Intestinal Stomas

Marvin L. Corman

Th’ incurable cut off, the rest reforme.

—BEN JONSON, Cynthia’s Revels 5.11

The purpose of this chapter is to amplify on the methods of creating a satisfactory stoma, the means of closure, the results with these procedures, and the complications and their management.

▶ PREPARING THE PATIENT

Overcoming ignorance and fear is often the most important issue that must be addressed by the surgeon in preparing an individual for a stoma. Some patients have had unpleasant associations with ostomies through experiences and jeremiads of family and friends. Myths and misunderstandings further prejudice the patient. The surgeon must confront someone’s fear of the disease itself, the potential for complications, and, indeed, possible mortality. These issues must be addressed as part of a comprehensive rehabilitative program. It is usually very helpful to provide literature concerning the nature of the surgery and the reasonableness of living with a colostomy or an ileostomy (see also the following chapter). In addition, it is often helpful to have an individual of similar age, gender, and socioeconomic position serve to acquaint a patient with the concept of living and functioning normally with a stoma. Whenever possible, the wound/ostomy, continence (WOC) nurse should be involved with the preoperative counseling, not necessarily to provide detailed stomal care at that time, but to supply information about the wide variety of ostomy products available.1 Bass and colleagues evaluated their stoma registry, consisting of 1,790 patients, for early and late complications with respect to whether they underwent stomal marking (see later) and education by the WOC nurse.17 The difference in the total number of complications between the two groups was found to be statistically significant, confirming that preoperative evaluation by a WOC nurse, marking of the skin site, and providing patient education contribute to reduction of adverse outcomes. Nugent and coworkers (Southampton, United Kingdom) concluded in their questionnaire involving 391 patients that “improved preoperative assessment and counseling with longer follow-up by the stoma department would be helpful in the management of these patients and probably would contribute to improvement in the quality of their lives.”174 Moreover, in a report by Chaudhri and colleagues, stoma education was found to be more effective if undertaken in the preoperative setting.43 They noted, “It results in shorter times to stoma proficiency and earlier discharge from the hospital. It also reduces stoma-related interventions in the community and has no adverse effects on patient well-being.”

Stomal Marking

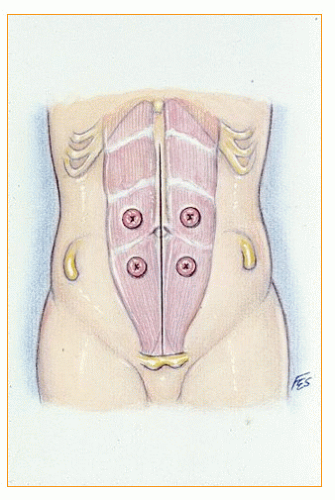

The location of the stoma has a direct bearing on subsequent ostomy management. Establishment of the stomal site prior to surgery is usually the responsibility of the surgeon, but in many instances may be delegated to a trained WOC nurse (Figure 31-1). Proper location of the colostomy or ileostomy can often prevent complications, such as prolapse, hernia, and skin problems.53,115

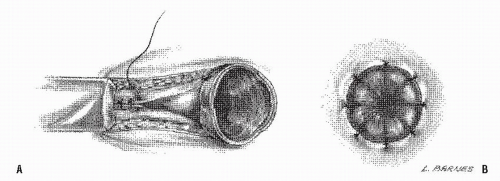

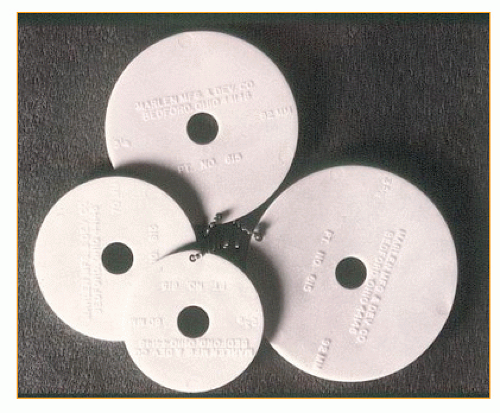

FIGURE 31-1. Four different sized templates of faceplates used by WOC nurses for marking the optimal stomal site. |

The groin, the waistline, the costal margins, the umbilicus, skin folds, and scars frequently interfere with appliance management. It is advisable to leave a 5-cm margin of smooth skin around the stoma. The stoma should always be placed at the summit of the infraumbilical bulge and within the rectus muscle. When the site is being marked, it is helpful to have the patient lie in the supine position and tense the abdominal muscles. This allows one to feel the lateral border of the rectus muscle. A triangle is formed by drawing an imaginary line from the umbilicus to the pubis, one from the umbilicus to the anterosuperior iliac spine, and another from the pubis to the anterosuperior iliac spine (the inguinal ligament; see Figure 29-39). The stoma usually should be in the center. The faceplate should be taped over the site and the patient should stand, sit, and bend with the faceplate in place. Slight adjustments may be required because of interference from skin creases and adiposity.

Another factor to consider is the patient’s preference for clothing style, especially where the belt is worn, because stomas ideally should be placed below the waist and preferably below the belt line. Should an individual require two stomas, the new opening must be placed either above or below the existing one. Occasionally, it may be necessary to keep a faceplate in place for 24 hours to ensure the patient’s subsequent comfort and ease of movement. This is especially true when the abdomen contains multiple scars. My own preference is simply to scratch a mark onto the proposed location (see Figure 29-40). The use of a pen is not advised because such markings are often obliterated during the abdominal preparation.

If a site is not selected until the patient is in the operating room, what is perceived to be an ideal location may subsequently present a difficult management problem. The outer margin of the faceplate may appear at the waistline or in the groin, or the stoma may be found on the undersurface of the infraumbilical bulge, making it impossible for the patient to fit the skin barrier properly and to center the pouch. At the very least, a flange can be used that corresponds to the diameter of the faceplate of an appliance in order to identify the site and to give some degree of assurance.

The aforementioned considerations are applicable to all intestinal stomas—ileostomy, sigmoid colostomy, transverse colostomy, and urinary conduit (Figure 31-2). However, it is unfortunate that what we surgeons strive for may be difficult to achieve—namely, preoperative determination of the proper site for the stoma. Because patients are commonly admitted the day of surgery in the United States, preoperative counseling and stomal location often are relegated to a secondary role because of other, important concerns, such as anesthetic clearance, operative consent, site verification, confirmation of the presence of a myriad of legal and medical paperwork on the chart—the list seems endless. This is why every effort should be made to accomplish this task at a time when one is not attempting to respond to the demands and concerns that are inherent to the preoperative preparation process.

▶ LAPAROSCOPIC-ASSISTED STOMAL CREATION

One of the indications for performing minimally invasive surgery, that is, laparoscopic bowel surgery, is the creation and closure of intestinal stomas (see Chapter 19). A number of papers have been published that attest to the fact that this approach is well tolerated and can be performed safely and effectively.76,104,113,147,173,200,228,232,272 Obvious advantages include the avoidance of a laparotomy while still maintaining the ability to precisely identify and orient the pertinent bowel segment. The approach to performing these techniques is discussed in Chapter 19.

▶ COLONOSCOPIC-ASSISTED STOMAL CREATION

Another minimally invasive approach to the creation of a colostomy that has been proffered is to insert a colonoscope in order to identify the site in the colon that could permit (by means of transillumination) the appropriate site for creating the stoma.150,170 Of course, one may still do the entire stomal

construction through the same opening from which the subsequent colostomy or ileostomy will be created, especially in someone with a favorable body habitus.

construction through the same opening from which the subsequent colostomy or ileostomy will be created, especially in someone with a favorable body habitus.

▶ PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC COLOSTOMY

A modification of colonoscopic-assisted colostomy or cecostomy is analogous to that of percutaneous gastrostomy and that of percutaneous endoscopic colostomy. A colonoscope is passed, and a percutaneous colostomy tube is inserted into the bowel lumen. One must be concerned about the risk of fecal contamination or rupture of the thin colon wall, a potentially catastrophic consequence when there is no ready means available to limit the amount of spillage. Furthermore, with this minimally invasive alternative, the fecal stream is not truly diverted; therefore, this application is very limited. Heriot and colleagues employed this approach as an alternative to a conventional colostomy in a single patient with obstructed defecation.106 It has also been used for the management of sigmoid volvulus58 and for colonic pseudoobstruction.33,185

▶ SIGMOID COLOSTOMY

The most common indication for performing a permanent sigmoid colostomy is carcinoma of the rectum. Other possible indications for either a permanent or a temporary stoma include diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, congenital anomalies, anal incontinence, and colorectal trauma. Certainly, the most frequent reason for performing a sigmoid colostomy today is the Hartmann’s procedure for sigmoid diverticulitis, although the stoma is generally intended to be temporary.

The historical aspects of the evolution of colostomy are discussed in Chapters 23 and 24. See also comprehensive reviews on the subject by Cromar,56 Dinnick,59 and McGarity.154 The technique for creating a satisfactory end-sigmoid colostomy has been described previously as it pertains to the abdominoperineal resection for carcinoma of the rectum (see Figures 24-68,24-69 and 24-70). As has been repeatedly emphasized, it is important that the colon be brought through the split rectus muscle and sutured to the skin without tension. Ideally, redundant colon should be excised in order to permit a satisfactory irrigation should the patient so elect and to minimize bowel symptoms. If the surgeon elects to perform a paramedian incision, then he or she must create the stoma either in a pararectus location or bring the colostomy through the wound. Neither of these methods is appropriate unless there literally is no other place to put it. A pararectus colostomy predisposes to peristomal hernia (see later).

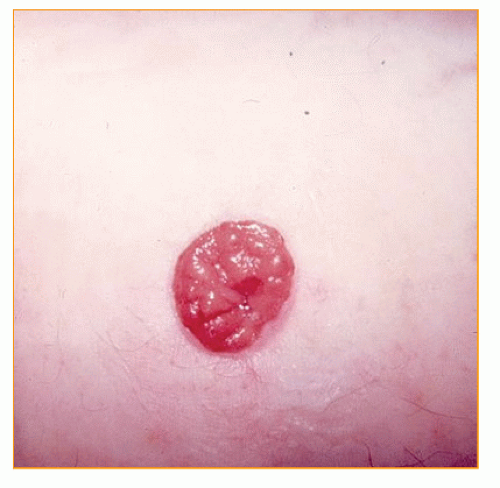

A “flush” colostomy can be performed with reasonable safety because the colostomy effluent is noncorrosive, but such a technique is not advised. With the patient’s possible weight gain, the stoma may retract. This makes appliance management more difficult. Hence, the stoma should be permitted to pout slightly, but not to the extent of a conventional ileostomy (Figure 31-3). When the colostomy has been created, a transparent drainable bag is placed before the patient leaves the operating room (see Figure 32-5). This permits visualization of the stoma during the immediate postoperative period, and the viability of the bowel can be determined on a continual basis. Usually, when the colostomy begins to function (after 2 or 3 days), the bag is removed and the stoma and skin are carefully inspected.

Complications

The principles of proper stomal construction have already been outlined. The bowel must be drawn through the abdominal wall without tension; it should be brought through the split rectus muscle; it must be sutured primarily to the skin; and the viability of the end of the colon must be clearly demonstrated.249 Although no method guarantees that subsequent complications will be avoided, attention to the said principles will minimize the risks. But the fact of the matter is that most colostomy complications are preventable.

Ischemia and Stomal Necrosis

Ischemia and stomal necrosis are obviously due to inadequate blood supply. This is more likely to develop if the ascending branch of the left colic artery is not preserved, a consequence of high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery (on the aorta). Another possible source for compromise of the blood supply occurs if the meandering artery of Drummond has been divided or if collateral circulation from the middle colic vessels is inadequate.

Recognition of stomal ischemia should not be difficult. If the mucosa looks blue, it probably is ischemic. Occasionally, after a difficult abdominoperineal resection, one may be less compulsive in creating the colostomy or perhaps somewhat less concerned about the possible nonviability of the stoma. It is better to reopen the abdomen to free a further length in order to effect a satisfactory stoma at the time of the resection than to have to return the patient to the operating room several days or weeks later. Many surgeons prefer to always take down the splenic flexure when a left-sided colostomy is planned in order to create adequate bowel length, preserve blood supply, and avoid tension. Splenic flexure mobilization is one of the major benefits of combining laparoscopy with an open operation (see Chapter 19). The philosophy expressed by the

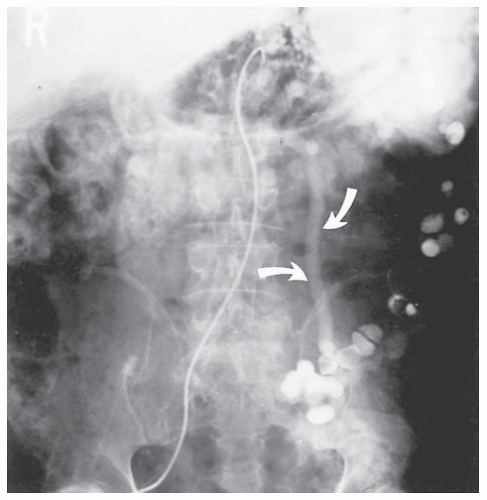

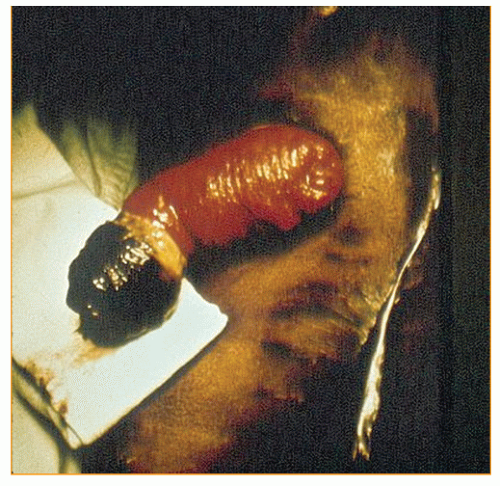

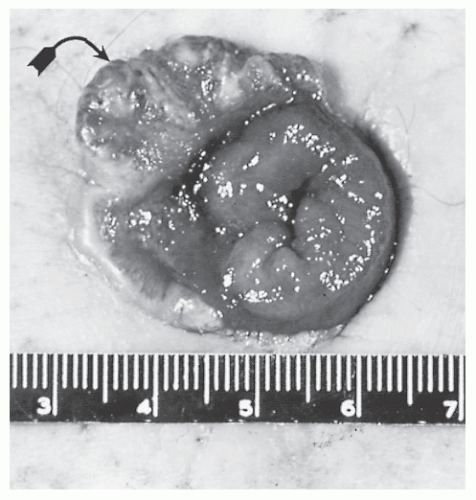

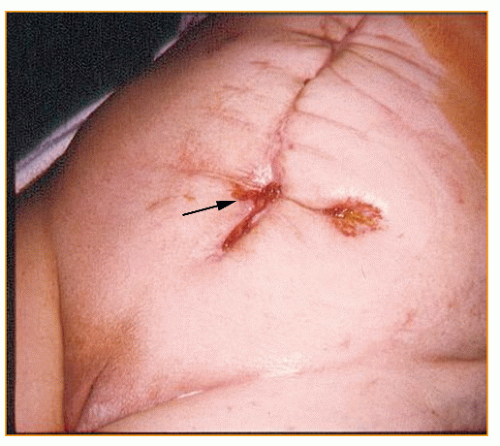

statement, “It looks a bit dark, but it will probably be all right,” is delusional. If the stoma is nonviable, the bowel may retract into the peritoneal cavity. Peritonitis can ensue and necessitate emergency surgical intervention. Equally concerning is the situation illustrated in Figure 31-4. The sigmoid colostomy has retracted, and the stool presents in the lower portion of the abdominal incision, tracking subcutaneously from the original opening in the rectus fascia. In a less ominous consequence, the stoma may separate from the skin at the area of nonviability, with a resultant stricture (Figure 31-5).

statement, “It looks a bit dark, but it will probably be all right,” is delusional. If the stoma is nonviable, the bowel may retract into the peritoneal cavity. Peritonitis can ensue and necessitate emergency surgical intervention. Equally concerning is the situation illustrated in Figure 31-4. The sigmoid colostomy has retracted, and the stool presents in the lower portion of the abdominal incision, tracking subcutaneously from the original opening in the rectus fascia. In a less ominous consequence, the stoma may separate from the skin at the area of nonviability, with a resultant stricture (Figure 31-5).

FIGURE 31-4. Sigmoid colostomy. Retraction with feces draining entirely from the abdominal wound (arrow). |

Management

Many patients are able to cope reasonably well even with a severely stenotic colostomy. Formed stool may be able to pass without difficulty, and appliance management is rarely a problem. However, if the individual cannot cope with symptoms associated with the retraction or stenosis, revision is required. Dilatation alone of a skin-level stenosis is not recommended because it usually re-strictures. The trauma from manipulation may also cause hemorrhage and further inflammatory reaction and may actually worsen the condition.

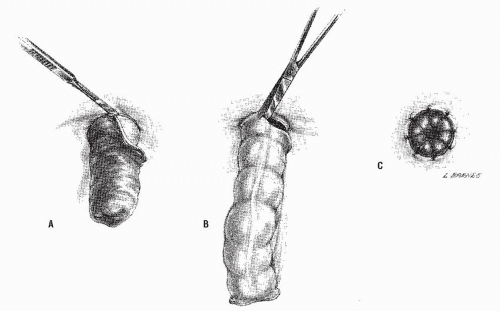

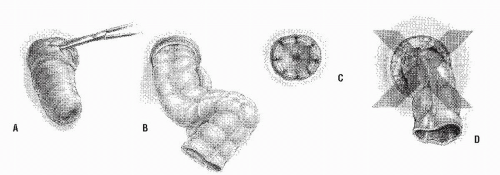

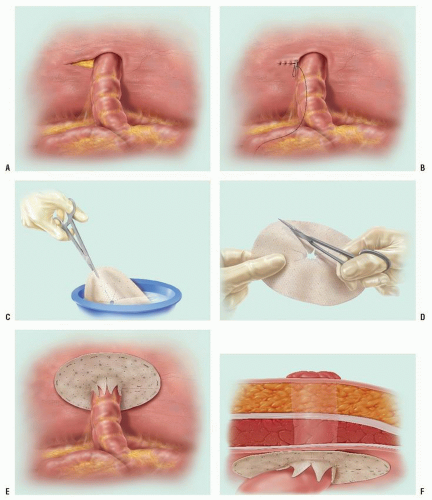

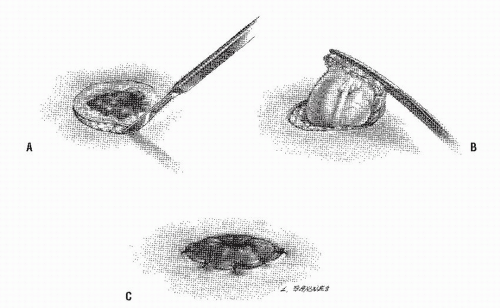

A laparotomy with colostomy resection and the creation of a new stoma are necessary if adequate length cannot be established by a limited approach. However, an attempt should be made to circumcise the colostomy, to free up the bowel, and to re-suture it. The technique is illustrated in Figure 31-6. The application of the circular

stapler for resection of a colostomy stricture has also been suggested.193

stapler for resection of a colostomy stricture has also been suggested.193

FIGURE 31-6. Revision of retracted or stenotic colostomy. A: Skin is incised. B: Bowel is mobilized. C: New stoma is matured. |

Rarely, the stenosis occurs at the fascial level. This is usually due to an inadequate opening in the fascia itself or to vascular compromise. Treatment usually requires mobilization of the bowel, enlargement of the opening in the fascia, and re-suturing of the colon.

Results

Only a limited number of papers have been published in recent years. Park and coworkers reporting the Cook County Hospital experience noted that 34% of 553 responding patients had stomal complications (stenosis, 2%) and emphasized the importance of preoperative stoma site marking.178 Allen-Mersh and Thomson reviewed their experience with the surgical treatment of colostomy complications, identifying 65 patients who underwent revision due to stenosis.9 This represented 53% of the operative stomal problems. Local excision of the scar tissue at the mucocutaneous junction was associated with a 61% success rate for relief of their symptoms.

Paracolostomy Abscess and Perforation

Paracolostomy abscess is an unusual postoperative complication. It should be a particularly unlikely event if the stoma is placed outside of the abdominal incision. The problem is more likely to be seen after an ileostomy when sutures may be placed too deeply and penetrate the bowel lumen at the time of eversion (see later). Another possible cause of a parastomal abscess in a patient who has undergone an ileostomy is recurrent Crohn’s disease.

If the colostomy retracts and there is fecal contamination in the subcutaneous tissue, an abscess can result. However, by far the most common reason for paracolostomy abscess is the performance of an improper irrigation technique (see later and Chapter 32). Either the irrigating fluid or the device used for insertion into the stoma may perforate the bowel.

Symptoms include an unrewarding irrigation, which is often associated with immediate abdominal pain.117 Obvious sepsis may supervene with evidence of cellulitis of the abdominal wall. If the process dissects into the peritoneal cavity or had started within the abdomen, it can lead to generalized peritonitis. Predisposing factors for the development of this complication include the presence of a pericolostomy hernia, alcoholism, psychological disturbance (e.g., self-mutilation), and, of course, carelessness. A case of burn and stricture of the ostomy has been reported due to the accidental insertion of boiling water for irrigation.84

Management

Treatment usually requires laparotomy and relocation of the colostomy, but Reynolds and colleagues reported satisfactory management by means of adequate surgical drainage and intravenous hyperalimentation or an elemental diet.196 In their experience, no proximal diversion was undertaken. However, in my own experience with this complication, usually in patients who develop a bowel perforation secondary to irrigation, this is a major septic problem requiring an urgent operation and extensive debridement, drainage, stomal relocation, and, in some situations, a proximal colostomy or ileostomy. Gomez and Rosenthal recommended a semisynthetic biologic dressing (Biobrane) as a skin substitute when colostomy perforation caused massive abdominal wall tissue loss.92

Results

Isa and Quan reviewed the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience with colostomy perforation.117 This was observed 10 times in a 10-year period ending in 1975, almost historical data at this date. In nine cases, the cause of the perforation was irrigation of the colostomy, and in one instance a barium enema examination. Barium enema perforation can usually be avoided by the use of a cone tip (see Figure 5-17B) or other device.212 As previously discussed, the use of a balloon catheter should be vigorously condemned.

Hemorrhage

Colostomy hemorrhage is extremely unusual in the immediate postoperative period. However, in the event of underlying portal hypertension from cirrhosis secondary to alcohol ingestion or sclerosing cholangitis, the mucosa of the exposed bowel is predisposed to the possibility of considerable bleeding (Figure 31-7). This rare complication is more commonly seen in someone with an ileostomy, usually because of the association between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), sclerosing cholangitis, and portal hypertension (see Figure 31-65). Roberts and colleagues identified 12 patients from the Lahey Clinic who had bleeding from stomal varices; all but one had ulcerative colitis.198

The bleeding originates from enterostomal varices located at the level of the mucocutaneous junction, a consequence of communication with the high-pressure venous network of the superior and inferior mesenteric veins.50,198 Erosion of the varix or trauma can exacerbate the hemorrhage.

Handschin and coworkers (Zurich, Switzerland) reported a man with portal hypertension and recurrent bleeding from varices in a sigmoid colon stoma.101 They localized the bleeding source through contrast-enhanced threedimensional magnetic resonance angiography. The bleeding was subsequently controlled by means of the implantation of a transjugular intrahepatic shunt.

Treatment

Direct pressure is usually the initial approach. Other alternatives such as suture ligation of the bleeding areas, beta blockade, and injection sclerotherapy (by means of polidocanol, phenol [5%] in almond oil, or tetradecyl sulfate) have all been tried with varying degrees of success.70,107,166 Goldstein and colleagues concluded in their review that control of major stomal hemorrhage by local measures is often ineffective and that portosystemic shunting may be required.90

Beck and associates performed mucocutaneous disconnections in 9 of their 11 patients who failed with one or more of the lesser options.20 The dissection is carried down to the level of the fascia, and the varix is divided and ligated. With a follow-up of up to 4.6 years, two individuals required reoperation for hemorrhage. The alternative approach employed by this group was stomal relocation (two patients, one failure).

Prolapse

An end colostomy prolapse is an uncommon complication and is especially unusual following abdominoperineal resection. Chandler and Evans identified only 2 patients of 217 who underwent the procedure (less than 1%).42 The problem occurs much more frequently in those who have undergone a loop colostomy (see later) than in those with an end stoma. The etiology of the problem may be an oversized opening in the abdominal wall, a redundant sigmoid loop leading to the stoma, sudden increased abdominal pressure (e.g., straining or coughing), or a rigid appliance worn with a tight belt.135 The condition is frequently associated with a paracolostomy hernia. Adequate fixation of the mesentery and bowel to the peritoneum has been suggested as a means for preventing this complication, but I do not agree with this view. Sometimes those who develop endsigmoid colostomy “prolapse” have a stoma that was initially created too long (Figure 31-8). This technical error, in combination with several other predisposing factors, such as the presence of a redundant loop of sigmoid colon, an asthenic patient, or an individual with chronic obstructive lung disease, tends to create the problem.

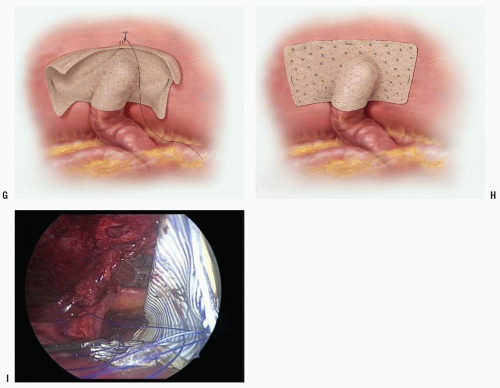

Treatment

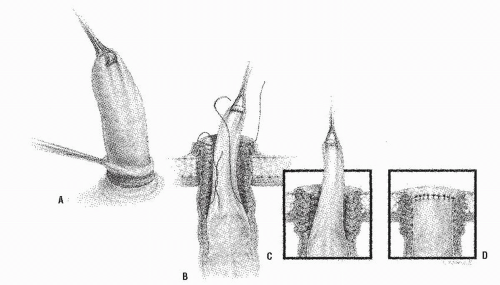

In the absence of an associated hernia, treatment of a prolapse usually does not require a laparotomy. If the prolapse occurs relatively soon after it has been constructed, the colostomy is circumcised at the mucocutaneous junction and the bowel liberated, resected, and re-sutured (Figure 31-9). If the prolapse occurs several months after the initial operation, the incision should be made into the mucosa rather than into the skin (Figure 31-10A). The blood supply from the adjacent skin will be sufficient to maintain viability of the stoma, and an anastomosis is actually effected between the distal colon and the residual mucosa (Figure 31-10C). This technical detail is an important concept to remember because if the skin is incised, too large an opening will be created when the stoma is subsequently matured (Figure 31-10D). It is important to liberate as much intraabdominal colon as possible and to resect it in order to avoid recurrent prolapse. With a particularly mobile colon, one may actually ultimately be creating an end-transverse colostomy in the left iliac fossa.

Abulafi and colleagues offer a unique approach to the management of colostomy prolapse, a modification of the Delorme procedure (see Chapter 21).5 The submucosa is infiltrated with a dilute adrenaline solution, and a mucosal incision is made 10 to 15 mm from the mucocutaneous junction (Figure 31-11A). Following separation of the mucosa for the full length of the prolapse, six to eight plicating sutures are placed in the muscular wall from the mucocutaneous junction to the apex (Figure 31-11B,C). The redundant mucosa is excised and the mucosa re-sutured (Figure 31-11D).

Acute stomal prolapse is uncommon and requires immediate attention to reduce it. This is usually accomplished by gentle pressure such as has been described in the chapter on rectal prolapse (see Chapter 21). As with osmotic therapy through the use of sugar applied to the prolapse, the same treatment has been demonstrated to be effective for acute, irreducible stomal prolapse.72

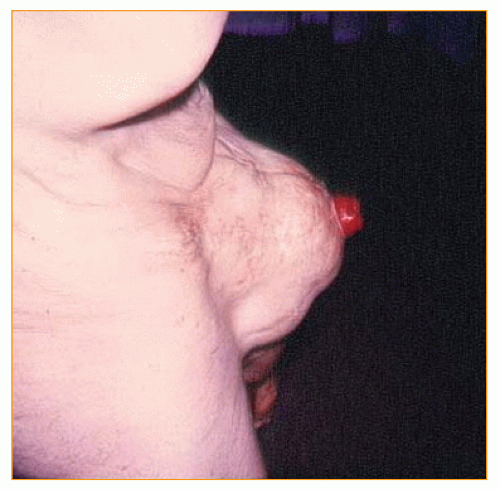

Rarely, sigmoid colostomy prolapse may produce compromise of the blood supply to the bowel and gangrene of the stoma (Figure 31-12). Depending on the level of involvement, resection of the necrotic bowel may be accomplished without a laparotomy, or alternatively an intra-abdominal procedure may be required. If a prolapse is associated with a paracolostomy hernia, relocation of the stoma may be necessary (see the following section).

Results

The previously mentioned report of Allen-Mersh and Thomson identified 16 individuals who underwent surgery for colostomy prolapse.9 This represented 13% of the stomal complications requiring operation. Local fixation procedures failed to prevent recurrent prolapse in two-thirds.

Parastomal Hernia

Parastomal hernia is the most common late complication of abdominoperineal resection. Between 87,000 and 135,000 intestinal stomas (ileostomy and colostomy) are created each year. It is estimated that one-half of these will be permanent stomas, of which 30% to 50% (i.e., 20,000 to 35,000) will then develop parastomal hernias. In a prospective audit of individuals attending a routine outpatient clinic at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, 90 consecutive patients were assessed for the presence of a parastomal hernia.183 One-third were found to harbor this complication. As mentioned earlier, the usual reason for development of this problem has been felt to be the placement of the stoma in a pararectus location. Sjödahl and colleagues studied the location of the stoma in relation to the rectus abdominis muscle, noting that

the prevalence of parastomal hernia was 2.8% in those brought through the muscle and 21.6% in those placed laterally, a highly significant difference.221 The St. Mark’s Hospital group studied the long-term complication rate of end-sigmoid colostomy and found that the crude and actuarially corrected risks of paracolostomy complications in 203 patients at 13 years were 51.2% and 58.1%, respectively.145 They concluded that siting the stoma through the rectus muscle did not reduce the risk of hernia. However, an extraperitoneal course was associated with a significantly lower risk of herniation when compared with a transperitoneal course. The authors opined that parastomal hernia is technically avoidable.145 Other possible causes of paracolostomy hernia include locating the stoma in the incision itself and the creation of too large an opening in the abdominal wall (Figures 31-13,31-14 and 31-15). Some surgeons are sufficiently nihilistic that they believe

this complication is inevitable if the patient survives long enough—a theory impossible to dispute. Certainly, weight gain, the effects of the aging process, other systemic diseases, nutritional problems, and many other factors may predispose to the development of this problem. Symptoms may be only those related to esthetic concerns expressed as the unsightly bulging. Other complaints include problems with appliance management (leakage, soiling, and detachment), pain, and rarely obstructive symptoms (due to bowel incarceration adjacent to the stoma). The diagnosis is usually self-evident, but computed tomography (CT) is felt by some to be a valuable tool in determining the true incidence of parastomal hernias. It will also aid in diagnosing occult parastomal hernias.46

the prevalence of parastomal hernia was 2.8% in those brought through the muscle and 21.6% in those placed laterally, a highly significant difference.221 The St. Mark’s Hospital group studied the long-term complication rate of end-sigmoid colostomy and found that the crude and actuarially corrected risks of paracolostomy complications in 203 patients at 13 years were 51.2% and 58.1%, respectively.145 They concluded that siting the stoma through the rectus muscle did not reduce the risk of hernia. However, an extraperitoneal course was associated with a significantly lower risk of herniation when compared with a transperitoneal course. The authors opined that parastomal hernia is technically avoidable.145 Other possible causes of paracolostomy hernia include locating the stoma in the incision itself and the creation of too large an opening in the abdominal wall (Figures 31-13,31-14 and 31-15). Some surgeons are sufficiently nihilistic that they believe

this complication is inevitable if the patient survives long enough—a theory impossible to dispute. Certainly, weight gain, the effects of the aging process, other systemic diseases, nutritional problems, and many other factors may predispose to the development of this problem. Symptoms may be only those related to esthetic concerns expressed as the unsightly bulging. Other complaints include problems with appliance management (leakage, soiling, and detachment), pain, and rarely obstructive symptoms (due to bowel incarceration adjacent to the stoma). The diagnosis is usually self-evident, but computed tomography (CT) is felt by some to be a valuable tool in determining the true incidence of parastomal hernias. It will also aid in diagnosing occult parastomal hernias.46

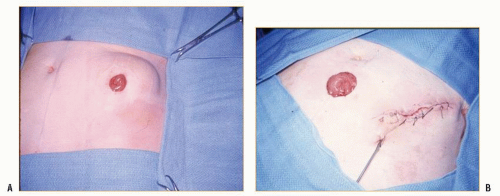

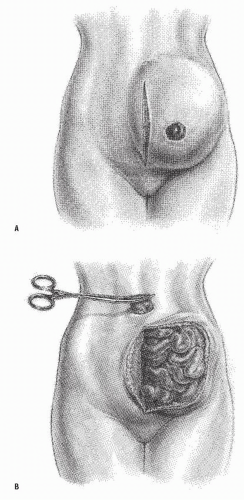

FIGURE 31-13. Massive paracolostomy hernia. Note that the stoma had been brought through the left paramedian incision. |

FIGURE 31-14. Paracolostomy hernia. Atrophic skin is the only covering of the abdominal cavity. The stoma is at the proximal aspect of the defect. |

Treatment

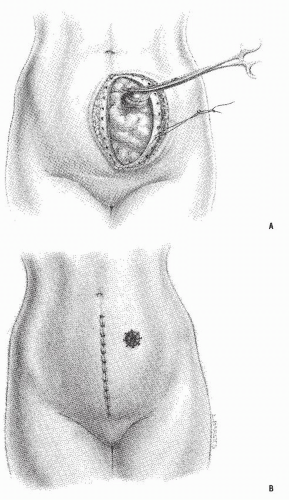

The choices of operative approaches to the repair of a peristomal hernia are usually dictated by its size. Relatively small defects may be repaired by direct suture, circumcising the colostomy, closing the abdominal wall, and re-maturing the stoma (Figure 31-16). This technique, suggested by Thorlakson,243 may be employed with two caveats: if the colostomy has been created in the proper location, that is, through the split rectus muscle, and if there is only a small defect. If a small hernia is present in conjunction with an improperly located stoma, the colostomy should probably be relocated. Such relocation can sometimes be accomplished by an intraperitoneal tunnel method, closing the defect at the original site (Figure 31-17). If the rectus location is still available, this is the optimal site. If not considered appropriate, one has three options for potential placement: use the opposite side of the abdomen, place the stoma at the umbilicus, or employ a mesh replacement by one of a number of approaches.

The use of the umbilical site is not a unique concept. Some surgeons prefer to create the colostomy in the umbilicus initially. Raza and colleagues evaluated 101 patients in whom they performed such a stoma.194 They strongly supported the concept of this location because of their low incidence of complications: only four patients required

reoperation. There were no parastomal hernias and no prolapses in their experience. If an umbilical colostomy is created, the technique of construction is essentially the same, but it is important to remove all of the skin that tends to turn inward. Turnbull (see Biography) commented that this is why the Almighty created the umbilicus—namely, as a backup resource for the placement of a stoma. It is generally preferred to use the patient’s own tissue for repair if one can achieve a successful result, but reconstruction of larger hernias requires insertion of prosthetic material. This may be accomplished either by the open method or laparoscopically.2,37,124,165,192,205,230,237

reoperation. There were no parastomal hernias and no prolapses in their experience. If an umbilical colostomy is created, the technique of construction is essentially the same, but it is important to remove all of the skin that tends to turn inward. Turnbull (see Biography) commented that this is why the Almighty created the umbilicus—namely, as a backup resource for the placement of a stoma. It is generally preferred to use the patient’s own tissue for repair if one can achieve a successful result, but reconstruction of larger hernias requires insertion of prosthetic material. This may be accomplished either by the open method or laparoscopically.2,37,124,165,192,205,230,237

In repairing the hernia, some surgeons prefer to maintain the stoma at the original location, using the mesh around the colostomy as an onlay, an inlay, or an underlay (sublay) repair. The last technique is my personal preference. Others bring the bowel through the middle of the material, the “keyhole” method (Figure 31-18). In my opinion, relocating the stoma elsewhere is preferable if it can be accomplished (Figure 31-19). In the Sugarbaker modification, an underlay mesh is placed with the stoma exiting at the lateral border of the mesh.231 Overlap is achieved with the mesh lying on the distal few centimeters of the stoma. Figure 31-20 demonstrates various techniques for mesh implantation, including that of a minimally invasive approach (see later). Tekkis and colleagues use a Thorlakson method at the site of the stoma, incorporating an incomplete circumferential mesh.237

There is always the possibility of infection and persistent drainage if a nonabsorbable prosthetic material is placed in a contaminated field, but this is uncommon and usually not a concern. A number of products are available for implantation. Sepramesh (a polypropylene composite) has the advantage of limiting adhesion formation to the implant. Others advocate porcine dermal collagen (Permacol) and other bioprosthetic meshes to perhaps minimize the risk of persistent infection but at the cost of (again “perhaps”) an increased recurrence rate.64,116,244 Other choices include polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF—Tecaflon),24 polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE),141,227 polypropylene (Marlex, Surgipro, Surumesh),110 and Gore-tex.

Moisidis and coworkers simulated the “stresses” imposed on Marlex mesh and found that the hole tends to enlarge and to become distorted.165 They suggest that the cut margins should be reinforced with a polypropylene purse-string suture in order to stabilize the opening. Hofstetter and coworkers describe a technique using PTFE mesh in 13 patients, wherein the stoma is fully mobilized, but the mucocutaneous anastomosis is not disrupted.112 The abdominal wall repair is reinforced with a 10-cm × 12-cm sheet, with the mesh incised and wrapped around the bowel. The hole that is created in the mesh is described as having an eight-pointed, starshaped configuration.

Laparoscopic Approach.

In recent years, there has been an interest in effecting repair by means of a laparoscopic technique.27,186,257 Laparoscopic hernia repair is considered by some to be a less invasive procedure that may be used for incisional hernia, as well as parastomal hernia. The technique involves access from a site not involving the stoma or scars (see principles discussed in Chapter 19). The procedure generally requires three trocar sites: one for the endoscope and the others for the dissection. During a laparoscopic incisional hernia repair, the hernial sac is pushed inside the abdominal cavity. The defect is covered with a mesh graft placed in an underlay fashion.

There are two types of laparoscopic parastomal techniques: one through the mesh or keyhole approach (similar to that shown in Figure 31-18) and the second, the so-called Sugarbaker modification. In keyhole repairs, the parastomal hernia is fixed with an intraperitoneal mesh, with the creation of an opening to allow the intestine through. In the “Sugarbaker” or “modified Sugarbaker” repair, the mesh is also placed intraperitoneally but without creating an opening. The mesh covers the defect and surrounds the bowel as in the previously discussed open technique. Transfacial sutures are recommended to be placed along the side of the stoma.

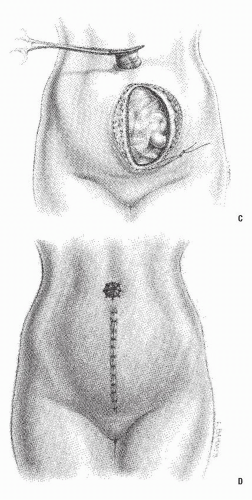

FIGURE 31-19. Underlay repair of large parastomal hernial defect with mesh, transplanting stoma. A: Incision. B: Relocation of stoma to the umbilicus. (continued) |

FIGURE 31-19. (continued) C: Placement of mesh, anchoring it to the undersurface of the abdominal wall with interrupted, monofilament, nonabsorbable sutures. D: Wound closure and maturation of stoma. |

Results

There is a justifiable concern about interpreting the results following repair of parastomal hernias. Follow-up is often quite limited, the series generally are very small, and there is a nonexistent randomized, controlled experience. Allen-Mersh and Thomson identified 42 individuals who underwent repair of paracolostomy hernia, an incidence of 34% of all operative stomal complications.9 Local repair failed in 47%, but re-siting the stoma to the umbilicus or to the right side of the abdomen was more successful (57%). Re-siting to the same (left) side was associated with a failure rate of 86%.

Alexandre and Bouillot used a Dacron prosthesis in 10 patients with pericolostomy hernia.8 There were no infections and no mortality, but there was one recurrence. In a retrospective review by Rubin and colleagues involving 80 patients who underwent parastomal hernia repairs, the investigators concluded that stomal relocation is superior to that of direct fascial repair.207 Furthermore, for those that recur, they found that the use of prosthetic material is the most successful method for effecting cure. Cheung and associates retrospectively reviewed their 43 patients who underwent repair of parastomal hernia.44 The overall recurrence rate was 40%. Stelzner and coworkers reviewed 20 patients who underwent PTFE repair for large stomal hernias.227 There were no infections, and there were three recurrences (mean follow-up, 3.5 years). In a literature review on the use of mesh repairs for parastomal hernias, Tekkis and colleagues were able to identify 72 cases.237 The overall failure rate due to recurrence or mesh-related sepsis was 8.3%. Carne and colleagues conducted a search using the Medline database and concluded that no technical factors related to construction have been shown to prevent herniation.39 However, Jänes and coworkers undertook a prospective clinical trial in which 54 individuals undergoing permanent colostomy were randomized to have a conventional stoma or a mesh placed in a sublay position.118 No infection or fistula was observed. At the 12-month followup, parastomal hernia was present in 8 of 18 without a mesh and none of 16 patients in whom the mesh was used.118 Ellis retrospectively reviewed 20 patients who underwent a bioprosthetic repair through a midline incision.64 There were no infections, but two recurrences were noted at a median follow-up of 18 months (range, 12 to 54). Berger and Bientzle undertook laparoscopic repair of 66 patients with parastomal hernias with “promising results.”24

Unfortunately, many of colostomy patients are elderly or represent a high risk for a major abdominal operation, and relocation and mesh implant indeed comprise a major procedure. There may be no recourse for some except to use some

form of abdominal support. Fortunately, many individuals are relatively asymptomatic180; hence, operative intervention is not necessarily a requisite.

form of abdominal support. Fortunately, many individuals are relatively asymptomatic180; hence, operative intervention is not necessarily a requisite.

Prophylactic Mesh Insertion.

A number of publications have appeared in recent years on the insertion of a mesh at the time of stomal construction, both open and laparoscopic, on a prophylactic basis to “strengthen the colostomy outlet” and to prevent a subsequent parastomal hernia.19,86,118,143,146,148,255 Bayer and coworkers reported 43 patients with no evidence of hernia after a 4-year follow-up by means of the prophylactic placement of polypropylene mesh.19 Gögenur and coworkers also placed polypropylene mesh in an onlay position at the primary operation in 25 patients.86 At a median follow-up of 1 year, no infections or early complications were noted (there was one unrelated death). Two patients developed parastomal hernias, one at 6 and the other at 12 months.

Recurrent Disease

Recurrence of the primary condition may develop at the site of the stoma. This is usually seen in patients who have undergone abdominoperineal resection or a diversionary colostomy for IBD (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease). The mucosa appears edematous and friable, bleeds easily, and may be granular or ulcerated. Medical management of IBD may resolve the inflammation and ameliorate the patient’s complaints. However, because of diarrhea and the inability to maintain an appliance satisfactorily, a more extensive bowel resection and possible ileostomy may be required (see Ileostomy Complications).

Recurrent malignancy may occur at the site of the colostomy and is a rare and potentially fatal complication (Figure 31-21). This may be due to tumor implantation at the time of the resection or to an inadequate margin of resection. Another possibility is that it may actually represent a second primary lesion. For example, epidermoid carcinoma of the parastomal skin has also been reported.83 Radical resection of the involved area including part of the abdominal wall with relocation of the stoma is the recommended treatment.

TABLE 31-1 Complications of Terminal Colostomy (251 Patients) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results of Colostomy Creation

Whittaker and Goligher reviewed their experience with colostomy following abdominoperineal resection of the rectum in 251 patients who survived for at least 2 years.263 Upon comparison of extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal colostomy, it appeared that the complication rate was higher with the latter technique (see Figures 29-44 and 29-45 as applied to ileostomy, but the principle is the same). The difference, however, was not statistically significant. Table 31-1 demonstrates the results of this study. It can be appreciated that colostomy construction is associated with a high incidence of complications. Almost 50% of the patients in this series (those who survived for at least 2 years) developed a stomal problem. One can only conjecture that had the patients been followed for a longer period, the complication rate would be higher.

Porter and colleagues reviewed their experience with 130 end colostomies, followed for an average of 35 months.187 There were 69 complications in 55 patients (44%). These included 11 strictures, 9 wound infections, 14 hernias, 9 small bowel obstructions, 4 prolapses, 2 abscesses, and 1 parastomal fistula. Mealy and associates reviewed 120 patients who underwent colostomy both on an elective and an emergency basis.157 Colostomy-related morbidity included stenosis, retraction, prolapse, and hernia formation. These were observed in 19.2% of their 120 patients. There was no difference in incidence between the emergency and elective groups.

Marks and Ritchie reviewed their experience with complications following abdominoperineal resection for carcinoma

of the rectum during the period 1968 through 1972 at St. Mark’s Hospital.149 Of the 227 patients who formed the basis of this study, three died in the postoperative period. By far, the most common stomal problem encountered was hernia, which occurred in 23 patients, approximately 10%. It was felt that the cumulative risk of developing a paracolostomy hernia in the sixth postoperative year was approximately 33%. The authors believed that extraperitoneal colostomy seemed to offer some protection against herniation. The other reported complications included retraction, stenosis, abscess, and prolapse. The cumulative incidence of all these stomal complications was approximately 7%. This report and others confirm that most colostomy hernias seem to develop in the first few years.136

of the rectum during the period 1968 through 1972 at St. Mark’s Hospital.149 Of the 227 patients who formed the basis of this study, three died in the postoperative period. By far, the most common stomal problem encountered was hernia, which occurred in 23 patients, approximately 10%. It was felt that the cumulative risk of developing a paracolostomy hernia in the sixth postoperative year was approximately 33%. The authors believed that extraperitoneal colostomy seemed to offer some protection against herniation. The other reported complications included retraction, stenosis, abscess, and prolapse. The cumulative incidence of all these stomal complications was approximately 7%. This report and others confirm that most colostomy hernias seem to develop in the first few years.136

Quality of life is an important area for assessment following colostomy, but there are few publications on this subject. Baxter and coworkers have developed a Stoma Quality of Life Scale to better analyze the results of this procedure.18 They were able to demonstrate that this instrument correlated well in those with improved versus those with worsened quality of life.

Alternative Techniques for Sigmoid Colostomy Creation and Management

Maturation by Stapling

In addition to the conventional maturation technique for creating a sigmoid colostomy, the circular stapling device has been advocated for performing end colostomies.45,134,195 This permits a geometrically perfect opening that can be theoretically calibrated to be optimal size for a particular bowel diameter.

Technique

Instead of a disk of skin being excised from the abdominal wall, a small opening is created just large enough to pass the center rod without the anvil. A purse string is created of the distal colon in the usual manner and the anvil inserted into the bowel. The cartridge and anvil are approximated, and the instrument is fired. One tissue “doughnut” consists of the skin, and the other is made up of the bowel. In effect, it is a colocutaneous anastomosis by means of the circular stapling device.

Another application of a stapler is the use of ordinary skin staples for maturing the stoma.11 They are then removed on the 10th postoperative day.

Opinion

Although the former procedure does have some theoretical appeal, it would certainly make the subcutaneous dissection and rectus splitting much more tedious. Furthermore, it is more likely that the inferior epigastric vessels will be injured during the course of the dissection. Moreover, as previously discussed, the factors that predispose to the subsequent development of stoma complications are related to ischemia, tension, improper location, and size of the abdominal wall opening—issues that are not avoided merely by creating a perfectly circular skin aperture.

As for the use of skin staplers to mature the stoma, one may reasonably ask what the advantage is when an additional effort must be made to remove them.

Continent Colostomy

The search for continence in a colostomy has stimulated many attempts to control bowel movements by means of prosthetic devices. Tenney and colleagues reviewed the various approaches that have been attempted or proposed.238 The authors considered the concepts according to four categories: external devices, surgical technique alone, surgical technique with passive implanted devices, and surgical technique with active implanted devices. There has been and continues to be considerable interest in developing a device for controlling bowel movements, whether for anal incontinence (see Chapter 16) or for ostomates. Initial publications are uniformly enthusiastic, but sometimes for inapparent reasons the product disappears from the literature and from the manufacturer’s inventory.

Kock Continent Colostomy

Kock and associates proposed a method, analogous to that of the continent ileostomy, through the use of the descending colon to create a nipple valve.130 In five patients, the end sigmoidostomy was provided with such a valve, but evacuation by irrigation through a catheter was laborious, and the procedure has since been abandoned.131 Some success was noted, however, with a continent cecostomy (see later).

Inflatable Cuff

A simple inflatable cuff has been attempted by the Mayo Clinic group, using the cuff end of a tracheostomy tube. The procedure was performed initially in animals and then in patients who had failed nipple valves following a Kock continent ileostomy. It was also considered for patients with conventional ileostomies who had not undergone a reservoir procedure. There appears to have been no further communication about this approach.

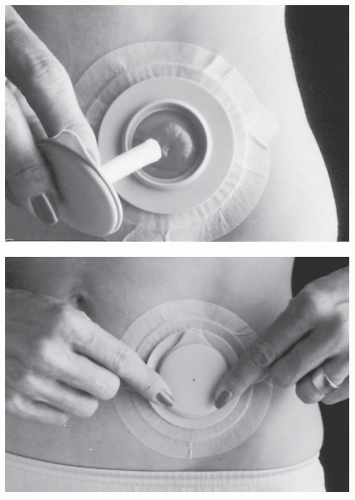

Colostomy Plug

In 1986, Burcharth and colleagues reported the use of a colostomy plug (Conseal; Coloplast, Inc., Tampa, FL) on 53 patients.35 The device is a two-piece system consisting of an adhesive baseplate and a disposable plug attachable to the plate (Figure 31-22). It is packed and compressed in a water-soluble film that disintegrates after insertion, allowing the plug to expand and prevent the passage of feces. Fecal continence and the passage of flatus without noise or odor were achieved in 90% of individuals.35 Patients were able to effectively use the device for a median application time of 8 hours. Potential advantages include the elimination of noise, the filtering of odor, the elimination of a pouch, and the lack of obtrusiveness.

Clague and Heald used this device in 100 individuals.47 Analysis of patient evaluations indicated that the plug restored continence and improved lifestyle in more than onethird of the ostomates who used it. Others have also reported a favorable experience with this device.48,224

Cerdán and colleagues describe a one-piece disposable plug composed of a soft, flexible cylinder of open-celled polyurethane foam.41 The device is supplied in a compressed form, enclosed in a water-soluble, lubricated, polyvinyl alcohol film. This is analogous to the plug illustrated in Figure 16-22 for the management of anal incontinence. The authors used the device in 20 patients with sigmoid colostomies. All but three found it comfortable and that it contributed to an improved quality of life. There were no complications associated with its use.

The use of a new continence device (Vitala) for colostomy patients was reported by Maxwell and colleagues.151 The appliance uses a pillow-shaped sealing element of

thin, plastic film (the Air Seal), which contains a soft foam that expands slowly, conforming to the shape of the stoma (Figure 31-23). A valve in the Air Seal allows it to inflate quickly and deflate slowly when external pressure is applied. Flatus can be released, and an in-built waste bag is deployed to capture any stool. In a preliminary study with 26 patients, the authors concluded that Vitala provides an important option for colostomy continence.151

thin, plastic film (the Air Seal), which contains a soft foam that expands slowly, conforming to the shape of the stoma (Figure 31-23). A valve in the Air Seal allows it to inflate quickly and deflate slowly when external pressure is applied. Flatus can be released, and an in-built waste bag is deployed to capture any stool. In a preliminary study with 26 patients, the authors concluded that Vitala provides an important option for colostomy continence.151

Artificial Sphincter

Szinicz described an implantable hydraulic sphincter prosthesis that consists of a compressible driving and control system together with a sleeve that is implanted around the bowel.234 The sleeve is connected to the compliance chamber by means of a connecting tube. The author reported his experience in animal experiments and in seven patients. Heiblum and Cordoba implanted an inflatable plastic balloon in the subcutaneous tissue around the stoma in order to achieve fecal continence.103 The connecting tube was tunneled subcutaneously from the balloon and brought out through a small wound at some distance from the stoma. The authors reported their experience in six patients, all but one of whom underwent the prosthesis insertion secondarily. Complete continence to feces and gas was obtained. One device had to be removed because it eroded the skin, and subcutaneous infection was a problem in three individuals. Here again, these approaches seem to have fallen off the surgical map.

Muscle Transplantation

Intestinal smooth muscle has been used to construct a continent colostomy.213 Freely transplanted, this is tailored as a 10- to 15-cm long segment of large intestinal muscle (usually the sigmoid), devoid of mucosa and mesenteric fat. The seromuscular sleeve is incised longitudinally through one of the taeniae, soaked in an antibiotic solution, and sutured to the serosa of the bowel approximately 2 or 3 cm proximal to the site for the creation of the stoma. Sutures are placed so that the transplant is imbricated. This creates a length of about 6 cm, which in effect increases the muscular mass. The author emphasizes that, after securing one edge of the graft, the muscle must be stretched maximally, and the graft wrapped around the bowel and secured. The mesenteric vessels are incorporated by the graft.

Schmidt reported his experience with this technique in more than 500 patients, 231 of whom underwent surgery in his own unit.213 Approximately 80% did not require an appliance, there was no mortality, and only five required removal of the surgical implant. Apparently, the transplants are nourished by means of secondary vascularization, and an irrigation technique facilitates defecation. In most patients who underwent the procedure secondarily, “nearly all viewed their postoperative situation as markedly improved.”

Kostov and coworkers used a modified smooth muscle “sphincteroplasty” for increasing intraluminal pressure in the colon proximal to the stoma in 72 rectal cancer patients.132 Their technique involves resection and transplantation of a 4-cm long portion of sigmoid colon muscularis. This is then passed around the colon through a defect in the mesentery, fixing it to the taenia. The procedure is combined with colonic irrigation to produce some level of bowel control and regularity. In an experience involving 72 patients, the weekly spontaneous stools were felt to be three to five times less frequent than in controls.

It seems that these publications have accrued a remarkably large number of patients, but unfortunately the surgeons as individuals or as groups who are interested in this problem seem to represent essentially that of lone experience.

Magnetic Colostomy

In 1975, Feustel and Hennig of Erlangen, Germany, described a device to create continence in patients who underwent conventional sigmoid colostomy: a magnetic ring implant.68

A ring of samarium cobalt encased in plastic is buried in the subcutaneous tissue around the colon. The colostomy is matured in the usual manner and, when the wound has completely healed (usually several weeks later), an external cap containing a ring magnet in the top and a core magnet in the center pin is inserted to create a plug.

A ring of samarium cobalt encased in plastic is buried in the subcutaneous tissue around the colon. The colostomy is matured in the usual manner and, when the wound has completely healed (usually several weeks later), an external cap containing a ring magnet in the top and a core magnet in the center pin is inserted to create a plug.

Results of the magnetic continent colostomy device were initially quite favorable, although subsequent results have been less optimistic.91 Khubchandani and associates reported their experience in 14 patients, one-half of whom had good results.129 There was no morbidity attributable to insertion of the ring, and there was no incident of wound infection. However, other problems developed, including the triggering of security monitors at airports, disturbances of television reception if one is sitting close, malfunctioning of wrist watches, and adherence of the patient to anything metallic (e.g., a kitchen sink). Alexander-Williams and associates reviewed their experience with 61 patients: 55 primary and 6 secondary implants.7 One individual died, possibly as a consequence of sepsis at the site of the implant. Twelve (20%) required removal of the ring because of failure of healing or late skin necrosis. Approximately one-half of the remaining patients were not using the magnetic cap at all at the time of the review. The reason for this failure was the fact that the device did not afford complete continence. Of the 21 patients who used the cap regularly, 15 were continent. In these authors’ experience, therefore, only one-fourth of the patients who underwent the operation were completely continent.

Kewenter reported 21 patients who underwent magnetic colostomy, all but three of whom had the procedure performed at the time of the primary resection.127 Three died soon after operation (unrelated to the surgery). Eight were considered a success in that the cap was used under all circumstances, and two patients were considered partial successes. If one groups these two categories together, excluding the patients who expired, the rate of success with the procedure in Kewenter’s experience was 44%.

Comment

It appears that implantation of the magnetic stoma device is not a very forgiving technique. It requires meticulous dissection and careful patient selection. Complete control is successful in no more than 50% of patients. The matter now, however, is academic because the device has been taken from the market and is no longer available. As a consequence, I no longer include a description of the operative technique or the illustrations in this text, but I do wish to recommend to the reader and to the future investigator that the concept of an implanted device for creating a continent colostomy should not be resurrected. The following is another.

Implantable Ring and Balloon Plug

In 1983, Prager described a device for control of feces following abdominoperineal resection and sigmoid colostomy.188 It is composed of two parts: a silicone ring, which is produced in three different internal diameters with a flange on the upper surface reinforced with Dacron mesh, and a silicone balloon, which is made in varying lengths. The balloon is inflated and deflated by means of a 30-mL syringe. The ring is implanted within the peritoneal cavity and sewn onto the undersurface of the abdominal wall where the opening has been made for the stoma to be delivered. The abdominal incision is then closed, and the colostomy matured in the usual manner. Beginning approximately 1 week after the operation, the patient begins to use the plug.

Results

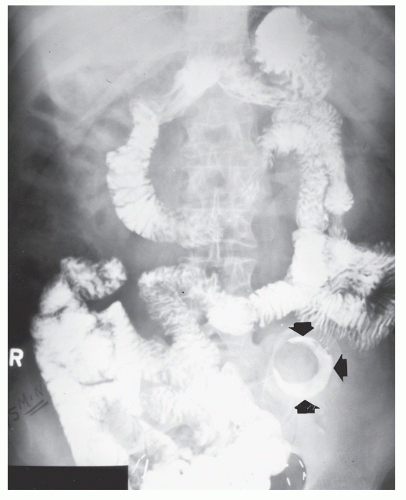

A multicenter study was undertaken to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the device.189 Seventy-four patients underwent insertion of the ring.189 Three were removed because of encapsulation of the ring. This is a complication common to all medical-grade implantable silicon and appears to be an insoluble dilemma. Two patients had the rings removed because of bowel necrosis or fistulization (Figure 31-24). Many individuals elected not to use the plug, preferring instead to employ a conventional appliance or irrigation.

Comment

As with the magnetic ring colostomy device, the implantable ring and balloon plug are no longer available because of the complications of erosion and necrosis of the stoma or bowel.

Colostomy Irrigation

Colostomy irrigation is a method of bowel control offered to selected patients with sigmoid or descending colon colostomies (see also the following chapter). Success depends on personal interest, bowel habits before surgery, manual dexterity, available toilet facilities, and lifestyle. Gawron suggests the following selection criteria for colostomy irrigation81:

Permanent descending or sigmoid colostomy

Physically and mentally capable of performing self-care

Motivated to learn the procedure and adhere to a schedule

No prior history of IBD, radiation therapy (to the abdomen or pelvis), or other major intestinal resection

A history of regular bowel pattern or constipation

Availability of bathroom facilities, including running water

Irrigation techniques are often taught on the fifth or sixth postoperative day, and for some individuals, a few months following the operation. Again, because of cost-containment and the possibility of delaying discharge, some patients may require instruction a few weeks later.

Most individuals tend to return to the bowel habits they had prior to operation, usually within 6 to 12 weeks after surgery. In other words, if one defecated every morning after breakfast, the colostomy will probably function on that schedule. Under these circumstances, irrigating may be unnecessary, and such patients can frequently avoid an appliance for the rest of the day or merely use a small dressing. A closed-ended “security pouch” can also be employed.

Conversely, if a patient had irregular bowel function preoperatively, the colostomy will probably act irregularly postoperatively. Such a person may be more content by irrigating. However, under no circumstances should one insist that the stoma be irrigated. It may be advisable to learn the technique, but the decision whether to actually use irrigation should be personal.

Method

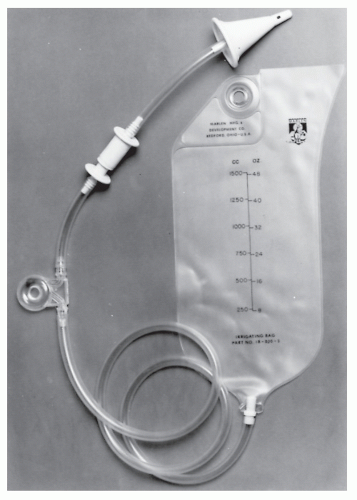

A nipple, cone, or catheter is inserted into the stoma. The cone tip is now being used more frequently for colostomy irrigation than the catheter, not only because there is less risk of perforating the bowel but also because it provides a dam to prevent backflow. If a catheter is selected, it should be inserted no farther than 3 in. A rubber nipple with a hole enlarged to accommodate the catheter tip can act as a flange and temporary dam while fluid is running in. Several companies manufacture irrigation kits (Figure 31-25).

The colon does not need to be washed out; the bowel is merely stimulated with the irrigant to produce evacuation. The bottom of the bag for irrigation is usually placed at shoulder height when the patient is seated. However, the height of the bag should be adjusted to permit a steady flow into the stoma.71 An alternative technique has been suggested by Schwemmle and coworkers; a specially constructed basin is used at stoma level when the patient is standing.215 Obviously, this requires a unique plumbing arrangement in the patient’s bathroom.

Tepid water (750 to 1,000 mL) is slowly instilled over a 5- to 10-minute period. After waiting approximately 1 minute, the patient removes the cone, and the water and stool are permitted to pass through the irrigation sleeve into the toilet bowl. Most of the returns are usually collected within 15 minutes. The collecting sleeve can then be closed while one tends to other activities. After about 45 minutes, the irrigant usually will have been expelled. With time, the patient may require irrigations only every 48 hours or even every 72 hours. Some, however, may never be able to irrigate satisfactorily and may require a pouch all of the time. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to justify the time and effort expended to perform this task.

Results

Meyerhoff and colleagues performed a randomized study, comparing the effects of irrigating with different volumes: 250, 500, and 1,000 mL.159 A double-isotope technique was developed to evaluate colonic emptying of irrigation fluid and feces. This was accomplished through radioactive labeling of the fecal contents by the ingestion of 10 MBq69Cr-EDTA 24 hours before scintigraphic investigation. The authors discovered that the general recommendation of 1,000 mL is not optimal for all patients. In many instances, a volume of 500 mL was preferred because of reduced inflow time, complete colonic emptying of more consistent fecal contents, and minimal retention of irrigant. It appears, therefore, that one should experiment with different irrigation volumes in order to determine the most efficacious program for the individual.

FIGURE 31-25. Colostomy irrigating system. This unit has a soft-tipped cone. (Courtesy of Marlen Manufacturing and Development Co., Bedford, OH.) |

Watt categorized those patients who probably are not candidates for controlling bowel elimination by irrigation as follows: those with irritable bowel syndrome, individuals who underwent irradiation therapy and sustained radiation enteritis, and the terminally ill. Stomal management problems such as hernia and stenosis, poor eyesight, impaired dexterity, fear of the irrigation procedure, and resentment of the time necessary militate against irrigating.260

Terranova and colleagues evaluated irrigation and compared the technique with natural evacuation in 340 patients.239 They concluded that because of the feeling of security gained by relative continence, cleanliness, and the avoidance of an appliance, the vast majority of patients preferred irrigating. Williams and Johnston performed a prospective randomized study using colostomy irrigation and natural evacuation in 30 selected patients.266

The mean time spent managing the stoma was 45 minutes per day in the spontaneous group versus 53 minutes when irrigation was performed. Because of reduction of odor and flatus, the lack of requirement for medication, and the ability of many to avoid an appliance, irrigation seemed to offer an improved lifestyle. In a questionnaire response of 223 patients from the Mayo Clinic, 60% were “continent” with irrigation, 22% were “incontinent” with irrigation, and 18% had discontinued the technique for various reasons.119 Doran and Hardcastle performed a controlled trial of colostomy management by natural evacuation, by irrigation, and by means of a foam enema.61 By evaluating 20 patients who used each technique for 2 months, the authors concluded that almost all felt that irrigation or the foam enema improved their quality of life. Furthermore, they opted to continue with irrigation on completion of the study.

The mean time spent managing the stoma was 45 minutes per day in the spontaneous group versus 53 minutes when irrigation was performed. Because of reduction of odor and flatus, the lack of requirement for medication, and the ability of many to avoid an appliance, irrigation seemed to offer an improved lifestyle. In a questionnaire response of 223 patients from the Mayo Clinic, 60% were “continent” with irrigation, 22% were “incontinent” with irrigation, and 18% had discontinued the technique for various reasons.119 Doran and Hardcastle performed a controlled trial of colostomy management by natural evacuation, by irrigation, and by means of a foam enema.61 By evaluating 20 patients who used each technique for 2 months, the authors concluded that almost all felt that irrigation or the foam enema improved their quality of life. Furthermore, they opted to continue with irrigation on completion of the study.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree