Diagnosis

Test

Treatment

Esophageal spasm

Upper GI

Hyoscyamine, lorazepam

Cardiospasm

Upper Gi

Hyoscyamine, lorazepam

Stasis esophagitis

Endoscopy

PPI

Regurgitant esophagitis

Endoscopy

Dietary counseling

Esophageal ulcer

Endoscopy

PPI

Gastritis

Endoscopy

PPI

Stenosis

Upper GI

Endoscopic dilation

Pylorospasm

Upper GI

Endoscopic Botox injection

Gastroparesis

Upper GI, history

Endoscopic Botox injection

Improper alimentation

Negative upper GI and endoscopy

Dietary counseling

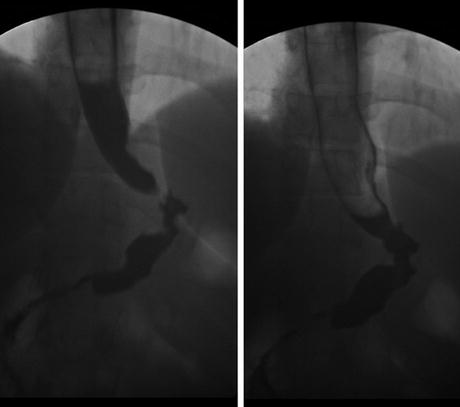

Fig. 13.1

Sleeve gastrectomy patient 3 weeks postoperative with chest tightness and poor oral intake. First image (left) reveals a narrow area in the proximal stomach. After a second drink of barium, the narrow area (image on right) opens up consistent with a spasm. Treatment was hyoscyamine three times a day. Symptoms resolved in 5 days

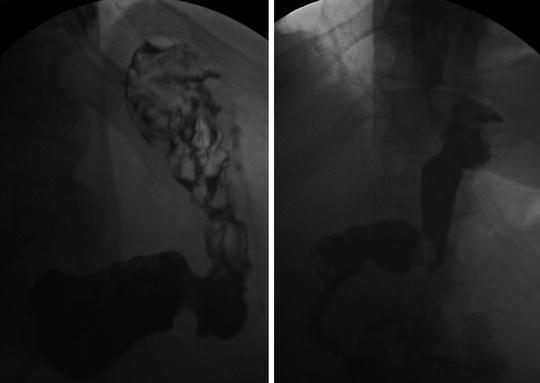

Fig. 13.2

Sleeve gastrectomy patient 30 days postoperative and cannot advance to soft foods without vomiting. He had diabetes for more than 5 years. The upper GI on the left reveals a lack of gastric emptying. He underwent an endoscopy which was negative. Botox® was injected into the pylorus. His symptoms resolved and a follow-up upper GI (right ) revealed prompt gastric emptying

Once objective studies have been completed and anatomical obstructions have been ruled out, another round of education with the patient is necessary to get them through this period of food intolerance. Patients may need to maintain a liquid diet for more than 2 weeks. Any patient who is vomiting frequently or cannot tolerate their vitamins may need to be admitted and supported with IV fluids, multivitamin, thiamine, and folate. This should be rare provided that the abovementioned diagnostic and therapeutic maneuvers have been done.

13.7 Stenosis and Volvulus

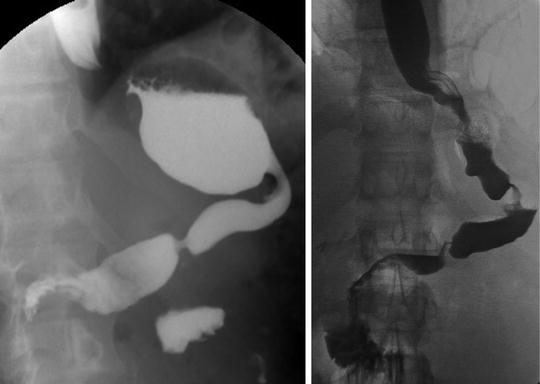

Symptoms of stenosis include regurgitation, progressive dysphagia, and even sialorrhea (drooling). Any patient who reports difficulty with liquids or worsening dysphagia should be evaluated before they get to the point of constant vomiting and drooling. As stated earlier, the upper GI and endoscopy are the diagnostic and therapeutic methods most appropriate for any sleeve patient presenting with a possible stenosis. Figure 13.3 is an excellent example of a patient who did not have signs of immediate obstruction but over a year developed worsening reflux and vomiting problems due to both a retained fundus and a relative narrowing at the angularis. The upper GI easily made the diagnosis.

Fig. 13.3

Patient 2 years post-sleeve gastrectomy with chronic vomiting, reflux, and aspiration symptoms. Endoscope passed easily through the region of the angularis and pylorus. Preoperative upper GI (image on left ) reveals a large retained fundus with relative narrowing at the angularis. Laparoscopic resection of the retained fundus resolved the obstructive symptoms (postoperative image on right )

The reported incidence of stenosis ranges from 0.1 to 3.9 % [24, 25]. Patients usually present with vomiting and obstructive symptoms in the first few weeks after surgery but can present as late as 27 months after surgery [25]. True stenosis with a fixed narrowing is more likely to present early after surgery. Functional stenosis due to torsion or prolapse at the angularis may present early or even a year or more after surgery as a progressive vomiting syndrome.

Burgos et al. [24] reported on 5 patients with gastric stenosis (all at the angularis) in a series of 717 patients. Treatment with single-balloon dilation was successful in one and with rigid Savary dilators in three others. One patient was converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass after two Savary dilator attempts. While the occurrence of stenosis was only 0.69 %, the authors did note that in two of the five patients, the staple line was oversewn.

Ogra and Kini [25] reported 26 of 857 sleeve patients with stenosis (3.03 %). Three of the 26 had proximal gastric stenosis that responded well to a 20 mm balloon dilation. The other 23 patients had narrowing at the angularis and only 7 of those responded to balloon dilation. The nine patients with stenosis at the angularis that failed balloon dilation went on to additional procedures. Six underwent dilation with an achalasia balloon to 30 mm and three underwent placement of a self-expanding metal stent . Seven patients underwent achalasia balloon dilation first and only two of these needed to go on to stenting. The endoscope passed through all of these “stenosis” sites prior to dilation suggesting that the primary problem was torsion or prolapse at a relatively narrow angularis. The surgical description did not mention an omentopexy.

Vilallong and Himpens [26] reported on the laparoscopic management of persistent strictures after sleeve gastrectomy. Sixteen of 812 patients required surgical treatment. Endoscopic treatment was not attempted because the endoscope passed through the entire sleeve and the stenosis was deemed “functional.” This was a complex group of patients, many with prior operations. The reason for treatment included dysphagia in all 16 patients plus, reflux in 8 patients, cachexia in 1, and eructation in 1. Seromyotomy was performed in 14 of the patients but had a leak rate of 35.7 %. Two patients underwent a wedge resection with a good result and three were converted to a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree