Medicolegal Aspects of Colon and Rectal Surgery

Alan V. Abrams

In the United States, the issue of alleged medical negligence has reached crisis proportions in many jurisdictions. Although no field of medicine is exempt from this concern, colon and rectal surgery has its own, unique areas of potential vulnerability. Practice patterns and self-education demand continuous reevaluation in order to provide the optimal care for our patients while protecting ourselves from the vicissitudes of the legal arena.

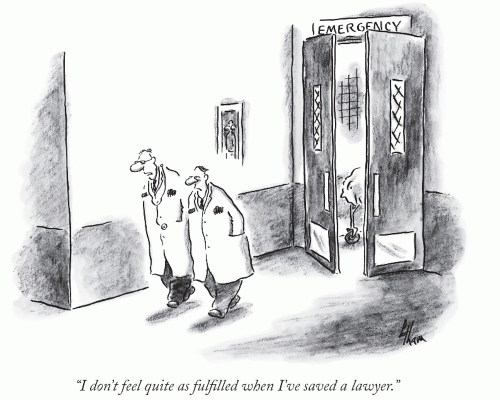

Although the penalty for medical malpractice in contemporary society is thankfully less severe than that demanded by Babylonian law, the ordeal of a malpractice suit can exact a heavy emotional, and sometimes financial, toll on the surgeon. While practicing “good medicine” is the best defense against claims of negligence, it is not always sufficient to avoid lawsuits. In fact, malpractice actions commonly arise in situations in which medical management has, by all objective criteria, conformed to the standard of care. Conversely, although many patients incur injuries during the course of treatment, studies have shown that only 1 in 10 individuals who sustain such injuries actually sue. Even in cases in which peer review evaluation concludes that negligence occurred, a patient rarely sues his or her physicians.11 It is clear that in addition to the quality of care, other factors play a role in determining whether an injured patient will commence a legal action. Consequently, the surgeon must not only understand the law as it applies to medical malpractice but also must be aware of these contributory factors in order to minimize the likelihood of litigation when such an injury occurs.

▶ HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The concept of assessing penalty for negligence resulting in injury dates back to Babylonian times, when individuals and sometimes even their families were held directly accountable. Under Hammurabi’s code of justice (c. 1750 BC), if a builder constructed a house so poorly that it collapsed and killed the son of the owner, the law allowed for the execution of the builder’s son. As judged by the quotation above, physicians were held to a similarly harsh standard. After their Babylonian captivity, the Hebrews adopted many aspects of Babylonian law but limited penalties to the practitioner himself.11 Greek civilization did not recognize professions as such, so the conceptual basis for professional negligence was lacking. Under the Roman law, however, negligent infliction of personal injury could result in compensation for the patient’s medical expenses and lost wages.

Licensing of physicians, which first occurred in the late Middle Ages, marked a major development in the evolution of personal injury law by identifying physicians as a class, separate from the rest of society by virtue of their possessing special knowledge and skill, and holding them responsible in the exercise of that skill.6

The first recorded suit for medical malpractice in English common law occurred in 1374. The United States, which adopted English common law, recorded its first case in 1794.9

▶ THE WRITTEN LAW

Medical malpractice is not a separate branch of law, but rather is a subdivision of personal injury law. In order for the plaintiff (the patient) to prevail over the defendant (the physician) in a suit for malpractice, the law requires that four elements be proven: duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages.

Duty

The surgeon has a responsibility to the patient to conform to the standard of care—that is, to exercise the skill and provide a level of medical care equivalent to that which is generally employed by the profession under similar circumstances. The duty element is usually not at issue in medical malpractice cases because once the physician undertakes care of a patient, a legally binding physician-patient relationship is established, and the physician is obligated to provide competent care. Such a relationship also exists when a physician provides coverage for a colleague or assumes responsibility for a clinic in which indigent patients are treated.1 The matter may be contested, however, if there is a question whether a valid physician-patient relationship existed.

Breach of Duty

The physician, either by omission or commission, did not conform to the standard of care. The central issue in most malpractice cases is determining what the standard of care should have been in a particular clinical setting, a matter usually argued by expert witnesses for each side. The law does not require that the physician’s care be equivalent to the best available nationally or even locally—only that it meet an accepted, usually national standard. If, as is often the case, there is more than one acceptable treatment for a condition, the physician cannot be held liable solely because the treatment mode selected results in an adverse outcome.

Causation

The physician’s failure to conform to the standard of care directly caused or contributed to the patient’s injury, a matter that is also usually the subject of expert witness testimony.

Damages

As a direct result of the physician’s failure to meet the standard of care, the patient suffered an injury that, in a civil court, is compensable by the award of monetary damages. Conversely, if the patient did not sustain an injury, he cannot recover anything, no matter what the level of care.

Unlike a criminal trial, in which the prosecution must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, a malpractice suit requires only that the plaintiff prove that his or her version of events is more likely than not, a standard commonly referred to as proof to a reasonable degree of medical probability (or certainty). The burden of proof for all of these elements lies with the plaintiff, however, and if proof of any one element is lacking, the plaintiff’s complaint of negligence cannot be sustained.

▶ THE UNWRITTEN LAWS

The most important rule to which a surgeon must adhere to prevent malpractice suits is to practice high-quality medicine. Because of the complexity of medical decision making, the law allows physicians considerable latitude in their practice by defining the standard of care as what a reasonable, rather than what the most expert practitioner would do under similar circumstances and conditions. Nevertheless, it is essential that surgeons maintain and continually update their knowledge and skills by conscientiously keeping abreast of the medical literature and regular attendance at meaningful educational conferences. Although most errors resulting in malpractice claims occur during the conduct of routine procedures rather than “index” operations,10 before undertaking a new or advanced procedure independently, the surgeon should receive adequate training and mentoring by someone competent in performing the technique. Aside from maintaining a high level of competence, however, there are many other factors that a surgeon must take into consideration to reduce the likelihood of being sued.

Patient Selection

One need not have extensive psychiatric training to realize that there are patients who, for a variety of reasons, seek to have surgery when none is indicated. Because the indications for many colorectal procedures (surgery for hemorrhoids, abdominal pain/diverticular disease, and constipation/colonic inertia) are in part subjective, such an issue is not infrequent. If there is any question about an individual’s emotional stability or motivation, the surgeon must meticulously evaluate the patient to be certain that objectively verifiable indications for surgery exist; that the patient has realistic expectations about possible outcomes, including negative ones and complications; and that all of the above is documented in the medical record. Second opinions in these situations are also valuable.

Documentation

In combination with high-quality care, good documentation is the surgeon’s strongest line of defense in malpractice litigation. Creating a medical record offers surgeons the opportunity to present their version of events contemporaneous with their occurrence. Such documentation has much more credibility in a legal setting than after-the-fact explanations and rationalizations. In a court room, if actions or discussions have not been documented, they are often considered not to have occurred.5

Notes must be legible and self-explanatory to readers other than the author. Documentation comprehensible only to the surgeon is inadequate in court, as lawyers, experts, and jurors may be unable to make sense of what the surgeon has written. Legible notes also avoid the possible additional allegation that others participating in the patient’s care misunderstood the note and, as a result, committed an error.5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree