Michael O. Koch, MD

Conventional treatments for localized prostate cancer have been consistently associated with untoward effects on patients’ quality of life, primarily urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction. Although quality of life outcomes have been shown to be minimized when treatment is performed by high-volume surgeons, even the most capable surgeons have significant rates of impotence and urinary incontinence (Begg et al, 2002). The significance of these side effects of therapy is further amplified by the frequently indolent nature of this disease, which may take more than a decade to progress. Thus while the severity of these side effects of therapy may pale in comparison with other cancer surgeries, their overall impact after adjusting for the remaining years of life affected is quite large. Thus there remains a need for therapies that reduce the side effects of prostate cancer therapy while maintaining efficacy.

High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound Technology

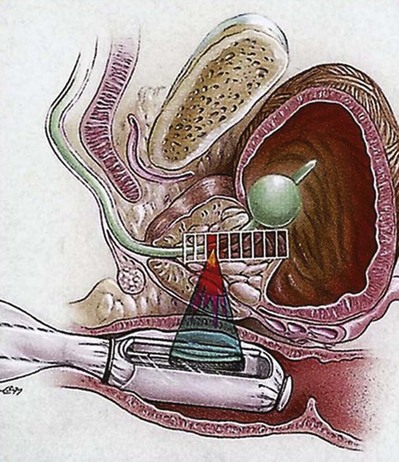

HIFU uses high-energy ultrasound waves to destroy the tissue at the focal point of a transducer without injuring the intervening tissue. Strong ultrasound waves in the inaudible sound range and approximately 10,000 times stronger than diagnostic ultrasound are generated by a transducer with a parabolic configuration (Fig. 106–1). This parabolic configuration focuses these sound waves into a discrete focal point measuring approximately 3 mm × 3 mm × 11 mm. This focal point is located 3 to 4 cm distant from the transducer, and its size and shape is dependent on the energy emitted by the transducer, the geometric configuration of the transducer, and the characteristics of the tissue. At the focal point of the transducer, ultrasound energy is concentrated, is absorbed by the tissue, and generates temperatures that can exceed 80° C, resulting in coagulative necrosis and the destruction of tissue.

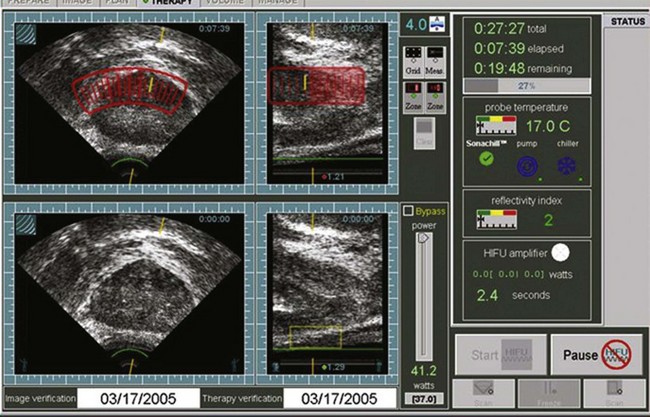

The procedure is performed by imaging the prostate in the coronal and sagittal planes with a transrectally placed stationary probe. This probe allows both imaging and treatment of the prostate. The treating physician outlines the areas to be treated in both planes (Fig. 106–2). This focal point is then sequentially moved through the tissue to be destroyed by a computer-driven system that moves the parabolic transducer sagittally and coronally until the entire selected area has been coagulated. Treatment of contiguous areas of the prostate consecutively would result in heat build-up within that area of the prostate and the conductive spread of heat and thermal injury of the tissue. Conductive spread of the heat energy would negate the anatomic precision of the treatment, and the primary advantage of HIFU technology is the precise nature of the coagulated treated foci. In order to prevent the conductive spread of thermal energy through the prostate, the computer-controlled transducer is moved throughout the treatment to noncontiguous areas to allow treated areas to cool down. Eventually, all areas are treated as the transducer moves back and forth. Because of the lack of adjacent tissue damage, HIFU is a repeatable precise technology.

General Clinical Use of High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound

This technique was initially investigated in both animals and humans in the 1940s and 1950s to destroy selective regions in the central nervous system (Fry et al, 1954; Fry and Johnson, 1978). It is now recognized that HIFU has the capability of transdermally or transmucosally coagulating and destroying tissue in a variety of conditions that have medical applications including spleen, liver, kidney, breast, uterus, and bone (Vaezy et al, 1997, 1999; Wu et al, 2001).

HIFU has been most well studied in the treatment of prostatic conditions. HIFU was initially tested in experiments in the canine prostate by Gelet and colleagues (1993), Bihrle and colleagues (1994a), and Kincaide and colleagues (1996). The use of the transrectal probe for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) in humans was first reported in the mid-1980s at Indiana University and by Madersbacher and colleagues in Vienna (Bihrle et al, 1994a; Madersbacher et al, 1994). HIFU was used to coagulate the periurethral area of the prostate in these series. The most common complication from the HIFU treatment was transient urinary retention, which occurred in 73% of patients. Two subsequent and larger studies have examined the efficacy and safety of the use of HIFU for the treatment of symptomatic BPH (Nakamura et al, 1997; Madersbacher et al, 2000). HIFU has not been widely used for the treatment of symptomatic BPH because of its relatively invasive nature in comparison to other thermal-based modalities such as microwave and radiofrequency ablation. Currently, HIFU does not have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of BPH in the United States. HIFU currently has FDA approval for the treatment of uterine fibroids in the United States.

High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound In Localized Prostate Cancer

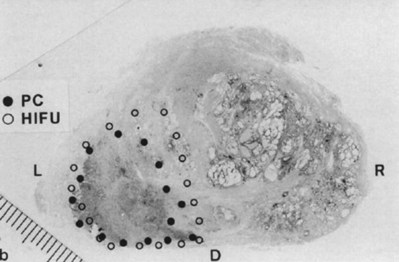

Madersbacher and colleagues (1995) were the first to examine the feasibility of HIFU for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. These investigators treated 29 patients with HIFU therapy immediately before radical prostatectomy using a predecessor of the currently used Sonoblate-500 device. They demonstrated that HIFU resulted in a sharply demarcated lesion with no treatment effects in areas immediately adjacent to the treatment zone. Two of these patients had sharply demarcated cancerous lesions on ultrasound and had this area targeted with HIFU (i.e., partial prostatic treatment). In these patients, no heat damage was noted to the rectum or neurovascular bundle even though HIFU was extended to the prostatic capsule (Fig. 106–3). Beerlage and colleagues (1999) subsequently confirmed these findings using the EDAP device.

(From Madersbacher S, Pedevilla M, Vingers L, et al. Effect of high-intensity focused ultrasound on human prostate cancer in vivo. Cancer Res 1995;55:3346–51.)

Gelet and colleagues (1996, 2000) reported on the use of the Ablatherm device in 82 patients with stage T1-2 prostate cancer and subsequently presented comprehensive outcome data in 2000 (Table 106–1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree