Richard J. Glassock

Other Glomerular Disorders and the Antiphospholipid Syndrome

This chapter provides a description of several glomerular and vascular diseases, not necessarily related to each other. Each disorder must be recognized and differentiated from other, more common glomerular disorders to estimate the prognosis, to determine whether a familial disorder is present, to plan appropriate therapy, or to determine the risk of a recurrence in the transplanted kidney.

Mesangial Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Without IgA Deposits

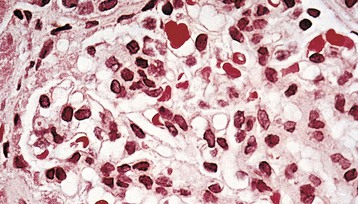

Mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (MesPGN) encompasses a heterogeneous collection of disorders having a diverse and largely unknown etiology and pathogenesis. The common feature that binds these various disorders is a histologic pattern on light microscopy of glomerular injury characterized by diffuse mesangial proliferation1–3 (Fig. 28-1). Thus, MesPGN is noted for a diffuse and global increase in mesangial cells, often accompanied by an increase in mesangial matrix. Other cells (e.g., monocytes) may also contribute to the hypercellularity. As such, MesPGN is a glomerular lesion, not a specific disease entity.

For the purpose of this discussion, other forms of cellular proliferation that occur within the mesangial zones but are more focally and segmentally distributed are not included. These focal and segmental forms of proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN), often accompanied by areas of segmental necrosis of the glomerular tufts and very localized crescents, may be a part of the evolutionary stages of an initially pure MesPGN, but they often signify the presence of systemic disease processes, including systemic lupus, Henoch-Schönlein purpura and IgA nephropathy, infective endocarditis, microscopic polyangiitis, granulomatous polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis), Goodpasture disease, rheumatoid vasculitis, and mixed connective tissue disease. On occasion, a lesion of focal and segmental proliferative GN is discovered in the absence of any recognizable multisystem disease process and in the absence of IgA deposits (i.e., idiopathic focal and segmental proliferative GN). Such patients have a clinical presentation, course, and response to treatment that are similar to those described for pure MesPGN, but they are not discussed further in this section.

In “pure” MesPGN, the peripheral capillary walls are thin and delicate without obvious deposits, reduplication, focal disruptions, or cellular necrosis. The visceral and parietal epithelial cells, although occasionally enlarged, have not undergone proliferation. Crescents and segmental sclerosis should be absent in the “pure” form of the disorder. In addition, large deposits staining with periodic acid–Schiff or fuchsin in the mesangium should be absent, because these deposits suggest IgA nephropathy (see Chapter 23) or lupus nephritis (see Chapter 26). The tubulointerstitium and vasculature are usually normal, unless reduced renal function or hypertension is present or the patient is of advanced age.

On immunofluorescence (IF) microscopy, a wide variety of patterns of immunoglobulin and complement deposition are observed (Table 28-1). Most often, diffuse and global IgM and C3 deposits are found scattered throughout the mesangium in a granular pattern (so-called IgM nephropathy), but isolated C3, C1q, or even IgG deposits may also be seen.4 If IgA is the predominant immunoglobulin deposited, the diagnosis is IgA nephropathy. In some cases, no immunoglobulin deposits are found at all. Prominent C3 deposition in the absence of immunoglobulin deposition should suggest a C3 glomerulopathy (see Chapter 22).5 Extensive C1q deposits, with or without immunoglobulin deposits should suggest C1q nephropathy.6

Table 28-1

Immunofluorescence microscopy patterns in mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis (MesPGN).

| Immunofluorescence Microscopy Patterns in MesPGN | |

| Pattern | Associated Disorders |

| Predominantly mesangial IgA deposits | IgA nephropathy (± IgM, C3) |

| Predominantly mesangial IgG deposits | Often associated with systemic lupus (± IgM, C3) |

| Predominantly mesangial IgM deposits | IgM nephropathy (± C3) |

| Mesangial C1q deposits | C1q nephropathy (± IgG, IgM, C3) |

| Isolated mesangial C3 deposits | Often associated with resolving poststreptococcal GN |

| Negative for immunoglobulin or complement deposits | Idiopathic MesPGN |

On electron microscopy (EM), the number of mesangial cells is increased, with an occasional infiltrating monocyte or polymorphonuclear leukocyte. The amount of mesangial matrix is frequently but not invariably diffusely increased. Electron-dense deposits within the mesangium can be seen in many cases, particularly those with immunoglobulin (IgG or IgM) deposits on IF microscopy. Very large mesangial or paramesangial electron-dense deposits suggest IgA nephropathy even if IF microscopy is not available. Subendothelial, intramembranous, or subepithelial deposits are not seen. If present, these suggest a postinfectious etiology such as underlying lupus nephritis or a C3 glomerulopathy. Deposits of multiple immunoglobulin classes identified by immunohistology and large numbers of tubuloreticular inclusions on EM suggest underlying lupus nephritis.

The clinical presentation of MesPGN is quite varied, although persistent or recurring microscopic or macroscopic hematuria with mild proteinuria is most common. Nephrotic syndrome with heavy proteinuria is a less frequent initial presentation but is seen more often in association with diffuse mesangial IgM deposits (IgM nephropathy)2 or C1q deposits (C1q nephropathy).4,6 Pure MesPGN is a rather uncommon lesion (<5%) in patients diagnosed with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome.2,3 Lesions of MesPGN have been observed in acute parvovirus B19 disease and in association with Castleman disease.7,8

Renal function and blood pressure are usually normal, at least initially. Serologic studies are generally unrewarding. Serum C3 and C4 complement components and hemolytic complement activity (CH50) are normal. A low C3 level suggests a C3 glomerulopathy. Assay results for antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA), anti–glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) autoantibody, and cryoimmunoglobulins are negative. Nevertheless, these studies should be performed in most patients to exclude known causes. MesPGN can also be a finding in resolving postinfectious (poststreptococcal) GN. Isolated C3 deposits with scanty, subendothelial or subepithelial (hump-like) deposits on EM may be seen in this situation. Urinary protein biomarkers may help to determine prognosis.9

IgM Nephropathy

IgM nephropathy2 is characterized by diffuse and generalized glomerular deposits of IgM often accompanied by C3. Mesangial electron-dense deposits are also observed. On light microscopy, a picture of “pure” MesPGN is usually observed, sometimes with superimposed focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).10 It is an uncommon finding accounting for <5% of all renal biopsies.10 Patients may present with recurring macroscopic hematuria and proteinuria, the latter in the nephrotic range in as many as 50% of patients. Persisting abnormalities and a poor response to corticosteroids or immunosuppressive therapy are often seen. As many as 50% of patients will eventually progress to typical FSGS and, if unresponsive to corticosteroids, will slowly develop chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Treatment of IgM nephropathy is highly uncertain, although steroid therapy may be associated with a complete or partial remission in as many as 50% of patients. The etiology and pathogenesis are unknown.

C1q Nephropathy

C1q nephropathy is characterized by diffuse deposits of C1q, often accompanied by IgG, IgM, or both.4,6 C3 deposits are observed less frequently. These immunopathologic features resemble those seen in lupus nephritis; however, these patients have none of the clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and do not develop SLE even after prolonged follow-up.11 In addition to MesPGN, other morphologic lesions, including FSGS, are typically observed by light microscopy. Nephrotic-range proteinuria occurs, often with hematuria. Males predominate, and African Americans are often affected. Serum C3 components, ANA, and anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibodies are consistently normal or negative. The response to treatment is poor, and progression to ESRD may occur.

Mesangial Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Associated with Minimal Change Disease

MesPGN may also be a part of the spectrum of minimal change disease (MCD)–FSGS lesions (see also Chapters 17 to 19). Distinct mesangial hypercellularity superimposed on a lesion of MCD (diffuse foot process effacement seen on EM) may point to a greater likelihood for corticosteroid unresponsiveness and an eventual evolution to the FSGS lesion.

Natural History of Mesangial Proliferative Glomerulonephritis

The natural history of MesPGN varies, undoubtedly the result of etiologic and pathogenetic heterogeneity. In many patients, a benign course ensues, especially if hematuria and scant proteinuria (<1 g/day) are the principal features. Persisting nephrotic syndrome has a less favorable prognosis, and such patients may evolve into FSGS (see Chapters 18 and 19) and accompanying progressive CKD.3,10

Treatment of Mesangial Proliferative Glomerulonephritis

The treatment of “pure” MesPGN, unaccompanied by other underlying diseases or lesions such as SLE, C1q nephropathy, IgM nephropathy, MCD lesion, or IgA nephropathy, has not been well defined.2,3 No prospective, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been performed because of the uncommon nature of the disorder. The prognosis for patients with isolated hematuria or hematuria combined with mild proteinuria (<500 mg/day) is generally benign, and thus no treatment other than management of hypertension is needed. For those patients with nephrotic syndrome, with or without impaired renal function, a more aggressive approach is often recommended, especially in the presence of diffuse IgM deposits, as discussed earlier, because many such patients will eventually progress to FSGS. Even in the absence of RCTs, an initial course of corticosteroid therapy may be justified in most patients with nephrotic-range proteinuria, such as prednisone, 60 mg/day or 120 mg every other day for 2 to 3 months, followed by lowered doses on alternate-day regimen for 2 to 3 additional months. About 50% of these patients experience a decrease in proteinuria to subnephrotic levels. Complete remissions occasionally occur. However, relapses of proteinuria are common when steroids are tapered or discontinued. Such relapsing, partially corticosteroid-responsive patients might benefit from the addition of cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, or even cyclosporine or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) to the regimen, although information on the therapeutic efficacy and safety of these agents in pure MesPGN is very limited.

Patients with persistent treatment-unresponsive nephrotic syndrome will almost invariably progress to ESRD over several years. Whereas transplantation is not contraindicated, patients who do progress to ESRD rapidly and who develop superimposed FSGS may have a high risk of recurrence of proteinuria and FSGS in the transplanted kidney.

Glomerulonephritis with Rheumatic Disease

Several so-called collagen vascular diseases other than SLE may be complicated by GN (Box 28-1). This section covers the glomerulonephritides that accompany rheumatoid arthritis,11 mixed connective tissue disease,12 polymyositis and dermatomyositis, acute rheumatic fever, scleroderma, and relapsing polychondritis. IgA nephropathy may also be seen in association with the seronegative spondyloarthropathies.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

A wide variety of glomerular, tubulointerstitial, and vascular lesions of the kidney may complicate rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Box 28-2). Clinical abnormalities, including abnormal urinalyses (hematuria, leukocyturia, proteinuria), and reduced renal function are common in patients with RA, particularly those with severe or longstanding disease. Membranous nephropathy (MN) (see Chapter 20) is the most common glomerular lesion encountered, possibly because of the underlying disease itself or its therapy (parenteral or oral gold or penicillamine). The presence of HLA-DR3 increases the risk for development of MN in a patient with RA. The lesion is not associated with anti–phospholipase A2 receptor (anti-PLA2R) autoantibodies.

The course of MN in association with RA, in the absence of drugs, is similar to that of the idiopathic disease, although spontaneous remissions appear less likely to occur. By comparison, MN associated with drugs used to treat RA is most likely to remit after discontinuance of the drug therapy.11 Such remissions may take many months to occur. Nevertheless, 60% to 80% of RA patients with drug-induced MN will remit within 1 year of stopping treatment.

Secondary (AA) amyloidosis (see Chapter 27) is found in 5% to 20% of patients with RA undergoing renal biopsy. Nephrotic syndrome and progressive renal failure are common.

The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may also produce tubulointerstitial nephritis or MCD (see also Chapters 60 and 17).13A severe, necrotizing polyangiitis may complicate the course of longstanding RA (rheumatoid vasculitis).14 These patients may have profound reduction in C3 levels, striking elevation of rheumatoid factors, and marked polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. Renal involvement in rheumatoid vasculitis is now relatively uncommon for poorly understood reasons. The use of TNF-α inhibitors for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis can evoke a picture resembling lupus nephritis (see Chapter 26).

Mixed Connective Tissue Disease

Mixed connective tissue disease is characterized by features that overlap with those of SLE, scleroderma, and polymyositis.12 Typically, the serum of such patients contains high-titer autoantibodies to extractable nuclear antigens (ribonucleoprotein-extractable nuclear antigen, U1 ribonucleoprotein antigen). Low titers of anti-dsDNA antibody may also be found. Renal disease, originally thought to be quite rare, is found in 10% to 50% of patients, most frequently MN and MesPGN.14 Treatment with steroids is generally effective, but some patients exhibit progressive CKD. Patients with severe GN may respond to treatment regimens similar to those used in the treatment of lupus nephritis (see Chapter 26).

Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

The related collagen vascular diseases polymyositis and dermatomyositis are characterized by inflammatory lesions in muscle and variable skin lesions and often include Raynaud phenomenon.15 On occasion, patients have proteinuria and hematuria secondary to MesPGN with IgM deposits. Acute kidney injury (AKI) may rarely supervene when severe muscle injury and myoglobinuria are present. Treatment with steroids may, at least in part, ameliorate the renal manifestations in concert with improvement in the muscle and skin manifestations.

Acute Rheumatic Fever

Acute rheumatic fever secondary to a pharyngeal (but not cutaneous) infection with a rheumatogenic strain of group A β-hemolytic streptococci is seldom accompanied by renal disease16 (see Chapter 57). Poststreptococcal GN and acute rheumatic fever almost never coexist because of the distinct difference between nephritogenic and rheumatogenic strains of streptococci. In addition, cutaneous streptococcal infections are never associated with acute rheumatic fever sequelae. Nevertheless, on rare occasions, MesPGN has been associated with acute rheumatic fever.16 MesPGN usually manifests with hematuria with scant proteinuria and often resolves with appropriate treatment and control of acute rheumatic fever.

Ankylosing Spondylitis and Reiter Syndrome (Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies)

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies and oligoarticular arthropathies may be associated with mesangial IgA deposition or MesPGN in some patients. Clinical manifestations are usually mild and nonprogressive. AA amyloidosis may complicate longstanding ankylosing spondylitis.

Scleroderma (Systemic Sclerosis)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree