Etiology

N (%)

Diverticulosis

227 (37.34)

Hemorrhoids

128 (21.05)

Neoplasia

72 (11.84)

Colitis

65 (10.69)

Inflammatory bowel disease

33 (5.43)

Vascular ectasias

14 (2.30)

Other colonic disease

40 (6.58)

Small-intestine disease

8 (1.32)

Unknown

21 (3.45)

Total

608 (100)

The diagnosis of OGIB was limited to upper and lower endoscopy and conventional radiography until 2001, when capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) were introduced.

Prior to these two technical advances, intraoperative enteroscopy was used to identify bleeding in the small bowel.

Indications for capsule endoscopy include OGIB, unexplained iron-deficiency anemia, and suspected Crohn’s disease, small-bowel tumors, or refractory malabsorptive syndromes. Contraindications are related to the structure and transmission signal of the capsule as well as the need for normal peristalsis for capsule efficacy.

Therefore, patients with swallowing disorders, pacemakers or implanted devices, obstruction, fistula, or stricture are not candidates for capsule endoscopy. Entrapment of the capsule occurs in 3.3 % of procedures and is associated with Crohn’s disease, radiation, and NSAID-induced strictures. Indications for DBE include a positive capsule endoscopy and a high suspicion of a small-bowel source in the setting of a normal capsule study.

DBE has the ability to perform therapies such as sclerotherapy, polypectomy, dilations, and clippings. DBE can be performed from anterograde (oral) or retrograde (rectal) approach. Patients undergoing the anterograde approach require a 6–8-h fast prior to the procedure, while those having a retrograde exam need a bowel preparation.

The diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy and DBE is 38–83 % and 58 %, respectively. Two meta-analyses comparing capsule endoscopy and DBE found similar diagnostic yields.

Clinical Presentation, Physical Exam, and Management

LGIB has many presentations reflecting the diverse pathology found in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract.

Evaluation of a patient’s hemodynamic stability upon presentation is imperative.

Tachycardia and hypotension represent acute hemorrhagic shock associated with a blood loss of more than 500 ml or 15 % of the total blood volume. These patients require two large-bore IVs or central venous access for resuscitation if peripheral access cannot be obtained. Continuous monitoring of vitals and urine output with a urinary bladder catheter is standard. Nasogastric tube (NG) placement has been recommended routinely to rule out an upper gastrointestinal source of bleeding. NG placement is a fast and inexpensive diagnostic test that, if positive (clots, coffee-ground emesis, blood), can quickly direct the workup toward identification of an upper gastrointestinal source. Upper gastrointestinal sources are seen in 11 % of patients who present with an LGIB. The NG tube can be left in and used for the bowel preparation if an urgent colonoscopy is needed.

After intravenous access has been obtained, resuscitation should start immediately. However, there are no systematic reviews, and only one randomized controlled trial evaluating the role of transfusions in gastrointestinal bleeding is available.

A Cochrane systematic review evaluating the resuscitation of trauma, burn, and surgical patients with either crystalloid or colloids found no survival benefit using colloids instead of crystalloids.

Despite the lack of large, randomized trials evaluating transfusion requirements in patients with LGIB, there is mounting evidence that limiting or eliminating transfusions leads to improved outcomes such as decreased mortality and morbidity.

The patient’s history should be taken simultaneously with the placement of intravenous access and monitors if the patient is hemodynamically unstable. Important aspects of the history that should be elucidated are given as follows: frequency, volume, color, and duration of bloody stools; comorbid conditions such as liver and cardiovascular disease; medication use such as clopidogrel, warfarin, and NSAIDs; and date of last colonoscopy/EGD.

Visual inspection of the perineum for prolapsed or thrombosed hemorrhoids, anal fissures, or masses are the first part of the anorectal exam.

After visual inspection, digital rectal exam and anoscopy are performed. It is imperative to assess the anus, anal canal, and distal rectum prior to further diagnostic tests. Anoscopy can be performed efficiently at the bedside, and if a source is found, such as internal hemorrhoids, therapy can be provided.

Laboratory studies should include a chemistry panel, complete blood count, coagulation profile, and a type and cross. Any identified coagulopathies must be corrected with appropriate factors or products. Patients with cardiovascular disease should undergo an electrocardiogram, and if it turns out to be abnormal, cardiac enzymes are obtained.

After the initial clinical evaluation and review of laboratory values, the volume of hemorrhage can be classified into one of the following three groups: (1) minor and self-limited, (2) major and self-limited, and (3) major and ongoing.

Patients with minor and self-limited lower gastrointestinal bleeding with no or minimal change in hematocrit are unlikely to be hemodynamically unstable. These patients can undergo a colonoscopy during their admission or as an outpatient.

Patients with massive, ongoing bleeding who remain hemodynamically unstable after initial resuscitation need urgent diagnosis and treatment either with angiography or with surgery.

Patients in the middle of the spectrum with major bleeding who are stable or their bleeding has ceased are the patients at the core of the diagnostic dilemma surrounding LGIB.

The most common diagnostic tests that can be employed for identifying the etiology of an LGIB are colonoscopy, angiography, CT angiography, and nuclear scintigraphy.

Colonoscopy

Colonoscopy can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The likelihood of identifying the source of bleeding with colonoscopy ranges from 45 to 95 % with the majority of studies with greater than 100 patients showing diagnostic yield rates of 89–97 %.

The timing of colonoscopy is debatable. Urgent colonoscopy has been performed within 24 h, within 12 h, and after a fast oral purge, making comparison between studies challenging.

In some studies, early colonoscopy has been associated with decreased length of stay.

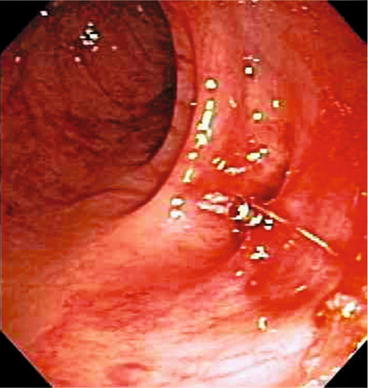

All studies evaluating urgent colonoscopy except one had patients undergo a bowel preparation, which would improve visualization and decrease the difficulty of the procedure and any endoscopic therapy. Endoscopic interventions were performed in 10–15 % of patients who underwent an urgent colonoscopy. Interventions include heater probes, argon plasma coagulation, bipolar coagulation, topical and intramucosal epinephrine, and endoclips (Fig. 24.1).

Fig. 24.1

Clip applied to bleeding diverticular vessel

Overall complication rate of colonoscopy in LGIB is 1.3 %.

Patients with major, self-limited hemorrhage who have been resuscitated should undergo a bowel preparation with a polyethylene glycol solution and colonoscopy within 24 h.

The goal of colonoscopy is to identify a source of bleeding and, if possible, treat it endoscopically. If a bleeding source is noted, the area should be marked, and the patients who rebleed require emergent surgery. Anatomic localization during endoscopy has known limitations and errors, and without a definitive mark (clip or tattoo) resection can be prone to error.

Angiography

Angiography can be both diagnostic and therapeutic (Fig. 24.2).

Fig. 24.2

Angiogram demonstrating extravasation (hemorrhage) in cecum

Angiography has both broad positivity (27–77 %) and sensitivity (40–86 %), with specificity being 100 %.

For angiography to be positive, bleeding must occur at 0.5 ml/min or faster. Small, single-institution retrospective studies have shown blood pressure less than 90, transfusion requirement greater than 5 units, and a blush within 2 min on nuclear scintigraphy to be associated with positive angiograms.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree