Unfortunately, endoscopic ulcers are not ideal surrogate outcomes for clinical gastrointestinal events such as bleeding or perforation of an ulcer. In fact, the proportion of endoscopic ulcers that never become clinically symptomatic, is estimated to be as high as 85% [13, 51].

With the publication of several large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that used actual clinical endpoints to measure the safety of COX-2 inhibitors and of misoprostol prophylaxis [13, 52, 53], it became possible to compare the reduction in clinical events with that of the reduction in endoscopic ulcers from the endoscopic studies [54–56]. Although these are indirect comparisons that have to be interpreted with caution, we have found in our systematic reviews that the standard NSAID arms of both the NSAID prophylaxis trials and the COX-2 trials were quite similar clinically, and demonstrated nearly identical NSAID ulcer and complication rates.

The relative risk reduction in endoscopic gastric ulcers with misoprostol prophylaxis and with COX-2 inhibitors is about 80%. In the clinical endpoint studies, the relative risk reductions in NSAID ulcer related perforations, obstructions and bleeding is about 50% with both these strategies. The consistency suggests that there is a relationship between the endoscopic and clinical endpoints. The relationship does not have to be 1:1. In fact based on our results, prophylactic agents and COX-2 inhibitors are 1.5–2.0 times more effective at reducing the risk of endoscopic ulcers than they are at reducing the risk of clinical endpoints. Unfortunately the studies using clinical gastrointestinal events as the primary outcome measure were not designed to look at the relationship of clinical events to endoscopic ulcers, and we used indirect comparisons to arrive at this result [13]. However, with the cautions described above, the reader can estimate what the expected reduction in clinical events would be based on the results of an endoscopic end-point study, assuming the control groups are average risk arthritic patients requiring long-term NSAID use.

The role of Helicobacter pylori in NSAID associated ulcers

The causal role of Helicobacter pylori in the development of gastroduodenal ulcers has added a new perspective to the management of patients with gastrointestinal complaints [57–59]. NSAIDs are now thought to cause approximately 25% of gastroduodenal ulcers [60], and do so in the absence of H. pylori [61–64]. The study of the potential interaction between H. pylori and NSAIDs has been complicated by the following facts: (1) NSAID use is most frequent among elderly patients, the same group with the highest H. pylori prevalence in western populations [65, 66], (2) in the presence of both factors, it has been difficult to determine whether an ulcer is caused by NSAIDs with incidental H. pylori, or caused by H. pylori with incidental or exacerbating NSAIDs [67, 68], and (3) whereas one would expect, based on conventional thinking, an increased incidence of ulcers in the presence of these two well-established risk factors, some clinical and observational studies found that infection with H. pylori decreased the likelihood of ulcers or gastroduodenal injury in NSAID users [69–72]. Still other studies have found no effect of H. pylori infection on NSAID induced gastroduodenal injury [70, 73].

A systematic review published in 2002 has shed some light on our understanding of the clinical impact of the coexistence of H. pylori infection and NSAID use [74]. In this systematic review of observational studies of PUD in adult patients taking NSAIDs and of H. pylori infection and NSAID use in PUD bleeding, strict diagnostic criteria for the documentation of H. pylori infection and endoscopic ulcers were used. Twenty-five studies were included out of 61 potentially relevant publications. Sixteen studies with a total of 1625 patients assessed the effect of H. pylori infection on the risk of uncomplicated PUD in adult NSAID users. In these patients, H. pylori infection increased the risk of uncomplicated PUD 2.12-fold (95% CI: 1.68–2.67).

The interaction between H. pylori infection and NSAID exposure was derived from five age-matched controlled studies of chronic (>4 weeks) NSAID exposure. In the presence of H. pylori infection, the use of NSAIDs increased the risk of uncomplicated PUD 3.55-fold (95% CI: 1.26–9.96); while in the presence of NSAIDs, H. pylori infection increased the risk of PUD 3.53-fold (95% CI: 2.16–5.75). Compared to control patients without either NSAID or H. pylori exposure, the combined exposure to both factors increased the risk of uncomplicated PUD 6.36-fold (95% CI: 2.21–18.31) after correction for a zero event rate in H. pylori negative controls.

Nine case-control studies with 893 patients and 1002 controls assessed the effects of H. pylori infection and NSAID exposure on the risk of ulcer bleeding. H. pylori infection conferred a marginally increased risk, with an OR 1.67 (95% CI: 1.02–2.72), which was more pronounced when the analysis was limited to studies using serology for diagnosis of H. pylori infection (OR 2.16 (95% CI: 1.54–3.04)). Studies using patients with non-bleeding ulcers as controls (as opposed to either healthy or hospitalized non-ulcer controls) tended to be negative, but the results of a sensitivity analysis based on the type of controls were not presented. NSAID exposure, which was principally short term in these studies (<1 week and <1 month in six and two out of nine studies respectively), conferred an increased risk of ulcer bleeding (OR 4.79; 95% CI: 3.78–6.06), whereas the combined exposure to NSAIDs and H. pylori led to an increased risk of PUD bleed of 6.13 (95% CI: 3.93–9.56). These findings are in keeping with the hypothesis that short-term NSAID exposure renders “silent” H. pylori-related ulcers clinically manifest, a notion that has been suggested by others [75–77].

The authors of this systematic review support the conventional thinking that in peptic ulcer disease two sources of injuries are worse than one. However, the outcome of combined exposure to NSAIDs and H. pylori infection differs depending on the patient population (prior history of PUD or not), the type of NSAID exposure (first time or not, short term or long-term; ASA or non-ASA NSAID), the study outcome (ulcer healing, ulcer bleeding, ulcer prevention) and the co-administration of ulcer prophylaxis. Several recent randomized trials have addressed some of these issues.

Ulcer healing

Ulcer healing with omeprazole or ranitidine occurs more readily in the presence of H. pylori infection [78, 79]. As well, the presence of H. pylori enhances the ability of omeprazole to raise gastric pH among patients with duodenal ulcer [80]. However, Bianchi Porro et al. found that the presence of H. pylori did not statistically affect the healing rates at either four or eight weeks in a study of 100 chronic NSAID users with peptic ulcers [81].

In a group of 81 H. pylori positive ulcer patients with ongoing requirement for NSAIDs, Hawkey et al. observed that the addition of H. pylori eradication to a one-month course of omeprazole led to a significantly lower healing rate for gastric ulcers (50 vs 88% healing at four weeks and 72 vs 100% healing at eight weeks, for the H. pylori treated and omeprazole alone groups, respectively (p = 0.006)), while the rates of duodenal ulcer healing were similar in both groups [82].

Ulcer prevention in NSAID naive patients

Chan et al. randomized 100 H. pylori positive, NSAID naive, patients with no prior history of peptic ulcer, to receive either naproxen alone or H. pylori eradication (bismuth, tetracycline and metronidazole) followed by naproxen for eight weeks [83]. At eight weeks, the rate of ulcer recurrence was statistically lower in the triple therapy group (7% vs 26% in the naproxen alone group in the intention-to-treat analysis, p = 0.01), for a 74% relative risk reduction with H. pylori eradication. The importance of coexistent risk factors was highlighted by the fact that 73% of ulcer patients were older than 60 and that 73% of them also had co-morbidity.

In a more recent study, the same group enrolled 100 H. pylori positive, NSAID naive, patients with either a prior history of peptic ulcer (16% of the patients) or dyspepsia, to receive H. pylori eradication or omeprazole plus placebo for one week, followed by diclofenac 100 mg daily for six months [84]. Once again, in these NSAID naive patients, H. pylori eradication conferred a protective effect, leading to a significantly reduced incidence of both endoscopic ulcers (12.1% (95% CI: 3.1–21.1) vs 34.4% (21.1–47.7) in the eradication vs omeprazole alone groups respectively), and of clinical ulcers (4.2% (1.3–9.7) vs 27.1% (14.7–39.5) in the eradication vs omeprazole alone groups respectively) at six months. Of note, 17% of these patients had received low-dose ASA prior to enrolment.

Secondary ulcer prevention in patients on continuous NSAID

The role of H. pylori eradication for the prevention of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding was studied by Chan et al. [85]. Four hundred H. pylori positive, chronic users of ASA or other NSAID, presenting with a bleeding peptic ulcer, were randomized to receive either H. pylori eradication or ulcer prophylaxis with omeprazole and followed up for six months for the recurrence of clinical events. In the group of patients on low-dose (80 mg daily) ASA, the probability of ulcer recurrence was similar among H. pylori treated patients and those on PPI prophylaxis. However, in patients on a non-ASA NSAID (naproxen 500 mg twice daily), H. pylori eradication did not confer the same magnitude of ulcer protection as omeprazole, so that the trial was terminated after the second interim analysis (probability of recurrence 18.8% vs 4.4% for the H. pylori eradication and omeprazole groups respectively (p = 0.005) at that point).

Hawkey et al. studied the role of H. pylori eradication in a group of 285 H. pylori positive patients with a history of ulcer or dyspepsia and ongoing requirement for NSAIDs [82], who were randomized to a one-week course of either H. pylori eradication or omeprazole plus placebo. All patients then received a three-week course of omeprazole for ulcer healing. During the follow-up period patients received continuous NSAIDs without ulcer prophylaxis. The probability of ulcer recurrence at six months was similar in both groups, and the study concluded that in chronic NSAID (non-ASA) users, H. pylori eradication did not confer a protective effect on ulcer recurrence.

In summary, we can conclude based on these recent RCTs, that H. pylori contributes to an excess ulcer risk in NSAID naive patients, whereas ulcers occurring in long-term NSAID users are probably largely caused by NSAIDs themselves, irrespective of H. pylori status. Therefore, the impact of H. pylori is likely to be manifest early in the course of NSAID exposure, either because these patients are prone to early ulcer complications with NSAIDs, or because the administration of NSAIDs has precipitated complications in pre-existing H. pylori ulcers. We can also conclude that the impact of H. pylori eradication is related to the amount of co-existing ulcerogenic factors; while its benefits are more obvious in conjunction with low-dose ASA administration, they are not significant in comparison to the ulcerogenic effects of “regular” NSAIDs and are less marked in the elderly or in the presence of co-morbidity.

Based on this evidence, it would seem appropriate to eradicate H. pylori in NSAID naive patients prior to starting chronic ASA or NSAID therapy. However, H. pylori eradication alone appears to be insufficient for ulcer prophylaxis in chronic non-ASA NSAID users.

Definition of terms

In the discussion that follows, we use the relative risk (RR) to indicate the likelihood of an outcome in subjects on treatment compared to those on placebo [86, 87]. For example a RR of 0.25, means that the treatment is associated with only 25% or 1/4 the probability of the outcome as compared to placebo. Expressed in another way, an RR of 0.25 means that the treatment reduces the “risk” of an event by 75% compared to placebo (1–0.25 = 0.75 or 75%). This relative risk reduction differs from the absolute risk reduction (ARR), the arithmetic difference in the proportion of patients with the outcome between the placebo and treatment groups. If the stated 95% confidence interval overlaps with 1, then the observed risk is not statistically significant. Several clinical endpoints are used in the chapter. The composite endpoint of perforation, obstruction or bleeding is referred to as POB; while a PUB refers to a POB or a symptomatic ulcer. Endoscopic ulcers refer to endoscopically detected ulcers as part of studies with predetermined endoscopy schedules. Non-selective traditional NSAIDs are referred to as tNSAIDs; and cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors as COX-2s. The term NSAID is used when referring to the overall group including (tNSAIDs and COX-2s).

Misoprostol

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue [88–91]. It reduces basal and stimulated gastric acid secretion through a direct effect on parietal cells [91], and reduces gastric damage caused by a variety of aggressive factors including bile salts and NSAIDs [92]. Misoprostol’s protective effects are felt to be related to its ability to stimulate gastric bicarbonate and mucus secretion, and to maintain mucosal blood flow and the mucosal permeability barrier. Misoprostol also promotes epithelial proliferation in response to injury [88]. It appears that at doses of misoprostol sufficient to protect gastric mucosa, suppression of acid secretion also occurs [90]. However, since standard doses of H2-receptor antagonists inhibit gastric acid secretion at least as effectively as misoprostol, and yet have not been shown to protect the gastric mucosa against NSAID induced ulceration (see next section), it is likely that mechanisms other than acid suppression are important for the prevention of gastric ulcers. Additionally, it has recently been suggested that misoprostol may be superior to PPIs for the prevention of NSAID induced gastric ulcers and gastroduodenal erosions [93, 94].

Misoprostol appears to be effective in preventing acute gastroduodenal injury induced by short courses of ASA and NSAIDs as measured by mucosal, or fecal blood loss, and by endoscopic injury scores [95–99]. However the clinical relevance of this effect is unclear, given the adaptation of gastroduodenal mucosa to acute injury with continued NSAID use [73,100,101].

Long-term efficacy of misoprostol

In our meta-analysis, we found 23 studies that assessed the long-term effect of misoprostol on the prevention of tNSAID ulcers [13, 33, 94,102–121]. The dosage of misoprostol varied from 200 ug to 800 ug daily, and follow up ranged between 4 to 48 weeks.

Endoscopic ulcers

Eleven studies with 3641 patients compared the incidence of endoscopic ulcers, after at least three months, in misoprostol and placebo treated patients [94, 102, 103, 106, 110–113, 116, 118, 121]. The cumulative incidence of endoscopic gastric and duodenal ulcers with placebo was 15% and 6%, respectively. Misoprostol significantly reduced the relative risk of gastric ulcer and duodenal ulcers by 74% RR = 0.26; 95% CI: 0.17–0.39 random effects), and 58% (RR = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.22–0.81 random effects). These relative risks correspond to 12.0% and 3% absolute risk reductions for gastric and duodenal ulcers, respectively. The observed heterogeneity in these estimates was due to inclusion of all misoprostol doses in the analyses. Analysis of the misoprostol studies stratified by dose eliminated this heterogeneity.

Analysis by dose

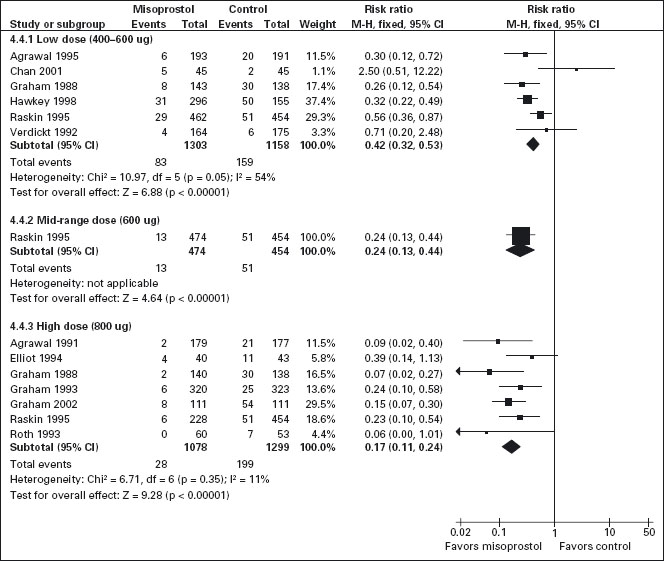

All the studied doses of misoprostol significantly reduced the risk of endoscopic ulcers and a dose response relationship was demonstrated for endoscopic gastric ulcers (Figure 7.1). Six studies with 2461 patients used misoprostol 400ug [103,106, 111, 113, 116, 121], one study with 928 patients used 600ug daily [116], and seven with 2423 patients used 800ug daily [94, 102, 110–112, 116, 118]. Misoprostol 800 ug daily was associated with the lowest risk (RR = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.11–0.24) of endoscopic gastric ulcers when compared to placebo, whereas misoprostol 400 ug daily was associated with a relative risk of 0.42 (95% CI: 0.28–0.67 random effects model for heterogeneity). The observed heterogeneity in the 400 ug dose group was the result of the addition of the Chan study (Chan 2001). This study compared the relatively more toxic naproxen with low dose misoprostol to nabumatone alone. In this study the risk of ulcers was inexplicably greater in the misoprostol group, but this result is probably based on the differences between the safety of the comparator tNSAIDS rather than on an effect of the prophylactic agent. In a sensitivity analysis, removal of the Chan study eliminates the observed heterogeneity without significantly altering the results, giving low dose misoprostol prophylaxis a RR of 0.39 (95% CI: 0.3–0.51). This difference between high and low-dose misoprostol was statistically significant (p = 0.0055). The observed risk for the intermediate misoprostol dose (600 ug daily) was not statistically significantly different from that observed for either the low or high dose. The pooled relative risk reduction of 78% (4.7% absolute risk difference, RR = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.09–0.49) for duodenal ulcers with misoprostol 800 ug daily was not statistically different from those observed with lower daily misoprostol dosages.

Figure 7.1 Misoprostol vs placebo for the prevention of gastric ulcers – efficacy by dose: Misoprosol 800ug/day is superior to 400 or 600ug/day for the prevention of endoscopically detected gastric ulcer.

Studies including data with less than three months’ tNSAID exposure

Eight studies, with 2206 patients, assessed the rates of endoscopic ulcers with misoprostol compared to placebo at 1–1.5 months [33, 104, 105, 107, 109, 110, 114, 119]. The pooling of these studies revealed an 81% relative risk reduction for gastric ulcers with misoprostol (RR = 0.17; 95% CI: 0.09–0.31) and a 72% relative risk reduction for duodenal ulcers (RR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.14–0.56).

One study compared misoprostol to a newer cytoprotec-tive agent, Dosmafate, for tNSAID prophylaxis and found no statistically significant difference in ulcer rates between the two agents [108].

Clinical ulcers

Only one RCT, the MUCOSA trial, evaluated the efficacy of misoprostol prophylaxis against clinically important tNSAID induced ulcer complications as the primary end-point. In this study, of 8843 patients studied over six months, the overall GI event incidence was about 1.5% per year [13]. Misoprostol 800ug/day was associated with a statistically significant 40% risk reduction (OR = 0.598; 95% CI: 0.364–0.982) in combined GI events (p = 0.049), representing a risk difference of 0.38% (from 0.95% to 0.57%).

Adverse effects

Misoprostol was associated with a small but statistically significant 1.6-fold excess risk of drop-out due to drug induced adverse effects, and an excess risk of drop-outs due to nausea (RR = 1.30; 95% CI: 1.08–1.55), diarrhea (RR = 2.36; 95% CI: 2.01–2.77), and abdominal pain (RR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.20–1.55). In the MUCOSA trial, 732 out of 4404 patients on misoprostol experienced diarrhea or abdominal pain, compared to 399 out of 4439 on placebo for a relative risk of 1.82 associated with misoprostol (p <0.001). Overall, 27% of patients on misoprostol experienced one or more adverse effects [13].

When analyzed by dose, only misoprostol 800 ug daily showed a statistically significant excess risk of drop-outs due to diarrhea (RR = 2.45; 95% CI: 2.09–2.88) and abdominal pain (RR = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.17–1.63). Both misoprostol doses were associated with a statistically significant risk of diarrhea. However, the risk of diarrhea with 800ug/day (RR = 3.25; 95% CI: 2.60–4.06) was significantly higher than that seen with 400ug/day (RR = 1.81 95% CI: 1.52–2.16) (p = 0.0012).

In conclusion, misoprostol prophylaxis significantly reduces the risk of ulcers as well as serious gastrointestinal events in patients on long-term NSAID therapy. A1a Misoprostol is more effective at reducing the risk of gastric than duodenal ulcers, and may be more effective than PPIs at reducing the risk of gastric ulcers. The use of misoprostol, particularly at higher doses, is associated with more frequent gastrointestinal adverse effects, often resulting in the patient discontinuing the medication, which is an important consideration, given the symptoms associated with NSAID use alone. The effectiveness outside of clinical trials of misoprostol for prevention of ulcer may be lower than figures which have been presented above. However, since misoprostol is the only prophylactic agent that has been directly shown to reduce serious NSAID related gastrointestinal complications, it should be considered as the first-line agent in the primary prophylaxis of NSAID complications, particularly in high risk groups. A1a

H2-receptor antagonists

Treatment of NSAID induced ulcer

The efficacy of H2-receptor antagonists in the treatment and prevention of NSAID related upper gastrointestinal toxicity has been exclusively evaluated in studies in which ulcers were defined endoscopically. In several early open label studies of cimetidine for healing of ulcers associated with the use of NSAIDs, it was shown that greater than 75% of gastric and duodenal ulcers could be healed with 12 weeks of therapy despite continued use of NSAIDs [122–126]. There was a trend toward improved efficacy with higher doses. However, in a randomized trial in which patients with NSAID – induced ulcers were randomized to receive standard dose ranitidine, or the more potent acid suppressor omeprazole, omeprazole was nearly twice as effective [127], although ranitidine was still somewhat effective [127, 128]. A1a O’Laughlin et al. found that ulcer size correlated inversely with healing rates. At eight weeks, ulcers with a diameter <5 mm were healed in greater than 90% of patients compared to 35% healing for ulcers >5mm [129]. Hudson et al. reported similar observations [130]. The potency of acid suppression and initial ulcer size are important determinants of the rapidity of ulcer healing, and the continued use of NSAIDs in the presence of gastric acid may slow ulcer healing.

Prevention of NSAID- induced ulcers

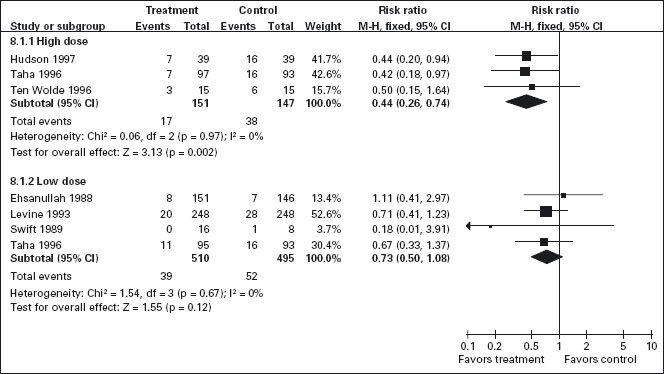

Standard doses of H2-receptor antagonists have been consistently shown to be effective for prevention of endoscopically defined duodenal ulcers, but not of gastric ulcers (Figure 7.2) [117, 131–140]. Koch et al. [141] in a meta-analysis of randomized trials that employed standard doses of H2-receptor antagonists [131–133, 135, 137, 138] and Stalnikowicz et al. [14] were also unable to show a benefit for the prevention of gastric ulcers. Similarly, our meta-analysis of the standard dose H2-receptor antagonist trials confirms that there is no statistically significant reduction in the relative risk of endoscopically defined gastric ulcers [54,55].

Figure 7.2 H2-receptor antagonists compared to placebo for the prevention of gastric ulcers: While all doses of H2-RAs are effective for reducing the incidence of endoscopically detected duodenal ulcers (figure not shown), only high doses of H2-RAs (equivalent to ranitidine 300 mg bid) are effective for reducing the incidence of gastric ulcers.

Six trials that included 942 patients assessed the effect of standard dose H2-RAs on the prevention of endoscopic tNSAID ulcers at one month [131–134, 138, 142], and five trials with 1005 patients assessed these outcomes at three months or longer [131, 134, 135, 140, 143]. Standard dose H2-RAs are effective at reducing the risk of duodenal ulcers (RR = 0.24; 95% CI: 0.10–0.57, and RR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.18–0.74 at one and three or more months respectively), but not of gastric ulcers (NS). One study did not have a placebo comparator and was not included in the pooled estimate [140].

Although achlorhydria has been reported not to prevent early NSAID induced gastric lesions [144], there is accumulating evidence that profound acid suppression can reduce acute NSAID and ASA induced gastric mucosal injury [145–147]. Based on these observations, several investigators have tested the hypothesis that higher doses of H2-receptor antagonists may achieve more consistent acid suppression and may therefore be effective for prevention of gastric ulcer among chronic NSAID users. We identified three RCTs that included 298 patients that assessed the efficacy of double dose H2-RA for the prevention of tNSAID induced upper GI toxicity [130, 134, 148]. Double dose H2-RAs when compared to placebo were associated with a statistically significant reduction in the risk of both duodenal (RR = 0.26; 95% CI: 0.11–0.65) and gastric ulcers (RR = 0.44; 95% CI: 026–0.74). This 56% relative risk reduction in gastric ulcer corresponds to a 12% absolute risk difference (from 23.1% to 11.3%). A1c

Analysis of the secondary prophylaxis studies alone yielded similar results.

Symptoms H2-RAs, in standard or double doses, were not associated with an excess risk of total drop-outs, drop-outs due to adverse effects, or symptoms when compared to placebo. However, high dose H2-RAs significantly reduced symptoms of abdominal pain when compared to placebo (RR = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.33–0.98).

H2-RAs were generally quite well tolerated in the presented studies. Standard doses of these agents appear to be effective in preventing NSAID induced duodenal but not gastric ulcers. However, double dose H2-receptor antagonists appear to be effective for healing and prevention of both gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients taking NSAIDs chronically. The clinical use of this class of drugs for the prevention of gastroduodenal ulceration may be questioned for several reasons. In terms of the trial results, the ulcer rates in the placebo groups of the famotidine studies are higher than are generally reported. Furthermore, since H2-receptor antagonists are associated with tolerance to their acid suppressive effects [149–151], the long-term efficacy of these drugs must be questioned. Finally, even if effective for ulcer prevention, there is no economic or therapeutic advantage to using double doses of these drugs rather than standard doses of proton pump inhibitors that produce more potent and reliable acid suppression. C5

Proton pump inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) block the final step of gastric acid secretion by inhibiting parietal cell H+-K+-ATPase. Direct evidence for the efficacy of PPIs in the primary or secondary prevention of clinically important NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal toxicity is lacking. Several factors have prompted interest in the use of PPIs for prophylaxis against NSAID induced ulcers: (1) dissatisfaction with the adverse effects of misoprostol; (2) the apparent efficacy of PPIs in healing NSAID ulcers; (3) the proven efficacy of PPIs in other acid-peptic disorders; (4) the attractive tolerability profile of PPIs.

PPIs appear to be effective for the prevention of early NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal injury assessed either endoscopically or through the detection of mucosal blood loss, in healthy volunteers given aspirin or naproxen [145–147,152]. However, as discussed previously the clinical relevance of these early lesions is in question.

Healing of ulcers with continued NSAID use

Omeprazole has been shown to heal both gastric and duodenal ulcers irrespective of continued NSAID use [79, 93, 127, 153–155]. Walan et al. in a double-blind trial, assessed the healing rates of benign gastric and prepyloric ulcers in 602 patients randomized to receive either omeprazole (40mg or 20mg) or ranitidine 150mg bid [127]. In a subset of 58 patients with endoscopically documented ulcers who continued to take NSAIDs, the proportions of patients whose ulcers healed at eight weeks were: omeprazole 40 mg, 95% (similar to results for patients with non-NSAID ulcers), omeprazole 20 mg, 82% and ranitidine, 53%, (p < 0.05). These data suggest that selected patients with endoscopically documented NSAID ulcers can experience ulcer healing with omeprazole despite continued NSAID use. However, caution should be exercised in extrapolating these results to patients presenting with NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. In these patients the decision to continue the NSAID must be individualized, since the safety and efficacy of omeprazole in this setting has not been assessed.

NSAID ulcer prevention

Six RCTs with 1259 patients assessed the effect of PPIs on the prevention of tNSAID induced upper GI toxicity [94, 113, 156–159].

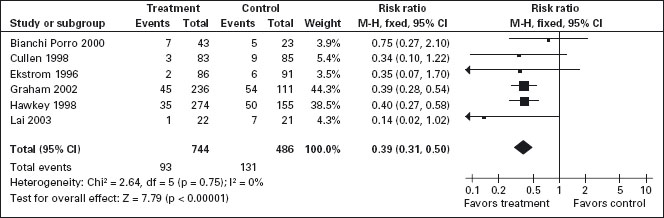

PPIs significantly reduced the risk of both endoscopic duodenal (RR = 0.20; 95% CI: 0.10–0.39) and gastric ulcers (RR = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.31–0.50) compared to placebo (Figure 7.3) [94, 113, 156–159]. The results were similar for both primary and secondary prophylaxis trials. A1a

Figure 7.3 PPIs compared to placebo for the prevention of gastric ulcer in studies of eight weeks or longer duration. PPIs are effective for reducing the incidence of both gastric and duodenal ulcers. Data for gastric ulcers is shown.

Symptoms

Four omeprazole trials used the same composite endpoints to define treatment success [79,113,157,158]. In these trials omeprazole significantly reduced “dyspeptic symptoms” as defined by the authors. In the combined analysis, drop-outs overall and drop-outs due to adverse effects were not different from placebo.

Head-to-head comparisons

Misoprostol vs H2-RAs

Two trials with 600 patients compared misoprostol to ranitidine 150mg twice daily [116, 120]. Misoprostol appears to be superior to standard dose ranitidine for the prevention of tNSAID induced gastric ulcers (RR = 0.12; 95% CI: 0.03–0.51) but not duodenal ulcers (RR = 1.00; 95% CI: 0.14–7.14). A1a

PPI vs H2-RA

Yeomans et al. in a study of 425 patients, compared omeprazole 20 mg daily to ranitidine 150 mg twice daily for tNSAID prophylaxis [79]. In this study, omeprazole was superior to standard dose ranitidine for the prevention of both gastric (RR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.17–0.62) and duodenal ulcers (RR = 0.11; 95% CI: 0.01–0.89). A1a

PPI vs misoprostol

Four trials with a total of 1478 patients [32, 94, 113, 115] compared a PPI to misoprostol. Two studies compared low dose misoprostol (400 ug) daily to a standard dose PPI [32, 113] or high dose misoprostol (800ug) to lansoprazole 15 or 30 mg daily. PPIs are significantly more effective than misoprostol for the prevention of duodenal (RR = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.11–0.56), but not gastric (RR = 1.61; 95% CI: 0.88–3.06 random effects) or total gastroduodenal ulcers (RR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.47–1.72 random effects). A1a The trial conducted by Hawkey et al. showed a non-significant trend towards greater benefit with misoprostol over omeprazole for the prevention of gastric ulcers, while the study reported by Graham et al. actually showed that misoprostol was superior to lansoprazole for the prevention of gastric ulcers. The pooled results mirrored these findings but did not demonstrate a statistically significant benefit of misopostol over PPIs (RR = 0.62; 95% CI: 0.33–1.18 random effects).

Symptoms

In the two head-to-head comparison of omeprazole and misoprostol [94, 113], PPIs were associated with significantly fewer drop-outs overall (RR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.52–0.97), as well as significantly fewer drop-outs due to adverse effects (RR = 0.48; 09% CI: 0.29–0.78). A1a When compared to H2-RA used for less than two months, misoprostol caused significantly more drop-outs due to abdominal pain (RR = 3.00,95% CI: 1.11,8.14) and more symptoms of diarrhea (RR 2.03, 95% CI: 1.38, 2.99). A1a There were no significant differences in drop-outs due to adverse effects (RR 1.90,95% CI: 0.77–4.67) or symptoms of abdominal pain or diarrhea between low dose H2-RAs and PPIs. Misoprostol also appears to be associated with a lower quality of life amongst chronic tNSAID users compared to PPIs [79].

Summary

Collectively these studies demonstrate that PPIs are effective for healing both gastric and duodenal NSAID induced ulcers irrespective of continued NSAID use or H. pylori status. These agents also appear to be effective for the prevention of endoscopically diagnosed NSAID induced ulcers. In high risk GI patients (secondary prophylaxis), a study from Hong Kong suggested that strategies employing a COX-2 or an NSAID + PPI show similar efficacy at reducing re-bleeding events, though both strategies were associated with important re-bleeding rates [160, 161]. A second study performed in Hong Kong showed that for very high risk GI patients, a strategy of a COX-2+ a PPI was associated with very low re-bleeding rates [162]. A1c

The appropriate choice of therapy for secondary prophylaxis against NSAID ulcer recurrence among chronic NSAID users is unclear. Currently misoprostol is the only prophylactic agent of proven benefit for the prevention of NSAID induced clinical events. However, in reality most clinicians will prescribe a PPI to heal NSAID-induced ulcers, and will continue the same agent for secondary prophylaxis. Given the results of the OMNIUM and ASTRONAUT studies, this approach may be appropriate, but a degree of caution is indicated given the limitations of these studies, and the absence of direct evidence for effectiveness of PPIs for prevention of clinical gastrointestinal events. The cost-effectiveness of PPIs for the primary or secondary prophylaxis against NSAID induced upper gastrointestinal toxicity has not been established.

Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors

Since the publication of the last edition of this book, several endoscopic studies demonstrating the safety of COX-2 inhibitors, and several important clinical outcome studies similar to the misoprostol MUCOSA study have been published. In this section we will present the latest evidence for the GI safety of COX-2 inhibitors. We will concentrate on the following COX-2s: celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib, and lumiracoxib.

NSAIDs are believed to exert their therapeutic anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects through the inhibition of inducible cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2), whereas their gastric and renal toxicities, and antiplatelet effects appear to arise from the inhibition of the constitutive COX-1 isoform [28, 29]. This COX-2 hypothesis, along with the unfavorable safety profile of standard NSAIDs, has prompted the development of newer NSAIDs with selectivity for the COX-2 isoform.

Endoscopic ulcer trials

Cyclo-oxygenase-2s vs nonselective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Seventeen studies with over 10,000 patients assessed the proportion of patients who developed endoscopic ulcers while taking a COX-2 compared to those taking a non-selective tNSAID [163–179]. There were seven studies that assessed celecoxib [163–165, 169, 175, 176, 178], three that assessed rofecoxib [166–168], two that assessed etoricoxib [173,174], five that assessed valdecoxib [170–172,177,179], and two that assessed lumiracoxib [169,175]. Some studies assessed more than one intervention [169,175].

Endoscopically detected gastro-duodenal ulcers

Thirteen studies with a total of 7839 patients showed a 74% RRR (relative risk reduction) in combined gastro-duodenal ulcers with COX-2s versus tNSAIDs (RR = 0.26; 95% CI: 0.23–0.30) (Figure 7.4) [163–174, 180]. This represented a 16% absolute risk reduction (ARR) and NNT = 6. Addition of the FDA studies did not significantly alter the results (RR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.24–0.32). A1a

Eleven studies with a total of 6726 patients compared the safety of a COX-2 to a comparator tNSAID for endoscopic gastric ulcers [163–172, 180]. The use of a COX-2 in this setting was associated with a 79% RRR in gastric ulcers (RR = 0.21; 95% CI: 0.18–0.25). This represented a 14% ARR in gastric ulcers with the use of COX-2s compared with tNSAIDs. (NNT = 7). Addition of the FDA studies did not significantly alter the results (RR = 0.26; 95% CI: 0.22–0.30). A1a

The same eleven studies also compared the proportions of duodenal ulcers that occurred while using a COX-2 versus a tNSAID [163–172, 180]. Compared to using a tNSAID, the use of a COX-2 was associated with a 66% RRR in duodenal ulcers (RR = 0.34; 95% CI: 0.25–0.45) (Figure 7.4). This represented a 3% ARR (NNT = 33). A1a Addition of the FDA studies did not significantly alter the results (RR = 0.29; 95% CI: 0.23–0.38) Keeping in mind that tNSAID related gastric ulcers were more commonly observed than duodenal ulcers, a trend was observed for greater RRR and ARR for gastric ulcers than for duodenal ulcers with COX-2s, compared to tNSAIDs (RR = 0.21 vs 0.34, ARR of 14% vs 3%). This trend was consistent when celecoxib, rofecoxib and valdecoxib were analyzed separately.

Analysis by duration

The data presented above are for any dose and duration up to six months. Subgroup analysis of these studies on the basis of duration (1–3 months and 3–6 months) did not significantly alter the results.

Analysis by cyclo-oxygenase-2

Celecoxib

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree