years in the evaluation of periampullary malignancies. MRI has an improved safety profile compared to pancreas protocol 3D-CT in patients who have an intravenous contrast allergy or chronic renal insufficiency. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) allows for detailed imaging of the pancreatic and biliary ductal systems and is particularly useful in the assessment of pancreatic cystic disease, where it can delineate communication with the main pancreatic duct in intra-ductal papillary

mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), or absence of ductal communication in mucinous cystic neoplasia (MCN) or serous cystic neoplasia (SCN).

mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), or absence of ductal communication in mucinous cystic neoplasia (MCN) or serous cystic neoplasia (SCN).

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a procedure that allows for direct ultrasound imaging of the periampullary region through the walls of the gastric antrum and duodenum. It offers real-time imaging of the tumor and surrounding lymph nodes, can determine the relationship of the tumor to the visceral vasculature, and provides the ability to obtain tissue via ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (FNA). EUS is highly operator dependent, and requires skilled application and interpretation of the ultrasound images for reliable results. EUS has a higher yield in obtaining a tissue diagnosis than cytologic biliary or pancreatic brushings from endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In patients with unresectable disease, EUS with FNA is an efficient and safe method for obtaining a tissue diagnosis to allow referral for protocol-based chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy. In patients with clearly resectable periampullary abnormalities, a preoperative tissue diagnosis is not required in most cases, as the results of FNA (whether positive or negative) often do not alter the decision to proceed to surgical resection, and the low but measurable risk of procedure-related complications (pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding) may delay surgical intervention.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan is a diagnostic tool whose use is still being defined in the assessment of periampullary malignancy and it is not routinely recommended. PET utilizes a radio-labeled fluoro-deoxyglucose substrate which is preferentially taken up by tumor cells. This functional image can be useful in identifying occult metastatic lesions, but has a relatively high false-positive rate (typically in cases of inflammation or infection). When PET is fused with the cross-sectional images from a CT scan (PET-CT), the combined images can give functional and anatomic tumor staging details. PET scans are not currently the standard of care for preoperative staging of periampullary malignancies, but can aid in the evaluation of suspicious hepatic lesions, or in post-resectional surveillance of disease recurrence.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUEPatient Preparation

The standard steps performed during a PD at our institution are outlined below. It is important to remember that the sequence of steps can be altered and frequently are, as needed, to facilitate the safe exposure and removal of the Whipple specimen.

The patient is prepared for PD with a clear liquid diet on the day prior to surgery. We have abandoned the use of preoperative mechanical bowel preparation in our practice. An endotracheal tube, nasogastric tube, urinary catheter, and appropriate monitoring lines are placed. Prophylactic subcutaneous heparin (5,000 units), lower extremity hose, and sequential compression devices are employed to limit the occurrence of deep venous thrombosis. Epidural catheters are not used, except in rare circumstances. Prophylactic antibiotics (typically cefoxitin 2 g intravenously) are administered within 30 minutes of the incision. The operation is performed in the supine position. The abdomen is clipped and prepped with chlorhexidine from nipples to pubis. In cases where superior mesenteric or portal venous resection or reconstruction is planned, the left neck and bilateral groins and thighs are clipped and prepped as well, to allow access to the left internal jugular vein and saphenous veins respectively, which may be needed for the visceral venous reconstruction.

Technique—Resection (Extirpative Phase)

A midline incision is most commonly made from the tip of the xiphoid process to the umbilicus. A Bookwalter retractorTM is used for exposure. The abdominal cavity is thoroughly explored for occult metastasis, with assessment of the liver, celiac axis region, base of the transverse mesocolon, intestines, and all peritoneal surfaces. Suspicious

lesions outside of the resection zone should be sampled by frozen section examination to rule out distant spread.

lesions outside of the resection zone should be sampled by frozen section examination to rule out distant spread.

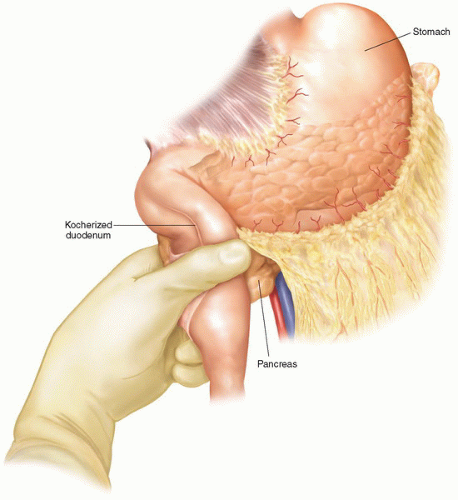

Figure 2.3 After wide kocherization of the duodenum, the pancreatic head is elevated out of the retroperitoneum and the tumor mass is palpated, to help determine its relationship to the SMA. |

Very rarely we will perform an extended right subcostal incision which may facilitate exposure of the right upper quadrant and pancreatic head, particularly in patients who have a short trunk, are morbidly obese, or may require additional hepatic procedures.

The duodenum is widely kocherized by releasing it from the retroperitoneum and elevating the head of the pancreas ventrally off the underlying vena cava. This allows for palpation of the tumor and determination of its relationship to the SMA (Fig. 2.3). Although this is a useful step, it is important to realize that preoperative pancreas protocol 3D-CT scan imaging almost always defines the extent of vascular involvement better than such direct palpation at this point in the procedure.

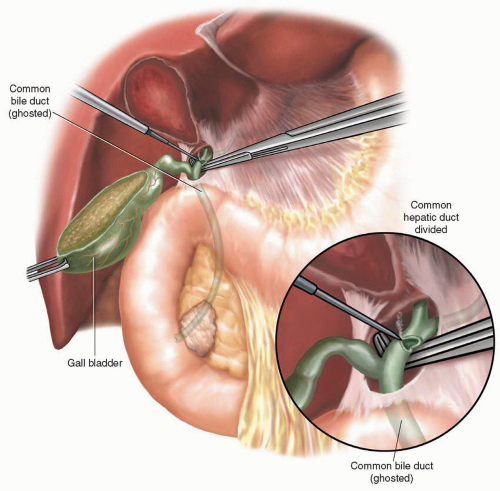

The gallbladder is resected via the “dome down” technique, ligating the cystic duct and artery separately, using 2-O silk ties. The gallbladder can be removed at this point or may be left attached, to be removed later with the Whipple specimen. The gastrohepatic ligament is partially divided with electrocautery, while small vascular and lymphatic bundles are secured with 2-O silk ties and divided.

Further dissection within the hepatoduodenal ligament allows for identification of the proper hepatic artery and its branches, and encirclement of the common hepatic duct with a vessel loop. Care should be taken at this point to identify a replaced right hepatic artery if present, which often lies lateral and posterior to the common hepatic

and common bile ducts. The common hepatic duct is divided with a knife blade (if small) or with electrocautery (if dilated and thick walled) (Fig. 2.4). If either a plastic or metallic biliary endoprosthesis is encountered during the division of the common hepatic duct, it is removed at this point. A bulldog vascular clamp is placed on the proximal common hepatic duct to limit bile spillage until reconstruction begins. Early division of the common hepatic duct and further division of the surrounding lymphatics with their caudal retraction facilitates exposure of the anterior and lateral surfaces of the PV, which can be followed down to the superior border of the pancreatic neck.

and common bile ducts. The common hepatic duct is divided with a knife blade (if small) or with electrocautery (if dilated and thick walled) (Fig. 2.4). If either a plastic or metallic biliary endoprosthesis is encountered during the division of the common hepatic duct, it is removed at this point. A bulldog vascular clamp is placed on the proximal common hepatic duct to limit bile spillage until reconstruction begins. Early division of the common hepatic duct and further division of the surrounding lymphatics with their caudal retraction facilitates exposure of the anterior and lateral surfaces of the PV, which can be followed down to the superior border of the pancreatic neck.

The gastroduodenal artery (GDA) is identified within the hepatoduodenal ligament and is test clamped prior to its division, to ensure maintenance of proper hepatic artery flow to the liver. A Doppler probe may assist in this maneuver. This step ensures that there is no celiac origin occlusion with preferential proper hepatic artery filling via the GDA, originating from the SMA. The GDA is divided between 2-O silk ties and complimented by a 3-O silk suture ligature on its retained side (Fig. 2.5). A plane is then created posterior to the pancreatic neck and anterior to the PV at their interface, at the superior boundary of the pancreas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree