This article reviews the evaluation and management of patients with suspected extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease, such as asthma, chronic cough, and laryngitis, which are commonly encountered in gastroenterology practices. Otolaryngologists and gastroenterologists commonly disagree upon the underlying cause for complaints in patients with one of the suspected extraesophageal reflux syndromes. The accuracy of diagnostic tests (laryngoscopy, endoscopy, and pH- or pH-impedance monitoring) for patients with suspected extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease is suboptimal. An empiric trial of proton pump inhibitors in patients without alarm features can help some patients, but the response to therapy is variable.

Key points

- •

Suspected extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease, such as asthma, chronic cough, and laryngitis, are commonly encountered in gastroenterology practices.

- •

Otolaryngologists and gastroenterologists commonly disagree with the underlying cause for the complaints in patients with one of the suspected extraesophageal reflux syndromes.

- •

The accuracy of diagnostic tests (laryngoscopy, endoscopy, and pH- or pH-impedance monitoring) for patients with suspected extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease is suboptimal.

- •

An empiric trial of proton pump inhibitors in patients without alarm features can help some patients, but the response to therapy can be quite variable.

- •

Esophageal reflux testing with pH- or pH-impedance monitoring should be reserved for patients with an inadequate response to empiric therapy.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) affects approximately 40% of the US population. Typical GERD symptoms include heartburn and acid regurgitation. However, extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as cough, hoarseness, and asthma, also occur. Over the last 2 decades, these entities, often called extraesophageal reflux (EER), have gained a lot of attention clinically and in the medical literature. The expense of managing patients with suspected EER has been estimated to cost over 5 times that of patients with typical GERD symptoms.

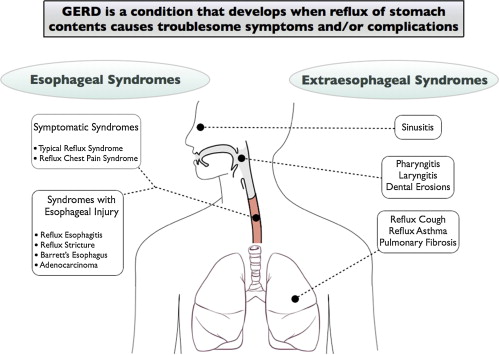

In 2006 the Global Consensus Group published the “Montreal Definition and Classification of GERD,” which was created via a modified Delphi process of worldwide experts. Within this report, the manifestations of GERD were divided into 2 major groups of syndromes, esophageal syndromes and extraesophageal syndromes . The esophageal syndromes were classified as symptomatic syndromes (typical reflux syndrome and reflux-chest pain syndrome) or syndromes with esophageal injury (reflux esophagitis, reflux stricture, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma). The extraesophageal syndromes were divided into those with established associations (reflux-cough, reflux-laryngitis [ Box 1 ], reflux-asthma, and reflux-dental erosion syndromes) and those with proposed associations (pharyngitis, sinusitis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and recurrent otitis media) ( Fig. 1 ).

- •

Hoarseness

- •

Dysphonia

- •

Sore or burning throat

- •

Excessive throat clearing

- •

Chronic cough

- •

Globus

- •

Apnea

- •

Laryngospasm

- •

Dysphagia

- •

Postnasal drip

- •

Laryngeal neoplasm

Four key principles regarding the extraesophageal syndromes with established associations were emphasized in this consensus classification :

- 1.

An association between GERD and the manifestations of these syndromes exists.

- 2.

These syndromes rarely occur in isolation without concomitant manifestations of the typical esophageal syndrome.

- 3.

These syndromes are usually multifactorial, with GERD as one of several potential aggravating factors.

- 4.

Data supporting a significant benefit of antireflux therapy for these syndromes are weak.

These principles should guide gastroenterologists in their understanding and management of extraesophageal syndromes. This article reviews the diagnostic and therapeutic data discussing EER and provides a framework of how a gastroenterologist may play a role in the management of patients referred for such problems.

Pathophysiology, or what might be going on?

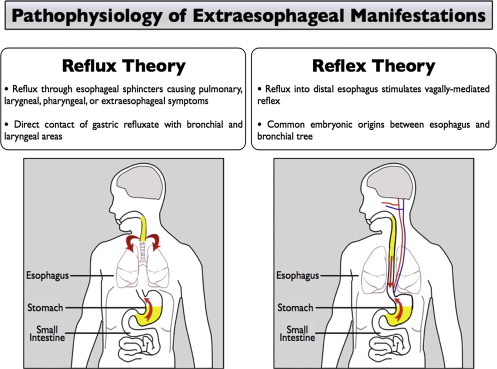

Two general pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed as the reasons for which GERD may cause EER ( Fig. 2 ). The first mechanism occurs by direct reflux injury to the oropharyngeal or tracheobronchial structures (the “reflux” theory). This mechanism assumes that gastroesophageal refluxate breaches the protective barrier provided by the upper esophageal sphincter. The refluxate subsequently reaches tissues that are more susceptible than the esophagus to acid-peptic injury, such as the larynx. The second mechanism occurs when reflux stimulates the vagus nerve, leading to cough, bronchoconstriction, or other extraesophageal symptoms (the “reflex” theory). Because both the esophagus and the tracheobronchial tree derive from the embryologic foregut, they share a common innervation. Stimuli in the distal esophagus can therefore lead to respiratory symptoms via vagally mediated reflexes.

Pathophysiology, or what might be going on?

Two general pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed as the reasons for which GERD may cause EER ( Fig. 2 ). The first mechanism occurs by direct reflux injury to the oropharyngeal or tracheobronchial structures (the “reflux” theory). This mechanism assumes that gastroesophageal refluxate breaches the protective barrier provided by the upper esophageal sphincter. The refluxate subsequently reaches tissues that are more susceptible than the esophagus to acid-peptic injury, such as the larynx. The second mechanism occurs when reflux stimulates the vagus nerve, leading to cough, bronchoconstriction, or other extraesophageal symptoms (the “reflex” theory). Because both the esophagus and the tracheobronchial tree derive from the embryologic foregut, they share a common innervation. Stimuli in the distal esophagus can therefore lead to respiratory symptoms via vagally mediated reflexes.

Diagnosis, or how might the association be established?

Patients with suspected EER are commonly referred to gastroenterologists from primary care, otolaryngologists, and pulmonologists, often without other manifestations of GERD. The responsibility of gastroenterologists is to help the patient and referring physician understand (1) the potential contribution of GERD to the symptoms, if indeed there is any, (2) the role of testing for GERD, and (3) the likelihood that antireflux therapy will help control the patient’s symptoms. However, patients often now present to gastroenterologists with the preconceived notion that GERD is the cause of their symptoms. These cases pose a much different issue for the consulting gastroenterologist, especially when the diagnosis has come from another specialist, such as an otolaryngologist who diagnosed reflux-laryngitis, often called laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR), based on the patient’s symptoms and laryngoscopic examination. Instead of providing consultation regarding the questions above, the gastroenterologist is then asked to manage or provide insight about the patient with “refractory” LPR.

Otolaryngologists often overdiagnose LPR as the cause of the laryngeal syndrome, which can lead patients and their referring physicians to anchor on this diagnosis as the underlying cause. Therefore, the first step in understanding the patient’s problems is to deconstruct the diagnosis into the presenting syndrome and review the diagnostic steps taken to come to such a diagnosis, the therapies provided to date, and the response to such therapies. Gastroenterologists also need to understand that they may be anchored in a preconceived notion that the patient does not have GERD. Therefore, instead of asking the question, “Does this patient have GERD?,” or more importantly, “If this patient has GERD, does it explain the patient’s presentation?,” an alternative question may be considered, “To what degree could GERD be contributing to this patient’s presentation?” A corollary to this question is, “How much could antireflux therapy help this patient?”

What is the Value of Laryngoscopy in Assessing Patients with Suspected EER?

The Reflux Finding Score is a scoring system that permits otolaryngologists to grade 8 findings at the time of laryngoscopy that are purported to be associated with LPR ( Table 1 ). These findings are subglottic edema, ventricular obliteration, erythema/hyperemia, vocal fold edema, diffuse laryngeal edema, posterior commissure hypertrophy, granuloma/granulation tissue, and excessive endolaryngeal mucus. However, the accuracy of laryngoscopy in the diagnosis of LPR is frequently called into question. Normal subjects without an underlying diagnosis of a laryngeal or voice disorder have a prevalence of abnormal laryngoscopic findings (at least one pathologic sign) in the range of 83% to 93%. Abnormalities have been found more commonly during flexible laryngoscopy, usually the technique used in routine otolaryngology practice, compared with rigid laryngoscopy in the same healthy volunteer. Such a high underlying prevalence of abnormal findings limits the specificity of the flexible laryngoscopic examination for diagnosing LPR. As the specificity decreases, the likelihood that a positive (abnormal) test truly represents the presence of the disease (ie, the positive predictive value) decreases. Furthermore, both inter- and intra-rater agreement of laryngoscopic findings are poor. With such variability in laryngoscopy, its utility in confirming the diagnosis of LPR as the cause of symptoms suggestive of EER is limited.

| Laryngoscopic Feature | Finding | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Subglottic edema | Absent | 0 |

| Present | 2 | |

| Ventricular obliteration | Absent | 0 |

| Partial | 2 | |

| Complete | 4 | |

| Erythema/hyperemia | Absent | 0 |

| Arytenoids only | 2 | |

| Diffuse | 4 | |

| Vocal fold edema | Absent | 0 |

| Mild | 1 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Severe | 3 | |

| Polypoid | 4 | |

| Diffuse laryngeal edema | Absent | 0 |

| Mild | 1 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Severe | 3 | |

| Obstructing | 4 | |

| Posterior commissure hypertrophy | Absent | 0 |

| Mild | 1 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Severe | 3 | |

| Obstructing | 4 | |

| Granuloma/granulation tissue | Absent | 0 |

| Present | 2 | |

| Thick endolaryngeal mucus | Absent | 0 |

| Present | 2 |

What is the Value of Endoscopy in Assessing Patients with Suspected EER?

Endoscopic evaluation can theoretically assist in the assessment of patients with suspected EER, as a finding of esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and/or other mucosal abnormalities could increase the likelihood that the symptoms are truly caused by GERD. However, such mucosal abnormalities are uncommonly found in patients with suspected EER. For example, in one study of 41 patients with LPR diagnosed by laryngoscopy, only 5% of patients (2/41) were found to have esophagitis while off proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy for at least 16 days, although 41.5% (17/41) had hiatal hernia. In another study of 32 patients with abnormal laryngoscopy suspected of having LPR, 10 patients (31%) had esophagitis, 8 of which were classified as Los Angeles (LA) grade A. Similarly, in 28 patients with abnormal laryngoscopy and pathologic findings on 24-hour pH monitoring, only 5 patients (18%) had esophagitis, 4 of which were classified as LA grade A (2 also had Barrett metaplasia). Among this group of 5 patients, heartburn was present in the 3 patients with Barrett esophagus or LA grade B esophagitis. On the other hand, in one retrospective study of 63 patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma, isolated LPR symptoms were more commonly documented in the record than isolated typical GER symptoms (30% vs 19%), leading the investigators to conclude that LPR symptoms could better predict the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. However, the predictive value of isolated LPR symptoms for the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has not been prospectively demonstrated. At present the yield of routine upper endoscopy in patients with isolated EER is low and seems to add little value to the patient without any typical reflux symptoms or other indication for upper endoscopy.

What is the Value of Esophageal Reflux Studies in Assessing Patients with Suspected EER?

The measurement of esophageal acid exposure by ambulatory pH monitoring has long been considered a major tool in the diagnosis of GERD. The degree of esophageal mucosal injury seems to correlate with increased accuracy of pH monitoring, with decreasing sensitivity and specificity estimates in patients without macroscopic esophageal mucosal injury. The recent introduction of multichannel intraluminal impedance (MII) in combination with pH monitoring (pH-MII) permits the detection of all types of refluxate, irrespective of its acidity. Despite its utility in assessing the presence of GERD in patients with typical reflux syndromes, the accuracy of pH- or pH-MII testing is much more variable in confirming the diagnosis of GERD in patients presenting with a possible EER syndrome.

In a systematic review of proximal esophageal and hypopharyngeal pH monitoring for investigating the diagnosis of reflux in patients with laryngitis, up to 43% of healthy controls were found to have abnormalities in pharyngeal acid exposure. This prevalence in normal subjects was not significantly different when compared with the prevalence of abnormal pharyngeal reflux in patients with laryngitis. One possibility is that nonacidic or weakly acidic reflux could explain the lack of difference between acid exposure on pH-only testing. This problem could be overcome by using pH-MII. In one study of 23 patients with presumed LPR who underwent pH-MII on high-dose PPI therapy, 52% of patients had significant nonacidic reflux and 22% had persistent breakthrough acid reflux. However pH-MII monitoring is not yet accepted by all investigators because the total number of reflux events detected by pH-MII does not seem to correlate with traditional esophageal physiologic parameters.

In asthma, abnormal esophageal acid exposure occurs in up to 82% of patients; however, many of these patients do not have any typical GERD symptoms. In a systematic review of the association between GERD and asthma, Havemann and colleagues found the prevalence of abnormal esophageal acid exposure in asthma patients recruited principally from asthma clinics ranged from 15% to 82%. Among asthma patients without typical symptoms of GERD, the prevalence of abnormal esophageal pH ranged from 10% to 50%.

The Dx-pH Measurement System (Respiratory Technology Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) is a new minimally invasive transnasal device that measures pH in the posterior oropharynx. This device is designed to be more sensitive to acid reflux events than traditional pH monitoring in patients with suspected LPR. However outcome studies will need to be performed to assess the utility of this device among this group of patients. Furthermore, increasing sensitivity for acid in the oropharynx may lead to more false positive results. In a study of 10 patients with chronic cough who underwent simultaneous evaluation with the Dx-pH device and pH-MII, 44% (17/39) of acid “reflux” events detected by the Dx-pH device were characterized as swallows by impedance, and 38% (15/39) of events were not associated with a reflux event on pH-MII recording.

Direct measurement of the association between symptoms and reflux events is another potential benefit of reflux monitoring. However the value of these measurements has recently been called into question. In a study by Kavitt and colleagues, investigators used an acoustic cough monitor to assess the accuracy of patient-reported cough symptoms during pH-MII testing. They found that patients significantly underreported their cough episodes. This inaccuracy suggests that using a patient-reported symptom association measure (ie, symptom index or symptom association probability) is not likely to reflect the true association between cough and specific reflux events. With underreporting of cough, these indices are more likely to be falsely negative. However, if a patient reports a cough at a time remote from an actual cough event, the indices could be falsely positive.

Treatment, or how well a therapeutic trial with antireflux therapy might help?

Reflux Cough Syndrome

A recent Cochrane meta-analysis that included 19 studies (13 in adults, 6 in children) concluded that there was insufficient evidence to confirm that PPI therapy is universally beneficial for reflux-related cough. In 9 studies comparing PPI to placebo, prolonged PPI therapy (2–3 months) did not show statistically significant improvement over placebo in resolution of cough (odds ratio 0.46; 95% CI 0.19–1.15). Two subsequent randomized controlled trials, both using twice-daily esomeprazole (either 20 mg/dose for 8 weeks or 40 mg/dose for 12 weeks ), have augmented the body of data refuting the utility of PPI therapy for patients with chronic cough. In the latter study, randomization was stratified based on the results of pH testing. Even within the subgroup of patients with abnormal pH testing (as defined by a DeMeester score >14.7), high-dose PPI therapy did not show statistically significant differences in the cough-related outcomes.

Over the last several years, chronic sensory neuropathic cough ( Box 2 ) has been used to describe an idiopathic chronic cough, often with a sensation of a tickle in the throat, neck, or sternal notch, and associated with one or more triggers. In sensory neuropathic cough, the pathogenesis of the cough is related to an abnormal intrinsic cough reflex as opposed to the specific aggravating factor such as GERD ( Fig. 3 ). Based on this model, medical therapy with neuromodulating medications (eg, gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline) directed at improving the abnormal reflex has been used. In one study of 18 patients referred to a specialty esophageal clinical with cough and suspected EER, low-dose gabapentin (100–900 mg/day; median 100 mg/day) significantly improved cough in 12 of 17 (71%) patients. The response to gabapentin did not depend on the results of the pH or pH-MII study. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin in 62 patients with refractory chronic cough, gabapentin significantly improved cough-specific quality of life compared with placebo (74% vs 46%; P = .038). In this study, the dose of gabapentin was increased from 300 mg to 1800 mg over a 6-day escalation period, unless their cough symptoms were eliminated or they developed intolerable side effects, and was maintained for a 10-week period. Patients had negative investigations for GERD or negative responses to trials of antireflux therapy, although the details of the evaluation for GERD were not specified. Side effects of gabapentin occurred in 10/32 (31%) patients compared with 10% among patients in the placebo group ( P = .059) and most commonly consisted of nausea, dizziness, and/or fatigue. Although these studies did not specifically address reflux-related cough, the premise that a neuromodulator can be effective in treating cough provides hope for patients referred to gastroenterologists for this particular problem.