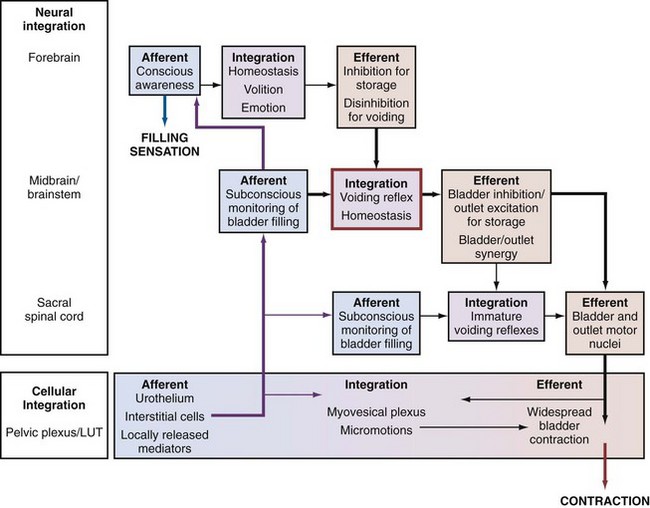

Marcus Drake, DM, MA, FRCS (Urol), Paul Abrams, MD The overactive bladder (OAB) is a prevalent problem, with considerable effects on the quality of life of affected individuals and substantial health economic costs. The condition is symptom based and defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) standardization committee as urgency, with or without urgency incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia, if there is no proven infection or other obvious pathology (Abrams et al, 2002). A correction had to be put forward when it was realized that the term “urge incontinence” had been used in the original definition (Abrams et al, 2009). OAB is thus a syndrome in which several of the lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) relating to the storage of urine coexist, with urinary urgency as the essential parameter. Because urgency will frequently arise at comparatively small bladder volumes, patients tend to describe frequent voids with a low typical voided volume. Nocturia as a symptom is somewhat variable in OAB because the supine position and reduced physical exertion overnight seem to be less provocative in eliciting OAB. A difficulty with the ICS definition is that some patients may void preemptively (defensive voiding), passing urine before urgency arises; they will thus clearly have storage-phase LUTS yet lack the urgency symptom, which is the defining characteristic of OAB. In many OAB patients, urgency incontinence occurs, defined as involuntary leakage of urine, accompanied or immediately preceded by urgency (Abrams et al, 2002). This standardized definition abandoned the requirement that the leakage should be a “social or hygienic problem” to be called incontinence because considerable leakage can occur, which in some individuals may not be a problem to them, particularly in children and the elderly. In a prevalence survey, 69% of women had “any incontinence,” but only 30% found this a “social or hygienic problem” (Swithinbank et al, 1999). Before the introduction of the standardized definitions, the use of several overlapping terms resulted in a confusing situation, hampering many aspects of research and management. The English-speaking world had adopted Patrick Bates’ term unstable bladder to describe involuntary detrusor contractions seen during urodynamic studies as the bladder was filled, while the Scandinavians used the term detrusor hyperreflexia. To resolve the discrepancy, the ICS designated the term unstable bladder to be applied where there was no obvious cause for the contractions and detrusor hyperreflexia for patients whose involuntary contractions had a neurologic cause (Bates et al, 1980); overactive detrusor was used as the generic, overarching term. Nonetheless, the use of different terms in neurologic and non-neurologic patient groups became increasingly difficult. Firstly, several studies showed considerable overlap in the underlying mechanisms. In addition, explaining the terms to the patients and the wider medical profession highlighted the incongruity of the differing terminology. Furthermore, physicians had to be careful not to insult the sensibilities of the patient by inadvertently implying mental instability by using the word “unstable” in relation to bladder symptoms. “Overactive Bladder” was used as the title of a consensus conference, and a formal definition was proposed in 1999 (Abrams and Wein, 1999), culminating in the ICS definition used currently. Crucially, the current definition of OAB is based on symptoms; in contrast, detrusor overactivity (DO) is a urodynamic observation, characterized by involuntary detrusor contractions during the filling phase, which may be spontaneous or provoked (Abrams et al, 2002). OAB and DO are thus not interchangeable terms, and the clinician must be specific in their use. Clinicians need to be clear on this among themselves and when discussing urgency with patients. All measures, for example “warning time” (between first sensation of urgency and eventual voiding), depend on the patients and the clinicians reaching a consensus as to the meaning of urgency. The ICS terminology committee excluded “for fear of leakage” in the new definition of urgency, mainly because many OAB patients do not leak. Perhaps this was not entirely logical because patients can certainly feel as if they are going to leak, even if they have never actually done so. A couple of phrases are often used by patients: Hence “fear of leakage” is an important concept to patients. Key Points: OAB Terminology Until recently, insight into the pathophysiologic basis of DO has generally focused on cellular mechanisms by which unregulated motor activity could arise. The neurogenic hypothesis states that DO arises from generalized, nerve-mediated excitation of the detrusor muscle (de Groat, 1997). There are several interdependent mechanisms by which this may arise. First, damage to the brain can induce DO by reducing suprapontine inhibition. Second, damage to axonal pathways in the spinal cord allows the expression of primitive spinal bladder reflexes. Third, synaptic plasticity leads to reorganization of sacral activity, with the emergence of new reflexes, which may be triggered by C-fiber bladder afferent neurons. Finally, sensitization of peripheral afferent terminals in the bladder can trigger DO. The myogenic hypothesis suggests that overactive detrusor contractions result from a combination of an increased likelihood of spontaneous excitation within smooth muscle of the bladder and enhanced propagation of this activity to affect an excessive proportion of the bladder wall (Brading and Turner, 1994; Brading, 1997). Patchy denervation is a common observation in DO, regardless of etiology (German et al, 1995; Charlton et al, 1999; Drake et al, 2000; Mills et al, 2000). A smooth muscle cell deprived of its innervation shows an upregulation of surface membrane receptors and may have altered membrane potential, which increases the likelihood of spontaneous contraction in that cell. DO is also associated with characteristic changes in ultrastructure (Elbadawi et al, 1993; Haferkamp et al, 2003a, 2003b), which could facilitate the propagation of the contraction over a wider proportion of the body of the detrusor than normal. However, the observations in different models of DO and from clinical specimens do not uniformly describe these features. The afferent nerve endings are widely distributed in the bladder wall and are particularly dense in the connective tissue underneath the urothelium. In this location, they may be influenced by several cell types. Urothelial cells possess sensory and signaling properties that allow them to respond to their chemical and physical environments and to communicate with subjacent structures (Birder, 2001). Suburothelial interstitial cells lie in close physical proximity to nerve fibers, suggesting a role in sensory transduction or regulation (Wiseman et al, 2003). The number of impulses fired by an afferent ending at any level of distention can be varied physiologically; that is, the gain of the sensory nerve endings can be changed to vary the “afferent sensitivity.” Thus the rate of firing in a particular afferent normally associated with a high vesical volume can occur at lower volumes if the afferent ending has been sensitized. Accordingly, the release of substances from the urothelium, as well as the direct interaction between afferent nerve endings and other cell types, may physiologically influence central reporting of the bladder state and could well contribute pathophysiologically. In theory, OAB may arise if the level of sensory activity is inappropriately high for any given degree of bladder distention, resulting from pathologically sensitized or abnormally numerous afferent nerve endings. The interaction among afferents, urothelium, and interstitial cells is thus interesting, in that modulating their interactions may result in amelioration of symptom severity. The expression of various receptors on urothelium and afferents, particularly members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family, may thus be relevant in the development of future clinical management options. The sensory information is carried to the spinal cord by myelinated Aδ fibers and unmyelinated C fibers. As a general rule, the Aδ fibers are regarded as responding to passive bladder distention and active detrusor contraction (“in series” mechanoreceptors [Iggo, 1955]), thus conveying information about bladder filling (Janig and Morrison, 1986). C fibers are regarded as responding primarily to chemical irritation of the bladder mucosa (Habler et al, 1990) or to thermal stimulus (Fall et al, 1990). Accordingly, they may be less active in the physiologic state than the Aδ fibers. Nonetheless, there is almost certainly considerable overlap in the sensory information carried by the two types of afferent, and the C fibers may take on a more prominent role in the pathologic state. The afferent, neurogenic, and myogenic mechanisms alluded to earlier are essentially based on physiology of individual cell types. However, the complexity of lower urinary tract function is substantially increased by the potential interactions between differing cell types and their humoral/paracrine environments. The integrative properties determining the interaction between cell types is manifest in the neural circuits of the central nervous system, as well as the periphery (Fig. 66–1)—the latter working through networks (neural, interstitial cells) and by direct cell communication in the urothelium or muscle cell–to–muscle cell. The presence of interstitial cells in the bladder led to the proposal of a regulatory “myovesical plexus” comprising nerves (excitatory and inhibitory, peripheral and central) and interstitial cells loosely, akin to gut myenteric plexuses. The integrative hypothesis of OAB draws on the various contributory factors to understand the normal micturition cycle, OAB, and DO (Drake et al, 2001). Several observations can be understood by focusing on activity within the bladder wall itself: The crucial factors in the integrative hypothesis are the level of excitation and degree of propagation in the myovesical plexus structures of the bladder wall. Both will be at low levels during normal bladder filling. Local excitability is high in OAB, whereas propagation alone is high in asymptomatic DO; both are increased where DO is symptomatic. Propagation is high in normal voiding (driven by efferent commands from the central nervous system [CNS]). Increased local excitation with impaired propagation could explain why patients have OAB and a PVR (detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (Resnick and Yalla, 1987). The development of functional brain imaging technology allows estimation of gross activity in specific brain areas and has been used to study bladder filling in normal and symptomatic individuals. Intriguing insights into contributions from various parts of the cerebral cortex such as the insula and the prefrontal cortex have resulted. Alterations in the regional brain activity of symptomatic individuals with OAB have been reported (Griffiths et al, 2007). Understanding brain responses to lower urinary tract activity through autonomic afferent processing networks, as is already under investigation for the gastrointestinal tract, will be crucial in the endeavor to develop improved clinical management options. Key Points: OAB Pathophysiology Using the standardized ICS definition of OAB, the EPIC study reported the prevalence of OAB in four European countries and in Canada, reporting an overall OAB prevalence of 11.8%, in the context of a prevalence of 64.3% for at least one LUTS (Irwin et al, 2006). The EPIC study also catalogued multidimensional impact including effects on employment (Coyne et al, 2008; Irwin et al, 2009). Older studies have to be interpreted according to the definitions they used for LUTS. One prevalence study (Milsom et al, 2001) reported prevalence of OAB symptoms that “occurred singly or in combination,” estimating overall OAB prevalence at 16%. In the studied population, 9.2% had urgency, and this is perhaps closer to the true prevalence of OAB in the community. The NOBLE study (Stewart et al, 2003) established the prevalence of OAB in more than 5000 community-dwelling individuals in the United States using a validated computer-assisted telephone interview. Men and women had the same prevalence of OAB overall (16.0% and 16.9%, respectively) as defined by the ICS. However, men were shown to have a higher prevalence of “OAB dry” (13.4% as opposed to 7.6% in women) and women had a higher prevalence of “OAB wet” (9.3% as opposed to 2.6% in men). It is assumed that the difference in the prevalence of incontinence is due to the relative weakness of the bladder neck and urethral sphincter mechanism in women, particularly in those who have had children. In women the prevalence of “OAB wet” rose from 2.0% in the youngest group (ages 18 to 24) to 19.1% in those 65 to 74 years of age. Men, on the other hand, did not experience an increase in “OAB wet” until older: 8.22% for those 65 to 74 and 10.2% for those 75 years and older.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Hypotheses of Detrusor Overactivity

Afferent Mechanisms in Overactive Bladder and Detrusor Overactivity

Integrative Physiology of Overactive Bladder

Central Nervous System

Etiology

Prevalence

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Overactive Bladder

• The International Continence Society updated its definitions for OAB and other lower urinary tract dysfunctions in 2002.

1. Generation of normal and increased filling sensations in the absence of pressure change; the sensations of normal desire and strong desire to void arise in the absence of change in detrusor pressure. This could arise as a consequence of localized contractions (Drake et al, 2001), which are active in only a small part of the bladder wall, so they do not measurably affect intravesical pressure but result in small distortions that are detected by the afferent nerves. Such activity, termed “micromotions,” is seen in various animal models and humans (Van Os-Bossagh et al, 2001; Drake et al, 2003a, 2003b; Gillespie et al, 2003; Drake et al, 2005). Exaggerated micromotions would then increase filling sensations pathologically, again without affecting pressure (i.e., OAB without DO). Local mediator release in inflammatory situations such as cystitis could cause temporary urgency sensations by increasing localized contractions.

3. Completeness of bladder emptying; complete bladder emptying relies on sustaining detrusor contraction for a sufficient duration, and this could result from the myovesical plexus driving detrusor contraction during voiding (Drake, 2007). The hypothetical existence of feedback from bladder afferents into the myovesical plexus could ensure contraction is sustained for sufficient duration, and a lesion impairing this feedback would result in a postvoid residual (PVR).

• Normal lower urinary tract function derives from a complex interplay of cellular physiology and hierarchical neural control.