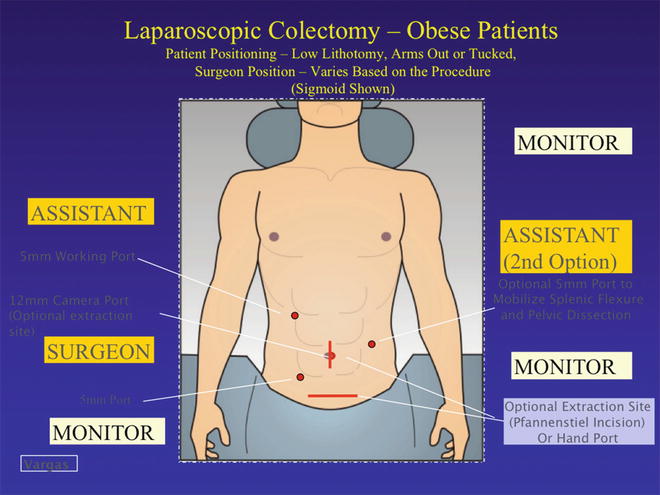

Fig. 29.1

Pigazzi patient positioning system™. Notice the steep positioning that is required

Defining an Operative Plan and Precise Preoperative Localization of Pathology

A fundamental aspect of the preoperative phase of surgery involves developing the operative plan (Table 29.1). For an elective colectomy, this should include the preoperative diagnosis, the anticipated extent of resection, incision/port placement, exposure strategy, dissection and mobilization, vascular ligation, bowel resection, and anastomosis. Execution of the plan remains dependent upon the actual circumstances encountered at the time of operation. Surgeons must consider prior to surgery all of the potential variations that may be encountered and how such endeavors enable one to adapt and press on when the unexpected occurs. While it is impossible to anticipate every possible variation, reducing such variables improves operative efficiency.

Table 29.1

Preoperative considerations

• Surgeon well experienced with laparoscopy |

• Patient selection |

• Preoperative expectations |

– Increased likelihood for need for conversion |

– Longer operative time |

• Bowel prep |

– May need longer bowel preparation |

– When optimized, can improve exposure with decompressed bowel |

• Antibiotic prophylaxis |

– Appropriate weight-based dosing for preoperative administration |

• Perioperative DVT prophylaxis |

One aspect of preoperative planning which requires additional consideration is the localization of the pathology to be resected and specifically when dealing with small tumors or polyps. In the case of inflammatory conditions, imaging will generally identify the segment of bowel to be resected. For polyps or tumors, we use preoperative colonoscopy. The colonoscopic description of location identifies the segment, while tattooing techniques enable intraoperative confirmation. Clearly, the experienced surgeon should maintain a healthy skepticism of the precision of colonoscopic descriptions, as inaccuracies persist irrespective of the experience and skill of the endoscopist. The tattoo is often viewed as the “fail-safe” alternative at operation. However, in the obese patient, failure to easily identify the lesion (even with preoperative marking) can become exasperating, and dissection may become paralyzed by the lack of confirmation of the target lesion. A large omentum, enlarged appendices epiploicae, and abundant retroperitoneal and mesenteric fat can all lead to the tattoo mark not being seen. This can be especially problematic when attempting to use a medial-to-lateral mobilization technique, which often involves initial proximal vessel ligation. One would be hesitant to perform this “point of no return” maneuver without first identifying the tattoo. Tattoos in the region between the hepatic flexure and the sigmoid colon are particularly at risk for such difficulties given the size and weight of the omentum in the obese patient. Intraoperative colonoscopy certainly is often available in most operating rooms, but this can be time-consuming, has potential drawbacks related to sterility, and any bowel distension in the obese patient will be disastrous. As such, the surgical team can expend considerable energy and time that otherwise could be invested later in the case where it is truly needed. If intraoperative colonoscopy is used to help localize the tattoo marking, we recommend CO2 instead of air insufflation, as this will dissipate from the bowel and cause less bowel distention.

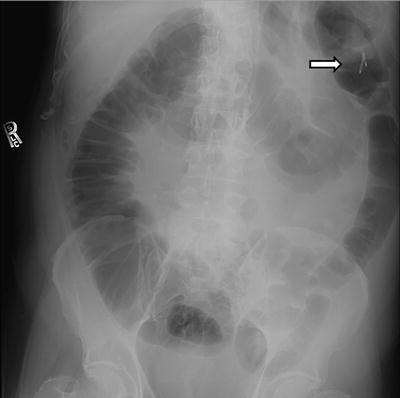

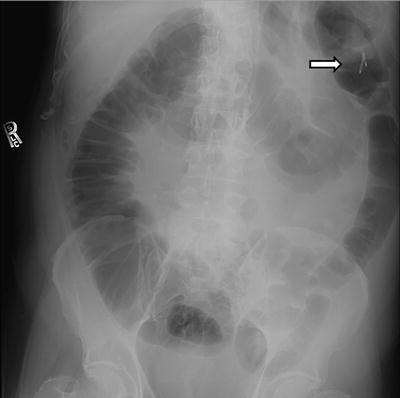

Techniques for localization prior to operation include both imaging and endoscopic means. As said, larger lesions can be seen on barium enema or on CT scan. The operating surgeon can also repeat the colonoscopy to confirm the lesion location, with two methods classically utilized for marking. First, an abdominal radiograph is taken with the tip of the scope at the lesion (Fig. 29.2). Second, an endoscopic clip can be placed at the lesion and abdominal films performed immediately after colonoscopy (Fig. 29.3).

Fig. 29.2

Localization of small tumor using radiograph with colonoscopy

Fig. 29.3

Localization of tumor by endoclip placement (arrow) and post-procedure radiograph

Preoperative marking with abdominal radiographs also allows you to identify (prior to surgery) lesions that do not readily fit into standard segmental resections (i.e., right or sigmoid colectomy). This would include lesions between the hepatic flexure and the descending colon. In a challenging patient such as obese patients, this prepares the surgeon and the patient ahead of time and enhances the execution of the plan. Surgeons can also more accurately counsel patients both for what to expect in the operating room and potential changes in postoperative function. For example, if both are under the impression that a lesion is in the “sigmoid colon” and then to find it in the proximal descending colon or splenic flexure, this will demand an entirely new plan for resection which is technically much more difficult in the obese patient. In essence, the goal remains to pursue any means possible to reduce the likelihood of a preventable “surprise” at the time of operation that will impact the execution of the operative plan.

Alterations of Anatomy and the Technical Challenge of the Obese Patient

The fundamental difference in obese patients is the loss of abdominal domain with laparoscopy and increased abdominal wall thickness. In male pattern obesity or central obesity, the former can be expected to be more of a problem. This is the result of the abundant retroperitoneal fat as well as intraperitoneal adipose tissue that diminishes the volume of space created by pneumoperitoneum and reduces overall laparoscopic perspective and visualization. The larger and heavier bowel along with its associated bulky mesentery proves much more difficult to manipulate and retract with the miniature end effectors of laparoscopic instrumentation. In addition, retraction of the small bowel proves much more problematic, with limited “room” in the abdomen and requires systematic and disciplined techniques, as simple positional changes and the effect of gravity are less effective. Mesenteric thickness makes dissection and control of vascular structures much more tedious and stressful, as major vessels are not only not readily identified but also more difficult to control if bleeding occurs. Mesenteric obesity also shortens effective bowel length and impacts various anastomotic techniques. Essentially, every aspect of surgery is made more challenging in the obese patient, and you must prepare specifically for such an endeavor.

One such way to overcome this is to increase the pneumoperitoneum and create a more “doming effect.” Some have suggested using two insufflators to accomplish this. However, cardiopulmonary compromise, as indicated by hypercarbia or hypotension, can result due to decreased venous return. This must be anticipated and monitored closely by the surgical and anesthesia team with appropriate cardiovascular monitoring as indicated, taking into account underlying cardiopulmonary conditions, effect of bowel preparation, expected blood loss, and duration of surgery.

Ergonomic Issues in Laparoscopic Colectomy in the Obese Patient

The man-machine environment of the laparoscopic operative suite presents certain ergonomic challenges for the operating surgeon and team. Design of instruments, monitor height and location, table height, and surgeon positioning and posture all affect the surgeon’s experience and as a consequence, the technical conduct of the operation. During laparoscopic operations, surgeons suffer from high levels of mental and physical stress. After a certain time—~4 h—the so-called surgical fatigue syndrome may occur. This syndrome includes mental fatigue, degradation of manual dexterity, and importantly a reduced capacity for good judgment results [26]. This can be further exacerbated when operating on the obese patient.

To help overcome this, you must consider specific ramifications of the girth of the patient: alterations in the vertical height of the operating field (i.e., ventral surface of the patient), the increased lateral distance to the operative field, and the consequences for surgeon position and posture. Surgeons must consider step stools to return hand and wrist height to the more comfortable posture with optimal height at level of elbows [27]. As the ports will be further away from the surgeon’s center of gravity, flexion and adduction of the shoulder occurs. This again reduces ergonomic efficiencies and exacts a physical toll. Seemingly trivial, these physical challenges will be magnified over the course of a longer operation. Fatigue and mental stress contributes to frustration and intolerance of additional procedural difficulties that are naturally expected to occur in a complex operation as laparoscopic colectomy. With obese patients, it is simply exacerbated. Therefore, as you prepare for this patient group, identifying means to reduce physical stress and improving ergonomics of surgical technique will enhance your comfort and physical experience, and as a consequence, improve patient surgical outcomes.

Learning Curve for Laparoscopic Colectomy in the Obese Patient

Another concept to consider is a learning curve that is specific to complex operations—in this case the obese patient. In general, the learning curve for laparoscopic colectomy has been well described as being longer than that for other laparoscopic procedures, varying first by specific procedure (right vs. left vs. total colectomy) [28]. In regard to patient-related factors, obesity presents a greater technical challenge and results in a longer learning curve to achieve proficiency. Sarli et al. demonstrated that when operating on obese patients. Risk of conversion decreased with increased surgical team experience [29]. Yet the learning curve must also account for various pathologic conditions such as those related to inflammation (i.e., diverticulitis or Crohn’s disease) as well as locally advanced cancer. Therefore, especially early in your practice experience and learning curve, it is imperative that you consider all factors which make an operation complex: (1) patient-related factors such as obesity or severe comorbid conditions; (2) disease-related factors such as severe inflammation complicated by phlegmonous masses or fistulas; (3) large neoplasms demonstrating local invasion; (4) complex resections such as left colectomy, extended resections, and total abdominal or proctocoloectomy; or (5) acute emergent presentation of disease such as perforation, hemorrhage, or large bowel obstructions. Such factors should each be considered into the decision to attempt laparoscopic colectomy.

Given that over 1/3 of our patient population now presents with BMI > 30, the young surgeon unfortunately cannot avoid (for long) performing laparoscopic colectomy in this challenging group. To that end, the senior author (HDV) strongly encourages that any laparoscopic colectomy in an obese patient, even when straightforward on all other accounts (i.e., right colectomy, benign disease without inflammation or fistula), should be scheduled as an early first case without a significant number of cases to follow, whenever possible. In addition, it would be advisable for skilled assistants to be present (preferably a more experienced laparoscopic surgeon or partner) for the duration of the procedure. Such assistance improves retraction and exposure, reduces surgeon stress, and undoubtedly leads to better intraoperative decision-making and clinical outcomes for patients.

Operative Details (Table 29.2)

Table 29.2

Intraoperative considerations

• Patient positioning |

– Predisposed to increased risk of intraoperative nerve injuries from compression or traction |

– More prevalent nerve injuries due to stretch or pressure sores in obese |

• Experienced first assistant(s) |

• Additional trocar placement as needed |

– 4 to 6 trocars to assist with retraction and exposure |

• Longer ports and instruments |

– Standard (100 cm) vs. longer versions (150 cm) |

– Estimate by positioning the instruments on abdomen before actually making port site incisions |

• Avoid umbilicus for hand port |

– Umbilical location more caudal in obese population |

• Early recognition for need for conversion |

• Energy devices for intracorporeal vessel ligation |

– Shortened, thickened mesentery |

– EnSeal® or LigaSure® device |

• Complete omental dissection as necessary to facilitate specimen extraction |

• Low threshold to enlarge extraction site, due to larger specimen size |

• Port site closure device |

Positioning and Securing the Obese Patient

The weight and proportions of the obese patient impact many practical issues of laparoscopic colectomy. The operating room bed and leg stirrups must accommodate the weight of the patient, as both components have specific weight restrictions, and manufacturers offer product models to accommodate extreme patient weights. The traditional tucking of the arms of the patient may not be possible due to the breadth of the torso, and arms may need to be placed outstretched and secured (Fig. 29.4). While arm sleds enable the arms to be placed alongside of the torso, such positioning forces the surgeon and assistants further away from the operative field and causes the aforementioned ergonomic difficulties for the operating team. Additionally, more padding and attention to proper securing to the arm boards is often required to reduce peripheral nerve injuries (Videos 29.1 and 29.2).

Fig. 29.4

Positioning in a patient with a BMI of 55. (Courtesy of Conor Delaney, MD)

A system for fixation of the patient to the OR table must be reliable given the weight of the patient and the extremes of rotation and head down positioning of that must be performed to allow gravity to assist in intraperitoneal exposure (Fig. 29.5). The senior author prefers taping around the patient’s chest and operating room table three times using 3-in. wide cloth or silk tape to provide fixation (Fig. 29.6). Others describe methods including beanbags and gel pads directly beneath the patient’s torso. In any case, we suggest that, irrespective of the method, prior to prepping the patient and draping, the patient should be placed in the anticipated table positions (extreme rotation, Trendelenburg) in order for all OR personnel to observe for any movement of the patient’s torso or extremities (Fig. 29.7).

Fig. 29.5

Preparing for operating table positioning with additional padding

Fig. 29.6

Chest Strap to secure the patient to the table. 3″ silk tape may be used as an alternative

Fig. 29.7

Reverse Trendelenburg demonstrating no shift in the patient with proper securing to the table

Ureteral Stent Insertion: Selective Use

On one hand, increased retroperitoneal adipose tissue may be protective of retroperitoneal structures such as the ureter; yet, excess layers may also make visual identification more challenging. Additionally, if dissection strays from the embryologic planes, meddlesome bleeding may occur obscuring the laparoscopic perspective. Generally, good practice dictates ureteral identification prior to division of the inferior mesenteric artery or superior hemorrhoidal artery. In the case of a hand-assisted colectomy, you can palpate the ureter. Ureteral stents can also be helpful in identifying the ureter, as well as noticing a ureteral injury (should it occur) intraoperatively, but have not been shown to prevent one. A trade-off exists then with either additional time inserting stents versus meticulous dissection to establish the proper planes and identify the ureter. We feel that insertion of ureteral stents should be considered optional; though early in your experience and learning curve, this may reduce stress regarding this critical step. Exceptions where you may more strongly consider stent insertion would be cases where inflammation can be identified adjacent to the path of the ureter and iliac vessels (e.g., Crohn’s iliopsoas abscess, posterior type diverticular abscess). In the case of prior radiation, a previous left colectomy or history of pelvic surgery, you should anticipate distorted anatomy, dense adhesions, and an irregular course of the ureter. Lastly, in the case of a solitary kidney, you may be inclined to pursue preoperative ureteral stent insertion.

Ports and Exposure Techniques

Port sites must take into account the alterations in the anatomic landmarks, specifically the umbilicus, in regard to port locations (Fig. 29.8). Due to the large pannus, the umbilicus may not correlate to the traditional mid-abdominal view you may be accustomed to in normal-sized patients. In fact, for morbidly obese patients, it is often best to ignore the umbilicus altogether. On the other hand, the bony prominences of the costal margin and the iliac crest, the symphysis pubis, and the xiphoid process will not vary with abdominal girth or body mass index and will better provide guidance as to the intra-abdominal structures of interest and the best means of exposing such (Fig. 29.9).

Fig. 29.8

Low-lying umbilicus in the obese patient [Waist-to-hip Ratio (WHR) 1.2]

Fig. 29.9

Wound extraction site (hand port) based on bony prominences. (Arrow indicates the distance between the lateral trocar site and the wound extraction site)

Care must also be taken when inserting ports to consider the trajectory and angle given the torque and levering phenomena required for visualizing and working in different quadrants of the abdomen. Such torque may result in enlargement of the fascial defect and must be considered when closing the abdomen, as they may be a source of subsequent hernias and bowel obstruction. The ports themselves may also need to be extra long, especially with the super-obese (BMI > 50) patient. Generally, standard ports are of adequate length. Lastly, prior to incision and insertion, you should sketch out the port sites considered and simulate reach and position of instruments. You can then anticipate the functionality of ports and determine whether or not you have adequate length of the instruments.

Generally, the number of ports will be greater when performing a colectomy in the obese patient. Due to the lessened effect of gravity and lack of intra-abdominal room, exposure and retraction of the small bowel and its mesentery require more instruments to keep the bowel out of the way. You should have a low threshold to place additional ports to accomplish retraction of the small bowel to avoid inadvertent enterotomies, worse visualization, longer operative times, and increased frustration. In the case of left colectomy, Leroy et al. employed five and six ports liberally with one port committed purely for retracting the small bowel mesenteric root [30]. In any case, five to six ports would indicate that perhaps as many as two assistants would be required to help the operating surgeon in the case of a left colectomy. Most would agree that left colectomies present a higher degree of complexity than the simpler right colectomy, and studies examining the respective learning curves comparing right to left validate this notion [28]. Thus, when considering performing a complex colectomy in a difficult patient, such as the obese patient, ensure adequate access and exposure.

Lastly, gravity and extreme patient positioning must be maximized and dynamic. One must constantly engage the anesthesia team to alter the table position facilitating the effects of gravity and exposure. The multiple quadrants of dissection and mobilization mandate continuous alterations in the table and patient position, and the team must anticipate such frequent changes along with the implications for other accessories such as Mayo stands, instrument tables, and video monitors and towers.

Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Colectomy (HALS)

Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy represents a distinct technical variation of laparoscopic surgery. This involves insertion of the surgeon’s hand into the abdomen through an incision that ultimately serves as the wound for specimen extraction. The variation of this technique offers a pragmatic approach in the obese patient given the technical limitations and challenges described. Specifically, the surgeon’s hand provides an efficient and atraumatic means of retraction and exposure. In the case of a thickened mesentery, return of palpation improves identification of critical structures and enables safe dissection of the mesentery. Lastly, palpation restores one’s sense of proprioception and thus improves dissection in an abdominal cavity with diminished space and reduced visual cues. Difficult to validate and objectify, but perhaps the greatest attribute of the hand-assisted technique, it restores a surgeon’s confidence and sense of control where typically the obese patient humbles and frustrates surgeons. Time motion analysis study and other studies [31–33] examining the hand-assisted effect using simulators [34] indicate technical advantages of this hybrid technique as compared to conventional laparoscopic colectomy technique.

In the obese patient, HALS may in fact be preferable, although data remains sparse regarding this specific patient group. The Cleveland Clinic compared HALS versus conventional multiport laparoscopic (LAP) colectomy, finding the HALS cohort experienced significantly fewer conversions to open (3.5 % vs. 12.7 %) [34]. Additionally, incision size was larger in the HALS group, but by only 1.3 cm (7.0 vs. 5.7 cm). Postoperative outcomes including length of stay, operative time, morbidity, and mortality did not differ between the two groups. Interestingly, patients converted to open experienced worse outcomes in terms of length of stay, blood loss, and OR time when compared to successfully performed HALS or traditional laparoscopy.

However, you must also realize that HALS is unique when compared to conventional multiport laparoscopic colectomy. Specific to the obese patient, nuances exist in regard to the optimal port locations and specifically the hand port that serves the additional purposes of specimen extraction and aid in performing the anastomosis. Most importantly, the surgeon’s hand must be inserted in the most ergonomically efficient position thereby facilitating all aspects of operative technique: retraction, dissection, mesenteric isolation, and all the while, preserving laparoscopic perspective. One of the greatest criticisms of hand-assisted surgery involves the potential compromise of the laparoscopic perspective, and in the obese patient where loss of domain already reduces laparoscopic views, the configuration of hand port and laparoscopic camera location makes it all that more critical. For the occasional practitioner, hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy can be foreign and frustrating at a baseline, and it would be inadvisable to only attempt to perform a new technique in one of the most challenging circumstances (i.e., obesity).

First, placement of the hand port should enable you to reach to all quadrants of the abdomen (Fig. 29.10). This is particularly imperative as the size of the pannus makes a Pfannenstiel site challenging and in those patients with central obesity (Fig. 29.11). Therefore, the senior author prefers the midline wound for hand port. Remember, the port must facilitate all aspects of the operation including exteriorization of the specimen, assessing the mesenteric blood supply, and ultimately anastomosis of the bowel. Remembering that the umbilicus inaccurately reflects intra-abdominal anatomic structures including mesenteric position craniocaudally, it is crucial that this port be placed cranial to the umbilicus. In the case of right colectomy, this enables exteriorization of both the proximal (terminal ileum) and distal (transverse colon) limbs to reach the wound for anastomosis. Placed too inferior, the middle colic and transverse colon mesentery will limit the reach of the transverse colon. You will thereby struggle and place on tension this part of the mesentery, which ultimately could prove disastrous and cause mesenteric venous bleeding. In the case of left colectomy, the midline wound again allows for an easier exteriorization of the entire left colon, including the splenic flexure, and again allows performance of all the important steps of assessing adequate perfusion of the marginal artery and the anastomosis. In the case of left-sided colectomy—including low anterior resection—I routinely divide the marginal artery with scissors extracorporeally and allow it to bleed freely verifying pulsatile flow. Attention to this detail assures well-perfused bowel for anastomosis.