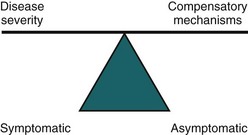

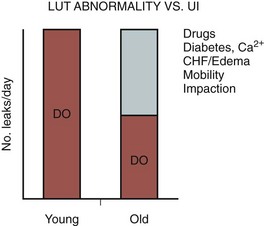

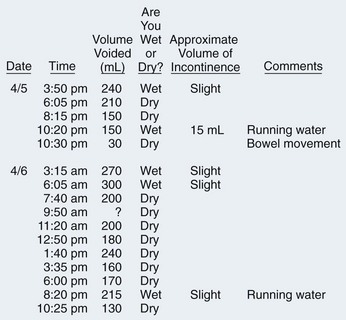

Neil M. Resnick, MD, Stasa D. Tadic, MD, MS, Subbarao V. Yalla, MD Urinary incontinence is a major problem for the elderly (Chang et al, 2008). It afflicts 15% to 30% of older people living at home, one third of those in acute-care settings, and half of those in nursing homes (Fantl et al, 1996; McGrother, 1998). It predisposes to perineal rashes, pressure ulcers, urinary tract infections, urosepsis, falls, and fractures (Fantl et al, 1996; Tromp et al, 1998; Brown et al, 2000; Parsons et al, 2009). It is associated with embarrassment, stigmatization, isolation, depression, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, and risk of institutionalization (Fantl et al, 1996; Farage et al, 2008; Angner et al, 2009). Also, it cost more than $26 billion to manage incontinence in America’s elderly in 1995, the last time primary data was collected (Wagner and Hu, 1998). This amount exceeded the amount devoted to dialysis and coronary bypass surgery combined. Despite these considerations, geriatric incontinence remains neglected by patients and physicians alike. Providers and older patients alike often neglect incontinence or dismiss it as a normal part of growing old (Branch et al, 1994; Mann et al, 2000; Chang et al, 2008; Lawhorne et al, 2008), but it is abnormal at any age (Resnick, 1988; Herzog and Fultz, 1990; Fantl et al, 1996). Although its prevalence increases, at no age does incontinence affect the majority of individuals, even over age 85 (Wetle et al, 1995). Moreover, its increased prevalence relates more to age-associated diseases and functional impairments than to age itself (Resnick et al, 1988; Herzog and Fultz, 1990; Resnick et al, 1995; Wetle et al, 1995). Regardless, incontinence is usually treatable and often curable at all ages, even in frail elderly (Ouslander and Schnelle, 1995; Resnick, 1995; Wagg and Malone-Lee, 1998; Weinberger et al, 1999), but the approach must differ significantly from that used in younger patients. In addition, the lower urinary tract changes with age, even in the absence of disease. Data from continent elderly are sparse and longitudinal data virtually nonexistent. However, it appears that although bladder capacity does not change with age (Pfisterer et al, 2006b), bladder sensation, contractility, and the ability to postpone voiding decline in both sexes, while urethral length and maximum closure pressure, as well as striated muscle cells in the rhabdosphincter and urogenital diaphragm, probably decline with age in women (Diokno et al, 1988; Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1995; Strasser et al, 1999; Perucchini et al, 2002; Pfisterer et al, 2006a, 2006b; Trowbridge et al, 2007; Betschart et al, 2008). The prostate enlarges in most men, and appears to cause urodynamic obstruction in half (Resnick et al, 1995). In both sexes, the prevalence of involuntary detrusor contractions increases, whereas the postvoid residual (PVR) volume probably increases but to no more than 50 to 100 mL (Diokno et al, 1988; Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1995; Bonde et al, 1996). In addition, the elderly often excrete most of their fluid intake at night, even in the absence of venous insufficiency, renal disease, heart failure, or prostatism (Miller, 2000; Morgan et al, 2000). This fact, coupled with an age-associated increase in sleep disorders, leads to one to two episodes of nocturia in the majority of healthy elderly (Miller, 2000; Morgan et al, 2000). Finally, at the cellular level, detrusor smooth muscle develops a “dense band pattern” characterized by dense sarcolemmal bands with depleted caveolae (Elbadawi et al, 1993a, 1993b, 1997a). This depletion may mediate the age-related decline in bladder contractility. In addition, an “incomplete dysjunction pattern” develops, characterized by scattered protrusion junctions, albeit not in chains; these changes may underlie the high prevalence of involuntary detrusor contractions (vide infra) (Resnick et al, 1995; Hailemariam et al, 1997; Elbadawi et al, 1997a). None of these age-related changes causes incontinence, but they do predispose to it. This predisposition, coupled with the increased likelihood that an older person will encounter an additional pathologic, physiologic, or pharmacologic insult, explains why the elderly are so likely to become incontinent. The implications are equally important. The onset or exacerbation of incontinence in an older person is probably due to precipitant(s) outside the lower urinary tract that are amenable to medical intervention. Furthermore, treatment of the precipitant(s) alone may be sufficient to restore continence, even if there is coexistent urinary tract dysfunction. For instance, flare of hip arthritis in a woman with age-related detrusor overactivity may be sufficient to convert her urinary urgency into incontinence. Treatment of the arthritis, rather than the involuntary detrusor contractions, will not only restore continence but also lessen pain and improve mobility. These principles, depicted in Figures 76-1 and 76-2 (Resnick, 1996; Resnick and Marcantonio, 1997), provide the rationale in the older patient for adding a set of transient causes to the established lower urinary tract causes of incontinence. Because of their frequency, ready reversibility, and association with morbidity beyond incontinence, the transient causes are discussed first. (From Resnick NM. An 89-year-old woman with urinary incontinence. JAMA 1996;276:1832–40.) (From Resnick NM, Marcantonio ER. How should clinical care of the aged differ? Lancet 1997;350:1157–58.) Incontinence is transient in up to one third of community-dwelling elderly and in up to half of acutely hospitalized patients (Resnick, 1988; Herzog and Fultz, 1990). Although most of the transient causes lie outside the lower urinary tract, three points warrant emphasis. First, the risk of transient incontinence is increased if, in addition to physiologic changes of the lower urinary tract, the older person also suffers from pathologic changes. Anticholinergic agents are more likely to cause overflow incontinence in persons with a weak or obstructed bladder, while excess urine output is more likely to cause urge incontinence in persons with detrusor overactivity and/or impaired mobility (Fantl et al, 1990; Diokno et al, 1991). Second, although termed “transient,” these causes of incontinence may persist if left untreated and cannot be dismissed merely because incontinence is longstanding. Third, similar to the situation for established causes (vide infra), identification of “the most common cause” is of little value. The likelihood of each cause depends on the individual, the clinical setting (community, acute hospital, nursing home), and referral pattern. Moreover, geriatric incontinence is rarely due to just one of these causes. Trying to disentangle which of the multiple abnormalities is “the” cause is more useful for metaphysics than for clinical practice. The causes of transient incontinence can be recalled easily using the mnemonic “DIAPERS” (Table 76–1). In the setting of delirium (an acute and fluctuating confusional state due to virtually any drug or acute illness), incontinence is merely an associated symptom that abates once the underlying cause of confusion is identified and treated. The patient needs medical rather than bladder management (Resnick, 1988). Table 76–1 Causes of Transient Incontinence Adapted from Resnick NM. Urinary incontinence in the elderly. Med Grand Rounds 1984;3:281–90. Symptomatic urinary tract infection causes transient incontinence when dysuria and urgency are so prominent that the older person is unable to reach the toilet before voiding. Asymptomatic bacteriuria, which is much more common in the elderly, does not cause incontinence (Brocklehurst et al, 1968; Resnick, 1988; Baldassare and Kaye, 1991; Ouslander et al, 1995). Because illness can present atypically in older patients, however, incontinence is occasionally the only atypical symptom of a urinary tract infection (UTI). Thus, if otherwise asymptomatic bacteriuria is found on initial evaluation, it should be treated and the result recorded in the patient’s record to prevent future futile therapy. Atrophic urethritis/vaginitis frequently causes lower urinary tract symptoms, including incontinence. Up to 80% of elderly women attending an incontinence clinic have atrophic vaginitis, characterized by vaginal mucosal atrophy, friability, erosions, and punctate hemorrhages (Robinson and Brocklehurst, 1984). Incontinence associated with this entity usually is associated with urgency and, occasionally, a sense of “scalding” dysuria that mimics a urinary tract infection, but both symptoms may be unimpressive. In demented individuals, atrophic vaginitis may present as agitation. Atrophic vaginitis also can exacerbate stress incontinence. The importance of recognizing atrophic vaginitis is that it may respond to low-dose estrogen (Fantl et al, 1996; Cardozo et al, 2004). Moreover, as for other causes of transient incontinence, treatment has additional benefits; in the case of atrophic urethritis, treatment ameliorates dyspareunia and reduces the frequency of recurrent cystitis (Resnick, 1988; Raz and Stamm, 1993; Cardozo et al, 1998; Eriksen, 1999). Reports from two large-scale randomized prospective trials, however, have recently challenged long-standing assumptions about the benefits and risks of hormone therapy. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) randomized more than 27,000 women, aged 50 to 79 years, to oral conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg, with or without medroxyprogesterone (MPA) 2.5 mg (Hendrix et al, 2005). The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) randomized nearly 2800 postmenopausal women of the same age to the same regimen (Grady et al, 2001). Both studies found that hormone therapy was associated with worsening of pre-existing incontinence. WHI investigators also found that hormone therapy, whether prescribed as CEE alone or with MPA, was associated with increased incidence of new incontinence. Because both studies also found that hormone therapy did not protect against heart disease, they advised against using hormone therapy for urinary incontinence. In trying to apply the results of the WHI and HERS trials, several caveats should be noted. Postmenopausal hormone levels differ substantially, and in some individuals they are similar to levels seen in the follicular phase of premenopausal women (Kuchel et al, 2001). Tissue sensitivity also varies. Thus it is surprising that neither WHI nor HERS randomized or stratified results by the presence or absence of atrophic vaginitis, nor did investigators examine patients to determine whether the dose administered was sufficient to treat the condition if it was present. Dropout rates in WHI were also high: 42% in the combined hormone therapy group and 54% in the estrogen-alone group. In addition, incontinence data were based on self-report, which can be problematic in older adults, both for reproducibility and for determining the type of incontinence (Resnick et al, 1994; Kirschner-Hermanns et al, 1998). Urodynamic testing was not performed. Moreover, although drugs used to treat heart disease in such patients can cause or exacerbate incontinence (e.g., diuretics, α blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), their impact was not reported. Finally, other hormone doses, types, and routes of administration were not evaluated. For example, a recent randomized placebo-controlled study with ultralow-dose transdermal estrogen (0.014 mg) revealed no substantial effect on either the frequency of incontinence or the risk of developing at least weekly incontinence (Waetjen et al, 2005). There is less evidence available from recent studies of nursing home patients, but limitations of sample size; selection bias; route, dose adequacy, and type of hormone used; and characterization and stratification by type of urinary infection (UI) all similarly preclude meaningful conclusions (DuBeau, 2001; Ouslander et al, 2001a). The apparent lack of efficacy for conjugated equine estrogen demonstrated in these two studies, as well as the risks associated with long-term use of higher doses, must be balanced against the other benefits cited above—the lower doses and shorter duration of treatment advised for treatment of atrophic vaginitis, and the shorter life expectancy of many older women in whom the prevalence and severity of atrophic vaginitis are highest. Moreover, data from other randomized double-blind trials, which employed different estrogen preparations (estriol, estradiol, or quinestradol), demonstrated significant reduction in incontinence among nursing home residents (Judge, 1969) and postmenopausal women with sensory urge incontinence (Walter et al, 1978; Moehrer et al, 2003). Thus clinical judgment is warranted, and local administration of other types of estrogen may be best. Unfortunately, the use of vaginal estrogen has not yet been well-studied. With adequate treatment, symptoms of atrophic vaginitis remit in a few days to several weeks, but the intracellular response takes longer (Semmens et al, 1985). The duration of therapy has not been well established (Pandit and Ouslander, 1997). One approach is to insert a ring containing estradiol. The advantage is that it is small and delivers the dose locally. Because it does not increase systemic estrogen concentrations, it is often considered for women with a past history of breast cancer. The disadvantage is that, despite its small size, it is not always feasible or well tolerated by frail older women, especially those with pronounced vaginal stenosis. Another option is to administer a low dose of estradiol orally or vaginally for 1 to 2 months and then taper it. Most patients probably can be weaned to a dose given as infrequently as 2 to 4 times per month. After 6 months, estrogen can be discontinued entirely in some patients, but recrudescence is common. Because the dose is low and given briefly, the carcinogenic effect is likely slight, if any. However, if long-term treatment is selected, a progestin probably should be added if the patient has a uterus. Hormone treatment (except for administration by a vaginal ring) is contraindicated for women with a history of breast cancer. For those without such a history, mammography should be performed prior to initiating hormone therapy. There appears to be a slightly increased risk of breast cancer among women using oral estrogen daily for more than 5 years, but fortunately, such high-dose, frequent, and long-term therapy is rarely required. Pharmaceuticals are one of the most common causes of geriatric incontinence, precipitating leakage by a variety of mechanisms (Table 76–2 and Tsakiris et al, 2008). Experts often cite dosages and serum levels below which side effects are uncommon. Unfortunately, such rules are of limited use in the elderly, because they are generally derived from studies of healthy younger persons who have no other diseases and take no other medications. Of note, many of these agents also are used in the treatment of incontinence, underscoring the fact that most medications are “double-edged swords” for the elderly. Table 76–2 Commonly Used Medications That May Affect Continence COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. * Examples include amlodipine (Norvasc), nifedipine, nicardipine, isradipine, felodipine, nimodipine. Adapted from Resnick NM. Geriatric medicine. In: Isselbacher KJ, Braunwald E, Wilson JD, Martin JB, Fauci AS, Kasper DJ, editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. p. 34. Long-acting sedative/hypnotics, whose half-life can exceed 100 hours, are associated not only with incontinence (Landi et al, 2002) but also with falling, hip fractures, driving accidents, depression, and confusion. Alcohol causes similar problems, but, for a variety of reasons, physicians frequently fail to identify alcohol use by older people as a source of symptoms, including incontinence. Sequelae of alcohol abuse are often absent or attributed to other causes. In addition, because of age-related alterations in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of alcohol disposal, as well as interactions with other commonly used drugs, as few as one or two drinks can pose a problem for older individuals. Because anticholinergic agents are prescribed so often for the elderly, and are used even without prescription (e.g., sedating antihistamines used for allergies, coryza, and insomnia), it is important to ask about them. They cause or contribute to incontinence in several ways. In addition to provoking overt urinary retention, these agents often induce subclinical retention. The resultant decrease in available bladder capacity (i.e., total capacity minus residual) allows it to be reached more quickly, exacerbating incontinence due to DO, as well as that due to functional impairment. By increasing bladder capacity (and often residual volume), anticholinergic agents also may aggravate leakage due to stress incontinence by further increasing the challenge to the sphincter mechanism. Additionally, many of these drugs decrease mobility (e.g., antipsychotics that induce extrapyramidal stiffness) and precipitate confusion. Finally, several agents intensify the dry mouth that many elderly already suffer owing to an age-related decrease in salivary gland function; the resultant increased fluid intake contributes to incontinence. Attempts should be made to discontinue anticholinergic agents, or to substitute with ones having less anticholinergic effect (e.g., a selective serotonin uptake inhibitor [SSRI] for a tricyclic antidepressant; risperidone for chlorpromazine). Limited data suggest that bethanechol may be useful for nonobstructed patients whose urinary retention is associated with use of an anticholinergic that cannot be discontinued (Everett, 1975). By blocking receptors at the bladder neck, α-adrenergic antagonists (many antihypertensives) may induce stress incontinence in older women (Mathew et al, 1988; Marshall and Beevers, 1996) in whom urethral length and closure pressure decline with age. Because hypertension affects half of the elderly, use of these agents may increase. Before considering interventions for stress incontinence in such women, one should substitute an alternative agent and reevaluate the incontinence. A few reports impugn cholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil (Aricept) or rivastigmine, as a cause of urinary incontinence (Hashimoto et al, 2000; Starr, 2007). The association is plausible, because these agents block the breakdown of acetylcholine within the neuroeffector junctional cleft. However, the incontinence often ceases even if the drug is continued, the number of cases is small, and the descriptions and evaluations of these cases are sparse. In addition, prospective trials in which these agents were evaluated for their cognitive impact did not note an increase in incontinence. Nonetheless, the association has not been well-evaluated to date, and because incontinence may improve or resolve on decreasing the drug dose or discontinuation, such an association is worth keeping in mind. Restricted mobility commonly contributes to geriatric incontinence. It can result from numerous treatable conditions, including arthritis, hip deformity, deconditioning, postural or postprandial hypotension, claudication, spinal stenosis, heart failure, poor eyesight, fear of falling, stroke, foot problems, drug-induced disequilibrium or confusion, or being restrained in a bed or chair (Resnick, 2004). A careful search will often identify these or other correctable causes. If not, a urinal or bedside commode may still improve or resolve the incontinence. Finally, stool impaction is implicated as a cause of urinary incontinence in up to 10% of older patients admitted to acute hospitals or referred to incontinence clinics (Resnick, 1988); the mechanism may involve stimulation of opioid receptors (Hellstrom and Sjoqvist, 1988). Patients present with urge or overflow incontinence and typically have associated fecal incontinence as well. Disimpaction restores continence. These seven reversible causes of incontinence should be assiduously sought in every elderly patient. In one series of hospitalized elderly patients, when these causes were identified, continence was regained by most of those who became incontinent in the context of acute illness (Resnick, 1988). Regardless of their frequency, their identification is important in all settings because they are easily treatable and contribute to morbidity beyond incontinence. Key Points: Transient Incontinence Detrusor overactivity (DO) is the most common type of lower urinary tract dysfunction in incontinent elderly of either sex (Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1989). DO has been associated with increased spontaneous activity of detrusor smooth muscle and with specific changes at the cellular level. Termed the “complete dysjunction pattern,” these changes include widening of the intercellular space, reduction of normal (intermediate) muscle cell junctions, and emergence of novel “protrusion” junctions and “ultraclose abutments” connecting cells together in chains. These junctions and abutments may mediate a change in cell coupling from a mechanical to an electrical mechanism, which could facilitate propagation of heightened smooth muscle activity and provide the “final common pathway” by which such spontaneous cellular contractions result in involuntary contraction of the entire bladder (Elbadawi et al, 1993c, 1997a, 1997b; Hailemariam et al, 1997; Tse et al, 2000). However, this remains speculative to date. Other potential mechanisms are also being investigated, including, among others, the role of ischemia (Azadzoi et al, 2007), suburothelial myofibroblasts (Fry et al, 2007), and changes in central nervous system (CNS) structural and functional control mechanisms (Griffiths et al, 2007, 2009; Poggesi et al, 2008; Tadic et al, 2008; Kuchel et al, 2009). A distinction is generally made between detrusor overactivity that is associated with a CNS lesion and that which is not. In older patients, the distinction is often unclear, because involuntary detrusor contractions may be due to normal aging, a past stroke (even if clinically unapparent), or urethral incompetence or obstruction—even in a patient with Alzheimer disease. There is still no reliable way to determine the source of such contractions (Elbadawi et al, 2003). This obviously complicates treatment decisions. It also suggests that DO coexisting with urethral obstruction or stress incontinence is less likely to resolve postoperatively than in younger individuals without other reasons for detrusor overactivity (Resnick, 1988; Gormley et al, 1993). Traditionally, detrusor overactivity has been thought to be the primary urinary tract cause of incontinence in demented patients. Although this is true, DO is also the most common cause in nondemented older patients; the three studies that examined it failed to find an association between cognitive status and DO (Castleden et al, 1981; Resnick et al, 1989; Dennis et al, 1991). This lack of association likely reflects the fact that, in the elderly, there are multiple causes of DO unrelated to dementia, including cervical disk disease or spondylosis, Parkinson disease, stroke, subclinical urethral obstruction or sphincter incompetence, and age itself. Moreover, demented patients also may be incontinent due to the transient causes discussed above. Thus it is no longer tenable to ascribe incontinence in demented individuals a priori to detrusor overactivity (Resnick, 1995). Detrusor overactivity in the elderly exists as two physiologic subsets: one in which contractile function is preserved and one in which it is impaired (Resnick and Yalla, 1987; Yalla et al, 2007). The latter condition is termed detrusor hyperactivity with impaired contractility (DHIC) and is likely the most common form of DO in the elderly (Resnick et al, 1989; Elbadawi et al, 1993c). DHIC appears to represent the coexistence of DO and bladder weakness rather than a separate entity (Elbadawi et al, 1993c). Regardless of the cause, DHIC has several implications. First, because the bladder is weak, urinary retention develops commonly in these patients, and DHIC must be added to outlet obstruction and detrusor underactivity as a cause of retention. Second, even in the absence of retention, DHIC mimics virtually every other lower urinary tract cause of incontinence. For instance, if the involuntary detrusor contraction is triggered by or occurs coincident with a stress maneuver, and the weak contraction (often only 2 to 6 cm water) is not detected, DHIC will be misdiagnosed as stress incontinence or urethral instability (Resnick et al, 1996a); alternatively, because DHIC may be associated with urinary urgency, frequency, weak flow rate, elevated residual urine, and bladder trabeculation, in men it may mimic urethral obstruction (Resnick et al, 1996a). Third, bladder weakness often frustrates anticholinergic therapy of DHIC because urinary retention is induced so easily. Thus alternative therapeutic approaches are often required (see Therapy section). Stress incontinence is the second most common cause of incontinence in older women. As in younger women, it is usually associated with urethral hypermobility. A less common cause is intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) or type 3 stress incontinence (McGuire, 1981; Blaivas and Olsson, 1988). The prevalence of ISD may be lower than thought, however, because the diagnosis is often based solely on documenting a very low leak point or urethral closure pressure. Because urethral pressure decreases with age, even a closure pressure of less than 20 cm water does not establish the presence of ISD. Moreover, because urethral pressure normally decreases with detrusor contraction, leakage coinciding with low urethral pressure can be observed in patients with DHIC in whom the low pressure contraction is missed (Resnick et al, 1996a). A rare cause of stress incontinence in older women is “urethral instability,” in which the sphincter paradoxically relaxes in the absence of apparent detrusor contraction (McGuire, 1978). However, most older women thought to have this condition actually have DHIC (Resnick et al, 1996a). Incontinence in the setting of outlet obstruction is the second most common cause of incontinence in older men, although most obstructed men are not incontinent. When obstruction is associated with incontinence, it generally presents as urge incontinence owing to the associated DO; overflow incontinence owing to obstruction is uncommon. Especially in older adults, it is difficult to determine whether DO that occurs with obstruction is related to the obstruction or is simply coexistent owing to its increased prevalence with age, even in non-obstructed individuals. Nonetheless, DO is more common among obstructed patients, even older ones, (Resnick et al, 1995) and can cause incontinence. In most women, urethral elasticity decreases with age. In a small proportion of older women, this reduced elasticity may be compounded by fibrotic changes associated with atrophic vaginitis and can result in moderate urethral stenosis. Frank outlet obstruction, however, is as rare in older women as in younger women. When present, it is usually due to kinking associated with a large cystocele or to obstruction following bladder neck suspension. Rarely, bladder neck obstruction or a bladder calculus is the cause. Detrusor underactivity is usually idiopathic, but more information on this condition is emerging (Taylor and Kuchel, 2006). In the absence of obstruction or overt neuropathy, detrusor underactivity is characterized at the cellular level by widespread degenerative changes of both muscle cells and axons, without accompanying regenerative changes (Elbadawi et al, 1993b; Hindley et al, 2002). When it causes incontinence, detrusor underactivity is associated with overflow incontinence (<10% of geriatric incontinence) (Diokno et al, 1988; Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1989). Owing to the age-related decline in sphincter strength, however, the postvoid residual (PVR) volume in women with overflow incontinence is often lower than in younger women. A mild degree of bladder weakness occurs quite commonly in older individuals. Although insufficient to cause incontinence, it can complicate treatment of other causes (see Therapy section). “Functional” incontinence is often cited as a distinct type of geriatric incontinence and attributed to deficits of cognition and mobility. This concept is problematic for several reasons (Resnick and Marcantonio, 1997). First, “functional incontinence” implies that urinary tract function is normal, but studies of both institutionalized and ambulatory elderly reveal that normal urinary tract function is the exception even in continent subjects, and is rarely observed in the incontinent elderly (Ouslander et al, 1986; Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1989; Resnick et al, 1995). Second, incontinence is not inevitable with either dementia or immobility. We found that 17% of the most severely demented institutionalized residents (mean age 89) were continent and, if they could merely transfer from a bed to a chair, nearly half were continent (Resnick et al, 1988). Third, because functionally-impaired individuals are the most likely to suffer from factors causing transient incontinence (Resnick et al, 1988; DuBeau and Resnick, 1995; Skelly and Flint, 1995; Brandeis et al, 1997), a diagnosis of functional incontinence may result in failure to detect reversible causes of incontinence. Finally, functionally-impaired individuals may still have obstruction or stress incontinence and benefit from targeted therapy (Resnick, 1988; Resnick et al, 1989; Gormley et al, 1993; DuBeau and Resnick, 1995). Nonetheless, the importance of functional impairment as a factor contributing to incontinence should not be underestimated, because incontinence is also affected by environmental demands, mentation, mobility, manual dexterity, medical factors, and motivation (Jenkins and Fultz, 2005; Cigolle et al, 2007; Kikuchi et al, 2007) Although lower urinary tract function is rarely normal in such individuals, these factors are important to keep in mind because small improvements in each may markedly ameliorate both incontinence and functional status. In fact, once one has excluded causes of transient incontinence and serious underlying lesions, addressing causes of functional impairment may obviate the need for further investigation. Key Points: Established Incontinence In addition to the assessment outlined in Chapter 64, evaluation of the older patient should search for transient causes of incontinence (including nonprescribed medications) and functional impairment. It should be augmented by medical records, as well as input from caregivers. Functional assessment focuses on both basic activities of daily living (ADLs: i.e., transferring from a bed, walking, bathing, toileting, eating, and dressing) and more advanced “instrumental” activities of daily living (IADLs: i.e., shopping, cooking, driving, managing finances, using the telephone). The assessment is accomplished by using a questionnaire, which can be completed by the patient or caregiver prior to the evaluation, and by objective evaluation of the patient from the beginning of the encounter, noting affect, mobility, ability to sit and rise from a chair, ability to provide a coherent history, and amount of time and assistance required to dress and undress. Of course, as for younger individuals, it also is important to characterize the voiding pattern and the type of incontinence. Although the clinical type of incontinence most often associated with detrusor overactivity (DO) is urge incontinence, “urge” is neither a sensitive nor specific symptom; it is absent in 20% of older patients with detrusor overactivity, and the figure is higher in demented patients (Resnick et al, 1989). “Urge” is also reported commonly by patients with stress incontinence, outlet obstruction, and overflow incontinence. A better term for the symptom associated with DO is “precipitancy,” which can be defined in two ways. For patients with no warning of imminent urination (“reflex” or “unconscious” incontinence), the abrupt gush of urine in the absence of a stress maneuver can be termed precipitant leakage, and it is almost invariably due to DO. For those who do sense a warning, it is of less value to focus on the leakage, because the presence and volume of leakage in this situation depend on bladder volume, amount of warning, toilet accessibility, the patient’s mobility, and whether the patient can overcome the relative sphincter relaxation accompanying detrusor contraction (Dyro and Yalla, 1986). Instead, precipitancy should be defined as the abrupt sensation that urination is imminent, whatever the interval or amount of leakage that follows; defined in these two ways, precipitancy is both a sensitive and specific symptom (Resnick, 1990). Similar to the situation for urgency, other symptoms ascribed to DO also can be misleading in the older person unless explored carefully. Urinary frequency (greater than seven diurnal voids) is common (Brocklehurst et al, 1968; Diokno et al, 1986; Resnick, 1988), and may be due to voiding habit, preemptive urination to avoid leakage, overflow incontinence, sensory urgency, a stable but poorly compliant bladder, excessive urine production, depression, anxiety, or social reasons (Resnick, 1990). Conversely, incontinent individuals may severely restrict their fluid intake so that even in the presence of DO they do not void frequently. Thus the significance of urinary frequency, or its absence, can be determined only in the context of more information. Nocturia also can be misleading unless it is first defined (e.g., two episodes may be normal for the individual who sleeps 10 hours but not for one who sleeps 4 hours) and then approached systematically (Table 76–3). The three general reasons for nocturia—excessive urine output, sleep-related difficulties, and urinary tract dysfunction—can be differentiated by careful questioning and a voiding diary that includes voided volumes (Fig. 76–3). The record of voided volumes is inspected to determine the available bladder capacity (the largest single voided volume) and then compares this capacity to the volume of each nighttime void. For instance, if the available bladder capacity is 400 mL and each of three nightly voids is approximately 400 mL, the nocturia is due to excessive production of urine at night. If the volume of most nightly voids is much smaller than bladder capacity, nocturia reflects either: (1) a sleep-related problem (the patient voids because she is awake anyway), or (2) a problem with the lower urinary tract. Similar to excess urine output, sleep-related nocturia may also be due to treatable causes, including age-related sleep disorders, pain (e.g., bursitis, arthritis), dyspnea, depression, caffeine, or a short-acting hypnotic (e.g., triazolam). Bladder-related causes of nocturia are displayed in the table. Whatever the cause, the nocturnal component of incontinence can generally be ameliorated. COX-2, cyclooxygenase; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Adapted from Resnick NM. Noninvasive diagnosis of the patient with complex incontinence. Gerontology 1990;36(Suppl. 2):8–18. (Adapted from DuBeau CE, Resnick NM. Evaluation of the causes and severity of geriatric incontinence: a critical appraisal. Urol Clin North Am 1991;18:243–56.) The symptoms of “prostatism” also warrant comment. Owing to the high prevalence of medication use, nocturnal polyuria (Reynard et al, 1998), constipation, and DHIC, as well as the impairment of bladder contractility that accompanies aging, “prostatic” symptoms are even less specific in older men than in younger men (DuBeau and Resnick, 1991). Finally, patients or their caregivers should be asked which voiding symptom is most bothersome. For example, although a woman may have both stress and urge incontinence, the urge component may be her worst problem and should become the focus of evaluation and treatment. A man with “prostatism” may be most bothered by nocturia (DuBeau et al, 1995), which may be remedied without any consideration of his prostate (see Fig. 76–3). Failure to address symptom bother can lead to frustration for patient and provider alike. One of the most helpful components of the history is the voiding diary. Kept by the patient or caregiver for 48 to 72 hours, the diary records the time of each void and incontinent episode. No attempt is made to alter voiding pattern or fluid intake. Many formats have been proposed; a sample is shown in Figure 76–3. Similar to the history, the physical examination is essential to detect transient causes, comorbid disease, and functional impairment. In addition to the standard neurourologic examination, one should check for signs of neurologic diseases that are more common in older people, such as delirium, dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, cord compression, and neuropathy (autonomic or peripheral), as well as for atrophic vaginitis and general medical illnesses, such as heart failure and peripheral edema. The rectal exam checks for fecal impaction, masses, sacral reflexes, symmetry of the gluteal creases, and prostate consistency and nodularity; as noted in Chapter 92, the palpated size of the prostate is unhelpful. Many neurologically unimpaired elderly patients are unable to volitionally contract the anal sphincter, but, if they can, it is evidence against a spinal cord lesion. The absence of the anal wink is not necessarily pathologic in the elderly, nor does its presence exclude an underactive detrusor (due to diabetic neuropathy, for example).

The Impact of Age on Incontinence

Causes of Transient Incontinence

CAUSE

NOTES

Delirium/confusional state

Results from almost any underlying illness or medication; incontinence is secondary and abates once the cause of confusion has been corrected

Infection—Urinary (only symptomatic)

Causes incontinence, but the more common asymptomatic bacteriuria does not

Atrophic urethritis/vaginitis

Characterized by vaginal erosions, telangiectasia, petechiae, and friability; may cause or contribute to incontinence. Now controversial but may be worth a 3- to 6-month trial of estrogen, especially topical application (if not contraindicated by breast or uterine cancer)

Pharmaceuticals

Includes many prescribed and nonprescribed agents, because incontinence can be caused by diverse mechanisms (see Table 76–2)

Excess urine output

Results from large fluid intake, diuretic agents (including theophylline, caffeinated beverages, and alcohol), and metabolic disorders (e.g., hyperglycemia or hypercalcemia); nocturnal incontinence also may result from mobilization of peripheral edema (e.g., congestive heart failure [CHF], venous insufficiency, drug side effect)

Restricted mobility

Often results from overlooked, correctable conditions such as arthritis, pain, foot problem, postprandial hypotension, or fear of falling

Stool impaction

May cause both fecal and urinary incontinence that remit with disimpaction

TYPE OF MEDICATION

EXAMPLES

POTENTIAL EFFECTS ON CONTINENCE

Sedatives/hypnotics

Long-acting benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, flurazepam)

Sedation, delirium, immobility

Alcohol

Polyuria, frequency, urgency, sedation, delirium, immobility

Anticholinergics

Dicyclomine, disopyramide, antihistamines (sedating ones only, e.g., Benadryl)

Urinary retention, overflow incontinence, delirium, impaction

Antipsychotics

Thioridazine, haloperidol

Anticholinergic actions, sedation, rigidity, immobility

Antidepressants (tricyclics)

Amitriptyline, desipramine; not SSRIs

Anticholinergic actions, sedation

Anti-Parkinsonians

Trihexyphenidyl, benztropine mesylate (not L-dopa or selegiline)

Anticholinergic actions, sedation

Narcotic analgesics

Opiates

Urinary retention, fecal impaction, sedation, delirium

α-Adrenergic antagonists

Prazosin, terazosin, doxazosin

Urethral relaxation may precipitate stress incontinence in women

α-Adrenergic agonists

Nasal decongestants

Urinary retention in men

Calcium channel blockers

All dihydropyridines*

Urinary retention; nocturnal diuresis due to fluid retention

Potent diuretics

Furosemide, bumetanide (not thiazides)

Polyuria, frequency, urgency

NSAIDs

Indomethacin, COX-2 inhibitors

Nocturnal diuresis due to fluid retention

Thiazolidinediones

Rosiglitazone, pioglitazone

Nocturnal diuresis due to fluid retention

Anticonvulsants/analgesics

Gabapentin, pregabalin

Nocturnal diuresis due to fluid retention

Parkinson agents (some)

Pramipexole, ropinirole, amantadine

Nocturnal diuresis due to fluid retention

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

Captopril, enalapril, lisinopril

Drug-induced cough can precipitate stress incontinence in women and in some men with prior prostatectomy

Vincristine

Urinary retention owing to neuropathy

Established Incontinence

Lower Urinary Tract Causes

Causes Unrelated to the Lower Urinary Tract (“Functional” Incontinence)

Diagnostic Approach

Evaluation

History

Volume Related

Sleep Related

Lower Urinary Tract–Related

Voiding Diary

Targeted Physical Examination

Geriatric Incontinence and Voiding Dysfunction

• In the elderly, continence generally results not from normal lower urinary tract (LUT) function but despite abnormal LUT function. Thus the compensatory role of factors beyond the urinary tract is more important in older incontinent patients than in younger individuals.

• Established causes of geriatric incontinence comprise those in the lower urinary tract and also those beyond it.