Fig. 11.1

Estimated stomach cancer incidence worldwide in 2012

The etiology of gastric cancer is multifactorial. Previous studies show that adequate intake of fresh fruits and vegetables decreases the risk of gastric cancer, and excess intake of salt increases the risk [3]. Also, helicobacter pylori infection is strongly associated with the development of gastric cancer [4].

The liver is the most frequent site of distant metastases from colorectal cancer with a rate of 17–29 % [5, 6]. In these cases, liver resection is widely accepted as a treatment and potential cure. There are some differences between colorectal liver metastases and gastric liver metastases with regard to liver resection (Table 11.1). In patients with gastric cancer, the rate of synchronous and metachronous liver metastases was reported to be 3.5–11.1 %. Most patients with liver metastases from gastric cancer are multiple bilobar diseases accompanied with simultaneous peritoneal dissemination, widespread lymph node metastases, and direct invasion to adjacent structures [7–9]. In a previous RCT for advanced gastric cancer, 44 % of patients with liver metastases were included in the study [10].

Table 11.1

Clinical differences between GLM and CLM

GLM | CLM | |

|---|---|---|

Efficacy of liver resection | Unknown (%) | Established (%) |

Incidence of liver metastases | 4.50 | 23–29 |

Rate of liver resection | <20 | 20–40 |

5-year survival after liver resection | 20–30 | 30–50 |

11.2 Natural History

Liver metastasis is defined as a non-curative factor in patients with gastric cancer in classifications by both the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association and the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging [11, 12] (Tables 11.2 and 11.3). The prognosis for gastric cancer patients with liver metastases is poor, with a 6-month survival rate of 20–50 % [7, 8, 13]. A previous RCT demonstrated the natural history of patients with advanced gastric cancer including liver metastases, with a median survival time of 2–4 months (Table 11.4) [14–16]. However, systemic chemotherapy can prolong overall survival.

Table 11.2

TNM classification of gastric tumors

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial tumor without invasion of the lamina propria |

T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa |

T1a | Tumor invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

T1b | Tumor invades submucosa |

T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

T3 | Tumor penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures.c,d |

T4 | Tumor invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) or adjacent structures.c,d |

T4a | Tumor invades serosa (visceral peritoneum) |

T4b | Tumor invades adjacent structures |

NX | Regional lymph node(s) cannot be assessed |

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis.b |

N1 | Metastases in 1–2 regional lymph nodes |

N2 | Metastases in 3–6 regional lymph nodes |

N3 | Metastases in ≥7 regional lymph nodes |

N3a | Metastases in 7–15 regional lymph nodes |

N3b | Metastases in ≥16 regional lymph nodes |

M0 | No distant metastasis |

M1 | Distant metastasis |

Table 11.3

Stage grouping

Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

IA | T1 | N0 | M0 |

IB | T2 | N0 | M0 |

T1 | N1 | M0 | |

IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

T2 | N1 | M0 | |

T1 | N2 | M0 | |

IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 |

T3 | N1 | M0 | |

T2 | N2 | M0 | |

T1 | N3 | M0 | |

IIIA | T4a | N1 | M0 |

T3 | N2 | M0 | |

T2 | N3 | M0 | |

IIIB | T4b | N0 | M0 |

T4b | N1 | M0 | |

T4a | N2 | M0 | |

T3 | N3 | M0 | |

IIIC | T4b | N2 | M0 |

T4b | N3 | M0 | |

T4a | N3 | M0 | |

IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

Table 11.4

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing best supportive care (BSC) in management of advanced gastric cancer

Patients | RR | MST(months) | P-value | Author | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

FAMTX | 30 | 50 | 9 | P < 0.01 | Murad (1993) |

BSC | 10 | – | 2 | ||

ELF | 10 | 30 | 10 | P < 0.02 | Glimelius (1994) |

BSC | 8 | – | 4 | ||

FEMTX | 21 | 29 | 12.3 | P < 0.01 | Pyrhonen (1995) |

BSC | 20 | – | 3.1 |

11.3 Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is crucial because of the possibility of early metastasis to the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneal dissemination. Most patients in Western countries are diagnosed with inoperable advanced disease requiring palliative treatment. A screening system has been developed in Japan and has shown that early diagnosis is possible [17]. Currently, synchronous liver metastases can be detected at a rate of 2.2–4.8 % [18–20]. Upper endoscopy is the most sensitive and specific method for diagnosing gastric cancer compared to other diagnostic strategies such as barium studies. During endoscopy, any suspicious lesion can be biopsied easily and a final diagnosis can be done. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CE-CT) should be routinely performed for staging, especially for liver metastases and lymph node metastases (Fig. 11.2). Gross appearance of GLM as well as radiological finding is similar with other primary or metastatic adenocarcinoma (Fig. 11.3). Lymph node metastases can be detected by CT and larger lymph nodes are highly related to metastases. Peritoneal metastases and liver metastases smaller than 5 mm are frequently missed by CT even with multidirector row CT [21]. The depth of tumor invasion is not accurately assessed with CT. Staging laparoscopy can detect radiographically occult peritoneal metastases and reduce the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with laparotomy [22]. The use of 18-fluorodexyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) CT can help detect occult extrahepatic metastases; however, the detection rate of diffuse gastric cancers is very low [23]. Smyth et al. reported that FDG-PET/CT identified metastatic lesions in approximately 10 % of patients with locally advanced gastric cancer [24]. The current gold standard in preoperative diagnosis focusing on liver metastases from gastric cancer (GLM) is CE-CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using a gadolinium-based contrast agent. A novel imaging technique, gadolinium ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced MRI (EOB-MRI), has been developed for identifying liver neoplasms. This technique enables not only a dynamic study evaluating tumor vascularity but also liver-specific imaging with the contrast agent taken up by the liver cells. EOB-MRI is therefore considered a more highly sensitive imaging modality over MRI and CE-CT for demonstrating and characterizing liver tumors.

Fig. 11.2

Contrast-enhanced axial CT reveals a hypovascular tumor in segment 5 and 8 of the liver

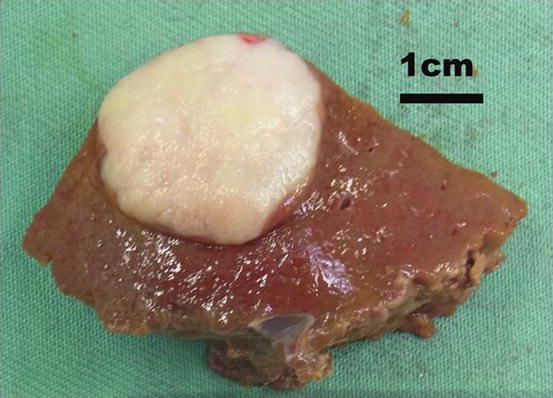

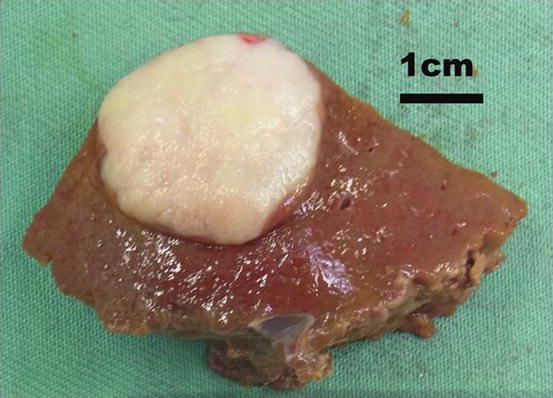

Fig. 11.3

Gross appearance of GLM

11.4 Treatment

11.4.1 Treatment of the Primary Lesion with Synchronous Liver Metastases

Most cases of liver metastases from gastric cancer are considered to be an incurable advanced disease and are treated with palliative chemotherapy. The indication for gastrectomy in patients with incurable distant metastases should be determined after consideration of individual performance status and the surgical risk involved. In a particular patient with symptomatic gastric cancer such as bleeding or obstruction, gastrectomy can be indicated with the aim of palliation. In general, palliative systemic chemotherapy is indicated for liver metastases from gastric cancer.

11.5 Palliative Systemic Chemotherapy

There are different backgrounds and treatments for resectable gastric cancer between Eastern and Western countries [25–27]. However, the standard treatment for metastatic gastric cancer including most gastric liver metastases is systemic chemotherapy. Most liver metastases from gastric cancer are multiple and disseminated diseases with other non-curable factors such as peritoneal dissemination or extensive lymph node metastases [28]. The benefit of palliative chemotherapy over best supportive care for advanced gastric cancer has been demonstrated in RCTs [16, 29]. Systematic review and meta-analysis showed that systemic chemotherapy had a survival benefit compared with best supportive care in patients with advanced gastric cancer [30]. To date, a large number of chemotherapy regimens have been tested in randomized studies, including patients with liver metastases from gastric cancer. Due to the differences of tolerability to chemotherapy, standard chemotherapeutic treatments for advanced gastric cancer including liver metastases is heterogeneous throughout the world. There is no international consensus regarding which chemotherapy regimen should be used first.

In Western countries, many chemotherapy regimens are effective in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer [31–34], and to date, combination therapy is superior to single-agent chemotherapy. The current standard regimen in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer is combination therapy with ECF (epirubicin, cisplatin, and infused 5-FU) [35] (Table 11.5). In Japan, the current first-line chemotherapy regimen for metastatic gastric cancer (mGC) is a combination therapy of fluoropyrimidine plus a platinum compound [36, 37] (Table 11.6). More recent phase III studies have focused on the benefit of adding a targeted therapy to XP therapy (capecitabine plus cisplatin) [38, 39]. A recent study identified human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) as an important biomarker for gastric cancer prognosis. In a recent worldwide RCT (ToGA study), the addition of trastuzumab to XP improved survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer or gastroesophageal junction cancer compared with XP alone [38]. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy is considered a new standard option for patients with HER2-positive mGC, although the HER2 status should be tested in liver metastases as well as in the primary lesion due to the heterogeneity of HER2 [40].

Table 11.5

RCTs for advanced gastric cancer in Western countries

RCT | Regimen | Number of patients | RR (%) | MST(months) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

EORTC (1991) | FAM | 103 | 9 | 7.2 | 0.04 |

FAMTX | 105 | 41 | 10.5 | ||

Webb et al. [32] | FAMTX | 130 | 21 | 5.7 | 0.0009 |

ECF | 126 | 45 | 8.9 | ||

EORTC (2000) | FAMTX | 133 | 12 | 6.7 | NS |

ELF | 132 | 9 | 7.2 | ||

FP | 134 | 20 | 7.2 | ||

V325 (2006) | DCF | 221 | 38.7 | 9.2 | 0.02 |

FP | 224 | 23.2 | 8.6 |

Table 11.6

RCTs for advanced gastric cancer in Japan

RCT | Regimen | Number of patients | RR | PFS | OS | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

SPIRITS | S1 | 150 | 31 | 4 | 11 | |

S1 + CDDP | 148 | 54 | 6 | 13 | 0.0366 | |

JCOG9912 | 5FU | 234 | 9 | 2.9 | 10.8 | |

Irinotecan + CDDP | 236 | 38 | 4.8 | 12.3 | 0.055 | |

S-1 | 234 | 28 | 4.2 | 11.4 | 0.034 | |

GC0301/TOP-002 | S-1 | 160 | 27 | 3.6 | 10.5 | |

S-1+ irinotecan | 155 | 42 | 4.5 | 12.8 | NS |

11.6 Surgical Treatment of Liver Metastases of Gastric Cancer

Reports on liver resection for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine metastases (NCNN) from Western institutions include only very small numbers of patients with GLM (2–4 %) (Table 11.7). In contrast, liver resection of GLM comprises most cases of liver resection for NCNN in Japan. There is no prospective study to evaluate the efficacy of surgical treatment of GLM due to the small number of cases. Ochiai et al. reported the first case series to identify the predictive factors for GLM after liver resection [41]; however, to date only a limited number of retrospective analyses exist. Takemura et al. reported a retrospective analysis of the largest number of cases of GLM with liver resection (n = 64) from a single center in Japan, with an overall survival rate after liver resection of 37 %. Adam et al. also reported on a series of 64 cases of surgically treated GLM, which was a subset of 1,452 patients with non-colorectal liver metastases from 41 institutions [42]. Elias et al. reported disappointing results with a 3-year survival rate of lower than 20 % [43]. However, conclusions cannot be drawn from the retrospective analysis of less than 100 cases. Therefore, the significance of liver resection for liver metastases from gastric cancer remains controversial due to the lack of evidence. Some consider that liver metastases from gastric cancer represent a systemic disease and surgery has no role in its treatment because the results of liver resections are still discouraging. In contrast to colorectal liver metastases, liver-limited metastases are a rare condition in patients with GLM, most of which have an accompanying extrahepatic disease such as peritoneal dissemination or extensive lymph node metastases. However, a retrospective study of a small number of highly selected cases reported that long-term survivors encouraged the surgical resection for gastric liver metastases.

Table 11.7

Rate of GLM undergoing liver resection for metastatic non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine tumors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree