Tumors of Epithelial Origin | |

Neuroendocrine carcinoma Carcinoid tumor Bowen’s disease Perianal Paget’s disease Basal cell carcinoma Cloacogenic carcinoma Malignant melanoma Squamous cell carcinoma Adenosquamous carcinoma or adenoacanthoma Stem cell carcinoma | |

Tumors of Lymphoid Origin | |

Lymphoid hyperplasia, benign lymphoma, and lymphoid polyp Malignant lymphoma Extramedullary plasmacytoma | |

Mesenchymal Tumors | |

Fibrous tissue origin | |

Fibroma Inflammatory fibroid polyp or eosinophilic granuloma Fibrosarcoma Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | |

Stromal origin | |

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | |

Smooth muscle origin | |

Colonic leiomyoma Rectal leiomyoma Leiomyosarcoma Rhabdomyosarcoma | |

Adipose tissue origin | |

Lipoma Lipomatosis | |

Tumors of Neural Origin | |

Neurofibroma Ganglioneuromatosis Neurilemoma or schwannoma Granular cell tumor | |

Vascular Lesions | |

Hemangioma Lymphangioma Hemangiopericytoma Malignant vascular tumors (angiosarcoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma) | |

Heterotopias and Hamartomas | |

Endometriosis Perineal endometrioma Hamartoma Retrorectal (presacral) cysts (developmental cysts, including dermoid cyst, epidermoid cyst, tailgut cyst, enteric cyst, rectal duplication, neurenteric cyst, and teratoma) Colitis cystica profunda or enterogenous cysts Ectopic tissue | |

Exogenous, Extrinsic, and Miscellaneous Conditions | |

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma Choriocarcinoma Metastatic tumor Barium granuloma Oleoma, eleoma, oil granuloma, and paraffinoma Sarcoidosis Wegener’s granulomatosis Amyloidosis Amyloid tumor Malacoplakia Sacrococcygeal chordoma Ependymoma Extramedullary (extraadrenal myelolipoma or angiomyelolipoma) Anterior sacral meningocele Extramedullary hematopoiesis Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis or pneumatosis coli Duplication | |

Rochester, Minnesota, reported that more than one-half of the patients whose records were available survived 5 years.93 In the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience, metastatic disease was detected at the time of diagnosis in more than two-thirds of their patients.54

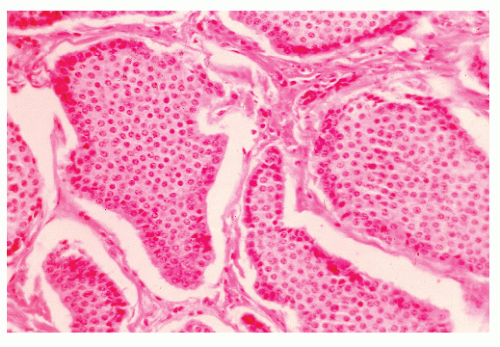

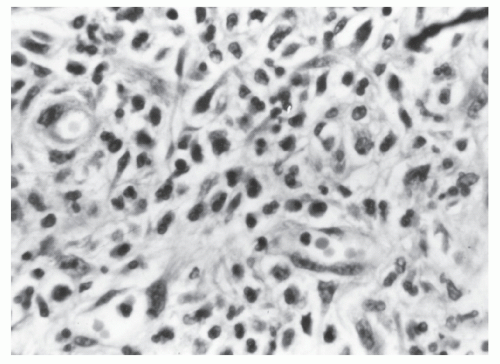

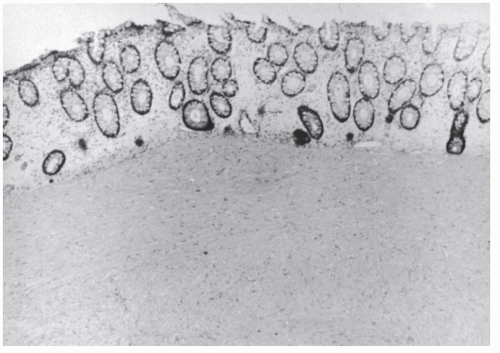

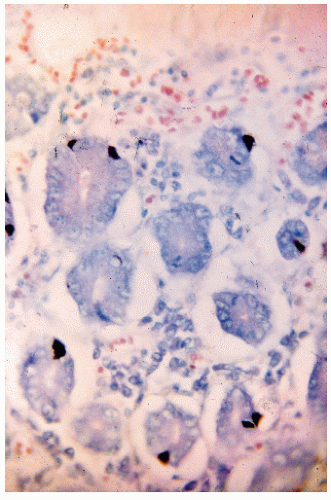

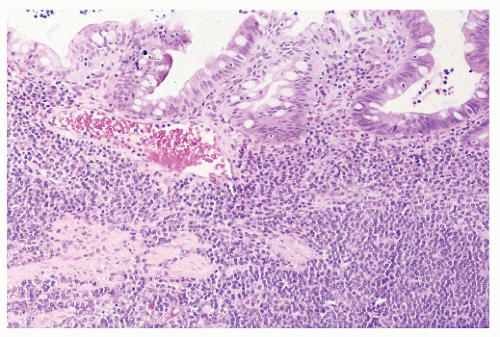

FIGURE 26-1. Normal bowel showing dark-staining argyrophilic granules (in Kulchitsky cells) from which carcinoid tumors arise. (Original magnification × 600; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

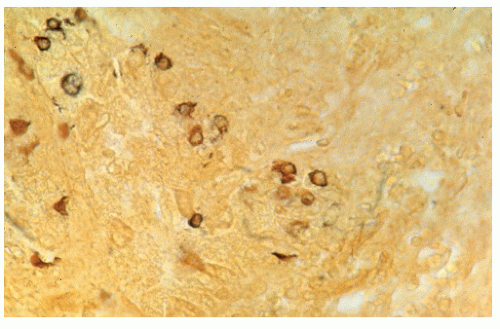

argyrophil or argentaffin positive, are usually unicentric, and are not associated with the carcinoid syndrome.383 Saegesser and Gross, however, reported the carcinoid syndrome in an individual with carcinoid of the rectum, and Taxy and associates noted, in 23 patients, that most rectal carcinoids are argyrophilic if the more sensitive Grimelius method is employed.433,499 In this same group of patients, only three were argentaffin positive. The authors concluded that the Grimelius argyrophil stain is the most accurate light-microscopic means for confirming the diagnosis of a rectal carcinoid.

|

FIGURE 26-2. Carcinoid tumor showing argyrophilic granules in the cytoplasm. (Fontana stain; original magnification × 600; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

TABLE 26-1 Classic Differences among Foregut, Midgut, and Hindgut Carcinoids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Small intestine (41.8%)

Gastric (20.5%)

Colonic (20.0%)

Appendiceal (18.2%)

GI carcinoid tumors is as high as 55%.206 This includes an increased risk for synchronous colorectal, small bowel, gastric and esophageal cancers, as well as metachronous lung, prostate, and urinary tract neoplasms.507 Because of the possible association with myelofibrosis, evaluation of the bowel in an individual with hematologic disease may be a useful exercise.368 An association between ulcerative colitis and rectal carcinoid tumors has also been postulated.445 The reason for the predisposition to develop other cancers may be due to the tumorigenic properties of the peptides secreted by NE cells, such as secretin, gastrin, bombesin, cholecystokinin, and vasoactive intestinal peptide.206

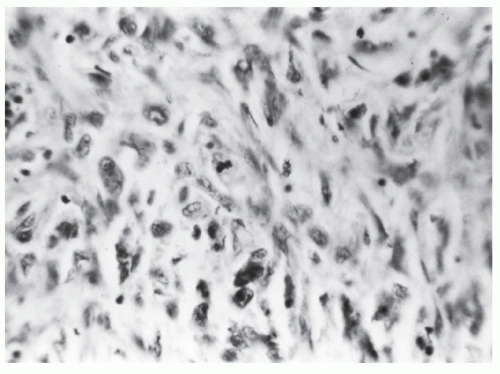

of an abdominal mass.323 Endoscopic ultrasonography has been found to be applicable for determining depth of invasion, a useful consideration if one were to consider performing a local excision.

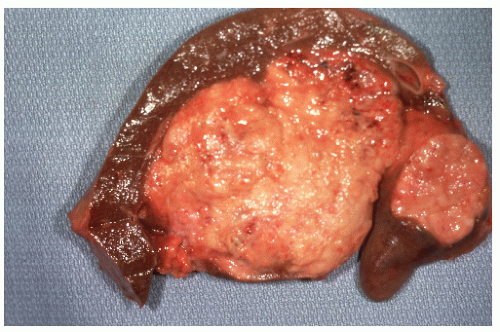

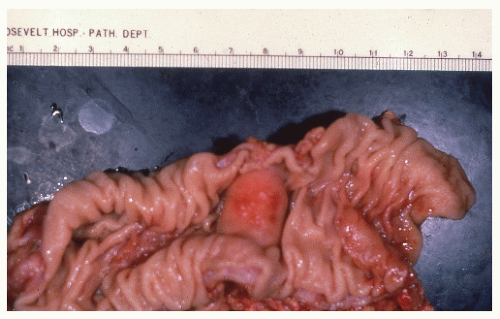

FIGURE 26-7. Longitudinal section of the specimen shown in Figure 26-6. Note the absence of infiltration of muscularis. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

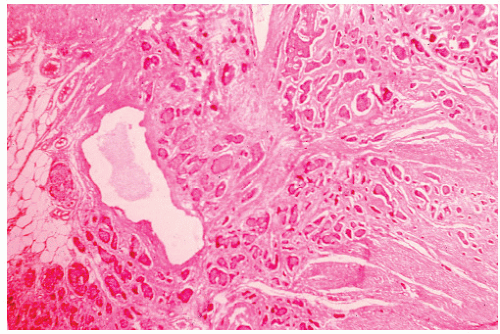

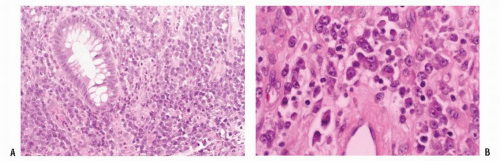

FIGURE 26-10. Malignant carcinoid. Uniform cells in tissue spaces, some forming abortive glandular structures. (Original magnification × 280; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

FIGURE 26-12. Carcinoid tumor of the appendix. Multiple cuts through resected specimen demonstrate macroscopic confinement of the tumor to the submucosa. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

protein metabolism in disorders such as carcinoid syndrome (Figure 26-16). The likelihood of developing the syndrome is dependent on the site of the cancer. Up to 60% of those with metastatic small bowel carcinoids will develop symptoms, whereas only about 1% of those with appendiceal primary disease will develop the syndrome. With the exception of the rare “case report,” virtually no one with a rectal carcinoid will ultimately develop the symptoms of carcinoid syndrome.

of the colon and rectum.538 When a distinction is made between cecal and other colonic sites, the former is found to be associated with a 71% incidence of metastasis, whereas the latter has a 33% incidence.441 Ballantyne and coworkers noted a 5-year survival rate of 37% in their 54 patients.38 Tumors larger than 2 cm had metastasized in approximately three-quarters of their patients, whereas only one in six less than 2 cm metastasized. Spread and colleagues noted that survival for carcinoids of the colon was significantly lower when compared with carcinoids of the rectum or appendix or with colonic adenocarcinomas.477 They, however, believed that size and tumor invasion were not the major prognostic factors. Rather, tumor stage, histologic pattern, tumor differentiation, nuclear grade, and mitotic rate were found to influence the survival rate significantly.477

Metastases from another site must be excluded.

A squamous-lined fistula tract must not involve the affected bowel.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus with proximal extension must be excluded.

squamous cell carcinoma.413 A case report of squamous cell carcinoma of the sigmoid colon with metastatic disease to the liver has been reported that responded well to systemic chemotherapy.258

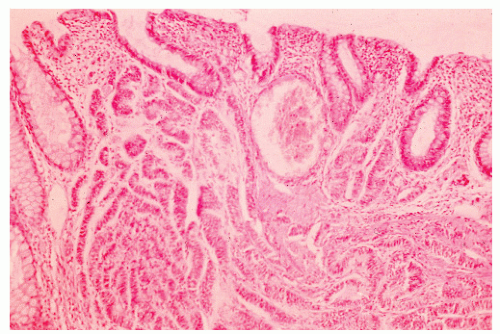

that lesions of the GI tract may be limited or diffuse and sometimes are associated with widespread lymphoid hyperplasia but never with leukemia. Symmers confirmed these findings in 1948.495 Since that time, isolated cases have been reported sporadically, all of which confirm the benign nature of the disease.70,98,108,242,256

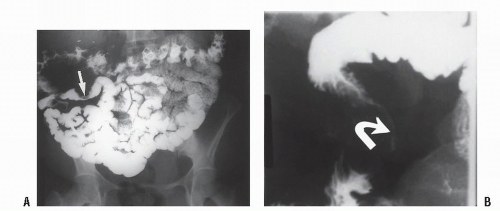

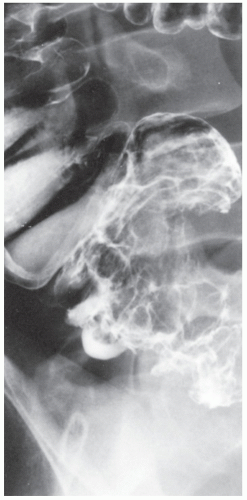

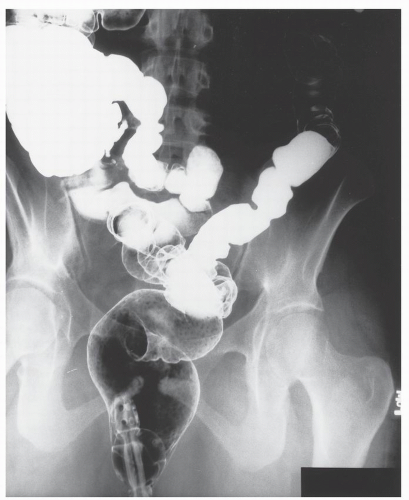

FIGURE 26-19. Lymphoid hyperplasia. Numerous small filling defects are evident in the rectum on this air-contrast barium enema study. |

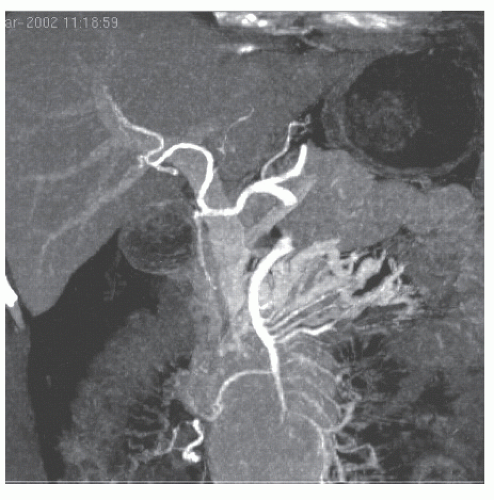

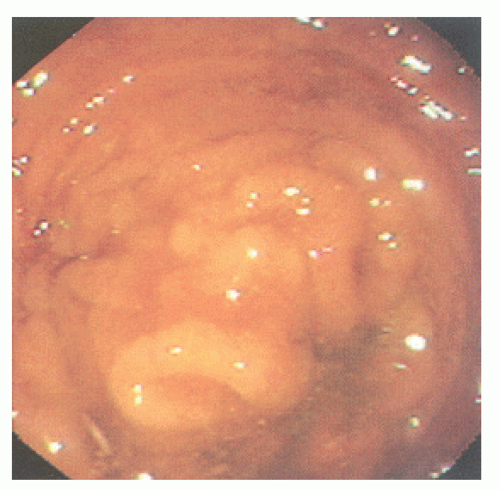

FIGURE 26-20. Colonoscopy reveals numerous confluent, sessile, mucosal nodules. Biopsy was consistent with nodular lymphoid hyperplasia. |

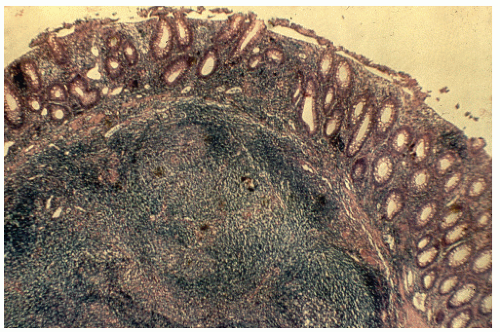

FIGURE 26-21. Lymphoid polyp of the rectum. Lymphocytic infiltration with irregular germinal centers in the submucosa. (Original magnification × 250; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

FIGURE 26-22. Autopsy specimen showing leukemic infiltration of the bowel wall simulating scirrhous carcinoma. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

concomitant leukemia, total and differential white blood cell counts are mandated as part of an evaluation.544

Abdominal pain (65%)

Abdominal mass (54%)

Weight loss (43%)

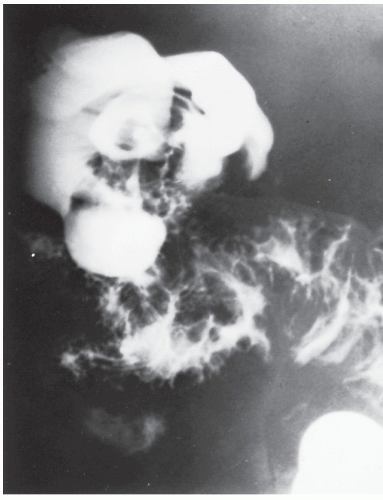

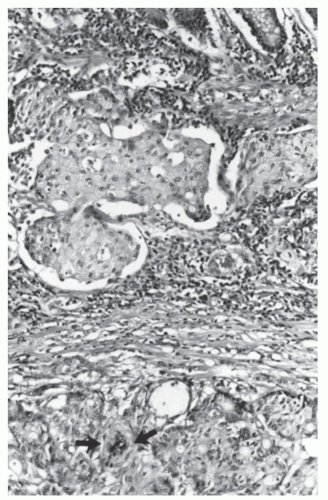

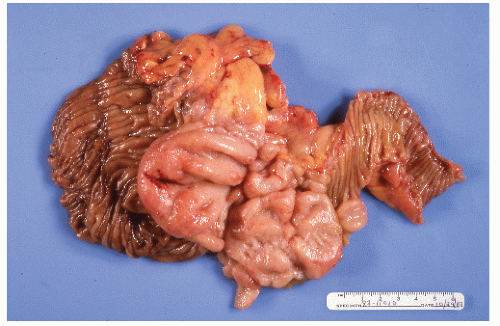

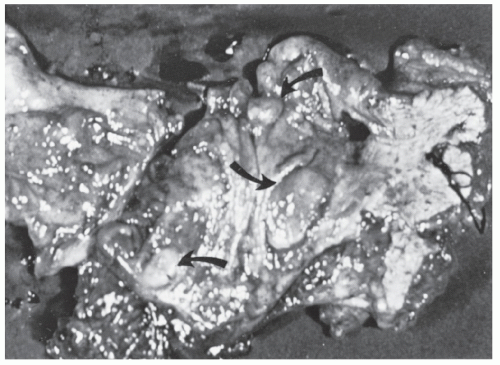

FIGURE 26-23. Lymphomatous infiltration of the rectum treated by abdominoperineal resection. Multiple lesions (arrows) are noted. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

the following histologic types: lymphocytic lymphoma, lymphosarcoma, reticulum cell sarcoma, giant follicular lymphoma, and Hodgkin’s disease. Hodgkin’s disease of the colon or rectum is the rarest.

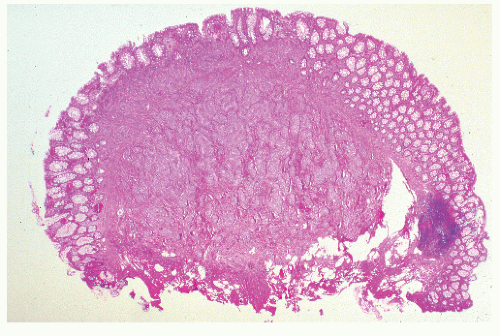

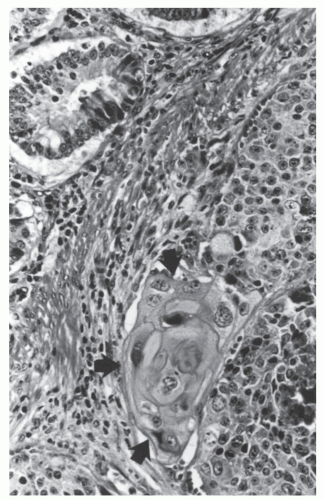

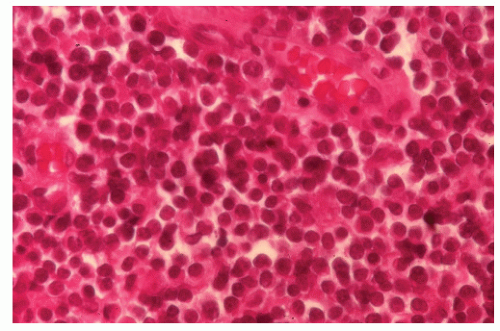

FIGURE 26-27. Lymphoma of the sigmoid colon. Note the heavy infiltrate of lymphocytic tumor cells involving the mucosa and submucosa. (Original magnification × 80; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

obstruction), and fatigue (from anemia). About one-half have metastatic disease at the time of presentation.159

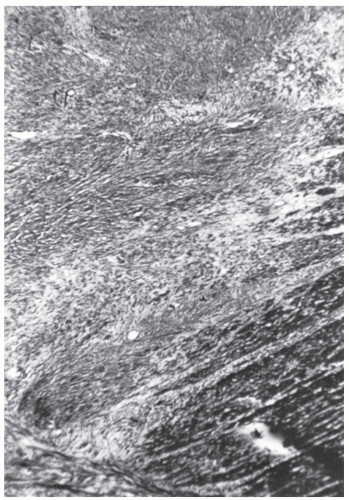

FIGURE 26-31. Fibrosarcoma. A well-differentiated tumor infiltrating the wall of the bowel. (Trichrome stain; original magnification × 80; courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

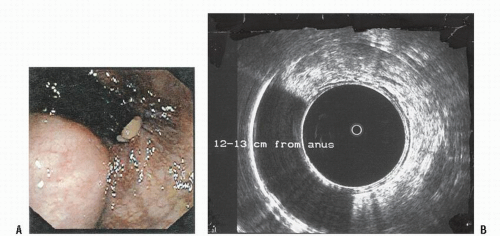

mutation in platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA).186

|

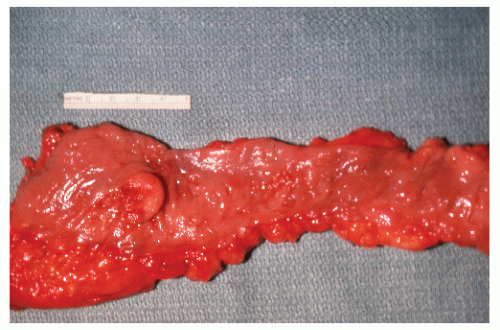

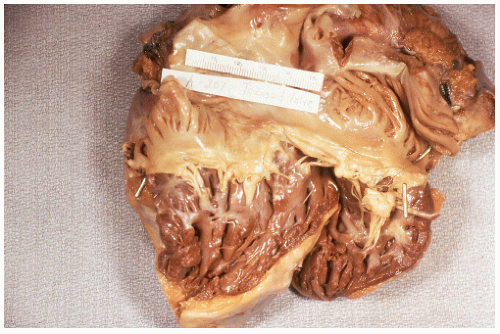

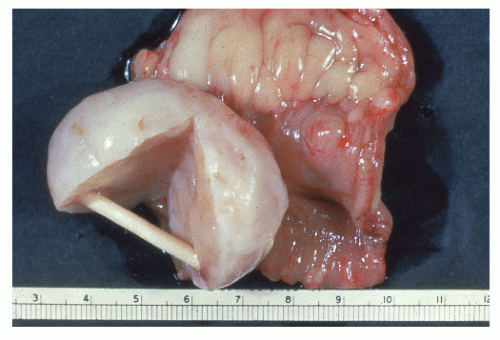

because the tumor is under pressure, it tends to protrude (Figures 26-35,26-36,26-37 and 26-38).

experience at the Research Institute of Proctology in Moscow.525 Thirty-six patients with benign leiomyoma of the rectum underwent surgery between the years 1972 and 1990. Approximately one-third were male. In this experience, the tumors often tended to arise from the internal anal sphincter. Some investigators have found that endorectal ultrasound is helpful in determining the limits of the lesion.451 A homogeneous hypoechoic tumor without invasion of the perirectal tissue may be noted.236

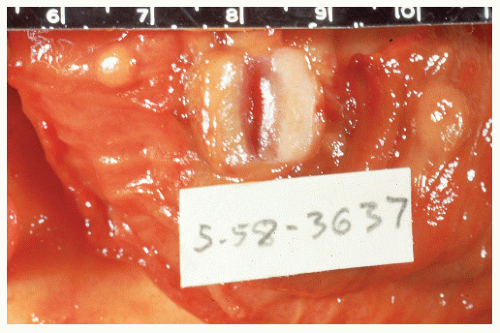

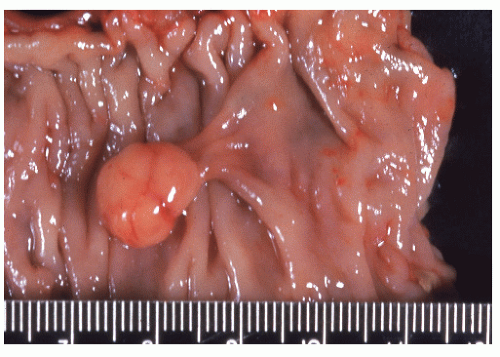

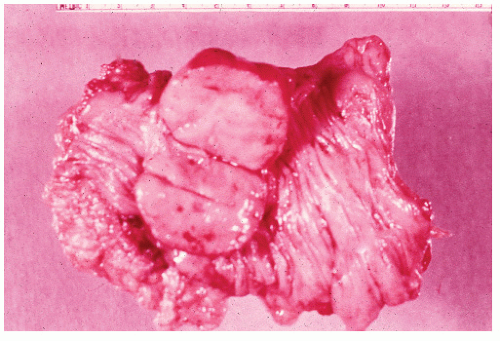

FIGURE 26-36. Leiomyoma. A well-encapsulated mass in the bowel wall. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

tumors (see earlier discussion).21,30,35,73,90,119,234,412,449,480 No age predilection for this disease is apparent. It affects the genders equally and is more than twice as common in the rectum as it is in the rest of the colon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree