EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HEPATITIS B VIRUS, HEPATITIS C VIRUS, AND HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTIONS IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

National surveillance of dialysis-associated diseases in the United States in 2002 demonstrated the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-HCV antibody, and HIV infection at 1.0%, 7.8%, and 1.5%, respectively (9). In 2002, a minority of hemodialysis centers were routinely screening for HIV, so the 1.5% HIV prevalence in dialysis centers may be an underestimate. These data are the result of surveillance questionnaires administered by the CDC to all chronic hemodialysis centers licensed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The 4,035 centers representing 263,820 patients and 58,043 staff were surveyed regarding hemodialysis practices, disposable dialyzer reuse, cleaning and disinfection procedures for dialysis equipment, HIV prevalence, HBV vaccination coverage, and the results of testing patients for HBsAg and anti-HCV antibody (10). The study found that the incidence of viral hepatitis did not differ substantially according to infection control practices.

In 2002, 27.3% of U.S. centers reported at least one patient with chronic HBV and 2.8% of centers reported at least one newly acquired HBV infection. Patients still acquire HBV infection in hemodialysis centers due to inadequate infection control or breaches of technique (9). The risk of seroconversion for patients with untreated percutaneous exposure to HBV is as high as 30% (11). In 2002, HBV incidence was 0.12% overall but higher in centers where injectable medications were prepared on medication carts in treatment areas compared to centers with a separate medication room. According to a cross-sectional study of 8,615 adult hemodialysis patients in Western Europe and the United States, the prevalence of HBV infection in this population ranges between 0% and 7% (4,12). In developing countries, rates of chronic HBsAg carriers range from 2% to 20% (4). Higher rates in developing countries are attributed to the higher background prevalence of HBV and difficulties following infection control strategies against HBV in the setting of lack of infrastructure and financial resources (4).

Although HCV seroprevalence among U.S. dialysis patients is 5 times higher than in the general population (7.8% vs. 1.6%), HCV incidence has been declining (13). In 2002, HCV incidence at U.S. dialysis centers was 0.34%, representing a significant decline from the previous decade (6). Centers using disposable containers for priming dialyzers demonstrated significantly lower HCV incidence (9). HCV transmission may occur in centers having opportunities for cross-contamination among dialysis patients, including failure to disinfect contaminated equipment or shared environmental surfaces. The duration of time on dialysis is the most important risk factor independently associated with HCV infection (6). Employment of nurses with at least 2 years of formal dialysis training is associated with lower seroconversion risk (14).

The proportion of U.S. hemodialysis patients with HIV increased from 0.3% to 1.4% from 1985 to 1999 (6); more recent estimates show stability with about 1.5% since 2002 (9). Patient-to-patient transmission of HIV infection has not been reported in American hemodialysis centers. In other countries, however, HIV transmission has been attributed to mixing of reused access needles and inadequate equipment disinfection procedures (15).

MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS, HEPATITIS C VIRUS, AND HEPATITIS B VIRUS INFECTION IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS, HEPATITIS C VIRUS, AND HEPATITIS B VIRUS INFECTION IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

With the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), survival of HIV-infected patients on hemodialysis has vastly improved. A 2-year prospective French study followed all HIV-infected patients on hemodialysis in France through 2003. Survival was compared with that of 584 hemodialysis patients who did not have HIV infection in the same period. The 2-year survival rate was statistically indistinguishable from the survival of the control cohort. However, there were some significant mortality risk factors including low CD4+ T cell count (hazard ratio [HR] 1.4/100 CD4+ T cells per mm3 lower), high viral load (HR 2.5/1 log10 per mL), absence of HAART (HR 2.7), and a history of opportunistic infection (HR 3.7) (16). Nevertheless, HIV-infected patients who are taking appropriate HAART and getting proper follow-up are comparable to non–HIV-infected end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients with regard to morbidity and mortality.

Among maintenance hemodialysis patients, HCV is associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality across almost all clinical and demographic groups (17,18). A database of 13,664 dialysis patients who underwent HCV testing during a 3-year interval (through June 2004) was analyzed. In logistic regression models, HCV infection was linked to younger age, male gender, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, Medicaid insurance, longer dialysis duration, unmarried status, HIV infection, and smoking. The mortality HR associated with HCV infection was 1.25 (95% confidence interval 1.12 to 1.39; p <0.001) (5). A longitudinal study showed a mortality rate of 33% for HCV-infected dialysis patients, compared with 23.2% mortality for the HCV-uninfected dialysis group over a 6-year follow-up (18).

In contrast to HCV, HBV-related liver disease in the hemodialysis population has a relatively benign course (19). Although HBV infection in hemodialysis patients more often results in a chronic carrier state compared to patients without kidney disease, the risk of death from liver disease is low (11,20). No significant difference in mortality between dialysis patients according to HBsAg status has been consistently shown (4,21,22). There are contradictory data from a small study in India, which indicates that HBsAg-positive hemodialysis patients had a higher mortality rate (72.7% vs. 21.4%) than HBsAg-negative hemodialysis patients due to fulminating hepatic failure in these individuals (4,23).

SCREENING AND PREVENTION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS, HEPATITIS B VIRUS, AND HEPATITIS C VIRUS IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

SCREENING AND PREVENTION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS, HEPATITIS B VIRUS, AND HEPATITIS C VIRUS IN HEMODIALYSIS PATIENTS

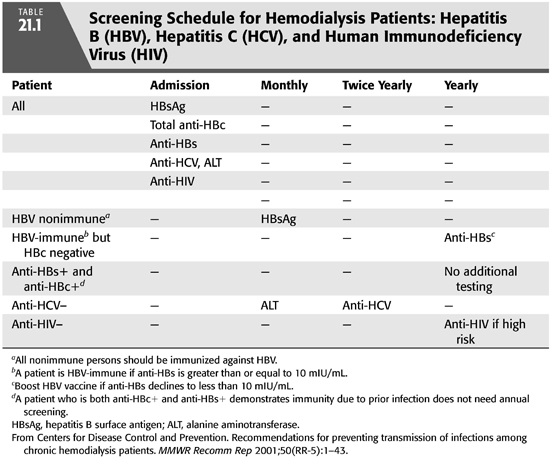

In 2006, the CDC issued revised guidelines for HIV screening in the general population as follows: “HIV screening is recommended for patients in all health-care settings after the patient is notified that testing will be performed unless the patient declines (opt-out screening). Persons at high risk for HIV infection should be screened for HIV at least annually (TABLE 21.1). Separate written consent for HIV testing should not be required; general consent for medical care should be considered sufficient to encompass consent for HIV testing” (24). These guidelines apply equally to the population receiving chronic hemodialysis. Therefore, all individuals should be screened before the initiation of hemodialysis (FIGURE 21.1) and annually thereafter if they are at high risk. The definition of individuals at high risk for HIV infection includes injection drug users, men who have sex with men and persons with multiple sexual partners including those who exchange drugs or money for sex, and heterosexual partners of HIV-infected persons. There is no recommendation to segregate HIV-positive from HIV-negative dialysis patients or to dedicate dialysis machines solely to HIV-positive patients. As of 2015, there is no effective vaccine for the prevention of HIV, and prevention of infection requires education of patients and staff to minimize risk (25).

Hepatitis B Virus Screening and Immunization

Hepatitis B screening is especially critical in hemodialysis units because HBV-infected patients need to be isolated in a separate room and assigned dialysis equipment, instruments, supplies, and staff members that are not shared by HBV-susceptible patients (6). Several tests for which serologic assays are commercially available may be used to diagnose HBV infection. These include HBsAg and anti-HBs, anti-HBc, hepatitis B envolope antigen (HBeAg), and antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe) (TABLE 21.2). One or more of these markers are detectable during phases of HBV infection (6).

HBsAg indicates ongoing HBV infection and the potential for transmission to others. Among newly infected patients (FIGURE 21.2), serum HBsAg is found 30 to 60 days after exposure to HBV and persists for variable periods. Anti-HBc antibody develops in all HBV infections, appearing at onset of liver enzyme elevations in acute infection and persisting for life. Acute infection can be detected by immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-HBc antibody, which persists for up to 6 months (6).

For those who recover from HBV (>85% of adults), HBsAg is eliminated from blood in 2 to 3 months, followed by the development of anti-HBs antibody. Anti-HBs antibody indicates immunity from HBV infection. After infection, most people are positive for anti-HBs and anti-HBc antibodies. In contrast, only anti-HBs antibody develops in persons who have been vaccinated against hepatitis B. Those who do not recover from HBV become chronically infected and remain positive for HBsAg (and anti-HBc). A small number (0.3% per year) eventually clear HBsAg and develop anti-HBs antibody (2,6).

Some individuals have anti-HBc antibody as the only HBV serologic marker. Isolated anti-HBc antibody can occur after HBV infection among persons who have recovered but whose anti-HBs antibody levels have waned or among persons who failed to develop anti-HBs antibody. HBV DNA is detected in <10% of persons with isolated anti-HBc antibody, and these persons are unlikely to be infectious to others. For most people with isolated anti-HBc antibody, the result appears to be a false positive. A primary anti-HBs antibody response develops in most of these individuals after a three-dose hepatitis B vaccine series. We have no data on response to vaccination for hemodialysis patients with this serologic pattern (2,6).

HBeAg can be detected in serum of those with acute or chronic HBV infection, usually appearing shortly after the appearance of anti-HBc. The presence of HBeAg correlates with viral replication, whereas anti-HBe correlates with the loss of replicating virus. All HBsAg-positive people should be considered infectious, regardless of HBeAg or anti-HBe status. HBV infection can also be detected using tests for HBV DNA. These tests are most commonly used for persons being treated with antivirals (2,6).

All hemodialysis patients should be screened for hepatitis B [HBsAg, anti-HBc total, anti-HBs, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT)] upon admission to the dialysis unit. It is important to note that in chronic uremia, the serum aminotransferases are spuriously low in chronic HBV infections and must not be relied upon to indicate which patients need hepatitis screening (4). Nonimmune individuals should be immunized and screening for HBsAg repeated monthly until seroconversion from vaccination has been documented. Individuals who are anti-HBs and anti-HBc positive require no additional HBV testing because they are immune. After vaccine-induced seroconversion to anti-HBs positive (≥10 mIU/mL) dialysis, patients should be screened annually for anti-HBs. A booster dose of vaccine should be given if anti-HBs declines to <10 mIU/mL, and annual testing should continue thereafter.

Since 1977, the recommendation has been that HBsAg-positive persons should be isolated in a separate room, using separate machines, equipment, instruments, and supplies. Staff members assigned to HBsAg-positive patients should not be assigned to HBV-susceptible patients during the same shift. Dialysis equipment assigned to HBsAg-positive patients must not be shared by HBV-susceptible patients, and the routine cleaning and disinfection of equipment and environmental surfaces is of paramount importance. HBV is viable for up to 7 days on environmental surfaces and has been detected in dialysis centers on clamps, scissors, dialysis machine controls, and doorknobs. Blood-contaminated surfaces are a reservoir for HBV transmission, and dialysis staff members must take great care not to transfer virus to patients from these contaminated surfaces by their hands or gloves or through contaminated supplies (6).

Hepatitis B Virus Vaccine Recommendations

HBV vaccination recommendations for susceptible hemodialysis patients and staff include documentation of baseline serologies followed by three intramuscular doses of vaccine, with the second and third doses given at 1 month and 6 months after the first dose. Because immunocompromised persons have lower vaccine response rates, both the Recombivax HB and Engerix-B vaccine formulations have separate, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, recommendations for predialysis versus dialysis-dependent persons. With Recombivax HB, dialysis-dependent patients should receive 40 μg in 1 mL at 0, 2, and 6 months, whereas the recommended Engerix schedule for dialysis patients is for 40 μg at 0, 1, 2, and 6 months. All doses should be administered in the deltoid by the intramuscular route. Since hepatitis B vaccine became available, no HBV infections have been reported among vaccinated hemodialysis patients if they maintained protective levels of antibody to HBV. Fifty percent to 70% of nonresponders will respond to three additional doses. For nonresponders after six doses of vaccine, no data support additional doses. Among successfully immunized hemodialysis patients whose antibody titers subsequently declined below protection, data show that most respond to a booster dose. Periodic hepatitis B antibody screening of vaccine responders in the hemodialysis unit should permit identification of individuals in need of a booster dose to maintain immunity (6,11).

HEPATITIS C VIRUS SCREENING

HEPATITIS C VIRUS SCREENING

Because morbidity and mortality rates are higher in HCV-infected hemodialysis patients, these individuals should be screened at initial entry to hemodialysis, and annually thereafter if they engage in high risk behaviors, including injection drug use, intranasal cocaine use, or are men who have sex with men. Screening should use both ALT and an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or the supplemental recombinant immunoassay (RIBA) that detects anti-HCV antibodies. The CDC has recommended monthly ALT screening for HCV-negative persons, regardless of risk factors, as early detection of an infection would permit consideration of therapy (FIGURE 21.3) (6). The EIA is at least 97% sensitive, but it does not distinguish between acute, chronic, or resolved HCV infection, and therefore, a positive antibody test should be followed by a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay for HCV, which is commonly used in clinical practice and commercially available. Persistent viremia with HCV defines chronicity, which is seen in some 85% of infections. After treatment, or after spontaneous viral clearance (which may occur in 15% to 45% of infected persons), a sustained virologic response (SVR) is defined by finding undetectable HCV by RT-PCR after a 12- (SVR12) or 24-week (SVR24) interval (26). Regardless of whether a hemodialysis patient with HCV is a candidate for specific HCV therapy, knowledge of this comorbidity allows the clinician to counsel the patient about prognosis and about basic health maintenance measures that may improve outcomes. HCV-infected persons should abstain from alcohol because it accelerates fibrosis progression; avoid excessive acetaminophen use; avoid behaviors such as sharing of needles, razor blades, or toothbrushes which may result in transmission of viral infection to others; and they should be immunized against both hepatitis A and B to prevent fulminant hepatitis superinfection (27). There is no vaccine available for prevention of HCV in 2015.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree