ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS

ESSENTIAL CONCEPTS

Pregnancy can exacerbate many chronic gastrointestinal disorders; the central goal of evaluation is to control symptoms and rule out an urgent need for surgery while minimizing exposure to excessive tests and medications.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients should be in remission while trying to conceive, and most IBD medications are safe in pregnancy.

Appendicitis is the most common indication for surgery during pregnancy.

Indications for urgent surgery are the same in pregnant as in nonpregnant patients.

Incidence of gallstone-related disease is increased in pregnancy.

Efforts should be made to minimize risk to mother and fetus when performing diagnostic endoscopic and radiologic tests.

The management of gastrointestinal disease during pregnancy poses multiple challenges. First, gastrointestinal diseases are common during pregnancy, and many predisposing gastrointestinal disorders are aggravated by pregnancy. Second, diagnostic options are often limited in pregnancy as there is a need to minimize testing out of concern for both maternal and fetal exposure. Finally, the management of these diseases is more complex due to the need to consider additional risks to both the pregnant mother and the fetus incurred by medications, endoscopic procedures, and surgeries. Data on safety and efficacy of both medications and procedures during pregnancy are often scarce or inadequate; few controlled trials have included pregnant women, and fewer still were designed specifically to study gastrointestinal disease in this population. Table 7–1 summarizes the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) categories for medication use in pregnancy.

| FDA Pregnancy Category | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| A | Controlled studies in animals and women have shown no risk in the first trimester, and possible fetal harm is remote |

| B | Either animal studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women, or animal studies have shown an adverse effect that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester |

| C | No controlled studies in humans have been performed, and animal studies have shown adverse events, or studies in humans and animals are not available; should be given if potential benefit outweighs the risk |

| D | Positive evidence of fetal risk is available, but the benefits may outweigh the risk if life-threatening or serious disease |

| X | Studies in animals or humans show fetal abnormalities; drug contraindicated |

[PubMed: 16391963]

[PubMed: 16105538]

[PubMed: 12635416]

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Heartburn symptoms attributed to gastroesophageal reflux occur in nearly two-thirds of pregnancies and in women with no preexisting gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), often resolve following delivery. Symptoms are more common and more severe during the third trimester. Risk factors for heartburn during pregnancy include a history of heartburn before pregnancy or during previous pregnancies, multiparity, and younger maternal age. Reduced lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and decreased gastric and small bowel motility, possibly mediated by progesterone and to a lesser extent by estrogen, and increased abdominal pressure secondary to the gravid uterus are all implicated in the pathogenesis.

Heartburn is the predominant symptom of GERD, and regurgitation may accompany it. Symptoms are exacerbated by reclining and eating, and patients may also report hoarseness, cough, and asthma-like symptoms. Diagnosis is based on symptoms. Esophageal manometry and pH studies are rarely needed, and barium studies should be avoided in pregnancy. If required for severe symptoms, esophagogastro-duodenoscopy (EGD) can be performed during pregnancy with careful monitoring (see later discussion on endoscopy during pregnancy).

Lifestyle modification should be the first line of therapy. This includes avoidance of alcohol, caffeine, mint, chocolate, tobacco, and fatty and spicy foods. Avoiding late night meals and raising the head of the bed can also prevent nighttime symptoms.

Medications used in the treatment of GERD during pregnancy are listed in Table 7–2. Limited data are available about either the efficacy or the safety of antacids; however, aluminum- and calcium-containing antacids are considered acceptable in normal therapeutic doses during pregnancy, and limited studies have not shown evidence of teratogenicity in animals. Calcium-based antacids are considered the first line of pharmacologic therapy. All magnesium-containing compounds should be avoided during the last few weeks of pregnancy, as magnesium can slow or arrest labor and may cause convulsions. Antacids containing alginic acid or magnesium trisilicate should be avoided, as these chemicals have been associated with nephrolithiasis, hypotonia, respiratory distress, and cardiovascular impairment. Antacids containing sodium bicarbonate should not be used because they can cause maternal or fetal metabolic acidosis and fluid overload. Finally, antacids should be taken separately from iron preparations as they can interfere with absorption of iron.

| Drug | FDA Pregnancy Category | Recommendations for Pregnancy | Recommendations for Breast-Feeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antacids | |||

| Aluminum containing | None | Most low risk: minimal absorption | Low risk |

| Calcium containing | None | Most low risk: minimal absorption | Low risk |

| Magnesium containing | None | Most low risk: minimal absorption | Low risk |

| Magnesium trisilicates | None | Avoid long-term or high doses | Low risk |

| Sodium bicarbonate | None | Not safe: alkalosis | Low risk |

| Mucosal Protectants | |||

| Sucralfate | B | Low risk | No human data: probably compatible |

| H2-Receptor Antagonists | |||

| Cimetidine | B | Controlled data: low risk | Compatible |

| Famotidine | B | Paucity of safety data | Limited human data: probably compatible |

| Nizatidine | B | Limited human data: low risk in animals | Limited human data: probably compatible |

| Ranitidine | B | Low risk | Limited human data: probably compatible |

| Proton Pump Inhibitors | |||

| Esomeprazole | B | Limited data: low risk | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Lansoprazole | B | Limited data: low risk | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Omeprazole | C | Embryonic and fetal toxicity reported, but large data sets suggest low risk | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Pantoprazole | B | Limited data: low risk | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Rabeprazole | B | Limited data: low risk | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Promotility Agents | |||

| Cisapride | C | Controlled study: low risk, limited availability | Limited human data: probably compatible |

| Metoclopramide | B | Low risk | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection | |||

| Amoxicillin | B | Low risk | Compatible |

| Bismuth | C | Not safe: teratogenicity | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Clarithromycin | C | Avoid in first trimester | No human data: probably compatible |

| Metronidazole | B | Low risk: avoid in first trimester | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Tetracycline | D | Not safe: teratogenicity | Compatible |

Overall, sucralfate, histamine-2 blockers (H2-blockers), and the majority of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been found to be safe in pregnancy even when used in the first trimester. Sucralfate, like antacids, is a nonabsorbable medication and has been studied in a randomized controlled trial in pregnancy and found to be effective in the treatment of heartburn and regurgitation without presenting any risk to the fetus of pregnant women with normal renal function. H2-receptor blockers are commonly used and considered safe in pregnancy. Ranitidine has demonstrated safety and efficacy and is probably the H2-blocker of choice. Cimetidine is also considered safe; however, some authorities recommend avoiding its use in pregnancy because of feminization seen in some animal and human studies. Fewer data are available for famotidine and nizatidine.

Although PPIs are more effective than H2-blockers for controlling symptoms of GERD and healing esophagitis, they are not as well studied in pregnancy. Some investigators suggest documenting failure with H2-blockers and considering upper endoscopy before empiric trial. Observational studies suggest omeprazole can be used safely during pregnancy; however, increased fetal toxicity in animal studies and some evidence of cardiac malformations in human studies have led to class C categorization by the FDA. Animal studies support the safety of lansoprazole and rabeprazole; pantoprazole and esomeprazole also appear to be safe based on animal data, although studies in humans are limited.

Antireflux surgery during pregnancy should be avoided and is often not necessary as symptoms resolve or improve with delivery. Metoclopramide can be used in very refractory cases and may help treat pregnancy-related bowel hypomotility, which is hypothesized to contribute to pregnancy-related reflux. It is used to treat pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting, and one study shows no association with fetal malformations. For patients who have already undergone antireflux surgery prior to pregnancy, these methods appear to be effective in controlling GERD symptoms during and after pregnancy, and pregnancy does not appear to affect long-term outcomes and failure rates of antireflux surgery.

For patients experiencing symptoms in the postpartum period, antacids and sucralfate are considered safe because of limited maternal absorption. All H2-blockers are excreted in breast milk; however, cimetidine, ranitidine, and famotidine are felt to be safe during breast-feeding. Nizatidine has been associated with growth retardation in one animal study.

[PubMed: 15219482]

[PubMed: 12635418]

NAUSEA & VOMITING

Almost 50% of women experience nausea and vomiting during early pregnancy and an additional 25% have nausea alone. In a prospective study of 160 pregnant women, 80% of the women reporting nausea stated that it lasted all day, suggesting that “morning sickness” may be a misnomer. The onset of nausea is within 4 weeks after the last menstrual period in most patients and typically peaks at 9 weeks of gestation. Sixty percent of cases resolve by the end of the first trimester, and 91% resolve by 20 weeks of gestation. The stimulus for nausea and vomiting is likely produced by the placenta. Nausea and vomiting are less common in older women, multiparous women, and smokers probably due to smaller placental volumes in these women. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy are associated with a decreased risk of miscarriage.

The clinical course of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy correlates closely with the level of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). It is theorized that hCG may stimulate estrogen production from the ovary; estrogen is known to increase nausea and vomiting. Women with twins or hydatidiform moles, who have higher hCG levels than do other pregnant women, are at a higher risk for these symptoms. Vitamin B deficiency may also contribute since the use of multivitamins containing vitamin B reduces the incidence of nausea and vomiting.

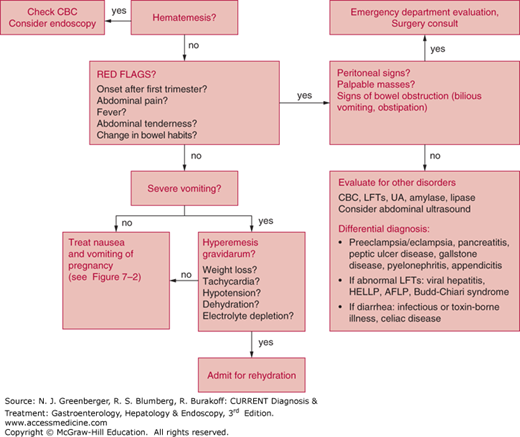

A careful evaluation to exclude other disorders and contributing factors is important (Figure 7–1). The presence of heartburn suggests the coexistence of GERD and should prompt treatment with antacid medications (see the earlier discussion of GERD). Although patients can experience soreness of the abdominal muscles and ribs in the setting of recurrent vomiting and retching, abdominal pain is not typically associated with nausea and vomiting during pregnancy.

Epigastric, periumbilical, or right-sided pain can suggest gallstone disease, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), pancreatitis, or appendicitis, and an appropriate workup should be performed to exclude these disorders. Vomitus typically contains recently ingested food or yellow juice. Bilious vomitus or severe periumbilical pain can suggest bowel obstruction.

The patient with uncomplicated pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting should have normal findings on physical examination. The presence of dehydration or orthostatic hypotension can suggest hyperemesis gravidarum (see later discussion). The presence of abdominal tenderness, rebound, palpable masses, abdominal distention, or a succussion splash should prompt laboratory evaluation and imaging to rule out other causes.

An elevated white blood cell count (beyond physiologic leukocytosis of pregnancy or accompanied by a neutrophilia) can suggest the presence of cholecystitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, or pyelonephritis. A urine specimen for urinalysis and urine culture to exclude urinary tract infection should be obtained. Other relevant testing includes thyroid function testing, liver blood tests (chronic hepatitis C infection can be associated with a high incidence of nausea), hepatitis serologies, and fasting glucose level. Severely abnormal serum electrolytes resulting from vomiting suggest the diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum.

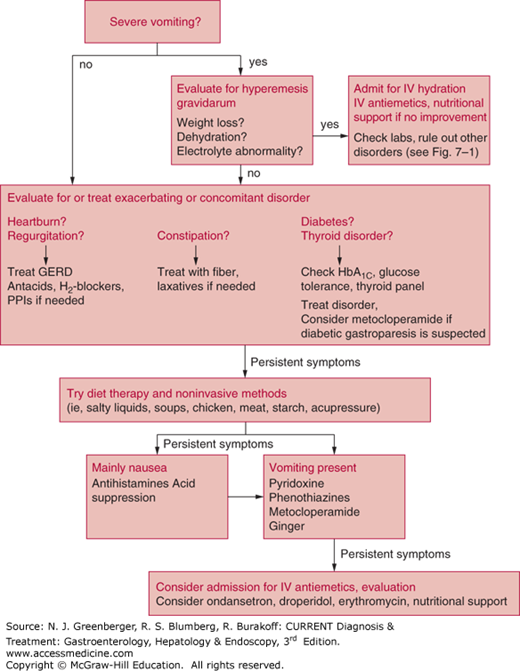

The medical and nonmedical literature is replete with dietary suggestions for women suffering from this problem. Medical treatment is directed toward control of symptoms (Figure 7–2).

Women should avoid exposure to odors, foods, or supplements that appear to trigger nausea. Typically, fatty foods are avoided because these can delay gastric emptying. Small, frequent meals of bland carbohydrates (starches such as noodles, potatoes, and rice), chicken, and fish are recommended. For patients with severe nausea and vomiting, small sips of salty liquids such as sports beverages or broth are recommended. Juices and creamy or dairy beverages are not advised as these can exacerbate symptoms. Some authors also recommend avoidance of vegetables or high-fiber foods, which can form bezoars. Acupressure is often performed with the use of wrist bands (Seabands) worn continuously for a period of a few days, followed by a hiatus of few days; it is noninvasive, and many women report a reduction in the number of episodes of nausea, although data are equivocal about whether this benefit is actual or partially a placebo effect. Most studies did not show a significant benefit in the treatment of severe vomiting. A recent Cochran review supports the use of pyridoxine (B6) for control of nausea symptoms, and another small trial comparing 1.05 g of ginger daily for 3 weeks with 75 mg of pyridoxine found a similar modest benefit in reducing symptoms of nausea.

Women who have persistent nausea and vomiting and high concentrations of ketones require intravenous hydration with multivitamins, including thiamine, with follow-up measurement of levels of urinary ketones and electrolytes. Antiemetic agents should be prescribed in these patients.

Antihistamines such as meclizine have been used with no reports of teratogenicity. Studies of dimenhydrinate and diphenhydramine during pregnancy have shown conflicting results on safety and efficacy. Phenothiazines such as promethazine, prochlorperazine, and trimethobenzamide are considered low-risk drugs based on studies in pregnant women and also have clinical efficacy in this setting. Metoclopramide is used frequently in Europe for this indication, and one study shows no association with fetal malformations. In a recent randomized trial, intravenous metoclopramide and intravenous promethazine had similar efficacy in the treatment of hyperemesis, but metoclopramide caused less drowsiness and dizziness. An Israeli cohort study involving 3458 women who were exposed to metoclopramide in the first trimester (in most cases for 1–2 weeks) showed no significant association between exposure and the risk of congenital malformations, low birth weight, preterm delivery, or perinatal death.

In April 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration approved doxylamine succinate 10 mg/pyridoxine hydrochloride 10 mg (Diclegis) as the first medication to specifically treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in more than 30 years. It has proven efficacy in randomized, placebo-controlled trials and should be considered a first-line drug.

Other prokinetics such as domperidone (used in Canada), bethanechol, and erythromycin have not been studied. Ondansetron is considered low risk in pregnancy, although its use is typically limited to cases of hyperemesis gravidarum. Granisetron and dolasetron have not been studied in human pregnancies.

[PubMed: 14583914]

[PubMed: 12635417]

[PubMed: 20843504]

[PubMed: 19516033]

[PubMed: 15051552]

[PubMed: 20410771]

HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

This condition is characterized by severe vomiting with concurrent dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, or weight loss. The reported incidence is 0.3–1% of pregnancies, and symptoms nearly always begin in the first trimester, although hyperemesis can sometimes be indicated by vomiting that persists after the first trimester. This condition is characterized by persistent vomiting, weight loss of more than 5%, ketonuria, electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia), and dehydration (high urine specific gravity). Hyperemesis gravidarum is associated with high estrogen levels and is more likely to occur with multiple gestations, gestational trophoblastic disease, and fetal abnormalities such as triploidy, trisomy 21, and hydrops fetalis. It has also been associated with hyperthyroidism, preeclampsia, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets), and acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP). Although overall, patients with hyperemesis have good fetal outcomes, one study found that patients who experience a loss of 5% or more of body weight have a greater risk of growth retardation or fetal anomalies.

Patients may report dry mouth, sialorrhea, hyperolfaction, dysgeusia (altered or metallic taste), and decreased taste sensation. Physical examination may reveal signs of dehydration, including dry mucous membranes and poor skin turgor. The presence of epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, headache, and diplopia can suggest preeclampsia or eclampsia. Blood pressure should be measured and urinalysis performed; hypertension and proteinuria support the diagnosis of preeclampsia. Hyperreflexia and edema may also be present in preeclampsia, and the development of seizures defines eclampsia.

Blood chemistries should be evaluated as hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and hyponatremia are common. Complete blood count and liver blood tests should also be checked to evaluate for HELLP syndrome (elevated transaminases without significant elevation of alkaline phosphatase or bilirubin, often with low platelets). AFLP can present with fulminant hepatic failure (elevated prothrombin time, jaundice, and elevated transaminases) and sometimes concurrent renal failure and hypoglycemia. These patients must be transferred to an intensive care unit, and a hepatologist should be consulted immediately. HELLP syndrome and AFLP typically occur late in pregnancy, usually in the third trimester. Other diseases associated with severe vomiting include hepatic vein thrombosis or Budd-Chiari syndrome, which can be diagnosed with a Doppler ultrasound. Celiac sprue can be diagnosed by tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A (IgA) and antiendomysial IgA or endoscopy, or both. Helicobacter pylori can be diagnosed by serology, endoscopy, or hydrogen breath test. Hyperemesis does not typically cause elevation in liver blood tests or renal failure unless severe dehydration is present.

Pregnancies of women with hyperemesis gravidarum can be complicated by low birth weight if the mother has experienced weight loss; however, fetal fatality is rare. Severe vomiting can rarely cause Mallory-Weiss tears or esophageal rupture. Rarely, women can develop peripheral neuropathies due to vitamin B6 and B12 deficiencies. The most serious complication is Wernicke encephalopathy resulting from thiamine deficiency. Poor dietary intake can also result in deficiency of other vitamins and nutrients such as iron, calcium, and folate. Infants of mothers who have lost weight in early pregnancy, as compared with infants of women whose weight increased or stayed the same, have lower mean birth weights and lower percentile weights for gestational age.

Oral and intravenous hydration and repletion of electrolytes is the primary treatment. Thiamine should be administered prior to dextrose to avoid Wernicke encephalopathy. After 24 hours of aggressive intravenous hydration, the infusion should be adjusted to maintain urine output. Once oral hydration is tolerated, broth or salty liquids should be started, followed by small carbohydrate meals such as crackers and noodles. In some cases, nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding may be required. In rare cases, parenteral nutrition has been used, but this should be avoided if possible due to risks of infection, diabetes, cholelithiasis, and risks associated with central line placement. Four cases have been reported of placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes with jejunal extensions for this indication, during which fetal monitoring and anesthesia support were provided. Although procedure-related adverse fetal outcomes were not reported, this procedure should be reserved for patients at high nutritional risk, after nasoenteric feeding has failed and parenteral nutrition is contraindicated (hyperglycemia, hypercoagulability, or inadequate venous access). Medications used to control nausea and vomiting are often effective for hyperemesis. One study demonstrated some benefit of powdered root of ginger (20 mg orally, four times daily) in controlling symptoms. A few case reports describe benefits of erythromycin in controlling hyperemesis. Another study showed some efficacy of methylprednisolone, but steroids can be associated with adverse fetal outcomes. A recent study showed that ondansetron and metoclopramide demonstrated similar antiemetic and antinauseant effects but the overall profile, particularly regarding adverse effects, was better with ondansetron.

[PubMed: 24807340]

[PubMed: 15316422]

CONSTIPATION

New-onset constipation and exacerbation of chronic constipation are common complaints during pregnancy. Several physiologic changes are believed to contribute to this problem, including poor fluid intake in the setting of nausea and vomiting, iron supplementation, bed rest or decreased exercise, and hormonal changes such as increased progesterone and estrogen, which is thought to depress the migrating motor complex and slow orocecal transit time.

In uncomplicated constipation, the physical examination should be normal. Fever, abdominal pain, tenderness, distention, nausea or vomiting, or obstipation should prompt evaluation for other causes such as bowel obstruction or volvulus.

The treatment of constipation during pregnancy is similar to its treatment in nonpregnant patients. First-line therapy consists of dietary fiber, which is the safest and most physiologic way to treat constipation; however, many patients will not respond to dietary fiber alone.

Psyllium, calcium polycarbophil, and methylcellulose are bulk laxatives that can be used as an alternative or adjunct to dietary fiber. These agents should be diluted and taken with food during meals. Fiber increases fecal water content, increases stool weight, decreases colonic transit time, and improves stool consistency. The laxative effect may be delayed for days. Pregnant patients should be warned that fiber can cause bloating and flatulence and instructed to consume sufficient fluids with it. Docusate, a stool softener, can be used alongside fiber supplements and is used routinely in pregnancy; however, there is one case report of neonatal hypomagnesemia associated with maternal oral administration of sodium docusate.

Osmotic laxatives can be used if fiber supplementation fails. Sorbitol and lactulose are poorly absorbed sugars that stimulate fluid accumulation in the colon by an osmotic effect. Lactulose is more expensive and should not be used in diabetic patients because it contains galactose. In addition, it can exacerbate nausea in pregnant patients with this symptom. Polyethylene glycol has been used to treat chronic constipation during pregnancy and causes less abdominal bloating and flatulence than other osmotic laxatives. It is now available over-the-counter and is recommended by many obstetric societies.

Stimulant laxatives are generally reserved for patients who do not respond to fiber or osmotic laxatives. If used chronically, electrolytes should be monitored as hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hyponatremia, and dehydration can result. Senna is generally safe in pregnancy and can be used in combination with bulk laxatives. It can be used at bedtime with fluids up to three times per week. Cascara is milder and is less often associated with abdominal discomfort. Bisacodyl is also safe in pregnancy as tablets or suppository, but can produce some abdominal discomfort when administered orally.

Fecal impaction should be treated with digital disimpaction. Mineral oil, tap water, or retention enemas can be used to soften stool. Bisacodyl suppository can then be used along with oral agents to treat constipation.

Agents to avoid during pregnancy include castor oil, which can initiate premature uterine contractions; aloe, which has been associated with congenital malformations; and saline hyperosmotic agents such as magnesium laxatives and phosphosoda, which can promote sodium and water retention. Orally administered mineral oil should also be avoided because it prevents absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Lubiprostone and linaclotide are class C and should not be used during pregnancy.

[PubMed: 12635420]

DIARRHEA

Acute or chronic diarrhea can occur in pregnant women, and it is believed that pathogenesis and differential diagnosis are similar in pregnant and nonpregnant patients. Most cases of acute diarrhea are caused by viral infections such as rotavirus and Norwalk virus and are associated with large-volume, watery diarrhea that is self-limited. Bacterial illness often produces more frequent stools of small volume, abdominal pain, occasional fever, and blood and leukocytes in the stool.

Evaluation of diarrhea is typically warranted only if diarrhea is profuse, leads to dehydration, is bloody, is associated with high fevers, or if the illness persists for 48 hours without improvement or becomes chronic. Noninfectious causes of acute and chronic diarrhea include functional diarrhea, food intolerance, use of sugar substitutes such as sorbitol and mannitol, and IBD. A careful dietary and family history should be obtained.

Stool cultures for bacterial pathogens, ova, and parasites, and toxin or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for Clostridium difficile are the next step in evaluation. Flexible sigmoidoscopy with biopsy is considered safe in pregnancy and can be performed if needed to evaluate bloody or persistent diarrhea.

Uncomplicated diarrhea should be treated with oral rehydration using juices, noncaffeinated beverages, and broth. Orange juice and bananas provide potassium, and salted crackers and broth can provide sodium. Small, frequent meals and avoidance of high-fat food, caffeine, dairy, and artificial sweeteners are recommended.

Antibiotics should be used only in the setting of documented infection with bacterial or parasitic microbes. Albendazole is teratogenic in animals, but in the setting of helminthic infections during pregnancy, the benefit is felt to be greater than the theoretical risk. Metronidazole can be used for C difficile, Giardia lamblia, and Entamoeba histolytica, but should be avoided during the first trimester and should not be administered long term because there are no data supporting its use for more than 2–3 weeks at a time. Ampicillin and erythromycin stearate have been used for bacterial causes of diarrhea, the latter specifically for Campylobacter jejuni infection. Less data are available on vancomycin, but it is also considered a low-risk drug. Azithromycin is not associated with congenital defects but may cause maternal gastrointestinal discomfort during pregnancy. Second-generation cephalosporins such as cefuroxime and cefixime can be used for acute shigellosis. Fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin estolate, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole should not be used based on current data available. Rifaximin is a nonabsorbable antibiotic with a wide spectrum of gram-negative and anaerobic coverage that is currently FDA approved for traveler’s diarrhea. Although it should eventually be useful during pregnancy, no data are currently available regarding its use in pregnant women.

Antidiarrheal agents can be used to control symptoms in severe or persistent disease once active infection has been excluded. Kaolin and pectin are not absorbed and are probably safe although impairment of iron absorption is a possibility. Loperamide in small doses has been used in and is rated category B during pregnancy. Codeine can also be used in small amounts. Agents to avoid include bismuth subsalicylate (contained in Kaopectate), mainly because of the teratogenicity of salicylates. Diphenoxylate with atropine has also been found to be teratogenic. Alosetron should be avoided as well, because there are few data on its use during pregnancy. Cholestyramine has been used to treat cholestasis of pregnancy safely; however, its use can result in fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies including coagulopathy, which can lead to neonatal intracerebral hemorrhage.

HEMORRHOIDS

Hemorrhoids are common in the US adult population and often become symptomatic or worsen during pregnancy. Pregnancy-associated constipation, poor venous return, increase in circulating blood volume, and extended time in the sitting position are all believed to contribute to this problem.

The perianal area should be inspected to rule out other contributions to pain and pruritus such as pinworms, fissures, fistulas, or ulcers. Other causes of rectal bleeding should be evaluated for, and a flexible sigmoidoscopy performed if needed. Internal hemorrhoids should be graded: first-degree hemorrhoids bleed but do not prolapse and can be visualized by anoscopy; second-degree hemorrhoids protrude during defecation or with straining but revert when straining stops; third-degree hemorrhoids are continuously prolapsed but easily reduced; fourth-degree hemorrhoids cannot be reduced.

External hemorrhoids require treatment if they become thrombosed, which often results in pain or discomfort with sitting. If conservative measures such as stool softeners, daily warm sitz baths, and mild analgesics are not effective, surgical excision under local anesthesia is safe during pregnancy and does not affect the fetus. Clot incision and removal is generally only a temporizing measure as thrombosis usually recurs.

Internal hemorrhoids can cause bleeding, pain, or pruritus that may require treatment. Treatment of constipation is essential. Topical therapies such as witch hazel, hydrocortisone cream, and topical anesthetics (eg, benzocaine, dibucaine, or pramoxine) can help treat pruritus. Products containing epinephrine or phenylephrine should be avoided, especially in women with hypertension, diabetes, or fluid overload. If topical measures fail, band ligation for first-, second-, or third-degree internal hemorrhoids or injection sclerotherapy for first- or second-degree hemorrhoids is safe in pregnancy. Band ligation carries the associated risk of acute necrotizing perianal sepsis; however, this complication is rare.

Infrared photocoagulation or laser coagulation of first- and second-degree hemorrhoids is also minimally invasive, although safety in pregnancy has not been demonstrated. For patients who fail office-based procedures or those with fourth-degree lesions, closed excisional hemorrhoidectomy using local anesthesia has been reported to be safe and effective in pregnancy.

[PubMed: 12635420]

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME

The symptom complex and defining criteria of irritable bowel syndrome is described in Chapter 24. Irritable bowel syndrome is common in pregnancy, partly because it is a common syndrome in women of childbearing age and partly because pregnancy seems to exacerbate gastrointestinal symptoms associated with the syndrome. Many women experience an increase in constipation, or conversely, an increase in stool frequency. Abdominal pain, bloating, flatulence, and nausea are also exacerbated by pregnancy, it is thought because of the impact of female hormones on gastrointestinal motility.

In patients with preexisting irritable bowel syndrome, evaluation mainly consists of ruling out other causes of constipation, irregular stools, and abdominal discomfort. Failure to respond to medical management or alarm symptoms such as bleeding, weight loss, or fever should prompt a search for other causes. In patients who present with irritable bowel syndrome during pregnancy, the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome is suggested by the combination of pain, flatulence, irregular defecation, and mucus in stools, and the exacerbation of symptoms by eating and relief by defecation. (See Chapter 24.)

Dietary measures are the safest way to treat irritable bowel syndrome in pregnancy. Fiber supplementation can be implemented for constipation-predominant, diarrhea-predominant, and alternating irritable bowel syndrome. Patients can add bran to each meal or purchase supplements such as psyllium. Patients should be warned that an increase in bloating and flatulence occurs initially with fiber but may improve with time.

Medications used in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome are outlined in Table 7–3. For patients with constipation-predominant symptoms who do not respond to bulk laxatives, osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol, sorbitol, or lactulose can be used and are considered low risk in pregnancy. Tap-water enemas can be used to treat fecal impaction. Magnesium citrate and sodium phosphate should be avoided. For a full discussion of laxatives that can be used in pregnancy, see the earlier discussion of constipation. For patients with diarrhea-predominant symptoms, a low-fat, nondairy diet should be tried first. After this, loperamide or codeine can be used in small doses after infection is ruled out. For information about antidiarrheal agents for use during pregnancy, see the earlier section on treatment of diarrhea in pregnancy.

| Drug | FDA Pregnancy Category | Recommendations for Pregnancy | Recommendations for Breast-Feeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alosetron | B | Avoid: restricted access | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Amitriptyline | C | Avoid: no malformations, but worse outcomes | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Bisacodyl | C | Low risk in short-term use | Safety unknown |

| Bismuth subsalicylate | C | Not safe: teratogenicity | No human data: potential toxicity |

| Castor oil | X | Uterine contraction and rupture | Possibly unsafe |

| Cholestyramine | C | Low risk, but can lead to infant coagulopathy | Compatible |

| Desipramine | C | Avoid: no malformations, but worse outcomes | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Dicyclomine | B | Avoid: possible congenital anomalies | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Diphenoxylate/atropine | C | Teratogenic in animals: no human data | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Docusate | C | Low risk | Compatible |

| Hyoscyamine | C | No available data | No human data: probably compatible |

| Imipramine | D | Avoid: no malformations, but worse outcomes | Limited human data: potential toxicity |

| Kaopectate | C | Unsafe because now contains bismuth | No human data: probably compatible |

| Lactulose | B | No human studies | No human data: probably compatible |

| Loperamide | B | Low risk: possible increased cardiovascular defects | Limited human data: probably compatible |

| Lubiprostone | C | No human studies but pregnancy loss in guinea pigs | Avoid use |

| Magnesium citrate | B | Avoid long-term use: hypermagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, dehydration |