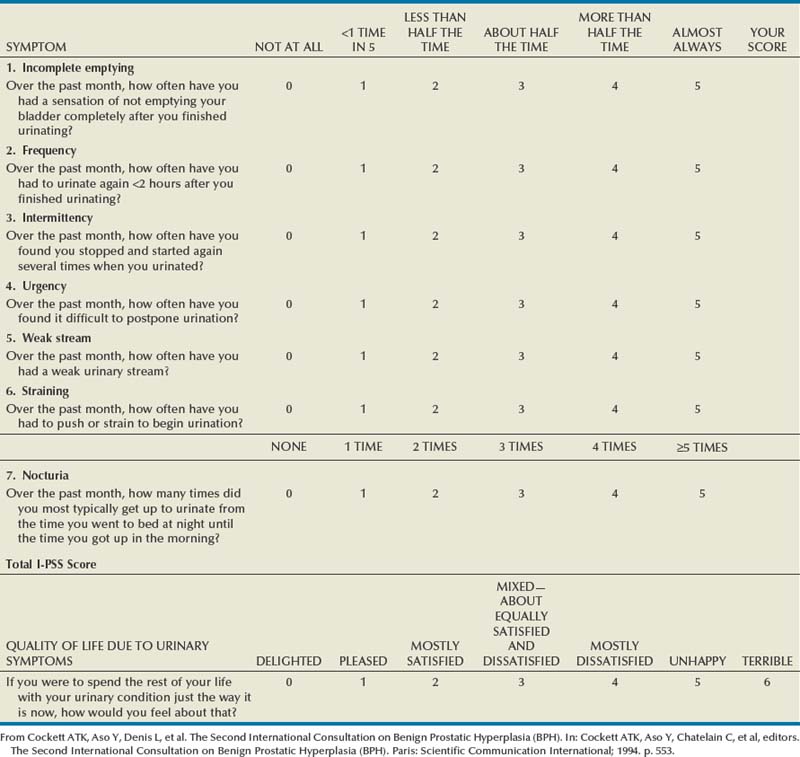

Glenn S. Gerber, MD, Charles B. Brendler, MD Nocturia is nocturnal frequency. Normally, adults arise no more than twice at night to void. As with frequency, nocturia may be secondary to increased urine output or decreased bladder capacity. Frequency during the day without nocturia is usually of psychogenic origin and related to anxiety. Nocturia without frequency may occur in the patient with congestive heart failure and peripheral edema in whom the intravascular volume and urine output increase when the patient is supine. Renal concentrating ability decreases with age; therefore urine production in the geriatric patient is increased at night, when renal blood flow is increased as a result of recumbency. In general, nocturia may be attributed to nocturnal polyuria (nocturnal urine overproduction) and/or diminished nocturnal bladder capacity (Weiss and Blaivas, 2000). Nocturia may also occur in people who drink large amounts of liquid in the evening, particularly caffeinated and alcoholic beverages, which have strong diuretic effects. In the absence of these factors, nocturia signifies a problem with bladder function secondary to urinary outlet obstruction and/or decreased bladder compliance. Postvoid dribbling refers to the terminal release of drops of urine at the end of micturition. This is secondary to a small amount of residual urine in either the bulbar or the prostatic urethra that is normally “milked back” into the bladder at the end of micturition (Stephenson and Farrar, 1977). In men with bladder outlet obstruction, this urine escapes into the bulbar urethra and leaks out at the end of micturition. Men will frequently attempt to avoid wetting their clothing by shaking the penis at the end of micturition. In fact, this is ineffective, and the problem is more readily solved by manual compression of the bulbar urethra in the perineum and blotting the urethral meatus with a tissue. Postvoid dribbling is often an early symptom of urethral obstruction related to BPH, but, in itself, seldom necessitates any further treatment. It is important for the urologist to distinguish irritative from obstructive lower urinary tract symptoms. This most frequently occurs in evaluating men with BPH. Although BPH is primarily obstructive, it produces changes in bladder compliance that result in increased irritative symptoms. In fact, men with BPH more commonly present with irritative than obstructive symptoms, and the most common presenting symptom is nocturia. The urologist must be careful not to attribute irritative symptoms to BPH unless there is documented evidence of obstruction. In general, lower urinary tract symptoms are nonspecific and may occur secondary to a wide variety of neurologic conditions, as well as to prostatic enlargement (Lepor and Machi, 1993). In this regard, two important examples are mentioned. Patients with high-grade flat carcinoma in situ of the bladder may present with urinary irritative symptoms. The urologist should be particularly aware of the diagnosis of carcinoma in situ in men who present with irritative symptoms, a history of cigarette smoking, and microscopic hematuria. In our personal experience, we cared for a 54-year-old man who presented with this history and was treated for BPH for 2 years before the diagnosis of bladder cancer was established. Once the correct diagnosis was made, the patient had developed muscle-invasive disease and required a cystectomy for cure. Since its introduction in 1992, the American Urological Association (AUA) symptom index has been widely used and validated as an important means of assessing men with lower urinary tract symptoms (Barry et al, 1992). The original AUA symptom score is based on the answers to seven questions concerning frequency, nocturia, weak urinary stream, hesitancy, intermittency, incomplete bladder emptying, and urgency. The International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS) includes these seven questions, as well as a global quality-of-life question (Table 3–1). The total symptom score ranges from 0 to 35 with scores of 0 to 7, 8 to 19, and 20 to 35 indicating mild, moderate, and severe lower urinary tract symptoms, respectively. The I-PSS is a helpful tool both in the clinical management of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and in research studies regarding the medical and surgical treatment of men with voiding dysfunction. The use of symptom indices has limitations, and it is important for the physician to discuss the patient’s responses with him. It has been demonstrated that a grade 6 reading level is necessary to understand the I-PSS, and some patients with neurologic disorders and dementia may also have difficulty completing the symptom score (MacDiarmid et al, 1998). In addition, the symptom score and obstructive and irritative voiding symptoms are nonspecific, and the symptoms may be caused by a variety of conditions other than BPH. Similar symptom scores have been demonstrated to be present in age-matched men and women between 55 and 79 years of age (Lepor and Machi, 1993). Despite these limitations, the I-PSS is a simple adjunct in assessing men with lower urinary tract symptoms and may be used in the initial evaluation of men with lower urinary tract symptoms, as well as in the assessment of treatment response. Enuresis refers to urinary incontinence that occurs during sleep. It occurs normally in children up to 3 years of age but persists in about 15% of children at age 5 and about 1% of children at age 15 (Forsythe and Redmond, 1974). Enuresis must be distinguished from continuous incontinence, which occurs in the day and night and which, in a young girl, usually indicates the presence of an ectopic ureter. All children older than age 6 years with enuresis should undergo a urologic evaluation, although the vast majority will be found to have no significant urologic abnormality. Men who complain of premature ejaculation should be questioned carefully because this is obviously a subjective symptom. It is common for men to ejaculate within 2 minutes after initiation of intercourse, and many men who complain of premature ejaculation in actuality have normal sexual function with abnormal sexual expectations. However, there are men with true premature ejaculation who reach orgasm within less than 1 minute after initiation of intercourse. This problem is almost always psychogenic and best treated by a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist who specializes in treatment of this problem and other psychologic aspects of male sexual dysfunction. With counseling and appropriate modifications in sexual technique, this problem can usually be overcome. Alternatively, treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as sertraline and fluoxetine has been demonstrated to be helpful in men with premature ejaculation (Murat Basar et al, 1999). There are obviously many diseases that may affect the GU system, and it is important to listen and record the patient’s previous medical illnesses. Patients with diabetes mellitus frequently develop autonomic dysfunction that may result in impaired urinary and sexual function. A previous history of tuberculosis may be important in a patient presenting with impaired renal function, ureteral obstruction, or chronic, unexplained UTIs. Patients with hypertension have an increased risk of sexual dysfunction because they are more likely to have peripheral vascular disease and because many of the medications that are used to treat hypertension frequently cause impotence. Patients with neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis are also more likely to develop urinary and sexual dysfunction. In fact, 5% of patients with previously undiagnosed multiple sclerosis present with urinary symptoms as the first manifestation of the disease (Blaivas and Kaplan, 1988). As mentioned earlier, in men with bladder outlet obstruction, it is important to be aware of preexisting neurologic conditions. Surgical treatment of bladder outlet obstruction in the presence of detrusor hyperreflexia may result in increased urinary incontinence postoperatively. Finally, patients with sickle cell anemia are prone to a number of urologic conditions including papillary necrosis and erectile dysfunction secondary to recurrent priapism. There are obviously many other diseases with urologic sequelae, and it is important for the urologist to take a careful history in this regard. In addition to these diseases of known genetic predisposition, there are other conditions in which the precise pattern of inheritance has not been elucidated but that clearly have a familial tendency. It is well known that individuals with a family history of urolithiasis are at increased risk for stone formation. More recently, it has been recognized that 8% to 10% of men with prostate cancer have a familial form of the disease that tends to develop about a decade earlier than the more common type of prostate cancer (Bratt, 2000). Other familial conditions are mentioned elsewhere in the text, but suffice it to state again that obtaining a careful history of previous illnesses and a family history of urologic disease can be extremely valuable in establishing the correct diagnosis. It is similarly important to obtain an accurate and complete list of present medications because many drugs interfere with urinary and sexual function. For example, most of the antihypertensive medications interfere with erectile function, and changing antihypertensive medications can sometimes improve sexual function. Similarly, many of the psychotropic agents interfere with emission and orgasm. In our own recent experience, we cared for a man who presented with anorgasmia. He had been to several physicians without improvement in this problem. When we obtained his past medical history, he mentioned that he had been taking a psychotropic agent for transient depression for several years, and his anorgasmia resolved when this no-longer-needed medication was discontinued. The list of medications affecting urinary and sexual function is exhaustive, but, once again, each medication should be recorded and its side effects investigated to be sure that the patient’s problem is not drug related. A listing of common medications that may cause urologic side effects is presented in Table 3–2. Table 3–2 Drugs Associated with Urologic Side Effects

History

Chief Complaint and Present Illness

Hematuria

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

Irritative Symptoms

Obstructive Symptoms

Incontinence

Enuresis

Sexual Dysfunction

Premature Ejaculation

Medical History

Previous Medical Illnesses with Urologic Sequelae

Family History

Medications

UROLOGIC SIDE EFFECTS

CLASS OF DRUGS

SPECIFIC EXAMPLES

Decreased libido

Antihypertensives

Hydrochlorothiazide

Erectile dysfunction

Propranolol

Psychotropic drugs

Benzodiazepines

Ejaculatory dysfunction

α-Adrenergic antagonists

Prazosin

Tamsulosin

α-Methyldopa

Psychotropic drugs

Phenothiazines

Antidepressants

Priapism

Antipsychotics

Phenothiazines

Antidepressants

Trazodone

Antihypertensives

Hydralazine

Prazosin

Decreased spermatogenesis

Chemotherapeutic agents

Alkylating agents

Drugs with abuse potential

Marijuana

Alcohol

Nicotine

Drugs affecting endocrine function

Antiandrogens

Prostaglandins

Incontinence or impaired voiding

Direct smooth muscle stimulants

Histamine

Vasopressin

Others

Furosemide

Valproic acid

Smooth muscle relaxants

Diazepam

Striated muscle relaxants

Baclofen

Urinary retention or obstructive voiding symptoms

Anticholinergic agents or musculotropic relaxants

Oxybutynin

Diazepam

Flavoxate

Calcium channel blockers

Nifedipine

Antiparkinsonian drugs

Carbidopa

Levodopa

α-Adrenergic agonists

Pseudoephedrine

Phenylephrine

Antihistamines

Loratadine

Diphenhydramine

Acute renal failure

Antimicrobials

Aminoglycosides

Penicillins

Cephalosporins

Amphotericin

Chemotherapeutic drugs

Cisplatin

Others

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Phenytoin

Gynecomastia

Antihypertensives

Verapamil

Cardiac drugs

Digoxin

Gastrointestinal drugs

Cimetidine

Metoclopramide

Psychotropic drugs

Phenothiazines

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline

Imipramine

Evaluation of the Urologic Patient: History, Physical Examination, and Urinalysis