Fig. 18.1

This image shows the hand after placement through the HALS port in a natural anatomic configuration. This position will rarely be used

Fig. 18.2

The wrist has been flexed or extended to place the hand in a useful position that will facilitate a better camera view

Fig. 18.3

The wrist has been flexed or extended to place the hand in a useful position that will facilitate a better camera view

The Difficult Splenic Flexure

There are several factors that make splenic flexure mobilization a challenging task. The following are common variants that increase the technical difficulty associated with flexure takedown: a very high flexure, a flexure intimately attached to the spleen via a short and vascular lienocolic ligament, association with a very fatty and heavy omentum, association with extensive congenital omental attachments to the left colon, and complex fusion between the omentum and the transverse mesocolon. For all of these reasons, it is helpful to get as good of an understanding of the anatomy or course of the splenic flexure before beginning a dissection.

There are a few approaches available to the surgeon, and often the use of a combination of approaches may be the easiest method to achieve a safe flexure mobilization. Often taking a “splenic flexure first” approach can be helpful. Especially if you know the flexure will definitely have to be taken down. Since this is often a more challenging portion of the case, saving it for the end can lead to the temptation to cut corners and perhaps omit this step in cases where the need for flexure takedown is questionable. Starting flexure takedown prior to violation of other planes may be helpful. For those that prefer a medial-to-lateral approach to the left colon, this approach can simply be extended up to the splenic flexure. The patient is initially positioned in Trendelenburg and tilted toward their right side. The mesocolon is grasped and elevated toward the anterior abdominal wall, and dissection continues in a lateral and cephalad direction. This will bring the surgeon underneath the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV), which affords one the opportunity to perform a high ligation of this vessel (Fig. 18.4). This serves to assist in gaining length on the left colon for anastomosis, it aids in ensuring an adequate lymphadenectomy, and it brings the surgeon underneath the splenic flexure itself.

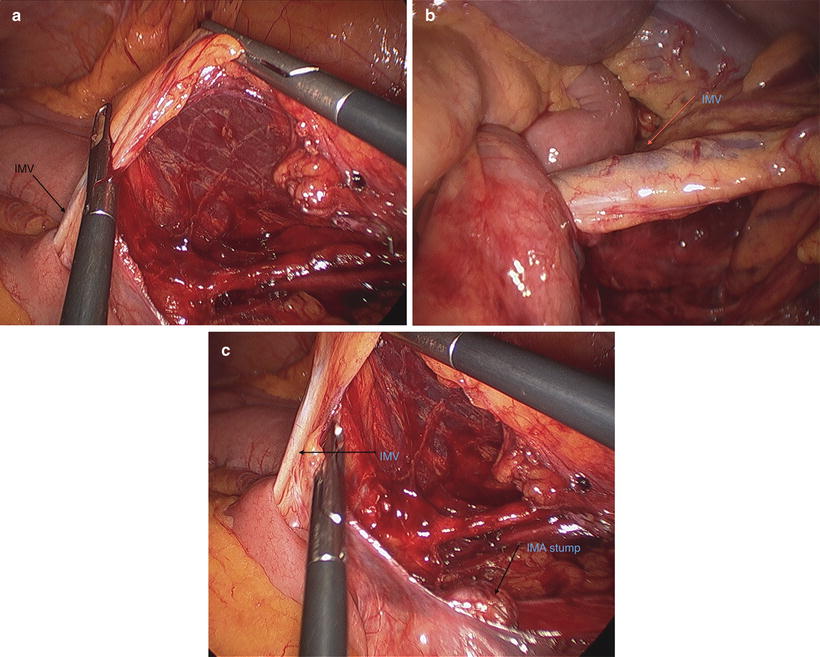

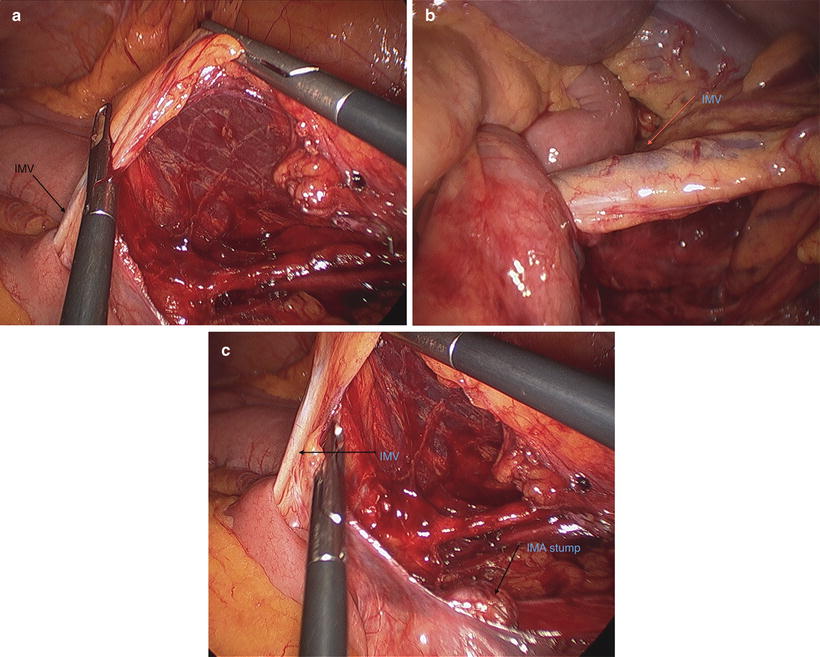

Fig. 18.4

(a, b, c) In these images the inferior mesenteric vein is shown after being approached from the medial side. The vessel is elevated and placed on gentle traction

Another option, if the medial approach is not continued, is to turn your attention to the lateral and cephalad attachments of the flexure. At this point, positioning is changed to reverse Trendelenburg, while tilt toward the patient’s right side is maintained. Because a significant amount of medial mobilization has been performed, a “darker” color (Fig. 18.5) can be seen through the lateral and cephalad attachments. These attachments can easily be divided in the proper plane and direction using the medial dissection as a guide. Because of potential vascularity in the lienocolic ligament and surrounding tissues, it is often helpful to use an advanced bipolar or ultrasonic energy device in dividing these tissues (Video 18.2).

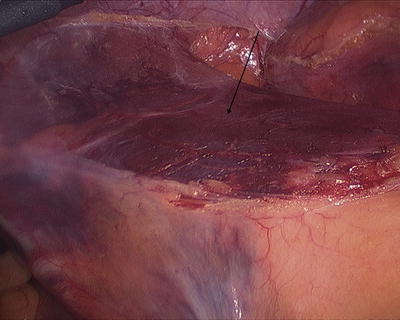

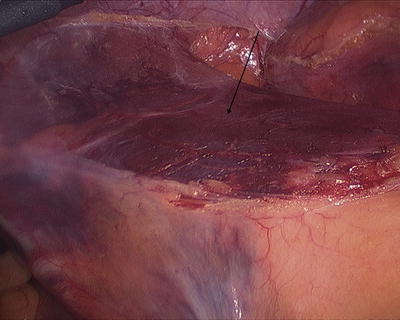

Fig. 18.5

When a previously dissected plane is encountered after being approached from another direction, the surgeon will be able to appreciate this darker appearance. It often assists in confirming that the dissection plane is correct

A third alternative is to start at the mid-transverse colon and separate the omentum from the transverse colon to enter the lesser sac. Once the lesser sac is accessed, the dissection continues out toward the splenic flexure to separate the omentum from the transverse colon and divide any adhesions of the omentum to the transverse colon mesentery in the lesser sac. All of these maneuvers increase the mobility of splenic flexure, so it is often helpful to incorporate all of them to get it mobilized safely.

Care must be exercised at the cephalad portion of the dissection when choosing the “sub-IMV” approach, as dissection in this area will be very close to the inferior border of the pancreas. It is very easy for those less familiar with this territory to find oneself underneath the tail of the pancreas, often heralded by dissection behind the splenic vein. This occurs because of the peritoneum overlying the pancreas and transverse colon mesentery on the lesser sac side. It may be difficult to visualize the pancreas, especially in an obese patient, and the structure may be injured during this dissection. If the pancreas is encountered and injury is suspected, it is wise to leave a closed-suction drain behind in the pancreatic bed. To avoid this, once the IMV is dissected, the surgeon should look “up” at the backside of the left colon and distal transverse mesocolon mesentery to identify the subtle avascular plane between the pancreas and mesocolon. Dissection in this plane will keep the pancreas down in the retroperitoneum, avoid damage and any resultant morbidity, and allow access to the lesser sac.

Complete splenic flexure mobilization requires dissection onto and mobilization of the distal transverse colon. If one encounters difficulty with the “sub-IMV” or lateral and retrograde approach to the flexure, it is often helpful to abandon these approaches and begin dissection of the transverse colon (Fig. 18.6). The omentum can be reflected cephalad over the anterior surface of the stomach. Changing position again to Trendelenburg will allow gravity to assist in maintaining cephalad positioning of the omentum. A window is then created where the omentum attaches to the transverse colon. This line of dissection can be extended toward the splenic flexure, effectively detaching the omentum from the distal transverse colon. This opens the lesser sac and allows better definition of the transverse mesocolon that can now be divided from its retroperitoneal attachments. If dissection becomes difficult, the surgeon may work back and forth between the medial, lateral, and transverse colonic approaches dissecting what seems easy until complete mobilization has been achieved. If required, hand assistance can be invaluable in mobilizing a difficult splenic flexure and can be utilized in all of the above-described techniques.

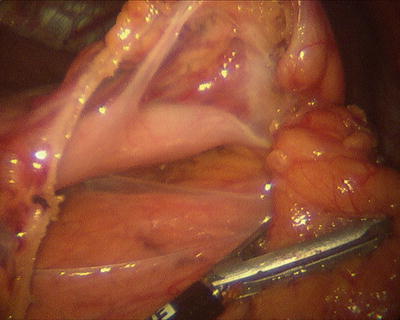

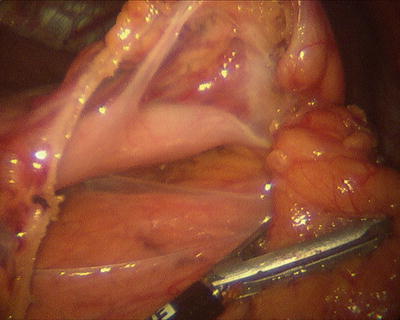

Fig. 18.6

In this image, the splenic flexure is approached along the transverse colon from a medial direction. The greater omentum has been opened along the border of the colon and the lesser sac is entered. The posterior wall of the stomach and the pancreas are clearly seen

The Transverse Colon

The transverse colon is a relatively mobile structure at its midpoint and can be quite redundant. Mobilization of the transverse colon and division of its vasculature can be one of the most challenging tasks to perform laparoscopically. In most scenarios, the transverse colon is approached after mobilization and division of the vasculature of the left or right colon as a part of an extended right or left colectomy, as a method of colonic mobilization to perform a tension-free anastomosis, or as a part of total abdominal colectomy or proctocolectomy. It is unusual to perform an isolated segmental transverse colectomy, and that will not be discussed.

From the Right

The approach to the transverse colon is typically determined by whether a left- or right-sided resection is being performed. If approaching from the right, it is wise to take down the hepatic flexure of the colon (Video 18.3) and gain access to the lesser sac by dividing the lesser omentum. This is more easily achieved on the right than the left. Because of the vascularity of these areas, it may be easiest to divide these tissues with an advanced energy device. Locating the middle colic artery can be challenging, especially in the obese patient. This can be performed from above or below the transverse mesocolon—or via a “medial-to-lateral” approach versus a classic approach. If the ileocolic artery has already been divided from a medial approach, one can simply continue this approach medially and cephalad until encountering the middle colic vessels. The middle colic can then be divided with a stapler or energy device, which will result in a highly mobile segment of transverse colon. One potential pitfall of this approach occurs when the patient has a true right colic artery arising from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), which is rare and is seen in only 10 % of individuals [3]. In this case, the right colic would be divided with the middle colic only being encountered during continued dissection across the transverse colon. While this would tend to be a necessary step in the operation anyway, it can lead to confusion about vascular anatomy and concern for division of the SMA itself. Another potential pitfall for the medial approach to the middle colic vessels is the adhesions or attachments of the omentum to the transverse colon mesentery in the lesser sac. This can make isolation and visualization of the middle colic vessels challenging. Completely opening up the lesser sac by dividing the lesser omentum or separating the omentum from the transverse colon before approaching the vasculature can be helpful. By having the lesser sac completely open, the potential for obscure bleeding or inadvertent injury to adjacent structures is minimized.

Approaching the middle colic vessels from above the transverse colon is more consistent with the classically described open procedure and is relatively simple from the right-hand side. One must take care to beware of injuring the duodenum, head of the pancreas, and gallbladder during this step. Again, once the lesser sac is entered, the transverse mesocolon can be divided by lifting it off of the retroperitoneal structures, clearly visualizing the anterior and posterior surfaces, and properly using a stapler or energy device. As a note of caution, if utilizing an energy device, take care to clearly visualize the entire extent of the vessel being divided, and apply the device completely across and perpendicular to the vessel (Video 18.4). Failure to perform these steps may result in significant delayed bleeding (Video 18.5). Because the middle colic vessels may be short with a high origin, a loss of control of these vessels can be problematic. This is a high rent district with the pancreas, stomach, duodenum, and superior mesenteric vessels all in this area, so great caution must be used to prevent and control bleeding.

From the Left

If the approach is associated with a left-sided resection, the anatomy may be a bit more challenging. The advantage here is that one may not have to deal with the middle colic vessels. Because the fusion plane between the omentum and the transverse mesocolon tends to complex near the splenic flexure, it tends to be easier to begin to develop this plane at the mid-transverse colon. As mentioned earlier, the omentum may be retracted cephalad, exposing its attachment to the transverse colon. This attachment is opened and the lesser sac is entered. If there is a desire to preserve the greater omentum, it should be detached completely from the transverse colon in this same plane. In this case, the attachment is right adjacent to the bowel wall, though there is a clear avascular area to begin dissection. If omental preservation is not a goal, then the omentum can be divided above the transverse colon using an energy device once the lesser sac is entered. This dissection can also begin above the transverse colon by opening the lesser omentum and continuing to the left. It is wise to mobilize as much of the left colon as possible prior to performing the above. If the splenic flexure can be taken down with ease, then one will already be in the proper plane to perform this dissection, and the surgeon can simply continue to progress from the patient’s left to as far medial as necessary. Often, because of difficulty with omental fusion proximal to the splenic flexure, this area is approached from both sides until it is completely freed from surrounding tissues.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree