Outcomes Assessment

Brian S. Yamada

Kathleen C. Kobashi

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic floor disorders include a wide range of interrelated clinical conditions, such as urinary incontinence, voiding dysfunction, pelvic organ prolapse, defecatory dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction. While pelvic floor disorders seldom lead to severe morbidity or mortality, their primary impact is on quality of life. Consequently, quality of life assessment is critical when evaluating treatments for urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse (1). Traditional means of assessing efficacy of treatments for pelvic floor disorders include objective measures such as urodynamic studies, pad tests, clinical examinations, and voiding diaries. While objective measures are typically a part of the treatment assessment, clinical and research questionnaire tools are now playing a more prominent role in outcomes assessment.

When reviewing the literature for urinary incontinence and pelvic floor disorders, it is apparent that the overall quality of the body of literature is suboptimal. Even today, many practice guidelines are based on studies using objective measures alone. More recent literature suggests that objective measures are often poorly correlated to patient goals and quality of life (2). This is further complicated by the fact that much of the literature has inadequate follow-up, lack of standard definitions for the success or failure of treatments, lack of sufficient power, and a paucity or underreporting of complications.

Multiple questionnaires have been developed over the past decade and are beginning to encompass the various components associated with pelvic floor disorders. Currently, no standard questionnaire for pelvic floor disorders exists. The goal of this chapter is to give an overview of the tools currently available to the clinical and research urologist and urogynecologist. Most of the available instruments focus on only one component of the multifaceted pelvic floor, but recently questionnaires have begun to include symptoms reflective of the multiple compartments, with specific items designed to address quality of life.

QUESTIONNAIRE DEVELOPMENT

Although a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, a brief summary of the steps necessary for developing a questionnaire is provided. The initial focus in questionnaire development is the compilation of pertinent items via evaluation of existing scales and the addition of questions based on input from “experts” in the field and discussion with patients. A new questionnaire is assessed for content validity to see whether it appears to cover all the relevant or important domains. The questions are then assessed for face validity, which determines that the items actually measure what they are intended to measure. Validity testing also involves testing the criteria against a gold standard, if one exists (3).

Next, reliability testing is performed to ensure that the items in a questionnaire are measured in a reproducible fashion. Reliability is usually quoted as a ratio of the variability between individuals to the total variability in the scores. It is expressed as a number between 0 and 1, with 0 indicating no reliability and 1 indicating perfect reliability (3). Reliability testing includes intraobserver reliability, interobserver reliability, and test-retest reliability. Intraobserver reliability assesses the consistency between observations made by the same rater on two different occasions. Interobserver reliability assesses the degree of agreement between different observers. Test-retest reliability assesses the consistency of responses on a given item separated by an interval of time to evaluate whether the item would be interpreted and answered the same way twice by the same individual (3).

Internal consistency further confirms reliability and refers to the degree of correlation between the

questionnaire items. Items forming a domain should moderately correlate with each other but also contribute independently to the overall domain score (4). These correlations are calculated using Cronbach’s alpha and should exceed a value of 0.8. Responsiveness is the ability of an instrument to detect a small but clinically important change. This psychometric property is often neglected in the literature (5,6).

questionnaire items. Items forming a domain should moderately correlate with each other but also contribute independently to the overall domain score (4). These correlations are calculated using Cronbach’s alpha and should exceed a value of 0.8. Responsiveness is the ability of an instrument to detect a small but clinically important change. This psychometric property is often neglected in the literature (5,6).

Finally, the questionnaire must have adequate interpretability, meaning that ambiguous or incomprehensible items should be eliminated. The method of questionnaire administration may also affect participant responses. For example, a better correlation to urodynamic findings was found in patients who were administered the Bristol Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms questionnaire in the mailed self-administered form versus inter-view-assisted administration (7).

This chapter contains descriptions of numerous questionnaires available for evaluation of symptoms and quality of life pertaining to urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse, and sexual dysfunction. Each of the questionnaires to be discussed underwent a thorough validation process. Some of the described instruments have been updated with short-form versions. Short-form questionnaires are potentially useful when an instrument is frequently used or the assessment time is limited. Long questionnaires are time-consuming and may increase the number of unanswered items (8).

TRADITIONAL OUTCOMES MEASURES: URODYNAMICS, PAD TESTS, BADEN-WALKER, PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE QUANTIFICATION (POP-Q)

Two traditional outcomes measures used to measure success of therapy for stress urinary incontinence include urodynamics and the 1-hour pad test. These tests, however, do not necessarily correlate well to questionnaire results. For example, urodynamics has not been proven to be accurate in detecting the presence or severity of incontinence unless the bladder volume is fixed at 200 to 300 cc or 50% to 75% of bladder capacity. These measures do not assess quality of life and therefore provide an incomplete picture of patient status.

Pelvic organ prolapse is assessed in part by physical examination. Physical examination has also traditionally been used to determine the success of prolapse repair. The two standard systems for assessing prolapse are the Baden-Walker system and the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) system. The International Continence Society recognizes the POP-Q as the standard measurement system. While useful as part of patient assessment, it is controversial whether these measures correlate to clinical symptoms and quality of life. Further description of the POP-Q exam as it pertains to symptoms is presented later in this chapter.

CURRENT INSTRUMENTS: URINARY INCONTINENCE AND PELVIC PROLAPSE

Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ)

The Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) was developed by Shumaker in 1994 with the goal of assessing the degree to which symptoms associated with urinary incontinence are bothersome. The original UDI has 19 questions and encompasses three domains (symptoms related to stress urinary incontinence, detrusor overactivity, and bladder outlet obstruction). The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) was developed at the same time and assesses the impact of urinary incontinence on activities, social roles, and emotional states in women (9). It consists of 30 questions and covers four domains (physical activity, social relationships, travel, and emotional health). Each question has a 4-point response scale (0 = not at all, 1 = slightly, 2 = moderately, 3 = greatly). Both the UDI and IIQ were developed for simple self-administration. Both questionnaires are strong psychometrically and numerous authors have supported their validity (10,11). Neither questionnaire specifically addresses pelvic prolapse or its associated symptoms.

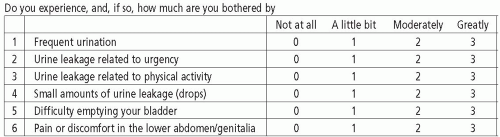

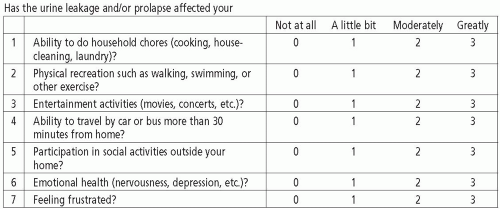

In 1995, short-form versions of the UDI and IIQ were created (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2). The 19-item UDI was condensed into a 6-item questionnaire and named the UDI-6. The 30-item IIQ was condensed into the 7-item IIQ-7. Regression analysis of each short form suggested that they would accurately predict the results of the long form. Both questionnaires were validated and are considered to be more useful than their long forms in many clinical and research applications (12). The UDI-6 has been shown to correspond to findings on urodynamics. Lemack et al demonstrated that most patients reporting moderately or greatly bothersome stress incontinence on the UDI-6 were found to have stress leakage on urodynamics, which differed significantly from those who reported no bother. Valsalva leak point pressure did not correlate to symptom severity on the scale. Urgency symptoms described as moderately or greatly bothersome were found to have a significantly

greater incidence of detrusor overactivity on urodynamics compared to women who did not have this complaint (13).

greater incidence of detrusor overactivity on urodynamics compared to women who did not have this complaint (13).

Other authors have suggested certain limitations of the IIQ and UDI. Handa found that most items in the IIQ were useful for discriminating incontinence among women with mild-to-moderate urinary incontinence but tended to underestimate the magnitude of changes of incontinence severity in women with severe urinary incontinence (11). Harvey found that the IIQ and UDI appeared to be valid in women with a urodynamic diagnosis of incontinence but were of questionable validity as markers of incontinence severity in women without a urodynamic diagnosis (14).

International Consultation on Incontinence (ICIQ) Modular Questionnaire

Sponsored by the World Health Organization and organized by the International Continence Society and the International Consultation on Urological Diseases, the first International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) was held in 1998. This committee supported the idea that a universally applicable questionnaire should be developed for urinary incontinence (15). The goal was that such a questionnaire could be widely applied both in clinical practice and research, used in different settings and studies, and allow for cross-comparisons. For example, the questionnaire could cross-compare a drug treatment to an operation used for the same condition, in the same way that that the International Prostate Symptoms Score (IPSS) has been used (15). The end result was the development of the ICIQ Modular Questionnaire.

The first module developed was the ICIQ-UI Short Form for urinary incontinence, which has been validated and published (16). Other modules have been added to the ICIQ Modular Questionnaire by the adoption and renaming of several pre-existing, validated scales (17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22). The adopted questionnaires pertaining to female pelvic floor disorders are listed in Figure 3.3. Additional modules are being developed for urinary tract, vaginal, and lower bowel symptoms. Each of these modules deal with quality of life and sexual function in a

condition-specific manner. A website (www.iciq. net) has been created to make these instruments easily accessible (15).

condition-specific manner. A website (www.iciq. net) has been created to make these instruments easily accessible (15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree