History

Liver transplantation has been the standard of care for almost 3 decades for patients with end-stage liver disease. The scarcity of donor organs is the major limiting factor in liver transplantation. Over 16 000 people are now waiting for a liver transplant in the USA, but only about 6000 transplants are performed every year. Roughly 10–15% of the candidates each year die of their liver disease before having the chance to undergo a transplant [1]. For those who do end up receiving a transplant from a deceased donor, the waiting time can be significant, resulting in severe debilitation. With a living-donor liver transplant (LDLT), this waiting time can be reduced, allowing the transplant to be performed before the recipient’s health deteriorates further. In areas of the world where deceased-donor transplants are not performed, due to nonexistent deceased-donor graft donation, the advantages of LDLT are even more obvious. LDLT evolved from experience gained from in situ deceased-donor hepatectomy with reduced-size and split grafts, an idea first proposed by Smith in 1969 [2].

The first LDLT was from an adult to a child using the left lobe of the liver and was performed by Raia in Brazil in 1988, but the recipient did not survive [3]. The first successful adult-to-child LDLT was performed in Australia in 1989 by Russel Strong [4]. The Chicago Group, led by Broelsch, developed the first adult-to-child LDLT program in the USA [5]. LDLT started growing rapidly following its debut and living donation of the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver has become highly successful in pediatric transplantation. With the success of LDLT in pediatric recipients, left-lobe LDLT was extended to adults; the first such transplant was reported by Makuuchi et al., but the overall success was marred by the donor organ being small for the recipient’s size [6]. The Kyoto Group in 1994 performed the first right-liver graft in a child, as the donor left-lobe arterial supply was unfavorable [7]. Fan and his team, at the University of Hong Kong, first performed adult-to-adult LDLT using the right hemiliver in 1996, with a favorable outcome [8]. Since that time, many centers have adopted the procedure, not only in Asia but in other parts of the world as well. The first adult LDLT in the USA utilizing the right lobe was reported by Wachs et al. in 1998 [9].

In the present-day scenario, LDLT accounts for almost 4% of all liver transplantation in the USA [1] and a significantly higher percentage in Asia and other parts of the world. LDLT has continued to evolve in recent years, leading to increased donor safety and better public acceptance. Short-term results and outcomes have become well described with this procedure, but longer-term results, both in donors and in recipients, need to be better defined.

Donor evaluation

The evaluation of individuals who present as possible liver donors is a crucial part of the LDLT process. A complete and thorough evaluation is important in minimizing the risks of the procedure for the potential donor and in optimizing donor safety—the underlying principle of any living-donor procedure [10]. The pre-donation evaluation of the potential donor, and characterization of the subsequent liver graft that they may yield, is also critical in ensuring a successful outcome for the recipient. The evaluation process may vary between donors, depending on whether the recipient is an adult or a pediatric patient, the size of the planned liver resection, and the individual center’s preference. But the major steps of the process remain basically the same, and can be divided into three major parts: (i) medical evaluation, (ii) surgical and radiological evaluation, and (iii) psychosocial evaluation. The potential donor should satisfy each of the three parts of this evaluation process before being considered acceptable. The evaluation process should, at the same time as being complete, not be overly cumbersome for the donor. It should be streamlined and efficient, and invasive and costly tests should be minimized and reserved for the later part of the evaluation, after the donor has passed through the initial screening process. Members of multiple teams need to be involved in the evaluation process. These should include a hepatologist, a surgeon, a psychologist, a social worker, and a transplant coordinator.

Medical evaluation

The medical evaluation of the potential donor has several goals and attempts to answer several important questions. One essential goal is to ensure that the donor does not have underlying medical problems that would significantly increase the risk associated with a general anesthetic and a major intra-abdominal procedure. This part of the evaluation is not too dissimilar from the evaluation for any individual undergoing a major general surgical procedure. The other important part of the medical evaluation serves to identify and exclude any possibility of chronic liver disease or liver dysfunction in the potential donor. This includes screening for viral pathogens that might impact on the donor’s liver function, or could potentially be significantly harmful when transmitted to the recipient.

The most useful part of the medical evaluation is the initial screening history—this may be performed by an experienced transplant coordinator (a phone interview is adequate), or else the donor can be asked to fill out a one- or two-page information sheet. Questions regarding age, height, weight, blood type (if known), past and current medical, surgical, or psychosocial problems (including a history of alcohol use), and current medication use are very helpful. Donors with a significant past medical history, obese donors, and those with significant comorbidities can be excluded with the screening history, thus avoiding a detailed and expensive evaluation process. Age is an important variable to determine at the initial screening and potential donors falling outside the center’s accepted age criteria can be excluded early. There are insufficient live-donor liver data at present to define an upper age limit for donation. Many centers have chosen 55, but potential donors have been considered by some centers up to the age of 60. Based upon data from the general surgical literature and experimental regeneration data, the limit of 60 has been considered appropriate. The lower limit of age for donation is determined by the ability to give legal consent.

After the initial screening history, basic screening labs should be performed—all of these can be performed at the laboratory that is physically closest to the potential donor. Tests to be included are complete blood count, serum electrolyte levels, liver-function tests, lipid profile, and blood type [11]. Based on the results of the screening history and screening labs, the potential donor can be brought into the transplant center for a more thorough evaluation.

The next part of the evaluation begins with a careful history and physical examination by a physician. Some feel that this should be performed by a physician who is not directly involved with the transplant team, and can therefore provide an unbiased opinion, without knowledge of the potential recipient. Individuals identified with significant underlying disorders of the cardiac, respiratory, or renal systems should be excluded from donation. Individuals with underlying risk factors for specific organ systems (e.g. age >40 and positive family history for cardiac disease) may require specialist consultation and more specific tests (e.g. echocardiogram or stress test). More detailed laboratory tests should also be performed during this part of the evaluation, including detailed viral serological evaluation (Hep C, Hep B, CMV, EBV, and HIV), screening for thrombophilia disorders (protein C, protein S, antithrombin III, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutation, and cardiolipin/antiphospholipids antibodies), and tests to exclude underlying chronic liver diseases (serum transferrin saturation, ferritin, α 1-antitrypsin antinuclear antibody, smooth-muscle antibody, and antimitochondrial antibody). Other tests that should be performed at this initial visit include electrocardiography, chest radiography, and pulmonary-function tests (if there is a history of smoking or asthma). Additional laboratory tests and imaging studies may be needed based on abnormalities identified in the history and the physical.

Special issues in the medical evaluation

Donor obesity

Body mass index (BMI) is a useful parameter to measure in the donor as a number of studies have shown a good correlation between obesity (BMI >28 kg/m2) and hepatic steatosis. One study suggested that 78% of potential donors with a BMI >28 kg/m2 had >10% steatosis on liver biopsy [12]. However, not all studies have shown this degree of correlation, and mild degrees of obesity may not be associated with significant steatosis in many cases. In such cases, a more direct evaluation of the liver parenchyma, usually with a liver biopsy, may be necessary to rule out the possibility of hepatic steatosis.

An additional problem with the use of obese donors is the potential for increased surgical risk in the donor. Studies from the general surgery literature suggest an increased incidence of surgical complications such as bleeding and wound problems in obese individuals. Obesity is also a risk factor for underlying cardiovascular problems, which could lead to an increased chance of medical complications post-transplant.

Because of these risk factors, most obese individuals will not be suitable donors. The exact upper limit of BMI is at the discretion of the individual center. Certainly a BMI >35 would be a contraindication for virtually all centers. Many centers will exclude donors with BMI >30, but others will selectively evaluate these donors, and routinely perform a liver biopsy on them to rule out the possibility of liver steatosis [13–14].

Hepatitis B core-antibody-positive donors

The use of donors who are hepatitis B virus (HBV) core-antibody-positive involves consideration of two factors: risk to the donor and potential risk of transmission to the recipient [15]. Donors who are HBV core-positive but surface-antigen-negative have had previous exposure to HBV but do not have active infection. The proportion of potential donors that are core-positive will vary depending on the geographic area. For example, in parts of Asia more than 50% of potential donors may fall into this category. The majority of these donors will have completely normal livers, and studies from centers in Asia have shown that the risk to them is no higher than that to non-HBV core-antibody-positive donors. However, since these donors have had previous HBV infection, a liver biopsy should be performed during the evaluation process to rule out the possibility of hepatic inflammation or fibrosis.

With regard to the recipient, the issues are no different than those for a deceased donor who is core-positive. A recipients who has not been exposed to HBV in the past can potentially acquire primary HBV infection after transplantation from these donors. However, this risk can be minimized or virtually eliminated by the use of appropriate HBV prophylaxis.

Evaluation for thrombophilia

Deep-venous thrombosis (DVT) with subsequent pulmonary embolism represents a serious postoperative complication that can be potentially life-threatening. Several cases of pulmonary embolism have been reported, with at least one or two cases of mortality due to this complication. Known risk factors for thromboembolic complications include obesity, use of oral hormone therapy, older age, smoking, positive family history, and an identified underlying procoagulation disorder. These risk factors should be addressed during the evaluation process, which should include screening tests to identify a procoagulation disorder. Tests should check for protein C and S deficiency, the presence of antiphospholipid or anticardiolipin antibodies, and factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutations.

Surgical evaluation

This part of the evaluation is concerned with determining whether the anatomy of the liver is suitable for donation. A number of tests can be performed here, but essentially one wants to obtain information about the vascular anatomy, the liver volume (both the volume to be removed and the volume to be left behind), and the presence of any abnormalities of the hepatic parenchyma.

Vascular anatomy

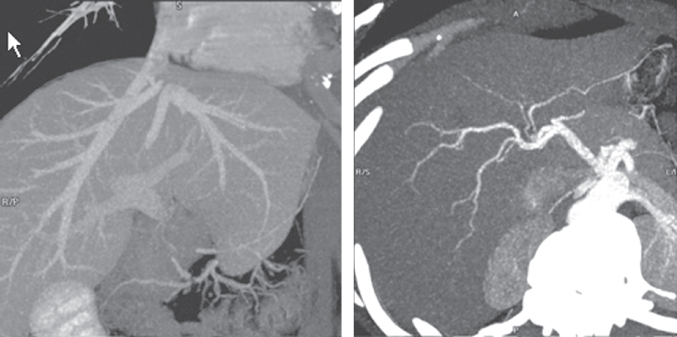

Evaluation of the vascular anatomy pre-donation includes imaging of the hepatic artery, portal vein, and hepatic veins. Most centers have abandoned the use of invasive tests such as angiography, and routinely use computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with three-dimensional reconstructions as a single test [16–17]. While some vascular variations may preclude donation, most can be handled with vascular-reconstruction techniques. However, preoperative knowledge of these variations is important for planning the operative procedure and performing the operative dissection. Possible vascular variations include a replaced or accessory left (or right) hepatic artery, trifurcation of the main portal vein, and accessory hepatic veins. Depending on which portion of the liver is to be removed, these anatomical variations may either have no impact or significantly complicate surgery.

The biliary anatomy may be difficult to evaluate accurately preoperatively. Some centers routinely perform magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as part of the evaluation process. The latter is an invasive test, while the former may not provide the degree of accuracy and clarity required to be of value. As a result, many centers choose to perform an intraoperative cholangiogram rather than preoperative biliary imaging. However, ongoing improvements in imaging modalities may soon allow for preoperative noninvasive imaging that is equivalent to the intraoperative cholangiogram with regards to its detail and clarity.

Liver volume

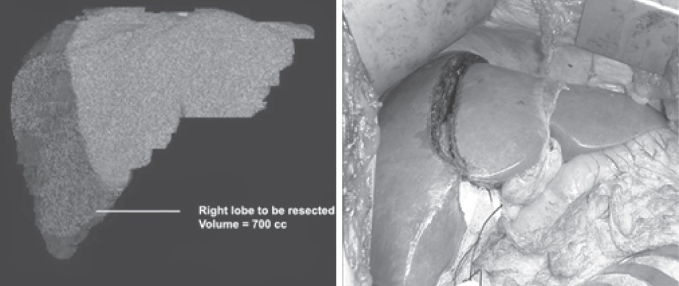

Two important questions need to be answered with regard to liver volume during the evaluation process: (i) Is the volume of the graft to be transplanted of adequate size for the recipient?; and (ii) Is the volume of liver to be left behind in the donor of sufficient size to prevent acute liver failure? While the donor’s height and weight may provide a crude estimate of liver volume, this will not be very accurate. This is especially true for the left lateral segment, which can be quite variable in size. Again, a CT or MRI scan can provide a good estimate of the liver volume. It is often helpful for the surgeon to work closely with the radiologist in making the planned line of liver transection, in order to provide the most accurate assessment of graft volume (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

Figure 3.1 Vascular anatomy, including the hepatic veins, portal vein, and hepatic artery, can be determined with a single noninvasive test such as a CT scan with contrast

Figure 3.2 Determination of the volume of liver to be resected is an important component of the preoperative surgical evaluation and usually correlates well with intraoperative findings

For a pediatric recipient, the main issue is not usually whether the liver volume might be too small, but rather if it might be too large; this can lead to problems with closure of the abdomen in the recipient. Usually the graft-weight-to-recipient-weight (GW/RW) ratio should not exceed 5%. The left lateral segment is used most commonly for these recipients, and removal of this small portion of the liver should not be a concern with regard to adequate residual volume in the donor. For an adult recipient, however, the volume of the graft and residual volume are more critical issues. Most centers currently use the right lobe for adult recipients. Preoperative evaluation should include measurement of the graft liver volume, to ensure that it is not too small for the recipient. Most centers attempt to keep the GW/RW ratio greater than 0.8, or an estimate of graft weight as a percentage of standard liver mass above 40%. Grafts that are smaller than this may be associated with poorer outcome in the recipient, often due to problems such as small-for-size syndrome.

With regard to residual volume in the donor, an important part of the evaluation process is to make sure that the donor is not left with too small a liver volume. Liver failure has been reported post-donation, with at least two donors in the USA having required an urgent liver transplant because of liver failure after donation. The planned resection should not exceed 70% of the total liver volume; that is, the donor should be left with at least 30% of the measured total liver volume.

Liver parenchyma

Evaluation of the liver parenchyma pre-donation is best done with a liver biopsy. The role and utilization of liver biopsy, however, varies from center to center, and remains controversial. Some centers routinely biopsy all potential donors, while others biopsy only on a selective basis [18–19]. The main purpose of the liver biopsy is to assess for the presence and degree of steatosis and rule out any possibility of underlying chronic liver disease. Steatosis may be more common in donors with a history of alcohol use, elevated triglyceride levels, higher BMI, or abnormal appearance on CT imaging. Some centers use these criteria to selectively biopsy the donors. Unfortunately, even with these selection criteria, some cases of steatosis may not be identified pre-donation. Additionally, other parenchymal abnormalities that are occult may be difficult to identify using these criteria, and hence some centers recommend routine biopsy for all potential donors. Liver biopsy represents an invasive test, with a potential risk for complications such as bleeding. However, the risk of complications is generally very low, and may be outweighed by the benefit of identifying a potential donor with significant occult liver disease that would preclude donation. Additional studies are needed to better define the role of liver biopsy.

Liver-biopsy results that would preclude donation include fibrosis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), steatosis >10–20% (for right-lobe liver donors), and histological abnormalities such as inflammatory changes. There are some data to suggest that steatosis identified on a pre-donation biopsy can be reversed with a program of dieting and exercise, and rebiopsy in this situation may show the potential donor to be suitable [20].

Psychosocial evaluation

This part of the evaluation assesses the donor’s mental fitness and willingness to donate, ensuring that consent is obtained in a voluntary manner, with the absence of coercion. The formal part of this evaluation should be conducted by a health-care professional such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, or other mental-health specialist. There are several components to this part of the evaluation, but basically the following issues should be addressed [21–23]:

Recipient evaluation

Evaluation of the recipient is similar to that in deceased-donor transplantation and all potential recipients should be listed for deceased-donor liver transplant (DDLT). Particular attention needs to be paid to the degree of underlying portal hypertension, patency of portal and hepatic vasculature, presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and cardiac and pulmonary status. Size-matching between the potential donor and the intended recipient is also an essential component of the evaluation.

Pediatric recipients

Introduction

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree