Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) is a technically challenging procedure with up to 5-year follow-up data. In this article, incidence of renal cell carcinoma, indications, and contraindications for LPN are presented. In addition, LPN for benign diseases such as atrophic renal segments associated with duplicated collecting systems and calyceal diverticula associated with recurrent UTIs are presented. Hilar clamping, ischemic time, positive margins, and port-site metastasis, in addition to complications and survival outcomes, are discussed. The advantages of lower cost, decreased postoperative pain, and early recovery have to be balanced with prolonged warm ischemia. Its long-term outcomes in terms of renal insufficiency or hemodialysis requirements have not been defined completely. Randomized clinical trials comparing open partial nephrectomy (OPN) versus LPN are needed.

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common malignancy of the kidney and accounts for approximately 3% of adult cancers . It comprises 85% of newly diagnosed malignancies of the kidney, with an age-adjusted incidence of 12.8 cases per 100,000 population and age-adjusted mortality rate of 4.2 deaths per 100,000 population . Incidence rates have been increasing over the last 30 years in the United States, particularly among African Americans . During 2007, it was estimated that approximately 51,190 new cases of kidney cancer would be diagnosed, and 12,890 people would die of the disease in the United States . Factors such as increased resolution and application of imaging modalities have led to an increase in the incidental detection of renal masses. Classically, radical nephrectomy has been described as the standard surgical therapy for renal masses. Several studies, however, have indicated that partial nephrectomy provides cancer control similar to radical nephrectomy . Furthermore, partial nephrectomy has been shown to decrease risk of end-stage renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy when compared with radical nephrectomy . Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN), introduced in 1993, has become an acceptable alternative to open partial nephrectomy for expert laparoscopic urologists . Initially, LPN was used for benign disease such as lower-pole calyceal diverticulum containing a calculus, or atrophic hydronephrotic moiety . Laparoscopic hemi-nephrectomy also has been successful for nonfunctioning renal moieties in the pediatric population . This article presents some of the earliest series and the latest largest series ( Table 1 ).

| Senior author | Years | # | Age | Size (cm) | Trans/retro | Operating room (minutes) | Ischemia (minutes) | EBL (mL) | Histology | Stage | LOS (days) | Follow-up (months) | Local Rec | Mets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayman a | 93–98 | 3 | 68 | 1.2 (1–1.5) | 1 Trans; 2 retro | 210 (120–324) | 0 | 92 (75–100) | 2 (66%) Benign;1 (33%) RCC |

|

|

|

|

|

| Abbou | 95–98 | 13 | 42.9 | 3.2 (2–6) | Retro | 113 (60–200) | 7.4 (2–10) | 72 (0–400) | 8 (61%) Benign;5 (39%) RCC | 3 pT1a | 6.1 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Janetschek | 94–99 | 25 | 62.9 | 1.9 (1–5) | 15 Trans; 10 retro | 163.5 (90–300) | N/A | 287 (20–800) | 6 (24%) Benign;19 (76%)RCC |

| N/A | 22.2 (1–65) | 0 | 0 |

| Janetschek | 04–05 | 25 | 60.4 (40–74) | 2.6 (1.1–3.9) | Trans | 211.7 (155–260) | 28.9 (19–40) | 177.4 (50–1500) | 6 (24%) Benign;19 (76%) RCC; 0% +M |

| 8.3 (5–13) | 6.2 (1–15) | N/A | N/A |

| Gill | 99–01 | 58 | 64 (30–85) | 2.9 (1.3–7) | Trans and retro | 180 (45–348) | 23 (9.8–40) | 270.4 (40–1500) |

|

| 2.2 (1–9) | 68.4 (60–82.8) | 1/37 (2.7%) | 0 |

| Gill | 01–04 | 100 | 64 | 3.2 ±1.5 | Trans | 208±52 | 31.1 ± 9.2 | 221 ± 226 | 75%RCC;2% +M | N/A | 2.9 ±1.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Gill | 01–04 | 63 | 60 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | Retro | 173±54 | 28.0±9.0 | 217 ±285 |

| N/A | 2.2 ±1.6 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kavoussi | 99–04 | 217 | 56.6 | 2.6 (1–10) | 199 Trans; 18 retro | 186 (75–400) | 27.6 (5–60) | 385 ±377 | 66% RCC;3.5% +M | N/A | 3.1±1.6 | 24±12 | 2 (1.4%) | 0 |

| Ramon (2nd group) | 02–06 | 110 | 62 | 3.9 (1.4–6.2) | Trans | 100 (75–140) | 30 (18–49) | 510 (20–1200) | 15 (14%) Benign;95 (86%) RCC; 3.6% +M | N/A | N/A | 16 (4–42) | 0 | 0 |

| Average (range) | 93–06 | 614 | 60 (30–85) | 3.1 (1–10) | 449 Trans; 91 retro | 171 (45–400) | 27.8 (2–60) | 332 (0–1500) | 178 (29%) Benign;436 (71%) RCC; 3.2% +M |

| 3.2 (1–13) | 26.8 (1–83) | 1.7% (1.4–2.7) | 0 |

a Patients with exophytic renal masses who underwent wedge resection were included in the table.

Indications and contraindications

Initially, absolute indications for partial nephrectomy included localized enhancing renal masses in solitary kidneys, bilateral synchronous renal masses, or chronic renal insufficiency . Relative indications for partial nephrectomy are hereditary forms of renal cell carcinoma such as von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL), hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma, Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, or tuberous sclerosis, where there is increased risk of metachronous renal malignancies. These tumors often present at a younger age and are more likely to be multifocal and bilateral . Relative indications for partial nephrectomy also exist when the contralateral kidney is at increased risk of failure because of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nephrolithiasis, or chronic pyelonephritis . Finally, elective indications include localized incidental renal-enhancing masses with a normal contralateral kidney. These indications originally were described for open partial nephrectomy, but they are also applicable to LPN. Contraindications to partial nephrectomy include renal vein or inferior vena cava tumor thrombus, massive tumor size, and local invasion. Relative contraindications include lymphadenopathy and bleeding diathesis . Although initially partial nephrectomy was limited to 4 cm masses because of lower risk of local recurrence and multifocality, recently size criterion has been abolished as long as the tumor can be resected effectively with a negative margin . This has been shown for open partial nephrectomy (OPN) versus radical nephrectomy, and it also may be applicable for LPN versus laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. This remains a controversial issue.

When there is a normal contralateral kidney, increased risks of peri-operative complications of partial nephrectomy, local recurrence, and tumor multifocality have to be balanced with decreased risk of developing chronic renal insufficiency . In a review of 878 patients who had OPN, the rate of operative mortality was 1%, urine leak 7%, abscess 1%, bleeding 2%, and reoperation 2% . In addition, the overall risk of local recurrence in partial nephrectomy series has been found to be 0% to 10% depending on tumor size, histology, and stage. For tumors 4 cm or less, the local recurrence risk is even lower, at 0% to 3% . Furthermore, histologic pattern, such as papillary, rather than tumor size, has proven to be the most reliable predictor of multicentricity .

As with any new laparoscopic procedure, patient selection is crucial for success. Initially, LPN focused on those patients who had unifocal, small, polar, exophytic lesions, with a limited depth of penetration of less than 1 cm through the renal cortex. With evolution of the technique and improved methods of hemostasis, hilar and endophytic lesions, and masses abutting the collecting system can be resected .

Comparison with open partial nephrectomy

There are several retrospective series demonstrating advantages of LPN over the traditional OPN. These include lower narcotic requirements, improved cosmesis, earlier resumption of diet, shorter hospitalization, and lower expense . Furthermore, in a larger series from the Cleveland Clinic, LPN, as compared with OPN, was associated with a shorter surgical time, lower blood loss, longer warm ischemia (27.8 minutes versus 17.5 minutes), and higher rate of intraoperative complications (5% versus 0%) . In a multicenter comparison of 771 LPNs versus 1028 OPNs, LPN was associated with longer ischemia time and more postoperative complications (especially urological), in addition to its benefits of shorter operative time, decreased blood loss, and shorter hospital stay . Selection bias of more complicated patients for OPN is evident from these retrospective studies. The advantages of lower blood loss, shorter hospitalization, and convalescence, however, are evident. To provide level 1 evidence, randomized trials comparing the two procedures are needed.

Comparison with open partial nephrectomy

There are several retrospective series demonstrating advantages of LPN over the traditional OPN. These include lower narcotic requirements, improved cosmesis, earlier resumption of diet, shorter hospitalization, and lower expense . Furthermore, in a larger series from the Cleveland Clinic, LPN, as compared with OPN, was associated with a shorter surgical time, lower blood loss, longer warm ischemia (27.8 minutes versus 17.5 minutes), and higher rate of intraoperative complications (5% versus 0%) . In a multicenter comparison of 771 LPNs versus 1028 OPNs, LPN was associated with longer ischemia time and more postoperative complications (especially urological), in addition to its benefits of shorter operative time, decreased blood loss, and shorter hospital stay . Selection bias of more complicated patients for OPN is evident from these retrospective studies. The advantages of lower blood loss, shorter hospitalization, and convalescence, however, are evident. To provide level 1 evidence, randomized trials comparing the two procedures are needed.

Technique

The technique of LPN, both transperitoneal and retroperitoneal, has been detailed in schematic form in a recently published atlas . The authors would like to emphasize certain points. Knowledge of the tumor in relationship to the collecting system, renal hilum, as well as proximity to the vascular structures, will help guide dissection, isolation, and resection of the mass. Three-dimensional reconstruction following helical CT scan or magnetic resonance angiography allow high-quality images of the renal artery and vein and provide multiple views of the intrarenal anatomy . Preoperative knowledge of the number and location of renal arteries and veins improves intraoperative planning and surgical dissection.

No hilar clamping

The earliest LPN series was performed on small (less than 2 cm) exophytic lesions without hilar dissection or clamping. Janetschek and colleagues reported on 25 patients who underwent wedge resection of small (less than 2 cm) exophytic lesions with an average blood loss of 287 mL (range of 20 to 800 mL). In this technique, bipolar coagulation forceps were used for simultaneous dissection and hemostasis. In this series, there was 8% rate of urinary fistula postoperatively. This technique of resection without hilar clamping may be applicable for small exophytic lesions with depth of invasion less than 1 cm from the surface . For larger and central lesions, however, hilar control is essential. A novel technique of clamping the renal parenchyma with a Satinsky clamp (Aesculap Inc., Center Valley, Pennsylvania) inserted through a separate 1 cm stab incision has been described . Preliminary results in five patients with polar lesions averaging 3 cm showed the mean blood loss was 250 mL, and none required transfusions. This technique, however, is not applicable to renal masses involving the hilum or deeper invasion into the collecting system.

Habib radiofrequency technique

Another way of minimizing warm ischemia time without clamping the renal hilum is the use of a laparoscopic Habib probe (AngioDynamics, Queensbury, New York). It is a four-pronged bipolar radiofrequency device that ablates tissue between the probes in a bipolar fashion. Using the Habib probe, an avascular plane is created 10 mm away from the renal lesion. Its use has been shown to reduce transfusions in liver resections . The Habib probe was evaluated in a pilot study of three patients undergoing LPN without hilar clamping. The mean estimated blood loss was 100 mL, and none of the patients required transfusions . Cautery artifact, however, can cause difficulty in interpreting the frozen section margin. Randomized studies are needed to further evaluate its impact on blood loss, frozen section analysis, and long-term renal function.

Methods of hilar clamping and warm ischemia

To replicate OPN and perform LPN on larger (greater than 2 cm), endophytic, central, or hilar lesions, it is essential to control the renal hilum (either the renal artery alone or together with the renal vein). The advantage of hilar control is the ability to tackle lesions that once were thought to be only amenable to OPN. This has two primary functions: decreasing intraoperative hemorrhage and improving access to the renal collecting system for repair . There are three techniques of hilar control.

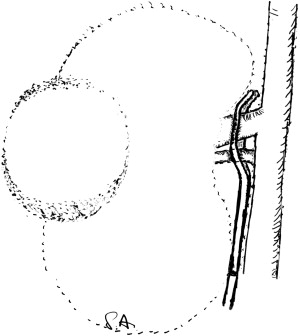

Gill was the first to demonstrate that LPN can duplicate open surgical principles . Laparoscopic bulldog clamps are the most widely used instruments to clamp the renal artery alone, or together with the renal vein (Aesculap Incorporated, Center Valley, Pennsylvania) ( Fig. 1 A, B). The advantages include ability to individually clamp the artery, and the ease of applying and removing. It also frees up a port for the most crucial part of the surgery: reconstruction of the nephrotomy defect. It is the personal preference of the authors to use the same instrument to place and remove the bulldog clamp. Disadvantages include difficulty in removing the clamp if not aligned well with the applicator.

Another option of clamping the renal vessels laparoscopically is the use of laparoscopic Satinsky clamps, which allow en bloc clamping of the entire renal hilum ( Fig. 2 ). The advantage is that the renal artery and vein can be taken en bloc and do not have to be dissected individually. The disadvantage is that an additional port must be employed to place the instrument. In addition, the assistant must take care not to exert excessive traction or pressure on the clamp inadvertently to avoid stretch or intimal injury to the vessel.

Finally, a Rumel tourniquet can be used to efficiently achieve vessel control and occlusion. The renal vein and artery are secured en bloc by an umbilical tape (Bard PTFE, Braided tape, 4 mm × 61 cm) (Bard Inc., Murray Hill, New Jersey), inserted through a 10 mm trocar. The tape is left in place until the end of the procedure and can achieve rapid reocclusion of the vessels if needed. To free the trocar from the umbilical tape, the trocar is removed and repositioned with the tape on the outside of the trocar. The Rumel tourniquet consists of a 5 cm piece of silicone drainage tube (10F) and a 20 cm vascular loop folded over once to form a U loop ( Fig. 3 ).

Besides being able to perform LPN on more complex renal lesions, the advantages of hilar control also include lower rates of urinary fistula (1.4% to 4%) ( Table 2 ). The most significant disadvantage of hilar control, however, is ischemia. Prolonged periods of ischemia result in acute tubular necrosis and renal failure. Intravenous mannitol 12.5 g is often administered before clamping. This has several protective mechanisms, such as: free radical scavenger, decreased intracellular edema, decreased intrarenal vascular resistance, increased blood flow and glomerular filtration rate of superficial nephrons, and osmotic diuresis . Furthermore, furosemide is administered to promote diuresis after unclamping of the renal vessels.

| Senior author | Years | # | Trans/retro | Overall complications | Open conversion | Bowel injury | Urinary fistula (%) | Hemorrhage (%) | Number reoperation (%) | ARF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayman | 93–98 | 3 | 1 Trans; 2 retro | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abbou | 95–98 | 13 | Retro | N/A | 0 | 0 | 2 (15%) | 0 | 1 (8%) Completion nephrectomy | 0 |

| Gill | 99–01 | 200 | Trans and retro | 66 (33%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 9 (4.5%) | 19 (9.5%) | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) |

| Gill | 01–04 | 100 | Trans | 18 (18%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (2%) | N/A | 3 (3%) |

| Gill | 01–04 | 63 | Retro | 6 (10%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | N/A | 0 |

| Gill | 03–05 | 200 | 146 Trans; 54 retro | 38 (19%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 | 4 (2%) | 9 (4.5%) | 3 (1.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Kavoussi | 99–04 | 217 | 199 Trans; 18 retro | 23 (10.6%) | 4 (1.6%) | 0 | 3 (1.4%) | 4 (1.9%) | N/A | 2 (0.9%) |

| Average | 93–05 | 796 | Laparoscopic | 151 (19%) | 10 (1.3%) | 2 (0.3%) | 24 (3%) | 36 (4.5%) | 8 (1.9%) | 10 (1.3%) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree