PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Patients with gastrinomas typically have nonspecific symptoms, and this has historically led to delayed diagnosis from 3 to 9 years after initial onset of symptoms. Although presentation may occur anytime from childhood to old age, patients typically present with a male predominance (3:2) in the fifth decade of life with sporadic gastrinomas and in the fourth decade of life with MEN-1–related gastrinomas.1

■ The most common symptoms are abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (Table 2). Typically, patients have a small, solitary ulcer (<1 cm in diameter) in the first portion of the duodenum, although they may also have a history of recurrent ulcers in atypical locations such as the jejunum (11%) and distal duodenum (14%).2,3

■ The most common complications are due to ulcer perforation, although up to 20% of patients do not have an ulcer on presentation.

■ Gastrinomas arise sporadically in a majority of cases (75% to 80%), whereas the remainder are due to MEN-1. It is important to differentiate the etiology as this dictates the clinical and surgical management of these patients. In addition to gastrinomas, patients with MEN-1 also develop parathyroid adenomas, pituitary adenomas, and other neuroendocrine tumors.4

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ If a gastrinoma is suspected, then a serum fasting gastrin level should be obtained. Prior to this test, the patient should be instructed to hold antacid medication (proton pump inhibitors held for 7 days; histamine receptor blockers held for at least 30 hours).

■ An elevated gastrin level greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal (>1,000 pg/mL) should be followed by a gastric pH probe in order to rule out achlorhydria. A gastric pH of 4.0 or greater confirms the diagnosis of gastrinoma if other etiologies (e.g., retained antrum after Billroth II resection) have been ruled out.

■ A gastrin level that is elevated but less than 10 times the upper limit of normal should be followed by a secretin stimulation test. Although normal G cell gastrin secretion is inhibited by secretin, gastrin release by gastrinoma cells is actually increased. Secretin is infused intravenously over 1 minute after baseline gastrin measurements are obtained; gastrin is then measured at 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 minutes after infusion. A positive test, typically defined by a rise in serum gastrin of 200 pg/mL or greater, confirms diagnosis of gastrinoma.

■ If these tests do not confirm the diagnosis but a high clinical suspicion remains, then additional tests may be used. The calcium infusion study consists of a continuous intravenous infusion of 5 mg/kg 10% calcium gluconate over a 3-hour period. Serum gastrin and calcium are measured prior at baseline and at 30-minute intervals for 3 hours after the test begins.5 A positive result is typically defined as an elevation in serum gastrin by 395 pg/mL or greater, but multiple criteria exist.6 Serum chromogranin A levels have also been found to be elevated in patients with gastrinomas, and this test may be used to confirm diagnosis in carefully selected cases7 (FIG 1).

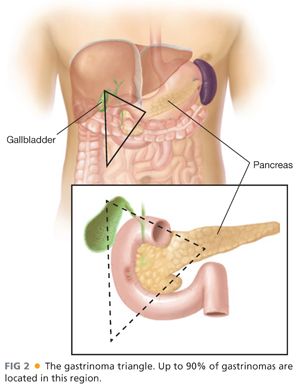

■ After obtaining a biochemical diagnosis of gastrinoma, attention is turned to preoperative localization and staging. Up to 90% of gastrinomas can be located in the area bounded by the junctions of the cystic and common bile ducts, second and third portions of the duodenum, and neck and body of the pancreas—the so-called gastrinoma triangle (FIG 2).

■ Initial localization studies include contrast-enhanced triple-phase protocol computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). The decision to use CT versus MRI should be determined by the clinician based on institutional expertise and availability. Although the accuracy of these modalities continues to improve, the sensitivity for detection of tumors less than 2 cm in diameter is decreased, although lesions as small as 4 mm have been detected.8 EUS can detect smaller lesions (up to 2 to 3 mm, depending on operator experience) and also has the advantage of being able to obtain a cytologic specimen.

■ Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS), also known as OctreoScan, takes advantage of the high level of somatostatin receptor expression in gastrinomas by using radiolabeled 111-indium pentetreotide to detect both primary tumors and hepatic metastases. Although the accuracy of other imaging modalities is improving, SRS continues to have a place in tumor localization and staging as it remains highly sensitive for detection of metastatic disease.9

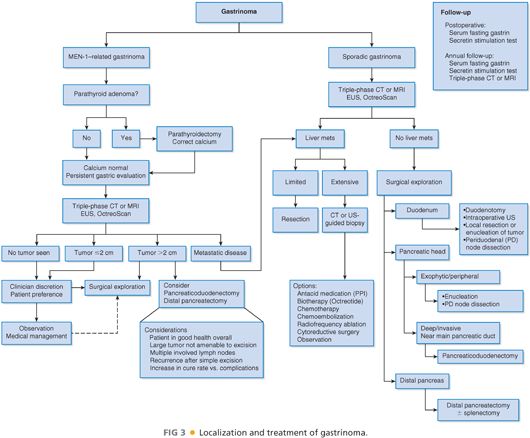

■ Patients determined to have MEN-1–related gastrinoma should be evaluated for hyperparathyroidism. If a primary hyperparathyroidism is present, it should be addressed prior to further surgical treatment as hypercalcemia may increase anesthetic risk and also elevates gastrin and acid production.

■ If the etiology is sporadic and no metastases are detected, then surgical exploration is indicated even if a tumor is not localized by preoperative imaging as these tumors can often be found with careful intraoperative exploration.

■ The risk of liver metastases is increased when tumors are larger than 2 cm.10

■ Patients who present with metastatic disease should undergo resection, if possible, as chemotherapy has limited efficacy in the treatment of gastrinomas. Other modalities, such as radiofrequency ablation, hepatic artery embolization, liver transplantation, and radiolabeled somatostatin therapy, may be considered when anatomic resection is not possible (FIG 3).

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Positioning

■ Patients should be placed in the supine position for exploratory laparotomy to identify gastrinomas.

TECHNIQUES

PLACEMENT OF INCISION

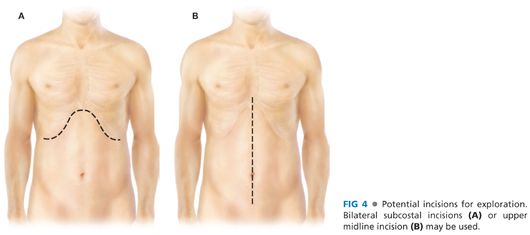

■ Either a bilateral subcostal incision or an upper midline incision may be used to approach the duodenum and pancreas for exploration (FIG 4).

Exploration and Kocher Maneuver

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree