■ In an elective practice, the majority of distal pancreatectomies will be precipitated by suspicion for malignancy,1 and those being performed open will likely have been selected as such, secondary to local extension of disease. This chapter will thus focus on oncologic principles of resection.

■ A relevant history and physical examination in the setting of potential malignancy should include a detailed past medical history with discussion of known pancreatic cancer risk factors such as family history of pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis, history of diabetes, obesity, and smoking. Character, duration, and mitigating factors of any abdominal or back discomfort or sensations should be discussed and considered carefully to guide differential diagnosis.

■ Medical comorbidities as well as cardiovascular and pulmonary functional status should be evaluated, and any relevant testing needed for preoperative clearance such as stress echocardiograms or pulmonary function tests should be performed in accordance with anesthesia guidelines.2

■ A detailed past surgical history and special attention to family history can help identify patterns of hereditary malignant disease, which can in turn guide preoperative decision making, postoperative surveillance, and genetic testing of the patient and their families. If a neuroendocrine tumor is suspected, symptoms of functional tumors such as rash, diabetes, diarrhea, hypoglycemia, and signs of peptic ulcer disease should be discussed.

■ A thorough physical exam should evaluate for any abdominal abnormalities such as organomegaly. Splenomegaly should raise concern for segmental portal hypertension, which could be precipitated by tumor thrombosis or vascular invasion. Hepatomegaly can imply the presence of hepatic metastases. Special attention should also be paid to a patient’s nodal basins, specifically left supraclavicular and periumbilical nodes to evaluate for any palpable nodal metastases that would prompt a workup.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ The nature of preoperative testing depends heavily on the nature of the diagnosis. Most conditions will warrant further definition with laboratory evaluations and contrasted, cross-sectional imaging, at times, in conjunction with endoscopic ultrasound for tissue diagnosis and for definition of a pancreatic lesion as it relates to surrounding structures.

■ Laboratory testing should include a complete blood count and a comprehensive metabolic panel, including evaluation of liver enzymes and amylase. A preoperative carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) level is important for postoperative surveillance and can contribute to decision making when neoadjuvant therapy is being considered. When an endocrine tumor is suspected, functional urine and relevant hormone stimulation tests should be performed. If a patient has experienced substantial weight loss, a prealbumin level can be helpful in establishing nutritional status and can guide recommendations for perioperative supplemental alimentation, if appropriate.

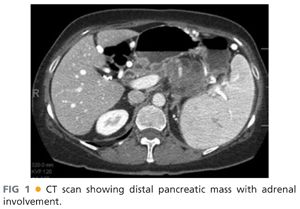

■ Preoperative workup of a pancreatic mass or injury should almost always include a contrasted, cross-sectional imaging study. Although there is some debate regarding the optimal choice of imaging modality, the most common standard is a computed tomography (CT) “pancreas protocol,” which is a triple-phase CT that allows evaluation of arterial, pancreatic, and portal venous phases, and is critical to determining resectability and to establishing an appropriate operative plan. Three-dimensional reconstruction, where available, can also add insight regarding resectability. FIG 1 demonstrates a lesion with adrenal involvement that would be appropriate for radical antegrade distal pancreatectomy.

■ In the case of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, many surgeons use magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in order to assess cystic nature and communication with the main pancreatic duct or side branch ducts in order to further characterize risk of cystic lesion.

■ Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is another available tool that can elucidate possible lymph node metastases and confirm spatial relationships between a mass and peripancreatic vasculature. EUS can also secure a tissue biopsy of the mass and any suspicious lymphadenopathy as relevant. EUS is not always needed if surgical planning can be completed with cross-sectional imaging, and the results of the EUS would not change the surgical plan. Multidisciplinary collaboration between surgeons and gastroenterologists is important to ensure the appropriate information is gathered and conveyed.

■ The role of positron emission tomography (PET)-CT in pancreatic cancer staging for consideration of resection is currently poorly defined and is not currently considered standard of care.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Preoperative imaging guides surgical treatment. Location of a tumor to the left of the superior mesenteric vessels obviates the possibility of successful disease eradication with a distal or subtotal pancreatectomy. The imaging studies mentioned earlier should be reviewed thoroughly. Close attention should be paid to the planned resection margins, as they relate to surrounding organs and vasculature; particular attention must be given to the retroperitoneal margin, major mesenteric and celiac vessels, left adrenal gland, and left renal vasculature and kidney. If a portion of the colon is involved, a bowel preparation should be considered in anticipation of en bloc colonic resection.

■ The anesthesiology team should be informed in advance if a surgeon anticipates an arduous dissection that poses a risk for significant hemorrhage. A type and screen should be drawn on all patients to facilitate blood availability in case of emergent need.

■ In addition to adequate peripheral or central intravenous access, a Foley catheter, nasogastric tube, and arterial line should be placed.

■ Preoperative antibiotics should be administered within 1 hour of incision. Coverage should be broad spectrum and should include gram-positive skin flora as well as gram-negative and anaerobic intestinal pathogens.

■ The entire abdomen from nipples to pubis should be shaved including flanks, even if a midline incision is anticipated. This facilitates subcostal and perixiphoid incisional extension if needed.

Positioning

■ The patient is positioned supine with arms out unless precluded by patient shoulder mobility. The secure placement of the post of a self-retaining retractor should be considered.

TECHNIQUES

INCISION

■ Left subcostal and midline incisions are both reasonable choices; obesity and costal margin angularity should influence the exposure. Incision location varies based on patient body habitus, tumor location, and surgeon preference. Generally, a slender patient or a patient with a sharp costal margin angle is appropriate for a midline incision as this incision is less morbid. Other candidates for a midline incision are patients with previous midline incision and those with tumors closer to the midline. In obese patients or those with a particularly high splenic flexure or a tumor that is quite distal on the pancreas, a subcostal incision may provide enhanced visualization of the left upper quadrant.

■ A vertical midline incision is made from xiphoid to just below the umbilicus.

■ A left subcostal incision is made two fingerbreadths below the costal margin and is carried from the midline, obliquely to approximately the anterior axillary line.

INITIAL SURVEY AND EXPOSURE

■ The abdomen is explored for signs of extrapancreatic metastases. The liver and peritoneal surfaces are visually examined and palpated. The omentum is examined for caking or nodularity. The gastrohepatic ligament and lymphatic tissues around the celiac plexus are inspected for any evidence of metastasis. Any unexpected findings should be biopsied and sent for frozen section analysis prior to an extensive dissection. When a distal pancreatectomy is anticipated, the head of the pancreas should also be examined and palpated in order to confirm the absence of major abnormalities.

■ A self-retaining Omni-Trak or Bookwalter retractor should be placed. Our institutional preference is the Omni-Trak retractor as this provides superior exposure in the upper abdomen using the sternal retractors to elevate the costal margin.

■ The splenic flexure is mobilized and reflected downward. In select patients, one may consider laparoscopic mobilization of the splenic flexure and division of the short gastric vessels prior to open distal pancreatectomy to allow for a more limited incision.

EXPOSURE OF THE PANCREAS

■ The gastrocolic ligament is divided to gain entry into the lesser sac. The transverse colon is gently retracted inferiorly, taking care not to avulse the middle colic vein as it inserts into the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) at the inferior neck of the pancreas.

■ The short gastric vessels are divided with an energy device, or rarely between clamps and ties. Any posterior gastric attachments to the pancreas are divided and the stomach is retracted superiorly to expose the anterior surface of the pancreas.

■ In the case of a small lesion that is not readily visualized, the inferior attachments of the pancreas can be freed to facilitate posterior palpation. At the inferior border of the pancreas, gentle separation of pancreatic parenchyma from posterior attachments can be achieved. The splenic vein can be identified and isolated just to the left of its union with the portal vein (PV) usually beneath the pancreas. Intraoperative ultrasound can also be used to locate small lesions in the tail of the pancreas that are not readily identified.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree