Hepatic Caudate Resection

Michael G. House

Introduction

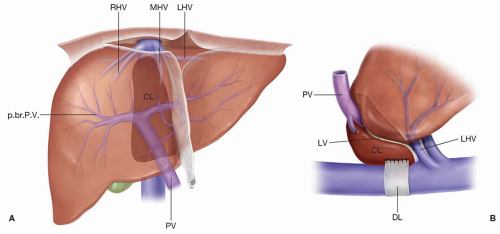

The caudate lobe (segment I) lies posterior to the hilum and anterior to the inferior vena cava (IVC) (Fig. 22.1; see also Fig. 18.6) and is composed of three parts: the caudate lobe proper or Spiegel lobe extends to the left of the vena cava and under the lesser omentum, which separates it from segments II and III; the paracaval portion of the caudate lies anterior to the IVC and extends cephalad to the roots of the major hepatic veins; the caudate process is located between the main right glissonian pedicle and the IVC and fuses with segment VI of the right lobe.

The caudate lobe is surrounded by major vascular structures, which can make resection technically challenging. The posterior and superior borders are formed by the retrohepatic IVC and the confluence of the left and middle hepatic veins, respectively, while the left portal vein and hepatic hilum serve as the anterior border. The ligamentum venosum, the obliterated ductus venosus, courses along the medial aspect of the caudate from the umbilical portion of the left portal vein to the inferior border of the left hepatic vein. The rightward extent of the caudate is typically small and is indistinctly delimited by the posterior surface of segment IV and the medial surfaces of segments VI and VII. The middle hepatic vein is adjacent to the right side of the caudate, and may be the source of significant hemorrhage if injured during resection. The posterior edge of the caudate on the left has a fibrous component (the hepatocaval ligament or dorsal ligament) that attaches to the crus of the diaphragm and extends posteriorly behind the vena cava to join segment VII on the right side of the IVC. In a large proportion of patients, this fibrous tissue is replaced by hepatic parenchyma (Fig. 22.1).

Both the left and right portal pedicles contribute to the blood supply and biliary drainage of the caudate. Portal venous blood is supplied by two to three branches from the left portal vein and the main right or right posterior sectoral portal vein. From a practical standpoint, the left branch is much more constant and supplies a greater proportion of the lobe than the right branch(es). During left or extended left hepatectomy, it is important to identify and spare this left-sided branch if the caudate is to be preserved. The caudate is the only hepatic segment whose entire hepatic venous drainage

is directly into the IVC, through a variable number of short venous branches that completely bypasses the major hepatic veins (Fig. 22.2).

is directly into the IVC, through a variable number of short venous branches that completely bypasses the major hepatic veins (Fig. 22.2).

Many anatomical features of the caudate are thus unique relative to the other hepatic segments. Consideration of its embryogenesis provides a clearer understanding of the caudate lobe anatomy in the adult (Fig. 22.3). During the second trimester of fetal life, the persistent left umbilical vein enters the liver via the umbilical fissure and empties into the left portal vein. The ductus venosus is suspended within the dorsal mesentery of the liver and shunts placental blood from the left portal vein directly into the vena cava. As the liver enlarges and rotates counterclockwise, a small portion extends behind the ductus venosus mesentery anterior to the IVC. The extrahepatic portion of the ductus venosus and its mesentery progressively shorten, and the caudate lobe arrives at its final position between the IVC and the left portal triad. The ductus venosus obliterates shortly after birth and persists as the ligamentum venosum.

Safe resection of the caudate lobe requires resolute preoperative cross-sectional imaging to determine the anatomic relationships between any target lesion(s) and the major inflow and outflow vessels within the liver and the IVC. The natural confinement of the caudate between the vena cava posteriorly and the left portal vein and middle

and left hepatic veins anteriorly and superiorly contributes to the technical difficulty of caudate resection. Isolated caudate hepatectomy, using an open technique for a large hepatic adenoma, was first described by Lerut et al. in 1990. Even though operative parenchymal transection techniques and pre- and intraoperative imaging have improved over the past two decades, the underlying principles guiding careful hepatectomy originate with mastery of the extra- and intrahepatic anatomy. Laparoscopic caudate hepatectomy has recently been reported, but the technical considerations necessary for a safe open resection should not be compromised. This chapter focuses on the technical aspects of performing a caudate resection, either in isolation as a monosegmentectomy or in combination with a partial hepatectomy, the latter being the most common.

and left hepatic veins anteriorly and superiorly contributes to the technical difficulty of caudate resection. Isolated caudate hepatectomy, using an open technique for a large hepatic adenoma, was first described by Lerut et al. in 1990. Even though operative parenchymal transection techniques and pre- and intraoperative imaging have improved over the past two decades, the underlying principles guiding careful hepatectomy originate with mastery of the extra- and intrahepatic anatomy. Laparoscopic caudate hepatectomy has recently been reported, but the technical considerations necessary for a safe open resection should not be compromised. This chapter focuses on the technical aspects of performing a caudate resection, either in isolation as a monosegmentectomy or in combination with a partial hepatectomy, the latter being the most common.

INDICATIONS

INDICATIONSWhen indicated, benign and malignant tumors within the caudate should be considered for operative resection. Depending on location, tumors isolated to segment I are often amenable to monosegmentectomy without the need for contiguous major hepatectomy. Large solitary, benign tumors within the caudate (e.g., hepatic adenoma, vascular malformation, cysts, etc.) can present with upper abdominal pain or symptoms of gastric impingement. Compression of the IVC can occur, but complete occlusion is uncommon, especially with benign tumors. Primary and secondary (i.e., metastatic) cancers of the liver can present within the caudate either as uni- or multifocal disease. Liver directed therapies aimed at tumor downsizing, for example, hepatic artery embolization, are applicable for palliative situations. Extrahepatic tumors arising from the stomach, duodenum, or retroperitoneal organs can invade the caudate directly and might be amenable to en bloc resection. Perihilar and intrahepatic bile duct cancers that involve the left hepatic ducts require caudate resection, typically in continuity with a major hepatectomy, for optimal tumor clearance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree