Fig. 4.1

Illustration of the larynx, demonstrating the supraglottic, glottis, and subglottic regions with major anatomic structures

Laryngeal cancer is staged clinically, based on the extent of disease at the initial presentation prior to any treatment. The American Joint Committee on Cancer has agreed to designate staging based on the tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification system [33]. Based on this staging system, any laryngeal cancer that demonstrates evidence of distant metastases is automatically classified as a Stage IV(C) tumor. Lastly, since squamous cell carcinomas compose approximately 90–95 % of all laryngeal cancers, the focus on the presentation, diagnosis, and management will be directed toward that form of pathology.

4.2.2 Clinical Presentation and Spread of Primary Laryngeal Cancer

The presenting symptoms of laryngeal cancer depend on the anatomic region that is primarily involved. In glottis cancer, the spectrum of symptoms includes persistent hoarseness, dysphagia, chronic cough, hemoptysis, and referred otalgia. Primary subglottic cancer or extension of disease into the subglottic region can present with stridor or dyspnea on exertion. Lastly, primary supraglottic cancer or extension is often discovered late in the disease process, and patients may present with palpable lymph nodes or airway obstruction.

Locoregionally, laryngeal cancer can spread via lymphatic channels or direct extension. Notably, the supraglottic region has the richest lymphatic supply compared to the glottis, which has little to no lymphatic circulation. From the supraglottic region, local metastasis can proceed to the upper and lower deep cervical lymph nodes. Regarding the subglottic region, although there is very limited lymphatic exposure, metastases can spread to the paratracheal lymph nodes or to the deep cervical lymph nodes as well. Thus, for glottis cancer to metastasize regionally, there must be either direct stromal extension into surrounding tissues or extension of the tumor to the supraglottic and subglottic regions.

Metastases to distant sites, including the liver, occur through hematogenous channels. In laryngeal cancer, tumor cell access to the hematogenous circulation can be achieved through tumor angiogenesis or extension into existing vasculature. Circulatory access can also be achieved indirectly via the lymphatic system, where the deep cervical glands drain to the jugular lymph trunk on the right and the thoracic duct on the left, both of which eventually drain at the junction of the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein.

4.2.3 Risk Factors and Clinical Presentation of Distant Metastases to the Liver

When considering possible sites of distant metastasis, the lungs, liver, and bone are the most common targets for hematogenous tumor spread, and the mediastinum represents the most common site for distant lymphatic tumor spread. To date, there have been no studies evaluating the distinct risk factors for distant metastasis of laryngeal cancer to the liver specifically. In a large retrospective series of over 1,900 patients evaluating the risk factors for distant metastasis in HNSCC, it was found that poor locoregional control, higher N stage, and local extension were significantly associated with a higher risk for distant metastasis, which was consistent with other studies evaluating this property of laryngeal cancer [15, 34]. In other large studies evaluating distant metastasis, delayed regional metastasis, and the role of extracapsular tumor spread for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer, the results confirmed the aforementioned risk factors for distant metastasis and also demonstrated that extracapsular extension in metastatic lymph nodes significantly increased the risk for distant metastases [20, 35]. Additionally, age and site of primary cancer have both been associated with the risk for distant metastases in HNSCC [18]. Lastly, in a smaller series of 650 patients evaluating the factors associated with liver metastases specifically from HNSCC, the same risk factors noted for general distant metastasis were also seen [29].

Although liver metastasis is infrequently associated with advanced laryngeal cancer, its clinical presentation is often indolent during the course of disease. If symptoms are present, they will usually be nonspecific initially including anorexia, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain. Liver-specific symptoms generally will not be present until the disease process has greatly advanced potentially resulting in acute liver failure or cirrhosis . However, during the natural course of the disease, other symptoms can be utilized to alert the physician that either liver metastases are present or a patient is at high risk for liver metastasis. As stated above, advanced locoregional disease including regional lymph node metastasis is strongly associated with the risk for distant metastasis, and thus enlarged deep cervical lymph nodes should be worrisome for distant metastases. Additionally, pulmonary metastases are identified in a significantly greater proportion of patients with liver metastases as compared to those without [29]. Although also nonspecific, symptoms of metastases to the lung include cough, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and chest pain.

4.2.4 Course and Prognosis of Advanced Laryngeal Cancer with Distant Metastasis

Generally speaking, distant metastatic disease from head and neck cancer is incurable , and prognosis is often variable depending on patient comorbidities and tumor pathology. The median time from diagnosis of distant metastases to death ranges from 1 to 12 months, with approximately 88 % of patients dying by 1 year from diagnosis[36–38]. As seen above, advanced locoregional disease often precedes distant metastasis, which can present as worsening dyspnea, airway obstruction, and hoarseness. Progressive nodal disease can result in lymphatic metastasis to the mediastinum, which often presents with similar symptoms as locoregional disease alone, until there is significant involvement of mediastinal structures. As metastases proceed downstream via hematogenous channels to the lungs, liver, and thoracic bones predominately, symptoms remain relatively nonspecific until the disease burden becomes high enough to result in organ failure. The end result of distant metastasis of laryngeal cancer to the liver can either be acute liver failure or decompensated chronic liver failure, which often presents with abdominal pain, ascites, jaundice, confusion, and easy bruising. However, since the majority of patients with laryngeal cancer do not suffer from distant metastatic disease, the end result in the natural course of laryngeal cancer is often related to locoregional disease causing comprise of the airway, requiring immediate and early intervention.

4.3 Diagnosis

4.3.1 Initial Workup of Primary Laryngeal Cancer

When a patient presents with symptoms concerning for laryngeal cancer, he/she undergoes an initial diagnostic evaluation including a thorough physical exam of the head and neck, flexible laryngoscopy to directly visualize the potential lesion, and, under general anesthesia, direct laryngoscopy with biopsy of the lesion for histologic confirmation (Figs. 4.2 and 4.3). Once the diagnosis of laryngeal cancer is confirmed, the patient generally receives further testing for lymphatic and distant metastases at initial presentation. First, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck is generally standard of care for evaluating the extensions of the lesion and detecting locoregional lymphatic spread for staging purposes (Figs. 4.2 and 4.3). Though MRI is superior to CT in providing clearer soft tissue definition for tumor extensions, it is inferior in accurately detecting nodal metastases; thus, MRI and CT be viewed as complementary to one another for evaluation of burden of disease [39]. Although plain chest radiography was historically used to detect pulmonary metastases, it has subsequently been replaced by chest computed tomography (CT) given its higher sensitivity [36, 40]. Other traditional tests for distant metastases include bone scintigraphy and liver function tests for bone and liver metastases, respectively. However, both of these tests lack specificity for metastatic disease processes and thus are relatively unreliable tests for accurately demonstrating distant metastases. Also, given the minimally invasive and inexpensive approach of ultrasonography for detecting liver metastases, it is still generally performed even though it has a lower sensitivity than other imaging modalities [36]. Additionally, abdominal CT may also be used to detect metastases to the liver as well.

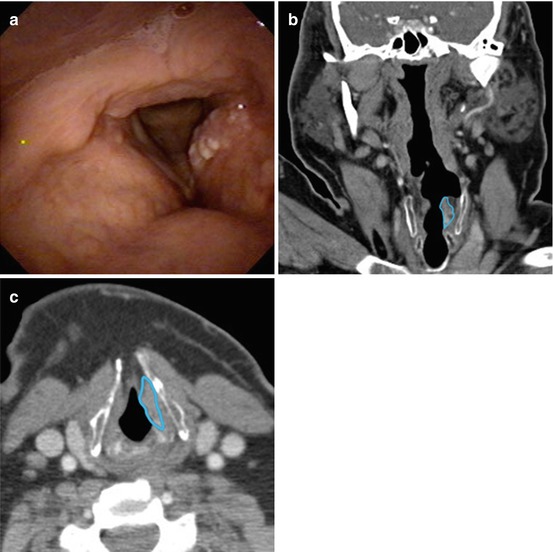

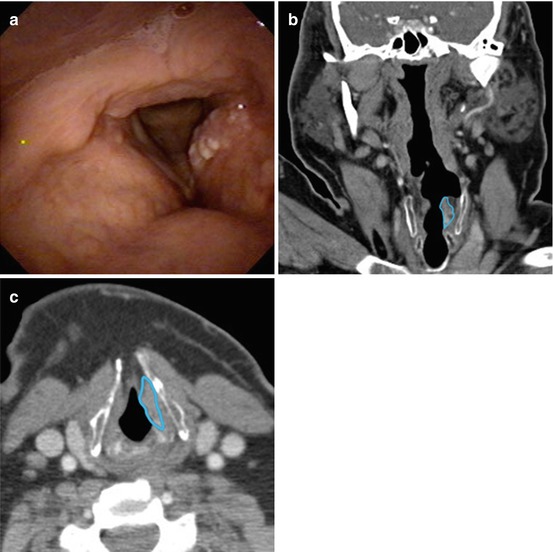

Fig. 4.2

Stage II squamous cell carcinoma of the left true vocal fold and false vocal fold (glottis cancer). (a) Laryngoscopic view of the glottis cancer using a flexible, fiberoptic laryngoscope with anterior aspect at the bottom edge of the image and posterior aspect at the top edge of the image. (b) Computed tomography (CT) scan (coronal slice) demonstrating glottis cancer, outlined in blue. (c) CT scan (axial slice) demonstrating glottis cancer, outline in blue

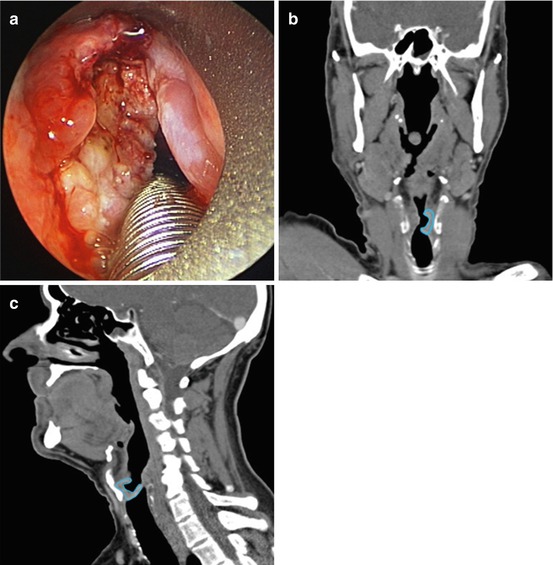

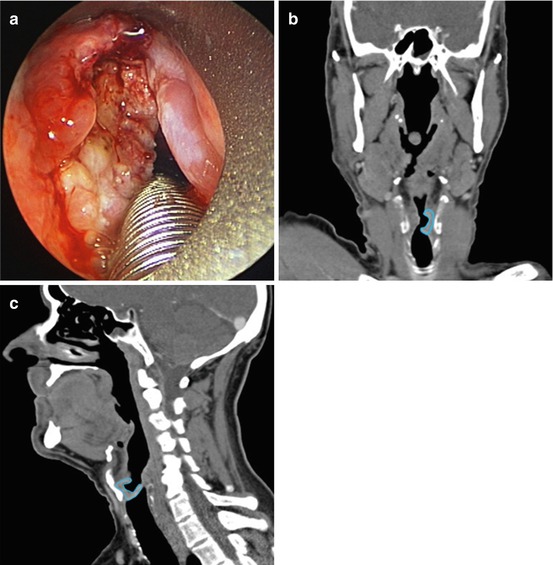

Fig. 4.3

Stage III squamous cell carcinoma of the left transglottic larynx (primary glottis cancer with either supraglottic or subglottic extension or evidence of both). (a) Intraoperative view of the transglottic cancer using a rigid laryngoscope with the posterior aspect at the bottom edge of the image and anterior aspect at the top edge of the image. (b) Computed tomography (CT) scan (coronal slice) demonstrating transglottic cancer, outline in blue. (c) CT scan (sagittal slice) demonstrating transglottic cancer, outline in blue

4.3.2 Screening for Liver Metastases

The dogma for an ideal screening modality is that it should be inexpensive, appropriately sensitive, and noninvasive. Although liver function tests (LFTs ) are commonly obtained at the initial consultation visit for HNSCC, there is minimal data supporting routine usage of LFTs for metastatic screening. First, given the higher incidence of heavy alcohol use in the head and neck cancer population, elevated LFTs may be unreliable in metastatic surveillance due to concomitant liver disease falsely elevating liver enzymes [38, 41]. In a recent update on the use of LFTs as a screening modality for laryngeal cancer, LFTs were demonstrated to lack adequate sensitivity and specificity in reliably identifying patients with liver metastases from HNSCC [29]. Overall sensitivity for all LFTs was found to be very low at 45 %, and specificity was noted to be at 75 % [29] (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of liver function tests

ALT | AST | LDH | AP | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sensitivity (95 % CI) | 0 (0–16.84) | 10.0 (1.23–31.70) | 30.0 (11.89–54.28) | 20.0 (5.73–43.66) | 45.0 (23.06–68.47) |

Specificity (95 % CI) | 94.33 (92.24–96.0) | 89.92 (87.31–92.15) | 91.97 (89.58–93.96) | 88.03 (85.25–90.45) | 74.96 (71.40–78.29) |

PPV (95 % CI) | 0 (0–9.74) | 3.03 (0.37–10.52) | 10.53 (3.96–21.52) | 5.0 (1.38–12.31) | 5.36 (2.48–9.93) |

NPV (95 % CI) | 96.77 (95.05–98.02) | 96.94 (95.21–98.18) | 97.65 (96.10–98.71) | 97.22 (95.52–98.40) | 97.74 (95.99–98.87) |

Given these findings, alternative screening modalities have been investigated to determine a more sensitive surveillance method for liver metastases including ultrasound, CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET). Ultrasonography is usually the initial method of choice given that it is relatively inexpensive, generally accurate in detecting liver metastases, and limits unnecessary radiation exposure [25]. Although CT and MRI are more sensitive in detecting metastatic lesions to the liver, they are also comparatively expensive and expose that patient to further radiation [25, 42]. Of note, recent technical advancements have further increased the accuracy of these radiographic methods, including multi-detector row CT and diffusion-weighted MRI, but further studies must be done to evaluate their role as screening tools [43]. Lastly, F-18-fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET ) is a functional modality that has been shown to be useful in the initial staging of HNSCC and detection of distant metastases before and after potential therapeutic interventions [44, 45]. Although PET studies are useful in detecting occult metastases, they must be combined with traditional radiographic imaging, such as CT, in order to accurately locate the metastatic lesion. Through analysis of all modalities, it has been seen that screening for distant metastases in advanced HNSCC patients is best performed using FDG-PET combined with CT for high-risk patients [43, 46].

Lastly, the timing of screening for distant metastases is twofold. First, evaluation for distant metastases occurs at the initial consultation visit as part of the initial staging process, which guides providers in forming a treatment plan and providing a prognosis. Depending on availability and cost to the patient, practitioners will employ the imaging modalities described above to determine the presence of distant metastases at presentation. Secondly, regarding metastatic surveillance during the course of disease, routine screening of asymptomatic patients is generally of little clinical value since treatment for distant metastases has no curative intent and palliative interventions are unnecessary when patients remain asymptomatic.

4.4 Treatment

4.4.1 Local Management of Advanced Laryngeal Cancer in the Setting of Distant Metastases

Generally speaking, distant metastatic disease in the setting of laryngeal cancer is incurable. With this notion in mind, principles of oncologic management dictate that interventions with curative intentions should be reserved for those patients with only locoregional disease, whereas palliative interventions and supportive care are intended for patients with evidence of distant, metastatic spread. Given the focus of this chapter, the discussion of treatment will focus on the nuances of palliative interventions for advanced laryngeal cancer in the setting of concomitant liver metastases. Aggressive interventions with curative intent include surgical resection, radiation therapy, or chemoradiotherapy . In regard to the management of locoregional disease from laryngeal cancer, patients with particularly bulky or symptomatic tumors may undergo relatively aggressive interventions with palliative intent including surgical tumor debulking, radiation therapy doses up to 70 Gy, and, very rarely, a total laryngectomy. However, it is important for the patient to be aware that these interventions are not of a curative nature, but instead primarily for improvements in quality of life such as pain control and improvement in dysphagia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree