Stage I disease confined to the ovary

Stage II disease confined to the pelvis

Stage III peritoneal seeding in the abdominal cavity including pancreatic, diaphragmatic, and bowel invasion

Stage IV hepatic parenchymal metastasis

Ovarian cancer spreads by direct extension and intraperitoneal seeding, via lymphatic pathways or hematogenous spread. The most common route of spread is via intraperitoneal seeding as the tumor cells shed and circulate in the peritoneal fluid. Approximately 70 % of patients are found to have peritoneal metastases at the time of staging laparotomy.

In contrast hematogenous spread is the least common form of ovarian metastasis and is rarely present at the time of diagnosis. The most common sites for this form of dissemination are the colon, liver, intestine, and lung in 50, 48, 44, and 34 % of patients, respectively [19].

Initial investigations include physical examination, ultrasound scan of the pelvis, and CT chest abdomen pelvis [12]. MRI has been used more recently in the detection of early peritoneal carcinomatosis and PET CT when investigating recurrent disease [16].

7.2.2 Treatment

Cytoreductive surgery to minimize residual tumor followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy is the standard treatment for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer [18].

Management first requires surgical staging in the form of staging laparotomy, and at this time approximately 30 % of patients are upstaged [20].

Total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy alone are performed for stage I disease. Cytoreductive surgery is carried out for patients with stage II–IV disease [20–22, 23]. This is followed by systemic platinum-based chemotherapy [12].

7.2.3 Cytoreductive Surgery

As early as 1935 Meigs recognized the importance of cytoreduction and removing as much tumor as possible to improve the effects of postoperative radiation in the management of ovarian cancer [28]. Forty years later Griffiths published a study that demonstrated conclusively an inverse relationship between the maximal residual tumor diameter and patient survival [29].

Cytoreductive surgery or debulking is the standard treatment recommendation for patients with clinical stage II–IV disease [20–23]. Cytoreductive surgery can be performed at the time of index surgery termed primary cytoreduction, following neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or for recurrent disease termed secondary cytoreduction.

The aim of cytoreduction is to fully stage the disease and achieve maximal clearance to less than 1 cm residual disease, or resection of all visible disease in appropriate circumstances.

Procedures that may be considered for optimal surgical cytoreduction include radical pelvic dissection, omentectomy, bowel resection, diaphragm stripping, splenectomy, partial hepatectomy, and distal pancreatectomy [30].

Chi et al. studied the impact of extensive upper abdominal primary cytoreduction including splenectomy, distal pancreatectomy, hepatic resection, and resection of porta hepatis tumors (Group 2) compared to earlier more conservative cytoreduction which involved only TAH, BSO ± omentectomy, and bowel resection (Group 1). Optimal cytoreduction rates defined as <1 cm residual disease (total disease less than 1 cm left behind) increased from 50 to 70 % between groups 1 and 2.

Operative time and estimated blood loss were greater in group 2 than group 1, P < 0.001 for both; however, complication rates and length of hospitalization were not significantly different between the two groups [31].

For patients with bulky stage III/IV disease who are not surgical candidates, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by primary interval cytoreduction can be considered [16, 24, 26, 27, 32].

Secondary cytoreductive surgery can be considered for patients who experience recurrence after a long disease-free interval (>6 months) [33].

7.2.4 Liver Metastases from the Ovary

Ovarian malignancy can disseminate to the liver via intraperitoneal seeding or hematogenous spread.

With peritoneal seeding, initially the cells move downward into the pelvis due to the pull of gravity, and they then travel cranially in the circulating peritoneal fluid, moving through the right paracolic gutter to the pouch of Morrison and the right subdiaphragmatic space. The peritoneal fluid from the posterior subphrenic space travels along the right coronary ligament to the hepatic bare area and spreads throughout the perihepatic space.

The tumor cells initially seed to the liver capsule producing peritoneal lesion on the liver surface – stage III disease. The tumor can then advance to involve the liver parenchyma – stage IV disease [16, 18].

Hematogenous spread is generally seen in advanced disease the liver being affected in 48 % of cases.

Liver involvement can be present at the initial diagnosis of ovarian cancer usually due to peritoneal seeding, and the presence of adhesions resembling those seen in Fitz-Hugh-Curtis disease may be an early indicator of carcinomatosis [16].

Alternatively metachronous liver metastasis diagnosed during follow-up following initial cytoreduction and chemotherapy can occur. These can be either due to peritoneal seeding or hematogenous spread.

As stated liver involvement can therefore occur in both stage III and IV disease. Sixteen percent of ovarian cancer cases are stage IV at the time of diagnosis. Both stages of ovarian cancer have a poor prognosis with 5-year survival for stage III and IV disease approximately 37 and 25 %, respectively [34–36].

When considering liver resection in ovarian cancer metastasis, consideration needs to be given to the stage of disease and whether the tumor is synchronous or metachronous.

Liver resection has been considered in the setting of:

1.

Primary cytoreduction pre-chemotherapy treatment

2.

Primary cytoreduction following neoadjuvant chemotherapy

3.

Secondary cytoreduction for recurrent disease following primary cytoreduction and adjuvant chemotherapy

4.

Secondary cytoreduction for recurrent disease following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for bulky disease

7.2.5 Liver Resection for Ovarian Cancer

The literature surrounding liver resection for ovarian malignancy is limited and mainly restricted to retrospective reviews.

The majority of papers have reviewed the role of hepatic resection in secondary cytoreduction for recurrent disease following chemotherapy.

Liver resection has been carried out in the context of both stage III and IV disease, with and without the presence of extrahepatic disease. Resection was performed for both single and multiple metastases [37–43].

Median survival ranged from 11 to 62 months combining stage III and IV disease. Two studies looking at only stage IV had wide variation in median survival, 11 and 40 months [40]. Similar survival rates are seen with and without the presence of extrahepatic disease [38, 39, 41, 43].

There was no perioperative mortality reported, and complication rates are reported between 11 and 21 %. All studies had a long median disease-free interval ranged between primary cytoreduction and the development of liver metastasis ranging 32–68.5 months.

Both univariate and multivariate analysis demonstrated the importance of length of disease free interval to the development of liver metastases as a good prognostic factor. This possibly indicates favorable tumor biology. Other prognostic factors include optimal cytoreduction of residual disease to <1 cm and clear surgical margins, survival of 52 months with R0 resection compared to 22 months R1 [38]. Nui et al. found that the number of liver lesions affected prognosis [38], and this was however not found by others [37]. Abood et al. demonstrated improved prognosis if the size of the largest metastatic tumor was >5 cm, and speculating this may be due to overall less tumor burden due to smaller number of tumors [42].

Liver resection can be considered for both single and multiple liver lesions. The presence of extrahepatic disease should not exclude liver resection as long as adequate debulking is possible. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be performed in the presence of bulky stage IIIc/IV disease in an attempt to downstage the tumor and improve the chance of tumor clearance and achieving an R0 resection. In addition it may reduce the extent of resection required and therefore the possible surgical morbidity.

The patients considered for liver resection, as with other hepatic metastases, should have good performance status. Many of the patients undergoing secondary cytoreduction and liver resection subsequently completed a further course of adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2

Prognostic factors in liver resection as secondary cytoreduction for ovarian cancer

Disease-free interval from primary cytoreduction to liver metastases |

R0 resection |

Cytoreduction to <1 cm of residual disease |

Number of liver lesions |

Size of the largest liver lesion |

Liver Resection as a Component of Primary Cytoreduction

Less has been written about liver resection as part of primary cytoreduction. Lim and Bristow independently looked at the effect of hepatic resection as part of primary cytoreduction both before and after chemotherapy for synchronous liver metastases.

Bristow et al. retrospectively reviewed the results of primary cytoreduction for stage IV disease. In this population of patients, the median survival for those with synchronous parenchymal liver metastasis was 18 months. This was comparable to survival rates seen with pulmonary or other extrahepatic synchronous disease.

There was a significant relationship between performance status and survival following primary cytoreduction. In addition prognosis was significantly impacted on by the success of debulking. Those with <1 cm residual tumor experienced a 38.4-month median survival compared with 10.3 months for those with suboptimal debulking. The survival of those patients with parenchymal hepatic disease also correlated with the number of liver lesions, 1–2 hepatic lesions median survival 20.9 months compared with 6.4 months for patients with three or more lesions (P = 0.0012).

Lim et al. retrospectively reviewed hepatic resection as part of primary cytoreduction for hepatic parenchymal metastases from peritoneal seeding for both stage IIIc and IV disease and found 5-year progression-free survival rates of 25 and 23 %, respectively, and overall 5-year survival rate of 55 and 51 %, respectively [18].

In summary liver resection in the context of stage III/IV disease is a viable option with acceptable morbidity and mortality, which should be considered as part of cytoreduction in a selected patient population at the time of both primary and secondary cytoreduction.

7.3 Endometrial Cancer

7.3.1 Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most frequent malignant disease of the female reproductive tract [44, 45] accounting for 6 % of all cancers in women. The mean age at diagnosis is 68 years.

This malignancy, as a rule, has a good prognosis with postmenopausal bleeding allowing for early diagnosis. At the time of diagnosis, 75 % of patients have stage 1 disease with 5-year survival rates of up to 88.9 % [45, 46]. Stage IV disease is seen in only 3.7 % of patients at initial diagnosis but is responsible for 23 % of cancer-related deaths in the first year following diagnosis and has an overall 5-year survival rate of 10–25 % [46–49].

Most patients who die from their disease have metastases beyond the pelvis at the time of death. Studies suggest that death from endometrial cancer is largely due to abdominal and distant metastases with a high proportion demonstrating liver and lung involvement [45, 49]. Approximately 50 % of patients dying as a result of endometrial cancer will demonstrate hepatic metastases at autopsy [43].

In cases of endometrial cancer, the tumor markers CA 15-3, CA72-4, and CA125 have been correlated with the disease stage, depth of myometrial invasion, and nodal status [50, 51]. There is however no difference in tumor marker levels in patients with or without distant metastases. Endometrial cancer cells are also known to express CEA, and significant differences in the level of this marker have only been seen when both hepatic and pulmonary metastases are present [49].

As with ovarian cancer the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system is also used in the staging of endometrial cancer (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

FIGO staging of endometrial cancer

Stage I confined to the uterus |

Stage II involvement of the uterine cervix |

Stage III direct invasion to involve surface of the uterus, fallopian tubes, or vagina |

Stage IV distant metastases |

IVa to bowel, bladder |

IVb to the liver, lungs, bone |

Endometrial carcinoma has four histological subtypes (endometrioid, papillary serous, clear cell, carcinosarcoma) of which endometrioid subtype is the most common affecting 75–80 % of patients [45, 46, 52]. Unlike ovarian carcinoma it is an important independent variable for prognosis and potential treatment. Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma has a better prognosis than the other subtypes.

After surgical treatment of primary endometrial carcinoma, both local and distant recurrences are a serious concern in high-risk patients [53].

Recurrence is defined as “local tumor regrowth or the development of distant metastasis discovered 6 months or more after complete regression of the treated tumor.” Approximately 60 % of recurrences are seen within 2 years following primary treatment [54].

Local or pelvic recurrence in endometrial carcinoma is frequently seen in patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy alone and involves the vagina, pelvic nodes, cervix, adnexa, and peritoneum [55]. Adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy has been associated with decreased risk of local recurrence [56]. Peritoneal carcinomatosis is one of the most classical sites of recurrent endometrial carcinoma [57].

Endometrial cancer usually spreads by lymphatic dissemination. Hematogenous metastases are uncommon. The most common sites of distant metastases are the bone, lung, and liver [54]. Pulmonary metastases from gynecological malignancies are seen most commonly with endometrial carcinoma [54, 57]. Recurrent endometrial carcinoma is less commonly seen in intra-abdominal organs; however, the liver is the most common intra-abdominal organ to become involved. Liver metastases are seen as single or multiple liver lesions with peripheral enhancement [52].

PET/CT is a highly sensitive and specific modality in the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial carcinoma. It provides good anatomical and functional localization of sites of recurrence and distant metastases before it becomes symptomatic or detectable by other imaging modalities [52].

7.3.2 Liver Metastases from Endometrial Cancer

Published data on hepatic resection for metastatic endometrial carcinoma is sparse with all cases being of endometrioid histology [11].

In two case reports the patients underwent resection of isolated lesions followed by chemotherapy. One patient survived, and the second patient developed secondary recurrence at 8 months and died 2 months after this diagnosis [32, 43].

Chi had two patients with endometrial carcinoma in his series of gynecological malignancies and hepatic resection. Both were endometrioid, both had undergone TAH and BSO as primary treatment, both had single liver deposits, and both underwent postoperative pelvic irradiation. One patient had synchronous pulmonary metastases also resected.

One patient had synchronous pulmonary metastases also resected. One patient developed secondary recurrence in the brain which was resected with postoperative irradiation, and there was no evidence of disease 19 months after completing her radiotherapy [43].

Harrison published a series of 96 cases undergoing hepatic resection for non-colorectal non-neuroendocrine metastases including genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and soft tissue; this series included four endometrial carcinomas. There was no postoperative mortality, and there were some long-time survivors, but none of the endometrial metastases reached 5-year survival [2].

Knowles et al. retrospectively reviewed hepatic resection for endometrioid carcinoma of both ovarian and endometrial origin over a 20-year period. This made up only 0.8 % of the total liver resections performed in a tertiary referral hepatobiliary unit over this time period. Two were endometrial in origin with follow-up at 48 and 66 months showing both patients alive and disease-free [9] (Fig. 7.1).

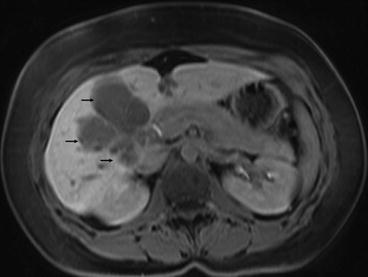

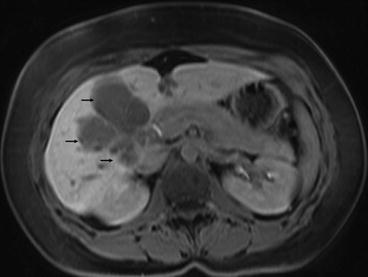

Fig. 7.1

MRI scan showing endometrial carcinoma metastasis in the right lobe of liver (black arrows). The lesion was resected by a right trisegmentectomy

Bristow et al. undertook a retrospective study of the role of primary cytoreductive surgery in the clinical management of patients with stage IVb endometrial carcinoma. An optimal surgical result was defined as no residual tumor nodule <1 cm in maximal diameter. Only one patient 1.5 % underwent liver resection as part of primary cytoreduction.

The median survival for the entire patient population was 14.8 months (range 0.4–102.7 months, mean survival 22.1 months). After a median follow-up of 14.7 months, 15 patients were alive without evidence of disease (23.1 %).

When evaluating adjuvant therapy modalities, no association between survival outcome and either chemotherapy or radiation therapy, when administered alone, was seen. In contrast, the 14 patients who received treatment with chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy had a median survival rate of 40.0 months, compared with only 14.0 months for patients not receiving this combination (P = 0.004).

Patients with a performance status of 0 demonstrated a statistically significant survival advantage (median survival 20.1 months) compared with patients with a performance status of ≥1 (median survival 10.5 months, P = 0.0005). Multivariate analysis only was presented which demonstrated that age <58 years (P = 0.023), performance status = 0 (P = 0.043), and residual disease <1 cm (P = 0.0001) maintained significance as predictors of survival. Residual disease showed the strongest independent effect. These findings are consistent with those seen with ovarian cancer (Table 7.4).

Table 7.4

Similarities and differences in presentation, prognosis and management of ovarian and endometrial cancer

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree