PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ The etiology of pancreatitis should be investigated. Patients with biliary pancreatitis should be considered for cholecystectomy with cholangiography at the time of pancreatic debridement. A significant number of patients will have idiopathic cause; current data implicates microlithiasis and/or sludge in many of these cases. Therefore, strong consideration should be given to cholecystectomy if technically possible and safe at the time of debridement.

■ NP patients have widely variable physiologic condition prior to necrosectomy. On two ends of the spectrum, a patient may be acutely ill with systemic sepsis and require debridement urgently for infectious control. On the other hand, many patients may be “walking wounded”—that is to say, they are home from the hospital managing some oral alimentation and are in reasonable physical health; however, they remain moderately to profoundly symptomatic.

■ All efforts should be made to optimize nutritional and physical condition prior to pancreatic debridement. The clinician should understand that objective nutritional values will never normalize with a volume of necrotic tissue in the retroperitoneum generating a persistent inflammatory response. Enteral alimentation is ideal; parenteral nutrition may be necessary to supplement caloric and protein intake.

■ It must be emphasized that multiple approaches are available to treat NP patients. The disease is extremely heterogeneous and no one intervention fits all patients. Ideally, a multidisciplinary team consisting of surgeons, interventional endoscopists, and interventional radiologists are invested in evaluating these patients. One doctor must be responsible for the long-term care of these patients as the recuperation typically encompasses 6 to 12 months or longer.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ A current cross-sectional image—that is, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan—of the abdomen and pelvis is critically important to use as a road map guiding debridement.

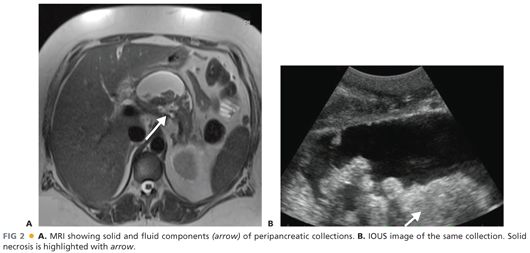

■ An important diagnostic consideration involves estimating the volume of solid material (as opposed to fluid) in the peripancreatic collection. MRI is more accurate than CT in making this estimation. Ultrasound may be most accurate; however, transabdominal ultrasound is plagued by artifact from hollow viscus. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an excellent modality; however, it requires sedation and is moderately invasive. FIG 2 illustrates MRI and ultrasound images.

■ Endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) is most accurate in defining pancreatic ductal anatomy and, specifically, the presence of disrupted main pancreatic duct. If ERP is undertaken in the setting of NP, it should be done a short time before planned debridement, as ERP has a high chance of contaminating what otherwise may be sterile necrosis. Fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis is relatively sensitive in diagnosing infection. This modality is not commonly necessary or used in contemporary practice.

■ Transabdominal ultrasound of the gallbladder should be performed to diagnose stones or sludge and inform the need for cholecystectomy.

■ Broad-spectrum empiric antibiotic treatment is not recommended currently. Antibiotic therapy should be reserved for documented infections with a discrete endpoint in treatment.

■ NP patients have an extremely high (56%) incidence of venous thromboembolic events. Screening duplex ultrasonography should be considered in all NP patients.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

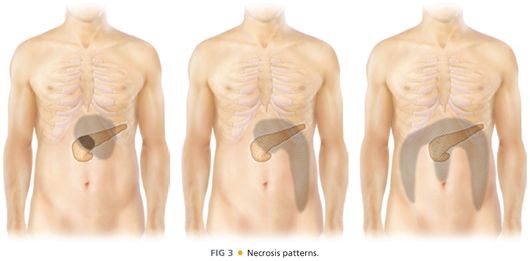

■ Perhaps the most important concept regarding NP is that this disease is extremely heterogeneous. The intervention/operative approach is dictated primarily by anatomic distribution of necrosis, involvement of the pancreatic parenchyma by necrosis, and specific individual clinical situation.

■ Treatment approaches include percutaneous drainage, endoscopic drainage, a combination of percutaneous and endoscopic approaches, retroperitoneal debridement (videoscopic-assisted retroperitoneal debridement [VARD] or sinus tract necrosectomy), surgical transgastric approach, or traditional open operative debridement with external drainage.

■ FIG 3 illustrates typical patterns of necrosis. The image on the left with necrosis confined to the lesser sac may be approached through the posterior stomach either endoscopically or surgically. The middle image with necrosis extending down the left paracolic gutter may be best approached from the retroperitoneum (VARD). The image on the right with necrosis extending down both paracolic gutters and/or the small bowel mesentery root poses a challenging problem. This group also includes patients with pancreatic head involvement. These patients may be best approached by open operative debridement.

■ Definitive intervention should not be undertaken earlier than 4 weeks from the incident episode of pancreatitis.

TECHNIQUES

Goals of pancreatic debridement are shown in Table 1.

OPEN NECROSECTOMY

Exposure

■ The patient may be approached through the midline or a low transverse incision, which provides superb access to the upper abdomen.

■ Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) should be performed prior to disrupting any of the collections. IOUS provides important information about volume of solid necrosis.

■ The surgeon should review recent cross-sectional image immediately before operating; this is a good “road map” directing debridement as well as to refresh memory of danger spots. Specific attention should be paid to the relationship of necrosis to the superior mesenteric and portal veins.

■ A moderate amount of oozing from the diffuse inflammatory process is common. Infracolic adhesions, particularly to the undersurface of the transverse mesocolon, are quite common; these should be divided with careful blunt dissection as well as sharp dissection.

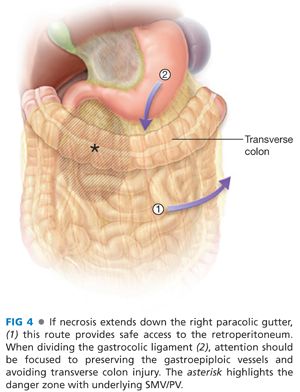

■ The gastrocolic ligament should be divided. The inflammatory response commonly foreshortens the gastrocolic ligament and attention should be paid not to injure either the gastroepiploic vessels or the transverse colon wall.

■ Lesser sac necrosis is always more cranial than it may seem.

■ If necrosis extends down the paracolic gutters, these provide a reasonable and safe point of entry into the retroperitoneum. Debridement should progress from lateral to medial, paying special care to the known position of the superior mesenteric vein and portal vein around the pancreatic head (FIG 4).

■ Catastrophic hemorrhage may occur from inadvertent vigorous debridement in the area of the superior mesenteric vein/portal vein (SMV/PV). The wall of the vein is weak from the inflammatory process. Proximal and distal vascular control is challenging because of the inflammatory process and in a desperate circumstance, applying a long straight vascular clamp across the porta hepatis and root of the small bowel mesentery may be a life-saving maneuver, allowing time to ligate the SMV/PV.

■ It is important to release the colic flexures to provide full exposure of the upper retroperitoneum.

■ Samples of the peripancreatic collection are commonly sent for Gram stain, aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal cultures.

Debridement

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree