Hepatic Segmental Resections

William R. Jarnagin

Charbel Sandroussi

Paul D. Greig

Introduction

Better understanding of hepatic anatomy has been pivotal in the evolution of safe liver surgery (see Chapter 18 and Figs. 17.6, 18.6 and 23.1). Compared to lobar and extended lobar resections, segmental liver resections, where appropriate, allow preservation of liver parenchyma without compromising oncologic results. The ability to resect one or two segments rather than the entire lobe allows parenchymal preservation, which is critical in patients with diseased parenchyma and in those with extensive disease and/ or a high likelihood of requiring future liver directed therapy. The latter are particularly relevant in patients with metastatic disease. Segmental vascular inflow control may facilitate the resection by precisely mapping the transection plane, although this is not always possible. In addition, such anatomically based resections involving the removal of a hepatic segment confined by tumor-bearing portal tributaries may, in fact, be more sound from an oncologic standpoint.

Anatomy and Terminology

The segmental anatomy of the liver originated from the original descriptions of Couinaud in 1952. Couinaud’s work showed that the liver consists of eight independent segments, each with its own vascular inflow, hepatic venous outflow, and biliary drainage and each amenable to resection. These segments form the foundation of current hepatic nomenclature (Fig. 24.1A and B; see also Fig. 18.6). The Brisbane Terminology eliminates confusing terminology of lobes and sectors used in past descriptions of liver anatomy. The terms hemi-liver (first order division), section (second order division), and segments (third order division) are not interchangeable and provides common terminology for better communication among surgeons, radiologists, and other physicians.

The first order division separates the right (segments 5 to 8) and left (segments 1 to 4) hemi-livers (or liver) along the principal resection plane or Cantlie’s line, delineated by the middle hepatic vein (MHV), coursing along a line from the gallbladder fossa to the IVC. The second order division separates the right and left hemi-livers into liver

sections based on the portal distribution (i.e., the primary divisions of the right and left portal pedicles) and the hepatic venous drainage. The right liver is divided into right anterior (segments 5 and 8), and right posterior (segments 6 and 7) sections, separated by the right hepatic vein (RHV). The left liver is divided into left lateral (segments 2 and 3) and left medial (segments 4a and 4b) sections by the umbilical vein, which runs along a line delineated by the falciform ligament. Together, segments 2 and 3 are commonly, but erroneously, referred to as the left lateral segment.

sections based on the portal distribution (i.e., the primary divisions of the right and left portal pedicles) and the hepatic venous drainage. The right liver is divided into right anterior (segments 5 and 8), and right posterior (segments 6 and 7) sections, separated by the right hepatic vein (RHV). The left liver is divided into left lateral (segments 2 and 3) and left medial (segments 4a and 4b) sections by the umbilical vein, which runs along a line delineated by the falciform ligament. Together, segments 2 and 3 are commonly, but erroneously, referred to as the left lateral segment.

The third order division separates segments into segments (numbers 1 to 8) and is defined by hepatic arterial supply and biliary drainage (see Figs. 17.6 and 18.6).

Selection of Patients

Anatomically based resections should be the gold standard in most cases, excluding fenestration of liver cysts (see Chapter 28), wedge excisions of superficial lesions, and enucleation of certain lesions such as metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (see Chapter 25). A clear understanding of the patient’s segmental liver anatomy is essential to a safe, controlled resection. Segmental resections are not limited by indication nor by the presence of hepatic parenchymal disease.

Achieving a balance between parenchymal sparing resections and adequate tumor clearance is clearly an important consideration for all resections but is critical in patients with diseased livers. In patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), where cirrhosis is frequently present, segmental liver resection forms a bridge between the major hepatectomy and non-anatomic resection to preserve the maximum liver volume to prevent postoperative liver failure. Since HCC have a propensity for intraportal extension and dissemination, segmental resections, by removing the parenchyma supplied by the principal segmental portal vein branch, are likely to be more effective than non-anatomic resections from an oncologic standpoint. Segmental liver resection is also preferred in patients with multifocal colorectal metastasis treated extensively with preoperative chemotherapy, which frequently results in hepatic dysfunction and impaired regeneration due to steatosis (see Fig. 18.1).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

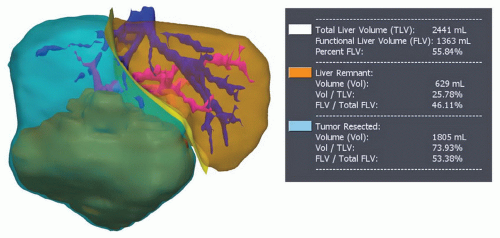

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGThe planning of a segmental-based resection must take into account anatomic variations and their relationship to the plane of transection (Fig. 24.2) (see Figs. 17.9, 19.2, and 21.1, 21.2, 21.3 and 21.4). Resection has been facilitated by the precision digital imaging provided by computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US), allowing interpretation of intrahepatic vascular and biliary anatomy (see Chapter 18) and the ability to manipulate and scroll through reconstructions in the axial, coronal, or sagittal planes using software such as picture archiving and communication system(PACS). With the appropriate protocol for arterial and venous enhancement, the third and fourth level vascular structures can be accurately defined. More sophisticated software is available that may facilitate the preoperative planning. These easily manipulated, three-dimensional reconstructions that create a virtual reproduction of the liver can be used to determine the proposed plane of transection, taking into account the minimum resection margin, and residual volume of liver (Fig. 24.3).

General Operative Principles

Preoperative Assessment and Anesthesia

The preoperative assessment and preparation of the patient for a liver resection are described in Chapter 18. Comorbidities should be identified and optimized. Careful assessment of liver function, particularly in those with intrinsic liver disease is important. Preoperative biliary decompression and/or portal vein embolization are infrequently required for patients undergoing segmental compared to more extensive resections (see Chapters 18, 19, 20, and 26). Particular attention should be paid to the reduction of the central venous pressure during transection in order to reduce blood loss, and measures to prevent hypothermia, infections, and venous thromboembolism are required.

Exposure and Mobilization

Segmental resections may be performed laparoscopically (see Chapter 31) or at laparotomy. For open resections, exposure can be achieved through a variety of incisions (see Figs. 18.7, 19.3 and 21.5), including right subcostal with midline extension (hockey-stick) or its modification (J-shaped), or a bilateral subcostal incision with (Mercedes incision) or without (chevron) midline extension. A long midline incision may be used for selected liver resections, particularly if combined with a left or sigmoid colon or rectal resection; thoracoabdominal is seldom required. Following laparotomy and general inspection, the liver is mobilized by transection of the obliterated umbilical vein and division of the falciform ligament as it triangulates onto the IVC to identify the origins of the hepatic veins (see Fig. 19.4). Mobilization of the right and left livers requires division of the triangular ligaments in order to free the liver fully from the hemidiaphragms. During the division of the lesser omentum (gastro-hepatic ligament), attention should be given to the presence of an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery (see Chapter 20). Full mobilization of the right liver requires division of the coronary ligaments; if resection of one of the posterior right segments is planned (6 and/or 7), then the right adrenal gland must be separated and allowed to retract into the retroperitoneum and dissection of the retrohepatic IVC must be performed, as one would for more extensive procedures (see Chapters 19 and 23, Figs. 19.5, 19.6, and 23.12).

Intraoperative Assessment

The intraoperative assessment of the liver requires correlation of the findings of inspection and palpation of the mobilized liver with those of the preoperative imaging (see Chapter 18). Intraoperative ultrasound is used to localize the lesion, confirm the preoperative imaging findings, and further stage the proposed remnant liver (see Fig. 18.9). Operative US of the liver may be valuable to identify venous tumor thrombus and to assess the proposed plane of transection and its three-dimensional relationship with major hepatic veins and portal triads. Anatomically based segmentectomy and subsegmentectomy by intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS)-guided finger compression has been described. With this technique, IOUS-guided finger compression of the vascular pedicle feeding the segment results in demarcation of the parenchyma, allowing a complete resection.

Transection Techniques

Over the years, the method of transecting the liver parenchyma has received much attention, and several devices have evolved for facilitating this portion of the operation (see Chapter 18). In truth, for resections that are anatomically based and performed using proper intraoperative management (i.e., low central venous pressure) and meticulous technique, the method of parenchymal transection is a secondary issue. The Cavitron ultrasonic aspirator (CUSA, Valleylab, Boulder, CO), which reduced blood loss compared with the clamp crushing technique in one study is now widely used for liver transection, even in cirrhotic livers. Clamp crushing, the conventional method of liver transection is used in some centers, and when properly done, allows precise delineation of intrahepatic vascular and biliary structures. The hydro-jet dissector (ERBE, Teubingen, Germany) is also widely used. The goal of all of these approaches is to selectively clear away the liver parenchymal tissue to expose the vascular and biliary structures for ligation. There is no evidence supporting one particular technique, and hence the technique chosen for transection is often dependent on local expertise.

Techniques that rely on destructive control of the parenchyma before division include linear cutting staplers, in-line radiofrequency ablation (Habib, Angiodynamics Queensbury NY) and bipolar cautery (Gyrus-Gyrus ACMI Southborough MA, Ligasure-Covidien Boulder CO). In-line radiofrequency ablation allows some surgeons to perform minor and major hepatectomies with low blood loss and low blood transfusion requirements. However, this device has raised serious concerns regarding preservation of venous drainage of the remnant liver and the risk of tissue necrosis and postoperative

bile leakage. The role of this technology probably is limited to small peripheral resections because of the substantial risk of bile duct injury when this instrument is used near the liver hilum and its inability to control bleeding from large venous branches. The Aquamantys [Salient Surgical Technologies (Formerly TissueLink Medical), Dover, NH] is another device that uses radiofrequency energy to divide the liver parenchyma, although in a more controlled fashion, combined with saline and configured as a bipolar tip for coagulating small pedicle and venous structures.

bile leakage. The role of this technology probably is limited to small peripheral resections because of the substantial risk of bile duct injury when this instrument is used near the liver hilum and its inability to control bleeding from large venous branches. The Aquamantys [Salient Surgical Technologies (Formerly TissueLink Medical), Dover, NH] is another device that uses radiofrequency energy to divide the liver parenchyma, although in a more controlled fashion, combined with saline and configured as a bipolar tip for coagulating small pedicle and venous structures.

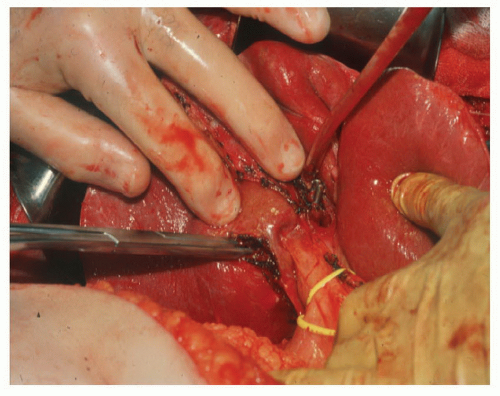

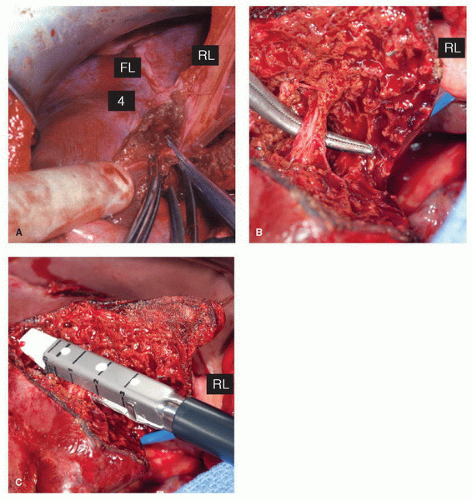

Pretransection vascular control is used by many surgeons, with potential oncologic and hemostasis implications. Early occlusion of the hepatic venous outflow of the resected segment(s) may reduce the risk of venous tumor emboli. Occlusion of the hepatic artery and portal vein to the segment(s) being resected facilitate the procedure by defining the line of division between ischemic segments to be removed and the viable remnant liver, thereby potentially reducing blood loss. Occlusion of the inflow to sectors of the right hemi-liver (6/7 and 5/8) or to the segments of the left lobe (2, 3, 4a, and 4b) can be performed either by dissection and division of the artery and vein outside the liver, leaving the transection of the hepatic duct and remaining hilar plate for later in the procedure, or by the Glissonian technique in which the sectoral or segmental pedicle is encircled (using either an anterior or posterior intrahepatic approach) and then exposed by incising the reflection of Glisson’s capsule and clearing away overlying parenchymal tissue. The portal triad to the segment or segments of interest can then be divided en masse, either by suture or a linear stapler (Fig. 24.4) (see also Fig. 21.14).

Procedures

Mono- and bi-segmental resections

Segment 1 Resection

Segment 1 is difficult to access, lying between the IVC and the left portal vein; it receives inflow predominantly from the left PV and HA (see Chapter 22). The biliary drainage of segment 1 is variable, and the segment 1 bile duct runs in the hilar plate and enters the posterior aspect of either left or right hepatic duct. Posteriorly, segment 1 rests on the IVC and most of its outflow is directly into the IVC via a series of small veins. Tumors arising in the caudate lobe are closely related to the posterior aspect of the left hepatic vein (LHV) and the middle hepatic vein (MHV).

The anatomy and technical aspects of resection of the caudate lobe are addressed in detail in Chapter 22.

Segment 2 or 3 Resection

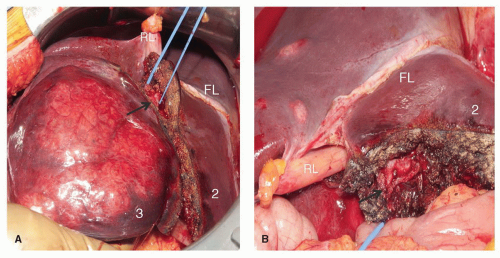

Isolated resection of segments 2 or 3 are possible, although given their frequent small size, they are often resected in combination as a left lateral sectionectomy. However, as more aggressive resections are pursued, particularly in patients with hepatic colorectal metastases, with bilobar lesions in chemotherapy-damaged livers, parenchymal sparing approaches are critical. When either of these segmentectomies is planned, the plane of resection is by either side of the LHV (left and posterior for segment 2 resection, and right and anterior for segment 3). The LHV can be sacrificed during isolated resection of segments 2 or 3, if necessary, provided the fissural or segment 4 vein is preserved; this branch , also referred to as the umbilical vein in Couinaud’s original description, runs in the liver parenchyma in a line delineated by the falciform ligament and is capable of draining the residual liver in the left lateral section. The inflow is approached on the left side of the falciform ligament, by incising the peritoneal reflection onto the liver and identifying the segment 2 (Fig. 24.5) or 3 portal pedicle (Fig. 24.6). Once the inflow is divided, the line of parenchymal transection becomes prominent between the ischemic segment to be resected and the normally perfused residual segment.

Combined Resection of Segments 2 and 3 (Left Lateral Sectionectomy)

The left lateral section is mobilized by division of the falciform ligament and the left triangular ligament (see Chapter 20). The extrahepatic portion of the LHV can be lengthened by dividing the fibrous tissue to the left of the IVC down to the level of the fissure for the ligamentum venosum. The ligamentum venosum is then ligated and divided as it enters the posterior aspect of the LHV allowing encircling of this vein if the point of entry into the MHV is extrahepatic. Dissection of the LHV outside the liver is generally recommended when tumor is in close proximity to its confluence with the IVC; otherwise, the isolation of the LHV is delayed until completion of the parenchymal transection. The inflow to segments 2 and 3 is usually isolated during transection of the parenchyma to the left of the falciform ligament, leaving the portal vein intact to supply segments 4a and 4b. Occasionally, pedicles to segment 2 and 3 can be identified and encircled outside the liver in the left side of the umbilical fissure; in some patients, these pedicles arise from a common trunk. The plane of parenchymal transection follows the falciform ligament. As the liver is divided, the portal structures to segment 2 and 3 will become apparent and can be electively ligated and divided. Once this is done and the parenchyma surrounding the LHV has been dissected, the vein can also be ligated and divided. The transection is completed by dividing the parenchyma anterior to the caudate lobe, in the fissure for the ligamentum venosum.

Segment 4 Resection

Segment 4, like the left lateral section, is frequently small in size and is not commonly resected in isolation, but rather as part of a larger procedure, such as central hepatectomy (see below and also Chapter 21) or segmentectomy 4b/5 for gallbladder carcinoma (see below and also Chapter 27). Segment 4a is very rarely resected alone, unlike segment 4b, given its peripheral location and easy access; although a segment 4a/8 resection for a high central tumor may be preferred over a central hepatectomy. Segment 4 is bordered posteriorly by the IVC, by the falciform ligament and umbilical vein on the left, and by the MHV on the right. Inferiorly, the left portal pedicle runs along the base of segment 4, just below the hilar plate (see Figs. 17.5A and 17.6). Inflow and biliary drainage are provided by branches of the main left portal pedicle within the umbilical fissure, directly opposite the pedicle branches to the left lateral section. Venous drainage of segment 4 is predominantly through the MHV, with a contribution from the umbilical vein.

After mobilization of the left liver and division of the falciform (see Chapter 20), the confluence of the LHV and the MHV with the IVC is identified (the left-middle groove identifies the apex of segment 4a), and the inflow pedicles are now approached. By incising the peritoneal reflection on the right side of the umbilical fissure, the segment 4a and 4b pedicles can be identified, encircled, and divided (see Fig. 27.9). Alternatively, these pedicles may be identified within the substance of the liver, just to the right of the falciform, and divided in the course of parenchymal transection (Fig. 24.7) (see also Figs. 19.10 and 21.8, 21.9 and 21.10). The parenchymal demarcation should be seen along the principal resection plane or Cantlie’s line on the right and the divided falciform ligament on the left, and transection of the parenchyma should proceed along these lines. As the resection proceeds toward the base of segment 4, care must be taken to avoid injury to the left portal pedicle, and particularly the left hepatic duct, which lies just below the hilar plate, anterior and cephalad to the left portal vein. As the transection continues superiorly to the level of the suprahepatic IVC, care should be taken to avoid injury to the major hepatic venous branches. The LHV and MHV commonly join within or just outside of the liver to form a common trunk, which then inserts into the IVC. The dissection of the right side is along Cantlie’s line, to the left of the MHV. Several tributaries to the MHV (the 4a and 4b veins) will need to be identified and ligated. If necessary, the MHV may be sacrificed during resection of segment 4, with the bulk of the venous drainage then provided by the LHV (segments 2 and 3) and the RHV (segments 5 and 8). Once the medial border of the hilar dissection has been reached the parenchymal transection is then done in a transverse plane to complete the separation of segment 4.

Segment 5 or 8 Resection

These segments comprise the right anterior sector or section. The bifurcation of the right portal pedicle into anterior and posterior pedicles is intrahepatic, and primary ligation prior to parenchymal transection can be difficult, especially for segment 8. Therefore some parenchymal transection along Cantlie’s line toward the pedicle is generally performed to expose the pedicles. The segment 5 pedicle emerges anteriorly and runs anteroinferiorly, while the segment 8 pedicle emerges posteriorly and runs superiorly. The axial plane of transection for an isolated segment 5 or segment 8 resection runs through the liver at the level of the bifurcation of the portal vein, with segment 5 below and segment 8 above this line. The medial and lateral limits of the resection are the MHV and the RHV, respectively.

Segment 5 Resection

Isolated segment 5 resection begins with division of the liver on the undersurface up the centre of the gallbladder fossa and anteriorly along Cantlie’s line half-way up toward the IVC. Continued parenchymal transection in this plane will ultimately lead to the major right portal pedicles. With careful dissection, the anterior pedicle, and its component branches to segment 5 and 8, are identified (see Fig. 27.13, which illustrates isolation of the segment 5 pedicle during resection of gallbladder cancer). In some

patients, the pedicle to segment 7 arises from the anterior sector; recognition of this anatomical variation is important in order to avoid compromising the integrity of this segment. The parenchyma between the MHV on the left and RHV on the right is then divided, up to the take of the segment 8 pedicle superiorly.

patients, the pedicle to segment 7 arises from the anterior sector; recognition of this anatomical variation is important in order to avoid compromising the integrity of this segment. The parenchyma between the MHV on the left and RHV on the right is then divided, up to the take of the segment 8 pedicle superiorly.

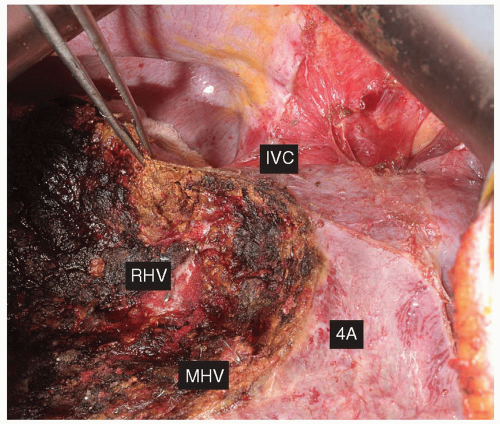

Segment 8 Resection

Isolated resection of segment 8 is challenging as there are few external landmarks delimiting its boundaries, which consist of the IVC posteriorly, Cantlie’s line or the MHV medially and the RHV laterally (Fig. 24.8). The segment 8 pedicle corresponds to the ascending division of the right anterior sectorial pedicle and is most commonly identified after initial division of liver parenchyma between segments 4 and 5 in the sagittal plane, along the level of the portal bifurcation. The horizontal transection should proceed in a coronal plane anterior to the RHV to its intersection with the sagittal plane that includes Cantlie’s line and the MHV down to the anterior surface of the IVC. Mobilization of the right liver, as one would do for a major right hepatectomy, is necessary to free the posterior aspect of segment 8 (see Chapter 19 and Figs. 19.5 and 19.6; see Chapter 23 and Figs. 23.12 and 23.13). Care must be taken during the parenchymal division to adhere to the correct transection plane posteriorly. This allows resection of all the liver in segment 8 while avoiding injury to the RHV.

Combined Resection of Segments 5 and 8

The combined resection of segments 5 and 8 constitutes an anterior sectionectomy, a procedure that can be performed in place of a right hepatectomy, when appropriate, provided the integrity of the procedure is not compromised from an oncologic standpoint. This procedure, and its counterpart posterior sectionectomy (resection of segments 6 and 7), are covered in detail in Chapter 23.

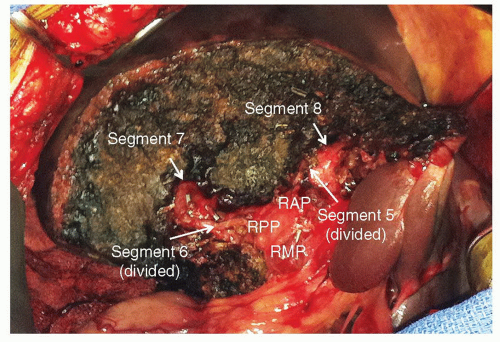

Segments 6 or 7 Resection

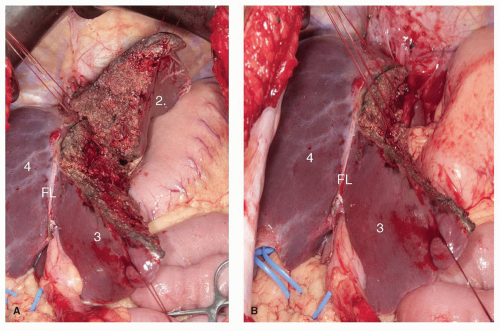

Segments 6 and 7 comprise the posterior section. The right posterior sectorial pedicle can be identified in the incisura dextra of Ganz, which corresponds to the horizontal fissure lateral to the gallbladder fossa. The pedicle to segment 6/7 can be isolated after initial division of the liver parenchyma in this area. Alternatively, the posterior sectoral branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein may be isolated with dissection within the proximal porta hepatis, but this approach is not always possible (see Figs. 23.7 and 23.17). The pedicle for an isolated resection of segment 6 or 7 is therefore usually

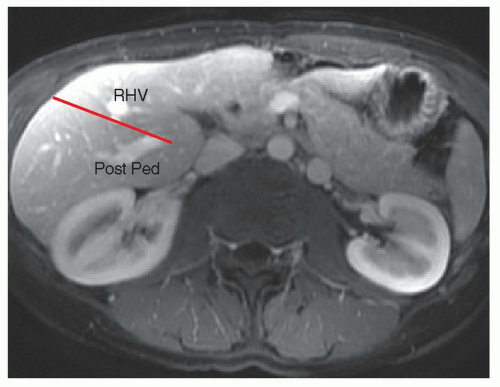

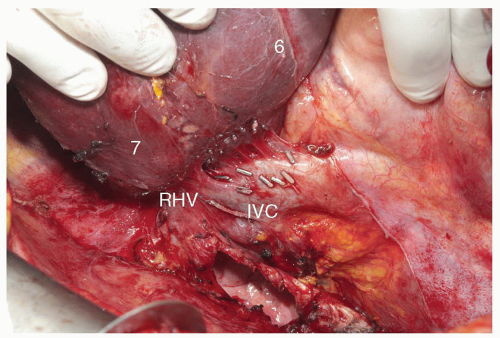

approached and controlled from within the liver, during parenchymal transection. It is important to bear in mind that the sagittal transection plane between the anterior and posterior sectors is oblique, approximately half way between the horizontal and vertical planes (Fig. 24.9). A resection of segment 6 or 7 requires complete mobilization of the right lobe of the liver with division of the retrohepatic veins draining into the IVC (Fig. 24.10). A combined resection of segments 6 and 7, or posterior sectionectomy, can be performed with preservation or sacrifice of the RHV.

approached and controlled from within the liver, during parenchymal transection. It is important to bear in mind that the sagittal transection plane between the anterior and posterior sectors is oblique, approximately half way between the horizontal and vertical planes (Fig. 24.9). A resection of segment 6 or 7 requires complete mobilization of the right lobe of the liver with division of the retrohepatic veins draining into the IVC (Fig. 24.10). A combined resection of segments 6 and 7, or posterior sectionectomy, can be performed with preservation or sacrifice of the RHV.

Segment 6 Resection

Isolated segment 6 resection is among the more straightforward of the isolated segmental resections, similar to resection of segment 3, given its very peripheral location. The resection begins with an oblique transection line along the incisura dextra of Ganz on the under surface of the liver and anteriorly approximately half-way toward the IVC, posterior to the plane of the RHV. The axial transection plane is at the level of the portal vein bifurcation. The posterior pedicle will be encountered medially, at the intersection of the transection planes. Care must be taken at this point to fully expose the pedicle branches and avoid injury to the segment 7 inflow.

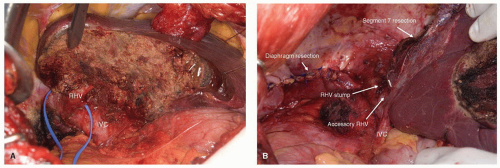

Segment 7 Resection

Isolated segment 7 can be performed with initial transection of the parenchyma in the axial plane, just above the bifurcation of the portal vein, which corresponds to the

horizontal resection line for a segment 6 resection. The resection continues medially to the lateral margin of the RHV; it is during this portion of the transection that the pedicle branches to segment 7 are encountered. The horizontal transection line runs obliquely through the liver lateral and posterior to the RHV (Fig. 24.11A). Resection of segment 7 can be done to include the RHV, provided there is a reasonable sized accessory hepatic vein draining segment 6 directly into the IVC (Fig. 24.11B).

horizontal resection line for a segment 6 resection. The resection continues medially to the lateral margin of the RHV; it is during this portion of the transection that the pedicle branches to segment 7 are encountered. The horizontal transection line runs obliquely through the liver lateral and posterior to the RHV (Fig. 24.11A). Resection of segment 7 can be done to include the RHV, provided there is a reasonable sized accessory hepatic vein draining segment 6 directly into the IVC (Fig. 24.11B).

Combined Resection of Segments 6 and 7

Resection of segments 6 and 7 together constitutes a right posterior sectionectomy, a procedure that can be performed as an alternative to a right hepatectomy when the anterior sector can be spared without compromising is the completeness of the resection, especially in patients with diseased parenchyma. Posterior sectionectomy is described in detail in Chapter 23.

Combined Resection of Segments 5 and 6

Resection of these two segments is very commonly performed. The vertical plane of transection is along Cantlie’s line between segments 4b and 5, to the right of the MHV from the edge of the liver to half-up toward the IVC, with the axial transection plane being at the level of the portal vein confluence, as it would be for an isolated segment 5 resection. The portal pedicles to segment 5 and 6 are usually divided during the parenchymal transection (Fig. 24.12). This resection requires mobilization of the right lobe from the retroperitoneum and diaphragm with division of the accessory hepatic veins in the anterior surface of the IVC. It is convenient to start the transection in the middle of the gallbladder fossa along Cantlie’s line up to the level of the right portal pedicle. The axial transection plane is then developed from the top of the vertical plane, with the pedicle branches identified and divided in the course of parenchymal transection. Branches of the RHV will be encountered and require division in the course of this resection. Once again, care must be taken to accurately identify the pertinent pedicles for division and avoid injury to adjacent structures.

Resection of Segments 4b and 5

Segmentectomy 4b and 5 is commonly performed for gallbladder cancer and combines the elements of resecting each segment individually, as described above. This procedure may include en bloc resection of the extrahepatic biliary tree and porta hepatis lymphatic tissue and is discussed in more detail in Chapter 27.

Resection of Segments 4, 5, and 8 (Central or Mesohepatectomy)

This resection is indicated primarily for large central tumors where an extended right or left hepatectomy risks leaving behind a liver remnant of insufficient volume. The technical aspects of central hepatectomy are described in detail in Chapter 21.

Recommended References and Readings

Abulkhir A, Limongelli P, Healey AJ, et al. Preoperative portal vein embolization for major liver resection: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:49-57.

Agrawal S, Belghiti J. Oncologic resection for malignant tumors of the liver. Ann Surg. 2011;253:656-665.

Ayav A, Jiao LR, Habib NA. Bloodless liver resection using radiofrequency energy. Dig Surg. 2007;24:314-317.

Ayav A, Jiao L, Dickinson R, et al. Liver resection with a new multiprobe bipolar radiofrequency device. Arch Surg. 2008;143:396-401.

Baer HU, Maddern GJ, Blumgart LH. New water-jet dissector: initial experience in hepatic surgery. Br J Surg. 1991;78:502-503.

Belghiti J, Ogata S. Preoperative optimization of the liver for resection in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:252-253.

Billingsley KG, Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, et al. Segment-oriented hepatic resection in the management of malignant neoplasms of the liver. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:471-481.

Bismuth H, Castaing D, Garden OJ. Segmental surgery of the liver. Surg Annu. 1988;20:291-310.

Bismuth H, Houssin D, Castaing D. Major and minor segmentectomies “reglees” in liver surgery. World J Surg. 1982;6(1):10-24.

Clavien PA, Selzner M, Rüdiger HA, et al. A prospective randomized study in 100 consecutive patients undergoing major liver resection with versus without ischemic preconditioning. Ann Surg. 2003;238:843-850.

Couinaud C. Segmental and lobar left hepatectomies. J Chir (Paris). 1952a;68:821-839.

Couinaud C. Segmental and lobar left hepatectomies; studies on anatomical conditions. J Chir (Paris). 1952b;68:697-715.

Couinaud C. Contribution of anatomical research to liver surgery. Fr Med. 1956;19:5-12.

Couinaud C. Surgical Anatomy of the Liver Revisited. Paris: C. Couinaud; 1989.

Curro G, Habib N, Jiao L, et al. Radiofrequency-assisted liver resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis: preliminary results. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3523-3525.

Fan ST, Lai EC, Lo CM, et al. Hepatectomy with an ultrasonic dissector for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:117-120.

Figueras J, Lopez-Ben S, Lladó L, et al. Hilar dissection versus the “glissonean” approach and stapling of the pedicle for major hepatectomies: a prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2003; 238:111-119.

Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Imamura H, et al. Prognostic impact of anatomic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2005;242:252-259.

Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N, et al. One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Arch Surg. 2003; 138:1198-1206.

Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1,803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397-406.

Kim J, Ahmad SA, Lowy AM, et al. Increased biliary fistulas after liver resection with the harmonic scalpel. Am Surg. 2003;69:815-819.

Kooby DA, Fong Y, Suriawinata A, et al. Impact of steatosis on perioperative outcome following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(8):1034-1044.

Launois B, Jamieson GG. The importance of Glisson’s capsule and its sheaths in the intrahepatic approach to resection of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;174:7-10.

Liau KH, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Segment-oriented approach to liver resection. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:543-561.

Lin TY. A simplified technique for hepatic resection: the crush method. Ann Surg. 1974;180:285-290.

Little JM, Hollands MJ. Impact of the CUSA and operative ultrasound on hepatic resection. HPB Surg. 1991;3:271-277.

Lupo L, Gallerani A, Panzera P, et al. Randomized clinical trial of radiofrequency-assisted versus clamp-crushing liver resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:287-291.

Machado MA, Herman P, Machado MC. A standardized technique for right segmental liver resections. Arch Surg. 2003;138:918-920.

Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kosuge T, et al. The value of ultrasonography for hepatic surgery. Hepatogastroenterology. 1991;38: 64-70.

Polk W, Fong Y, Karpeh M, et al. A technique for the use of cryosurgery to assist hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(2):171-176.

Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, et al. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19:59-71.

Takayama T, Makuuchi M, Kubota K, et al. Randomized comparison of ultrasonic vs clamp transection of the liver. Arch Surg. 2001; 136:922-928.

The Brisbane 2000. Terminology of liver anatomy and resections. HPB (Oxford). 2002;4:99-100.

Torzilli G, Procopio F, Cimino M, et al. Anatomical segmental and subsegmental resection of the liver for hepatocellular carcinoma: a new approach by means of ultrasound-guided vessel compression. Ann Surg. 2010;251:229-235.

Wakai T, Shirai Y, Sakata J, et al. Anatomic resection independently improves long-term survival in patients with T1-T2 hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1356-1365.

Hepatic Segmental Resections

William R. Jarnagin

Charbel Sandroussi

Paul D. Greig

Introduction

Better understanding of hepatic anatomy has been pivotal in the evolution of safe liver surgery (see Chapter 18 and Figs. 17.6, 18.6 and 23.1). Compared to lobar and extended lobar resections, segmental liver resections, where appropriate, allow preservation of liver parenchyma without compromising oncologic results. The ability to resect one or two segments rather than the entire lobe allows parenchymal preservation, which is critical in patients with diseased parenchyma and in those with extensive disease and/ or a high likelihood of requiring future liver directed therapy. The latter are particularly relevant in patients with metastatic disease. Segmental vascular inflow control may facilitate the resection by precisely mapping the transection plane, although this is not always possible. In addition, such anatomically based resections involving the removal of a hepatic segment confined by tumor-bearing portal tributaries may, in fact, be more sound from an oncologic standpoint.

Anatomy and Terminology

The segmental anatomy of the liver originated from the original descriptions of Couinaud in 1952. Couinaud’s work showed that the liver consists of eight independent segments, each with its own vascular inflow, hepatic venous outflow, and biliary drainage and each amenable to resection. These segments form the foundation of current hepatic nomenclature (Fig. 24.1A and B; see also Fig. 18.6). The Brisbane Terminology eliminates confusing terminology of lobes and sectors used in past descriptions of liver anatomy. The terms hemi-liver (first order division), section (second order division), and segments (third order division) are not interchangeable and provides common terminology for better communication among surgeons, radiologists, and other physicians.

The first order division separates the right (segments 5 to 8) and left (segments 1 to 4) hemi-livers (or liver) along the principal resection plane or Cantlie’s line, delineated by the middle hepatic vein (MHV), coursing along a line from the gallbladder fossa to the IVC. The second order division separates the right and left hemi-livers into liver

sections based on the portal distribution (i.e., the primary divisions of the right and left portal pedicles) and the hepatic venous drainage. The right liver is divided into right anterior (segments 5 and 8), and right posterior (segments 6 and 7) sections, separated by the right hepatic vein (RHV). The left liver is divided into left lateral (segments 2 and 3) and left medial (segments 4a and 4b) sections by the umbilical vein, which runs along a line delineated by the falciform ligament. Together, segments 2 and 3 are commonly, but erroneously, referred to as the left lateral segment.

sections based on the portal distribution (i.e., the primary divisions of the right and left portal pedicles) and the hepatic venous drainage. The right liver is divided into right anterior (segments 5 and 8), and right posterior (segments 6 and 7) sections, separated by the right hepatic vein (RHV). The left liver is divided into left lateral (segments 2 and 3) and left medial (segments 4a and 4b) sections by the umbilical vein, which runs along a line delineated by the falciform ligament. Together, segments 2 and 3 are commonly, but erroneously, referred to as the left lateral segment.

The third order division separates segments into segments (numbers 1 to 8) and is defined by hepatic arterial supply and biliary drainage (see Figs. 17.6 and 18.6).

Selection of Patients

Anatomically based resections should be the gold standard in most cases, excluding fenestration of liver cysts (see Chapter 28), wedge excisions of superficial lesions, and enucleation of certain lesions such as metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (see Chapter 25). A clear understanding of the patient’s segmental liver anatomy is essential to a safe, controlled resection. Segmental resections are not limited by indication nor by the presence of hepatic parenchymal disease.

Achieving a balance between parenchymal sparing resections and adequate tumor clearance is clearly an important consideration for all resections but is critical in patients with diseased livers. In patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), where cirrhosis is frequently present, segmental liver resection forms a bridge between the major hepatectomy and non-anatomic resection to preserve the maximum liver volume to prevent postoperative liver failure. Since HCC have a propensity for intraportal extension and dissemination, segmental resections, by removing the parenchyma supplied by the principal segmental portal vein branch, are likely to be more effective than non-anatomic resections from an oncologic standpoint. Segmental liver resection is also preferred in patients with multifocal colorectal metastasis treated extensively with preoperative chemotherapy, which frequently results in hepatic dysfunction and impaired regeneration due to steatosis (see Fig. 18.1).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGThe planning of a segmental-based resection must take into account anatomic variations and their relationship to the plane of transection (Fig. 24.2) (see Figs. 17.9, 19.2, and 21.1, 21.2, 21.3 and 21.4). Resection has been facilitated by the precision digital imaging provided by computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US), allowing interpretation of intrahepatic vascular and biliary anatomy (see Chapter 18) and the ability to manipulate and scroll through reconstructions in the axial, coronal, or sagittal planes using software such as picture archiving and communication system

(PACS). With the appropriate protocol for arterial and venous enhancement, the third and fourth level vascular structures can be accurately defined. More sophisticated software is available that may facilitate the preoperative planning. These easily manipulated, three-dimensional reconstructions that create a virtual reproduction of the liver can be used to determine the proposed plane of transection, taking into account the minimum resection margin, and residual volume of liver (Fig. 24.3).

(PACS). With the appropriate protocol for arterial and venous enhancement, the third and fourth level vascular structures can be accurately defined. More sophisticated software is available that may facilitate the preoperative planning. These easily manipulated, three-dimensional reconstructions that create a virtual reproduction of the liver can be used to determine the proposed plane of transection, taking into account the minimum resection margin, and residual volume of liver (Fig. 24.3).

General Operative Principles

Preoperative Assessment and Anesthesia

The preoperative assessment and preparation of the patient for a liver resection are described in Chapter 18. Comorbidities should be identified and optimized. Careful assessment of liver function, particularly in those with intrinsic liver disease is important. Preoperative biliary decompression and/or portal vein embolization are infrequently required for patients undergoing segmental compared to more extensive resections (see Chapters 18, 19, 20, and 26). Particular attention should be paid to the reduction of the central venous pressure during transection in order to reduce blood loss, and measures to prevent hypothermia, infections, and venous thromboembolism are required.

Exposure and Mobilization

Segmental resections may be performed laparoscopically (see Chapter 31) or at laparotomy. For open resections, exposure can be achieved through a variety of incisions (see Figs. 18.7, 19.3 and 21.5), including right subcostal with midline extension (hockey-stick) or its modification (J-shaped), or a bilateral subcostal incision with (Mercedes incision) or without (chevron) midline extension. A long midline incision may be used for selected liver resections, particularly if combined with a left or sigmoid colon or rectal resection; thoracoabdominal is seldom required. Following laparotomy and general inspection, the liver is mobilized by transection of the obliterated umbilical vein and division of the falciform ligament as it triangulates onto the IVC to identify the origins of the hepatic veins (see Fig. 19.4). Mobilization of the right and left livers requires division of the triangular ligaments in order to free the liver fully from the hemidiaphragms. During the division of the lesser omentum (gastro-hepatic ligament), attention should be given to the presence of an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery (see Chapter 20). Full mobilization of the right liver requires division of the coronary ligaments; if resection of one of the posterior right segments is planned (6 and/or 7), then the right adrenal gland must be separated and allowed to retract into the retroperitoneum and dissection of the retrohepatic IVC must be performed, as one would for more extensive procedures (see Chapters 19 and 23, Figs. 19.5, 19.6, and 23.12).

Intraoperative Assessment

The intraoperative assessment of the liver requires correlation of the findings of inspection and palpation of the mobilized liver with those of the preoperative imaging (see Chapter 18). Intraoperative ultrasound is used to localize the lesion, confirm the preoperative imaging findings, and further stage the proposed remnant liver (see Fig. 18.9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree