Fig. 10.1

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): dilated intrahepatic bile ducts with multiple stones over stricture of hepaticojejunostomy (secondary intrahepatic lithiasis)

10.2 Etiology

The etiology of primary hepatolithiasis remains not fully understood, but genetic, dietary, and environmental factors are thought contributing factors.

In Western countries PIL is strictly related to congenital bile duct dilatation with intrahepatic-only localization corresponding to Todani type V [4]. This entity was first described by Caroli et al. [5] in 1958 and later classified by Guntz et al. [6] according to the morphology and the extent of intrahepatic bile duct dilatations. A recent multicenter study conducted by the French Association of Surgery [7] has shown that prevalence of intrahepatic lithiasis in patients with Caroli’s disease is above 50 %, whereas in Eastern patients, it seems mainly related to biliary infestations and infections [8].

Typically there are two types of intrahepatic stones : calcium bilirubinate stones (brown pigment stones) and cholesterol stones. Calcium bilirubinate stones, mainly composed of bilirubin, cholesterol, fatty acids, and calcium, represent the majority of intrahepatic stones, whereas cholesterol stones comprise 5.8–13.1 % of all intrahepatic stones [2]. Pathogenesis of intrahepatic stones involves not only the precipitation of calcium bilirubinate, but also an altered cholesterol metabolism.

In addition bile duct stricture , either congenital or acquired, and infection with β-glucuronidase-producing bacteria play a key role in bilirubin precipitation and formation of calcium bilirubinate stones, which are mostly observed in Eastern countries [1, 2, 9]. Lower socioeconomic status and poor hygiene may be involved in the development of intrahepatic stones [10].

Recently, Shoda et al. [11] has shown that pathogenesis of intrahepatic cholesterol stones formation is based upon the dual defects of upregulation of cholesterol synthesis and downregulation of bile-acid synthesis in the liver, possibly in association with defective secretion of phospholipid by its canalicular transporter, multidrug resistance protein (MDR3). Metabolic factors, either acquired or congenital, act synergistically in the development of these intrahepatic stones [1, 12].

Some investigators have reported that anatomic variations of intrahepatic bile ducts can cause hepatolithiasis. Notably, hepatolithiasis is more frequent in the left than in the right lobe, and the acute angle which the left hepatic duct forms at the junction with the common bile duct (CBD), which tends to induce bile stasis when associated with biliary strictures, has been advocated as a key point for this higher rate [1] (Fig. 10.2). In the right lobe the duct of segment 6 alone or of the posterior sector seems the most frequently involved, and also in this case the anatomy of the junction of the ducts of these segment or sector could play a major role (Fig. 10.3). Furthermore, it was reported [13] that confluence of the right posterior bile duct into the left hepatic duct (Norman’s anomaly [14]) may also play a role in the development of PIL. However, in a recent comparative study between patients with PIL in Taiwan and Japan, anatomic variations of intrahepatic segmental bile ducts did not seem to play any important role in the pathogenesis of PIL [15]. Therefore, the role of anatomic variations of intrahepatic bile ducts in hepatolithiasis remains unclear, although in clinical practice in Western countries anatomic variations of intrahepatic bile ducts are frequently observed in patients with intrahepatic lithiasis (Fig. 10.4).

Fig. 10.2

(a) Abdominal MRI: intrahepatic lithiasis of the left hemiliver. (b) Surgical specimen after left hepatectomy: dilated bile ducts with multiple stones

Fig. 10.3

(a, b) Abdominal MRI, (c) MR cholangiography: dilated bile ducts of right posterior sector with stones and parenchymal atrophy of the sector (arrows)

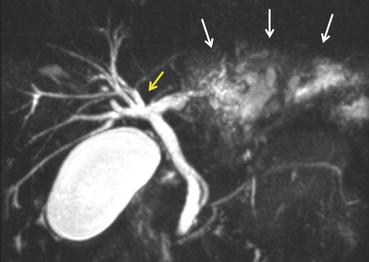

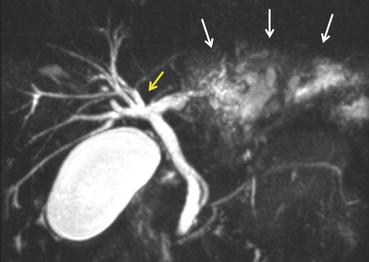

Fig. 10.4

MR cholangiography: dilated left lateral sectorial bile ducts with stones (white arrows); anomalous biliary main confluence (yellow arrow)

10.3 Clinical Presentation

Abdominal pain , either in the right upper quadrant or in the upper abdomen, generally is the most frequent initial symptom. Symptoms of hepatolithiasis include cholangitis , jaundice, and acute pancreatitis. Other abdominal complaints, including abdominal discomfort and vomiting, may be observed. In asymptomatic patients hepatolithiasis may be an incidental finding on abdominal imaging; this occurs with increasing frequency due to the advances in diagnostic imaging modalities and the popularization of routine medical examination.

Most patients have a long history of previous biliary operative and nonoperative treatments and tend to have consequent recurrent pyogenic cholangitis as the most common clinical sign. Pyogenic cholangitis may cause further septic complications such as hepatic abscess and may ultimately result in limited parenchymal atrophy or secondary sclerosing cholangitis. Indeed, the most frequently observed clinical history of patients with PIL includes several endoscopic treatments by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) for recurrent stones of CBD. Patients usually first undergo cholecystectomy and then present with recurrent CBD stones misdiagnosed as residual stones that migrated from the gallbladder. For this reason they usually undergo several endoscopic treatments of the CBD stones, frequently without any further complete investigation of all the intrahepatic biliary tree. Patients usually develop recurrent cholangitis which can evolve into intrahepatic abscesses. It is important to consider that after multiple endoscopic or percutaneous treatments and recurrent episodes of cholangitis and medical treatments, it is likely to find multiresistant bacteria into the bile ducts, which strongly influence subsequent clinical history of these patients and the results of treatment. This fact should be strongly emphasized and microbiological cultures of bile should be performed whenever possible from external biliary drainages (percutaneous biliary drainage, naso-biliary drainage).

The Hepatolithiasis Research Group in Japan has proposed a clinical grade classification to quantify the severity of hepatolithiasis [16]: Grade 1, absence of symptoms; Grade 2, abdominal pain; Grade 3, transient jaundice or cholangitis; and Grade 4, persistent jaundice, sepsis, or cholangiocarcinoma.

10.4 Evolution

Late complications of hepatolithiasis include liver abscesses, pyogenic sepsis, parenchymal atrophy, persistent liver dysfunction resulting in secondary biliary cirrhosis, and cholangiocarcinoma . The latter two represent, therefore, the major risks in patients with intrahepatic lithiasis. It is presumed that chronic inflammation of the bile ducts by bile stasis, stones, and infestation with parasites can lead to adenomatous hyperplasia of the epithelium and subsequently to cholangiocarcinoma.

Hepatolithiasis is an established risk factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) in Asian countries, with 2–10 % of patients with hepatolithiasis developing ICC [17]. The Korean, hospital-based, case–control study by Lee et al. found a strong association between hepatolithiasis and ICC, with an OR of 50.0 (95 % CI = 21.2–117.3) [18]. A Chinese, hospital-based, case–control study by Zhou et al. also showed a significant association, with the OR at 5.8 (95 % CI = 1.97–16.9) [19]. There are less data on the relationship between hepatolithiasis and ICC in Western countries, but a recent Italian multicenter study showed that prevalence of ICC in patients who underwent liver resection for intrahepatic lithiasis was 14.3 % [20].

Previous reports showed that bilirubin stones [21], irregular ductal stricture or obstruction, age over 40 years, a long history of hepatolithiasis with weight loss, high level of serum alkaline phosphatase, low level of serum albumin, high level of the serum carcinoembryonic antigen, and/or hepatolithiasis in the right or both lobes [22] were predictive factors for cholangiocarcinoma associated with hepatolithiasis. In a recent Japanese multicenter study, the authors showed that previous choledocoenterostomy and liver atrophy may increase the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma [23].

Despite the high number of suspected risk factors, preoperative diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in these patients is usually difficult because hepatolithiasis and related periductal inflammation hinder clear visualization of bile ducts by imaging techniques; therefore, especially in patients with biliary strictures in whom is very difficult to rule out a malignant stricture with certainty, liver resection should always be considered, and the possibility to find a cholangiocarcinoma should always be kept in mind. Indeed the multicenter Italian study [20] showed that a preoperative suspected diagnosis of ICC was obtained in only 39.1 % of the patients initially evaluated for resection for intrahepatic lithiasis; in the other cases diagnosis of ICC was performed intraoperatively and postoperatively in 26.1 and 34.8 %, respectively. Therefore, the risk of the presence of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with longstanding PIL and of development of cholangiocarcinoma in young patients with PIL, or in patients treated for a long period of time by nonsurgical treatments (Fig. 10.5), should always be considered when choosing the treatment. In case of postoperative diagnosis at pathology of unsuspected cholangiocarcinoma, reoperation to perform more radical procedure (more extended parenchymal resection, resection of main biliary confluence, lymphadenectomy) if necessary should be also considered [24]. Furthermore, development of cholangiocarcinoma has been reported also in patients with previous liver resection for hepatolithiasis; therefore, patients resected for PIL should be carefully followed up for early detection of cholangiocarcinoma [25].

Fig. 10.5

Forty-eight-year-old male patient. Fifteen years previously (33 years old) diagnosis of intrahepatic lithiasis of the right posterior sector (a, Abdominal MRI), treated percutaneously: (b) PTC, bile ducts of right posterior sector completely filled by stones; (c) balloon dilatation of biliary stricture; and (d) final cholangiography; clearance of the majority of the stones; residual intrahepatic bile ducts dilation. Five years later cholangitis, with recurrence of intrahepatic lithiasis: (e) PTC, stones recurrence (short arrow) above sectoral biliary stricture (thin arrow); (f) percutaneous treatment, double balloon dilatation of biliary stricture; (g) final cholangiography after complete removal of lithiasis, residual intrahepatic bile strictures (arrows). Nine years later increase of alkaline phosphatases and gamma glutamyl peptidases. (h, i) Abdominal MRI: atrophy of right posterior sector and hypotrophy of the remnant right hemiliver, with appearance of a dishomogeneous mass in the right posterior sector without portal flow in the relative portal branch. Referral at our unit and indication to surgery. (j ) Intraoperative field after right hepatectomy, excision of main biliary confluence and CBD, left hepaticojejunostomy, and lymphadenectomy. (k) Surgical specimen: intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma invading the right posterior portal branch

10.5 Therapy

Treatment of PIL still remains particularly difficult and controversial. Several surgical, endoscopic, and percutaneous procedures have been reported in the literature, but high recurrence rates are often reported.

10.5.1 Surgical Treatment

Liver resection represents the only treatment which can allow the complete removal of intrahepatic stones together with affected bile ducts. The most frequent indications for liver resection reported in the literature are the following: lithiasis limited to one lobe, sector, or segment; parenchymal hypo-atrophy; liver abscess; failure of previous treatments; and suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Indication in asymptomatic patients is more controversial, but young age of patients, low surgical risk of resection, and risk of early and late complications of other treatments should require liver resection in localized forms of PIL (Fig. 10.6).

Fig. 10.6

Sixty-seven-year-old male patient, with right intrahepatic lithiasis, simple liver cysts, gallbladder stones; no symptoms. (a, b) MRI: dilated intrahepatic biliary tree (arrows) with stones (short arrows). (c, d) MR cholangiography: diffusely dilation of right intrahepatic bile ducts (arrows); CBD and left intrahepatic bile ducts (thin arrows) not dilated. (e) Surgical specimen after right hepatectomy: dilated bile ducts with multiple stones

Liver resections in patients with PIL have been frequently reported by Eastern centers for the high prevalence of the disease [26–29]. More rarely and with lower number of patients, liver resections are reported by Western centers [7, 30–37]. This is related mainly to the lower incidence of intrahepatic lithiasis in Western countries, but probably also to the relatively unawareness of this disease and of the possible severe late complications, to the wide availability of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments, and to the concern for the operative risk of hepatectomy.

Perioperative mortality of resection of the majority of recent series from all the Western centers was nil [31–37]. Also in Eastern series postoperative mortality was low, ranging from 0 to 3.5 % [26–29, 38] in spite of higher complexity of disease than that reported in Western series (higher rate of bilateral intrahepatic lithiasis and cirrhosis).

Postoperative morbidity rates in Eastern and Western series ranged from 7.4 to 58.8 % [26–38] which mainly include septic complications due to preoperative recurrent cholangitis, frequently related to previous endoscopic or percutaneous treatments. In our experience on 75 patients resected between 1992 and 2012 for PIL, mortality was nil and morbidity rate was 40 % (30 pts); 83 % of complicated patients (29 cases) had septic complications: all these patients had persistent postoperative fever, in 5 cases with subdiaphragmatic abscess and in 12 cases with bile leak. In 79 % of these patients, positive bile cultures were found preoperatively, and the same bacteria were detected from surgical drainages after resection, with positive blood culture in 48 % of these patients. Multivariate analysis identified previous endoscopic or percutaneous treatments and preoperative cholangitis as the only two independent risk factors for septic complications.

Early diagnosis of the disease and surgical treatment at an early stage are key factors for performing liver resections with low operative risk [39]. Noninvasive diagnostic approach by CT and MR for accurate evaluation of the disease and strict avoidance of endoscopic or percutaneous diagnostic approach with consequent biliary infection may prevent postoperative severe septic complications which can explain the high mortality rate of surgery (7.4 %) reported by Kassahun [30]. Actually, effective control of sepsis should be always strongly pursued before liver resection. For patients with acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis with intrahepatic stones, emergency percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage is indicated and should be preferred to endoscopic transpapillary approaches (Fig. 10.7). Furthermore, in these patients intraoperatively it is mandatory to take samples of bile from intrahepatic bile ducts for microbiological cultures , irrigate all the intrahepatic biliary tree with large amount of saline solution, and leave in place a biliary drainage at the end of resection (Fig. 10.8). In fact the most frequent and severe postoperative complications are sepsis related, and the possibility to get bile samples during the postoperative course is extremely useful. Among septic complications, patients with hepatolithiasis may develop thrombocytopenia and enhanced platelet activation, resulting in coagulation and fibrinolysis disorders, which could be particularly severe after liver resection [40].

Fig. 10.7

Fifty-six-year-old female with acute cholangitis, already submitted to choledochoduodenostomy for lithiasis. (a) Abdominal MRI, dilated left hepatic duct (short arrows) above stone (yellow arrow); (b) PTC: percutaneous treatment of cholangitis; insertion of biliary drainage; stone in the left hepatic duct (arrow); subsequent liver resection

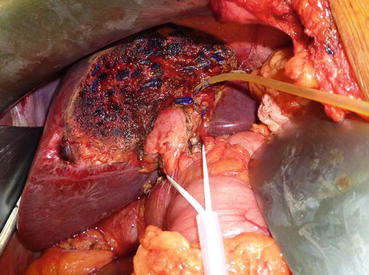

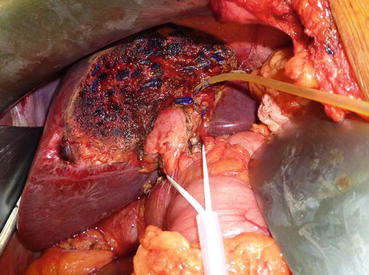

Fig. 10.8

Intraoperative field after left hepatectomy with placement of biliary T-tube in the stump of the left hepatic duct

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree