Operative Palliation of Pancreatic Cancer

Kaye M. Reid-Lombardo

Joshua Barton

Michael G. Sarr

Introduction

The role of the surgeon in the palliation of patients with unresectable periampullary/ pancreatic cancer has changed markedly over the last decade. In the past, most patients were treated by exploratory celiotomy and, if the lesion was unresectable (80% to 90% of patients), the surgeon would construct an intraoperative bilioenteric bypass and often a gastroenterostomy that was either therapeutic (i.e., treating established duodenal obstruction) or prophylactic [i.e., used to “prevent” gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) caused by pancreatic cancer]. More recently, marked improvements in imaging (spiral, triple-phase computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging) and the use of staging laparoscopy have led to the majority of unresectable cancers being identified prior to celiotomy. This better selection of potentially resectable patients avoids the need for operative biliary and duodenal bypasses, because patients with non-curable disease by resection are now palliated by nonoperative means, both by endobiliary stents and, should duodenal obstruction occur, by endoduodenal stents. Moreover, the marked improvements and expertise with endoscopically placed endobiliary stents and/or percutaneous, transhepatic stents have, in most patients, all but eliminated the need for a planned, operative, palliative bilioenteric bypass. In addition, the ongoing development of intraluminal intestinal stents (partially covered duodenal endoprostheses) has, in many patients, served to relieve the duodenal obstruction from a locally advanced pancreatic cancer, thereby preventing the need for operative gastrojejunostomy. Nevertheless, the surgeon still maintains a definite role to play in the palliation of selected patients with pancreatic cancer, and the approaches/techniques described below offer different advantages for biliary and GOO.

Surgeons have and will continue to play an active role in the palliation of advanced, incurable pancreatic cancer in selected situations. Palliation should be considered from three aspects, all of which are designed to palliate specific symptoms prior to the eventual death of the patient: (1) relief of mechanical extrahepatic biliary obstruction, (2) relief or prevention of mechanical GOO, and (3) minimization/prevention of the all-too-often debilitating pain from the invasion of pancreatic cancer into the peripancreatic and celiac plexus.

Biliary bypass: Once the bile duct becomes obstructed by most malignant neoplasms, the progression of hyperbilirubinemia is relentless at 1 mg/dl/day up to a concentration of 20 to 25 mg/dl. At this level, the spillover into the urine and the soft tissues equals the metabolic daily production, at least for several weeks. Thereafter, the serum bilirubin concentration again increases as the hepatopathy of chronic complete biliary obstruction (biliary cirrhosis) progresses.

Relief of the biliary obstruction should be the first objective of palliation. Biliary obstruction and the absence of bile salts/lectin in the gut lumen not only lead to a maldigestion of fats (loss of solubilization of intraluminal lipids) with resultant malabsorption and exacerbation of weight loss, but also for the patient, the associated pruritus is usually the most distressing. This pruritus on occasion can be the first symptom of the disease, and in the absence of back pain, often becomes the most prominent symptom for the patient.

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO): Duodenal obstruction is a very uncommon, initial presentation of pancreatic cancer (<10%). In contrast, GOO develops later in the course of the disease in up to 15% to 30% of patients, depending on how intensely one looks for this condition; indeed, many patients ultimately die with and/or from GOO. Therefore, if GOO can be prevented without adding much morbidity, some consideration should be given to addressing its prevention in selected patients and in relieving the GOO with, if possible, a minimal access or endoscopic intervention. There is a poorly understood form of “functional” GOO that can complicate the management of unresectable pancreatic cancer that is believed to be a disorder of coordinated gastric emptying. This functional GOO is not a mechanical obstruction of the duodenal lumen but rather related presumably to local neural involvement with a subsequent gastroduodenal dysmotility. This type of GOO does not resolve with gastrojejunostomy and is difficult to treat.

Back pain: As the disease progresses, 60% to 80% of patients with pancreatic cancer eventually develop substantive epigastric pain and especially a “boringthrough” back pain. This back pain is most prominent at night. Part of the concern of the physician/surgeon offering palliative care to the patient with unresectable pancreatic cancer must involve an aggressive approach to the patient with this horrible, often debilitating pain. As surgeons, we also have a primal role in this aspect of palliation. In addition to emotional support, provision of adequate analgesics are imperative, and many times, recruitment of the experts in this field—both the palliative care group and the hospice care team—may be the best therapy that a truly caring surgeon can administer.

In summary, palliative care provided by the surgeon should be threefold: relief of biliary obstruction, relief/prevention of GOO, and aggressive approaches to minimize or prevent pain. The remainder of this chapter will address (1) operative approaches to establish a bilioenteric bypass, (2) use of gastrojejunostomy to treat or prevent GOO, (3) intraoperative chemical splanchnicectomy or thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy to prevent the development of back pain, (4) minimal access (laparoscopic) approaches to the management of biliary and duodenal obstruction, and finally (5) several other adjunctive possibilities. A brief discussion of local ablative techniques, such as intraoperative radiation therapy, cryotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation will also be addressed.

Operative Approaches to Establish Bilioenteric Drainage

Most pancreatic cancers arise either periampullary or within the proximal-most pancreatic duct up to the genu of the duct in the head of the gland; as they enlarge radially, they encroach on and surround the distal “intrapancreatic” portion of the common bile duct (CBD) which is only 5 to 10 mm away. Therefore, pancreatic cancer of only 2 cm

diameter can lead to complete biliary obstruction before it causes any other overt symptomatology—thus, the term “painless jaundice.” While most of these patients in retrospect do have some other symptoms (vague upper abdominal distress, minor weight loss, or unexplained fatigue), the symptoms bringing them to their physician are usually jaundice and pruritus.

diameter can lead to complete biliary obstruction before it causes any other overt symptomatology—thus, the term “painless jaundice.” While most of these patients in retrospect do have some other symptoms (vague upper abdominal distress, minor weight loss, or unexplained fatigue), the symptoms bringing them to their physician are usually jaundice and pruritus.

Bilioenteric bypasses can be constructed in many ways using as the conduit either (1) the gallbladder via cholecystogastrostomy, cholecystoduodenostomy, or cholecystojejunostomy; or (2) the common hepatic duct or CBD by choledocho/hepaticoduodenostomy or choledocho/hepaticojejunostomy. The following section will discuss the technical aspects of these procedures, after which we will address considerations in selection of the optimal form of bilioenteric bypass according to the clinical situation.

Cholecystoenteric Bypass

Technically, using the gallbladder as the biliary conduit is undoubtedly the fastest and the easiest approach to bilioenteric bypass. Distal CBD obstruction usually leads to a markedly dilated gallbladder (Courvoissier’s sign), making access to the gallbladder quite easy. When choosing the gallbladder as the conduit, the surgeon must consider the proximity of the neoplasm to the entrance of the cystic duct into the extrahepatic biliary tree—this consideration will be discussed fully below in the section Selection of Bilioenteric Bypass.

Historically, cholecystogastrostomy and/or cholecystoduodenostomy were the early operations for bilioenteric bypass because of the proximity of the gallbladder to these organs and because of the ease (and safety) of the anastomosis. Mobilization of the fundus of the dilated gallbladder without disruption of the cystic artery will allow the gallbladder to be “folded over” for anastomosis to the stomach or duodenum. Enthusiasm for this procedure waned in the 1960’s as more evidence developed showing problems with bile gastritis/esophagitis, bilious vomiting, and ongoing problems when the duodenum became obstructed from local progression of the pancreatic neoplasm. This approach to bilioenteric bypass is largely of historic interest even in benign conditions because of the reasons described above, but also because the anastomosis often strictures over time (not really a problem when used in the palliation of pancreatic cancer).

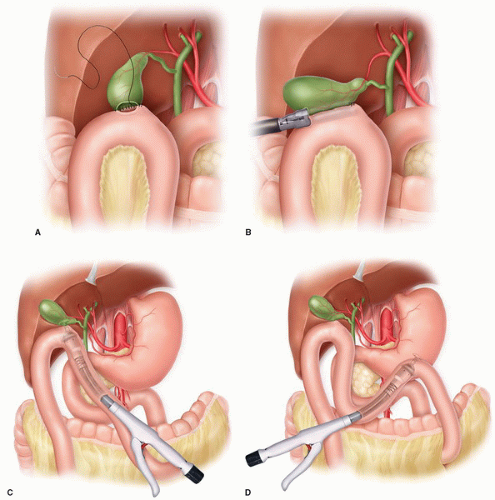

Cholecystojejunostomy: Due to the mobility of the jejunum, this anastomosis is the quickest, easiest, and safest form of bilioenteric drainage and does not require any mobilization of the gallbladder. A loop of proximal jejunum is brought antecolic and sewn to the anterior aspect of the gallbladder fundus; in rare cases, a retrocolic approach through the right transverse mesocolon may be easier, but usually not. The anastomosis can be created in a hand sewn, usually one layer fashion due to the thin-walled gallbladder (Fig. 5.1A), or in stapled fashion (Fig. 5.1B); if a gastrojejunostomy is also planned, an intraluminal circular stapler can be introduced in the enterotomy to be used for the gastrojejunostomy and passed distally to a site where a stapled circular anastomosis can be created (usually a 21 or 25 mm stapler is sufficient) (Fig. 5.1C). Some surgeons then create a Braun-type, side-to-side enteroenterotomy between the afferent and efferent limbs of the loop cholecystojejunostomy but most do not believe this diverting enteroenterostomy to be necessary. Overall, this is a very safe anastomosis with little morbidity.

One very important point needs to be stressed. Strong consideration needs to be directed at the possibility of future obstruction of the cystic duct where it enters the CBD as the pancreatic neoplasm enlarges; obstruction of the cystic duct will lead to recurrent biliary obstruction. If contemplating a cholecystojejunostomy, the gallbladder should be dilated or, if chronically inflamed, should contain bile. Some advocates of this easy anastomosis suggest a cholecystogram to confirm both patency of the cystic duct outflow as well as the site of entrance of the cystic duct into the CBD and its distance from tumor. If the cystic duct enters the CBD low near the duodenum, or if the neoplasm is in close proximity to the entrance of the cystic duct, using the gallbladder as the biliary conduit is contraindicated.

Hepaticoenteric Bypass

Most HPB surgeons currently use the common hepatic duct as the biliary conduit for a palliative bilioenteric bypass. The rationale behind this somewhat more involved approach than using the gallbladder or the CBD is because of worry related to local progression of the pancreatic neoplasm potentially involving the entrance of the cystic duct into the CBD and/or involving the CBD and/or any anastomosis to the CBD. Being several centimeters rostral, the common hepatic duct is involved only rarely with direct spread from a pancreatic neoplasm or only very late in the disease.

Choledochoduodenostomy/hepaticoduodenostomy: When possible, some groups have advocated a choledocho- or hepaticoduodenostomy. The extrahepatic biliary tree

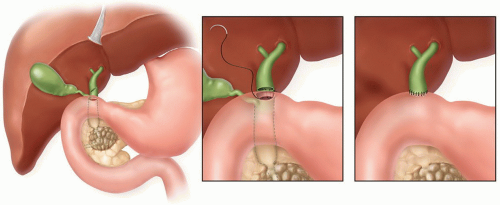

and the duodenum are quite close anatomically and, when the extrahepatic biliary tree is dilated, the anastomosis becomes quite easy. After a Kocher maneuver to gain duodenal mobility, this anastomosis can be done as a side-to-side anastomosis or less commonly by transecting the common hepatic duct at its junction with the CBD, oversewing the distal CBD, and carrying out an end-to-side hepaticoduodenostomy (Fig. 5.2); the latter requires circumferential dissection around the common hepatic duct and oversewing of the CBD, which seems unnecessary if a more simple, straightforward, side-to-side hepaticoduodenostomy is feasible technically. This anastomosis is straightforward, facile, and safe. Usually a cholecystectomy is also performed.

and the duodenum are quite close anatomically and, when the extrahepatic biliary tree is dilated, the anastomosis becomes quite easy. After a Kocher maneuver to gain duodenal mobility, this anastomosis can be done as a side-to-side anastomosis or less commonly by transecting the common hepatic duct at its junction with the CBD, oversewing the distal CBD, and carrying out an end-to-side hepaticoduodenostomy (Fig. 5.2); the latter requires circumferential dissection around the common hepatic duct and oversewing of the CBD, which seems unnecessary if a more simple, straightforward, side-to-side hepaticoduodenostomy is feasible technically. This anastomosis is straightforward, facile, and safe. Usually a cholecystectomy is also performed.

Arguments against this approach cite the potential for anastomotic obstruction in conjunction with duodenal obstruction from local extension of the pancreatic neoplasm. An increasing number of proponents with good, long-term data maintain that (1) this approach requires only one, easy, safe anastomosis, (2) late obstruction of the anastomosis is rare, and (3) when the more distal duodenum becomes obstructed, biliary drainage can still occur retrograde through the stomach and a gastrojejunostomy. The more limited reported experience appears quite good, and the arguments against hepaticoduodenostomy are largely theoretic and not actually supported by objective data.

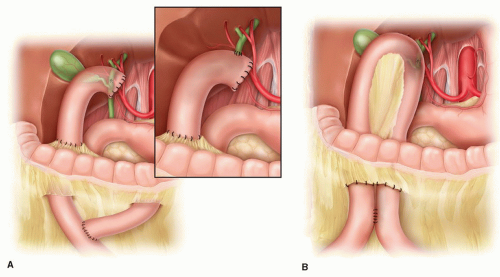

Hepaticojejunostomy: Most HPB surgeons prefer enteric biliary drainage via the common hepatic duct based on the theoretic argument that the chance of future malignant obstruction by local extension of the pancreatobiliary neoplasm is much less likely—see “Selection of Bilioenteric Bypass”. Hepaticojejunostomy can be carried out either to a loop of jejunum or more commonly to a Roux limb (Fig. 5.3). The latter is usually preferred for technical ease. Bringing the intestinal conduit (loop of jejunum or Roux limb) up to the hepatic duct is much easier technically and a much shorter distance via a retrocolic approach through the right transverse mesocolon rather than up and over the omentum and right transverse colon; bringing up a jejunal loop through the mesocolon is more bulky, and worry always remains about obstruction of the loop at the mesocolon; therefore, a Braun-type enteroenterostomy (a second anastomosis) is also usually created. A Roux limb is less bulky, more mobile, and easier to work with than the loop. The argument that a Roux drainage requires the potential morbidity of a second anastomosis (end-to-side jejunojejunostomy) is offset by the ease of construction of the hepaticojejunostomy and the usual construction of a Braun enteroenterostomy with the loop construction anyway. Any worry about reflux of enteric chyme into the

biliary tree should not be of concern, because this procedure is palliative, and prolonged survival greater than 2 years is unexpected. As with hepaticoduodenostomy, if the gallbladder is still in situ, most surgeons will add a cholecystectomy for several reasons: (1) the dilated gallbladder can be “in the way,” and (2) by bypassing the gallbladder, there can be stasis in the gallbladder lumen, which can lead to cholecystitis requiring intervention, a condition that no one would want to develop in a patient with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cholecystectomy is easy and adds minimal morbidity.

biliary tree should not be of concern, because this procedure is palliative, and prolonged survival greater than 2 years is unexpected. As with hepaticoduodenostomy, if the gallbladder is still in situ, most surgeons will add a cholecystectomy for several reasons: (1) the dilated gallbladder can be “in the way,” and (2) by bypassing the gallbladder, there can be stasis in the gallbladder lumen, which can lead to cholecystitis requiring intervention, a condition that no one would want to develop in a patient with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Cholecystectomy is easy and adds minimal morbidity.

The hepaticojejunostomy can be constructed either in a side-to-side or end-to-side fashion (Fig. 5.3). These authors see no benefit of transecting the common hepatic duct to carry out an end-to-side hepaticojejunostomy, which requires its circumferential mobilization and oversewing of the CBD distally, although some surgeons prefer this technique. A side-to-side anastomosis is equally easy to construct. The anastomosis is usually a one-layer technique; if the biliary tree is adequately dilated, a running technique is faster. Again, because this is a palliative procedure, either absorbable or permanent 3- or 4-0 suture material is appropriate. A second serosal layer to the periductal tissues can be added if so desired. Use of any form of decompressive biliary “T-tube” or retrograde bilio-external drainage tube is unnecessary unless the surgeon is very worried about the integrity of the anastomosis for some reason. Anastomotic leak should be rare (<2%). Presence of an endobiliary stent placed preoperatively can either be removed retrograde through the hepatic ductotomy at the time of hepaticojejunostomy or, if there is any concern about the operative anastomosis, the stent can be left to provide another pathway of enteric drainage/decompression but will necessitate endoscopic removal postoperatively. Overall, this procedure has proven to be a very safe, durable anastomosis.

Cholangiojejunostomy

The need for any type of intrahepatic enteric bypass would be extremely unusual as a technique of operative palliation. Situations that might in very rare cases justify such

an approach would involve extensive nodal disease extending up the hepatoduodenal ligament. Possible operative procedures in this situation might involve a left hepatic duct-jejunostomy after taking down the hilar plate with a Hepp-Couinaud type of anastomosis, a segment 3 approach (ligamentum teres approach), or the classic Longmire, left-sided cholangiojejunostomy after excising the lateral most aspect of segment 2 of the liver. These procedures are largely of historic interest, because currently, such extensive involvement of the hepatoduodenal ligament would not have escaped notice on imaging preoperatively (i.e., intrahepatic biliary dilation with dilated extrahepatic ducts) which indicates unresectable disease; should the patient require operative palliation for some other complication (e.g., duodenal obstruction), biliary decompression would be attained by a percutaneous biliary drain without the increased morbidity of one of these intrahepatic bilioenteric bypasses.

an approach would involve extensive nodal disease extending up the hepatoduodenal ligament. Possible operative procedures in this situation might involve a left hepatic duct-jejunostomy after taking down the hilar plate with a Hepp-Couinaud type of anastomosis, a segment 3 approach (ligamentum teres approach), or the classic Longmire, left-sided cholangiojejunostomy after excising the lateral most aspect of segment 2 of the liver. These procedures are largely of historic interest, because currently, such extensive involvement of the hepatoduodenal ligament would not have escaped notice on imaging preoperatively (i.e., intrahepatic biliary dilation with dilated extrahepatic ducts) which indicates unresectable disease; should the patient require operative palliation for some other complication (e.g., duodenal obstruction), biliary decompression would be attained by a percutaneous biliary drain without the increased morbidity of one of these intrahepatic bilioenteric bypasses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree