■ Other variants not shown include fibrotic ducts and porta with a patent gallbladder and distal CBD.

■ The “surgically correctable” form of biliary atresia is rare (10% of cases). In this situation, there is patency of a proximal segment of hepatic and/or common duct.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ The differential diagnosis of a mixed hyperbilirubinemia in an infant includes the following:

■ Biliary atresia

■ Neonatal hepatitis

■ α1-Antitrypsin deficiency

■ Other metabolic deficiencies

■ Alagille’s syndrome (biliary hypoplasia, pulmonary stenosis, vertebral anomalies, and elfin facies)

■ Choledochal cyst

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

■ Infants are usually referred at approximately 6 to 8 weeks of age, placing a premium on rapid evaluation, diagnosis, and scheduling of operation. They typically present for evaluation of a mixed hyperbilirubinemia and the primary physical findings are jaundice and hepatomegaly. They also have acholic stools and dark urine.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ Laboratory: The hallmark of the laboratory evaluation is a mixed hyperbilirubinemia. Investigations will be focused on excluding neonatal hepatitis, metabolic diseases, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

■ Nuclear medicine: Technetium-based hepatobiliary scans are often used in the evaluation of infants with a mixed hyperbilirubinemia. Pretest preparation with phenobarbital for 3 to 5 days is useful. Visualization of the tracer in the duodenum/small intestine excludes biliary atresia. Slow uptake is indicative of a global hepatocyte dysfunction.

■ Ultrasound: Imaging is usually supportive of the diagnosis of biliary atresia but is not definitively diagnostic. Usually, there is a thickened, contracted gallbladder and difficulty visualizing the extrahepatic biliary tree.

■ Percutaneous liver biopsy: Recently, percutaneous needle biopsy has become one of the most definitive diagnostic tests in the evaluation of biliary atresia. The histologic appearance is that of any bile duct obstruction: portal tract edema and fibrosis, bile duct proliferation, and stasis. Mimics of biliary atresia are giant cell hepatitis, as it has some similar findings, most notably multinucleated giant cell infiltrates that can also occur with biliary atresia. Similar findings occur with Alagille’s syndrome, which is characterized by biliary hypoplasia but associated with a characteristic elfin facies, pulmonary stenosis, and vertebral anomalies.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

■ An important issue in the surgical management of patients with biliary atresia is the timing of the operation. In general terms, earlier is better. Results are better if the operation is performed before the infant reaches 6 weeks of age. Portoenterostomy may be reasonable up to 120 days of age, recognizing that the prognosis declines rapidly with delayed intervention.

Preoperative Planning

■ Ensure that there is no coagulopathy. If present, must be treated with vitamin K (phytomenadione, 1 mg per day intramuscularly) and/or fresh frozen plasma replacement. Typically, a central vascular catheter or arterial line is not necessary. Epidural catheter anesthesia is a useful adjunct to intra- and postoperative pain management. A second- or third-generation cephalosporin should be administered prior to incision and continued until transition to oral cholangitis prophylaxis can be achieved.

Positioning

■ The patient is placed in the supine position. A small towel roll is positioned transversely under the patient at the level of the lower chest/abdomen.

TECHNIQUES

■ The authors recommend proceeding directly to an open exploration and cholangiogram. If positive, a classic Kasai portoenterostomy biliary drainage procedure is performed. The use of a laparoscopic approach has been associated with significantly worse outcomes.1,2

INCISION

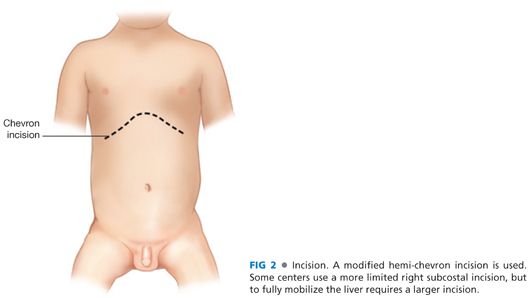

■ Initially, a small right-sided subcostal incision is made to perform the cholangiogram and then extended to facilitate the procedure once confirmation of the diagnosis has occurred. (FIG 2).

CHOLANGIOGRAM

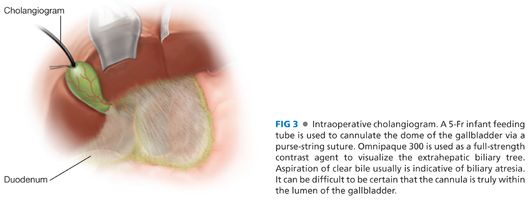

■ The gallbladder is identified; it is usually small and contracted with clear or milky bile in the lumen. A purse-string suture of 5-0 silk on a TF needle (or equivalent) is used and a cholecystotomy is made of a size to admit a 5-Fr infant feeding tube (FIG 3). Nondiluted Omnipaque 300 is injected under fluoroscopic visualization. If there is no visualization of the intrahepatic biliary tree, the distal porta hepatis should be occluded to promote visualization of the proximal hepatic ducts. If there is nonvisualization of the intrahepatic biliary tree, this typically confirms the diagnosis of biliary atresia.

LIVER BIOPSY

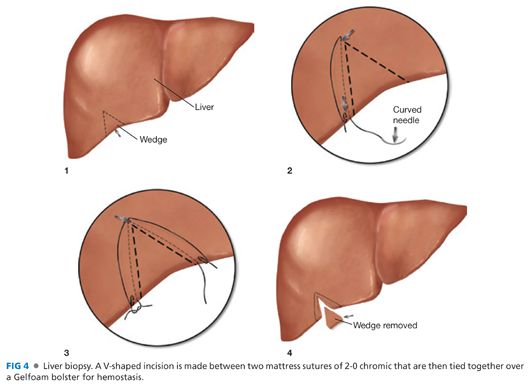

■ With more liberal use of percutaneous biopsy, there is little need for a redundant biopsy at the time of portoenterostomy. However, a classic biopsy that provides a larger sample is often informative regarding degree of liver injury and is essential when a percutaneous biopsy has not been obtained. This is performed as depicted in FIG 4. Using a 2-0 chromic suture on an SH or equivalent needle, two mattress-type sutures are placed in a “V” configuration from which the wedge biopsy will be obtained. A no. 15 blade knife is used to excise a wedge of liver, and the bed is coagulated with the cautery. The tails of the chromic suture are left long and used to reapproximate the edges of the liver over a Gelfoam bolster that renders the field hemostatic. This should be done immediately after the cholangiogram to optimally ensure the site is hemostatic at the conclusion of the procedure and to prevent inadvertent omission of the biopsy following the main portion of the procedure—the portoenterostomy.

HEPATIC MOBILIZATION

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree