Courtenay Kathryn Moore, MD

Urologists are well versed in the diagnosis and treatment of male sexual dysfunction. However, what is less commonly recognized but demonstrated in several studies is that male erectile dysfunction negatively impacts female sexual function and sexual quality of life (Fisher et al, 2005; Rosen et al, 2007). It was not until recently that urologists actually began to consider female sexual function as relevant to their practice. Based on the National Health and Social Life Survey, sexual dysfunction is actually more prevalent in women (43%) than in men (31%). Other studies suggest female sexual dysfunction (FSD) affects 25% to 76% of women in the United States. In one study, 98% women seeking routine gynecologic care had sexual concerns (Nusbaum et al, 2000).

Despite the high prevalence of sexual problems among women, physicians and patients alike are hesitant to initiate conversations about female sexual health. In a study of 471 physicians, only 22% stated they always screen for FSD whereas 55% screen most of the time and 23% never or rarely screen their patients (Pauls et al, 2005). Physicians cited various reasons for their lack of screening for FSD, the most common being lack of time. The majority of respondents (69%) underestimated the prevalence of FSD in their patient population. Fifty percent believed that their training and ability to treat FSD was unsatisfactory. Bachmann (2006) conducted a similar survey among physicians and health care providers attending the annual meetings of four specialty societies. Of the 1946 participants 42% did not inquire about FSD, citing limitations in time and training, embarrassment, and the absence of effective treatments as obstacles to discussing FSD. Sixty percent of participants rated both their knowledge and comfort level with FSD as fair or poor, whereas 86% rated treatment options as fair or poor.

Female Sexual Anatomy and Physiology

Genital Anatomy

The labia majora are two large, longitudinal, cutaneous folds of adipose and fibrous tissue that extend from the mons pubis to the posterior fourchette. The skin of the outer convex surface of the labia majora is pigmented and covered with hair follicles. The inner surface does not have hair follicles but has many sebaceous glands. Histologically the labia majora have both sweat and sebaceous glands. The labia majora are homologous to the scrotum in the male. The labia minora, which are homologous to the penile urethra, are two smaller folds located between the labia majora and the vaginal orifice. Anteriorly they divide at the clitoris to form the prepuce superiorly and the frenulum of the clitoris inferiorly. Histologically they are composed of dense connective tissue with erectile tissue and elastic fibers rather than adipose tissue. The skin of the labia minora is less cornified and has many sebaceous glands but no hair follicles or sweat glands (Katz et al, 2007). The labia minora surround a space called the vestibule, into which the orifices of the urethra, vagina, and Bartholin glands open.

Skene glands, or paraurethral glands, are tubular glands adjacent to the distal urethra. Skene ducts run parallel to the long axis of the urethra for approximately 1 cm before opening into the distal urethra (Katz et al, 2007). Skene glands are homologous to the prostate in the male.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System

The female sexual response is mediated primarily via spinal cord reflexes that are under descending control from the brainstem. The nucleus paragigantocellaris, which projects directly to the pelvic efferent neurons and interneurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord, is believed to play a role in female orgasm (Meston, 2000; Meston and Frohlich, 2000). The pelvic efferent neurons and interneurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord contain the neurotransmitter serotonin (Walsh et al, 2002). Serotonin applied to the spinal cord inhibits spinal sexual reflexes and may explain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-induced anorgasmia (Meston, 2000). The raphe nuclei and pallidus, the magnus and parapyramidal region, and the locus ceruleus all project to the lumbosacral spinal cord and are believed to play a role in sexual function with the periaqueductal gray area acting as a relay center for sexual stimuli (Meston, 2000; Meston and Frohlich, 2000).

In males the hypothalamic medial preoptic area, which has widespread connections to the limbic system and brainstem, functions in the ability to recognize a sexual partner. In female animals, lesions to this area increase not only lordosis but also avoidance (Meston, 2000). During orgasm and arousal oxytocin is released from neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

More recently functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have been used to identify specific patterns of brain activation in the female sexual response. A study by Park and coworkers (2001) reported significant activation of the inferior frontal lobe, cingulate gyrus, insula, hypothalamus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, and inferior temporal lobe in women watching erotic films. In another study Jeong and associates (2005) compared brain activation in premenopausal and postmenopausal women watching erotic videos. Premenopausal women were found to have greater activity in whole brain and limbic, temporal, and parietal lobes whereas postmenopausal had greater activation in the superior frontal gyrus. A study by Arnow and associates (2009) compared functional MR images after erotic videos in women with and without a history of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and reported significantly greater activity in the entorhinal cortex in women with no history of sexual dysfunction and higher activation in the medial frontal gyrus and putamen in women with HSDD. These findings suggest that women with HSDD have a shift in attentional focus from erotic cues to a self-monitoring of sexual response and performance concerns, underscoring the neural correlates of heightened self-focus that clinically characterizes women with HSDD (Arnow et al, 2009).

Endocrine Factors

Estrogen and Progesterone

Traditionally three sex steroids have been implicated in female sexual behavior: estrogens, progestins, and androgens. In premenopausal woman, with normal ovulation, estrogen and progesterone levels are maintained until menopause. In premenopausal women the primary source of estradiol production is from the ovaries, under the control of follicle-stimulating hormone and inhibin produced by the pituitary gland, with less contributed from the adrenal gland and ovarian androgen precursors (Simpson, 2000; Davis et al, 2004; Giraldi et al, 2004). During the late follicular phase and in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle there is a rise in estradiol. During the luteal phase there is also a rise in progesterone. Estradiol and progesterone levels fall abruptly at the time of menopause when ovulation ceases (Simpson, 2000; Davis et al, 2004; Giraldi et al, 2004).

Recent research suggests that estrogen and progesterone have little direct influence on female desire. Schreiner-Engel and coworkers (1989) found no significant difference in the estrogen levels of women with and without clinically diagnosed HSDD. Numerous studies have also shown no change in sexual desire with the administration of exogenous estrogen therapy alone in women (Furuhjelm et al, 1984; Nathorst-Boos et al, 1993a, 1993b). However, administration of both estrogen and androgen in natural and surgically menopausal woman has been shown to restore normal levels of sexual desire (Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985a). Although lack of estrogen may not directly impair female arousal and desire, it can indirectly impair sexual function by decreasing vasocongestion and lubrication and vaginal epithelial atrophy. Because estrogen plays a role in the regulation of vaginal and nitric oxide synthase expression, both naturally and surgically induced menopause result in decreased vaginal and nitric oxide synthase expression, resulting in apoptosis of the vaginal wall, smooth muscle, and epithelium. Treatment with estrogen therapy increases nitric oxide synthase expression, restores vaginal lubrication, and decreases dyspareunia, resulting in improved female sexual satisfaction.

In general, progestins do not have a direct impact on female sexual function. Although oral contraceptives that increase progesterone levels have been associated with decreased sexual desire and interest, treatment with progesterone alone has not been shown to improve sexual desire in either premenopausal or menopausal women (Persky, 1976; Schreiner-Engel et al, 1981; Leiblum et al, 1983; Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985b). Indirectly, progesterone may affect female sexual behavior by increasing depressive moods. It is believed that progesterone and estradiol compete for receptors in the central nervous system, and higher ratios of progesterone to estradiol correlate with unpleasant feelings and depressive moods (Persky et al, 1982).

Testosterone

Premenopausal women also produce 0.3 mg of testosterone daily. Unlike in men, 50% of testosterone production in women comes directly from the ovaries and the adrenal glands, with the remaining 50% produced by testosterone precursors such as androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in peripheral tissues (Walsh et al, 2002). Only 2% of the total testosterone is free, whereas 98% is bound to albumin or sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG). Fluctuations in SHBG alter the bioavailability of free testosterone. The administration of exogenous estrogens, such as oral contraceptives, increases hepatically synthesized SHBG, thereby reducing the bioavailability of free testosterone. Oral contraceptives also diminish follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels, thereby suppressing ovulation and inhibiting androgen production. The combination of these two mechanisms may lead to very low circulating levels of free and bioavailable testosterone. Several studies have documented the negative effects of oral contraceptives on sexual function, including diminished sexual interest and arousal, suppression of female-initiated sexual activity, and decreased frequency of sexual intercourse and sexual enjoyment (Basson et al, 2004; Davis et al, 2004; Nappi et al, 2005). In premenopausal women with regular menstrual cycles, testosterone and androstenedione rise in the late follicular and luteal phases (Vierhapper et al, 1997). In premenopausal women there is also a diurnal variation in testosterone, with levels peaking in the morning (Vierhapper et al, 1997).

Unlike estrogen and progesterone levels, which fall abruptly with menopause, testosterone levels diminish gradually throughout life. Between the ages of 30 and 60, total and free testosterone levels decrease by 50% (Basson, 2008). In addition, adrenal precursors, DHEA and DHEA sulfate, decrease with increasing age (Baulieu, 1996; Baulieu et al, 2000). Decreased androgen levels associated with aging have been associated with decreased libido, arousal, orgasm, and genital sensations.

In studies of both naturally and surgically menopausal women the administration of testosterone alone, without estrogen replacement therapy, has been shown to improve desire, arousal, and sexual fantasies (Leiblum et al, 1983; McCoy and Davidson, 1985; Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985a). However, the effect of relationship between testosterone levels and desire in premenopausal women is less well defined. Several studies have failed to find differences in testosterone levels in premenopausal women with and without HSDD (Stuart et al, 1987; Schreiner-Engel et al, 1989). New data suggest that testosterone is beneficial in premenopausal women with HSDD who have low circulating testosterone levels (Schwenkhagen and Studd, 2009). Women placed on testosterone supplementation must be counseled regarding the potential risks and side effects of therapy, which include acne, hirsutism, male pattern baldness, clitoral hypertrophy, and increased triglyceride levels.

Physiology of Female Sexual Response Cycle

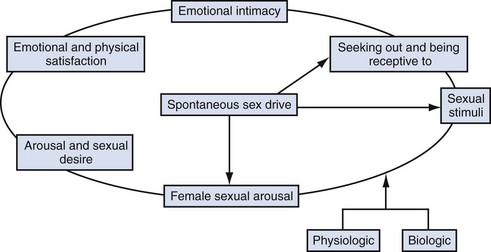

In response to much criticism, Basson, in 2000, described a more contemporary nonlinear model of female sexual response, integrating emotional intimacy, sexual stimuli, and relationship satisfaction (Fig. 30–1). This model recognizes that female sexual functioning is more complex and is less linear than male sexual functioning. It also emphasizes that many women initially begin a sexual encounter from a point of sexual neutrality, with the decision to be sexual stemming from the conscious need for emotional closeness or as a result of seduction from a partner. As demonstrated by the model, arousal stems from intimacy and seduction and often precedes desire. This model emphasizes that women have many reasons for engaging in sexual activity other than spontaneous sexual drive. Sexual neutrality or being receptive to, rather than initiating sexual activity, is considered a normal variation of female sexual functioning.

Classification and Epidemiology

Unlike male erectile dysfunction, female sexual disorders are more difficult to assess, diagnose, and treat. One of the initial barriers in the field of FSD was the lack of consensus of the definitions and criteria of these disorders. In 1998 the American Foundation of Urologic Disease Consensus convened to create a classification system and common terminology. It was at this conference that FSD was divided into four categories: sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and sexual pain disorders. In 2000 the panel reconvened and changed the classification schema to add “causing personal distress” as a criterion for diagnosis (Basson et al, 2000). This distinction is important because many studies on the prevalence of FSD have not qualified if the sexual symptoms reported caused “personal distress.” In 2004 the Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine, consisting of over 200 multidisciplinary experts from 60 countries, convened and revised the definitions for FSD (Table 30–1).

Table 30–1 Revised Definitions for Female Sexual Dysfunction from the Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine

Estimates on the prevalence of FSD varies greatly depending on the definitions, the assessment tool used, and the demographics of the population (age, race, educational and marital status). Hayes and colleagues (2008) compared the difference in the prevalence of the types of FSD among 356 women using four different instruments and found that the prevalence varied substantially depending on the instrument used, leading to the conclusion that the instrument chosen to assess for FSD significantly affects prevalence estimates. U.S. population census data suggest that roughly 10 million American women aged 50 to 74 years self report complaints of diminished lubrication, pain during intercourse, decreased arousal, and difficulty achieving orgasm (Salonia et al, 2004).

Several studies have shown that the prevalence of FSD varies depending on age, with women older than age 45 years at an increased risk of having FSD (Shifren et al, 2008). Among women aged 40 and older, the most common reported sexual problem was low desire (38.7% to 54%), difficulty with lubrication (21.5% to 39%), and inability to orgasm (20.5% to 34%) (Shifren et al, 2008).

Female pelvic floor disorders (incontinence, lower urinary tract symptoms, and pelvic organ prolapse) have also been shown to have a negative impact on female sexual function. Women with incontinence are up to three times more likely to experience decreased arousal, infrequent orgasms, and increased dyspareunia (Handa et al, 2004; Hansen, 2004; Laumann et al, 1999; Salonia et al, 2004). Several recent large studies have found a statistically significant improvement in sexual function scores among women who underwent successful surgery for incontinence and prolapse (Brubaker et al, 2009; Handa et al, 2007).

Key Points

Physiology

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing FSD is to identify women with the problem. Plouffe (1985) and colleagues found three simple questions as effective at identifying sexual problems as a lengthy interview (Kammerer-Doak and Rogers, 2008).

Validated questionnaires are also valuable tools to help identify the presence or absence of a sexual problem. A list of questionnaires recommended by the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence for evaluation of sexual function and health in women with urinary symptoms by grade is shown in Table 30–2. For additional information regarding commonly used and validated sexual function assessment tools the reader is referred to the Baylor College of Medicine website (http://femalesexualdysfunctiononline.org/resources/) (Kingsberg and Janata, 2007).