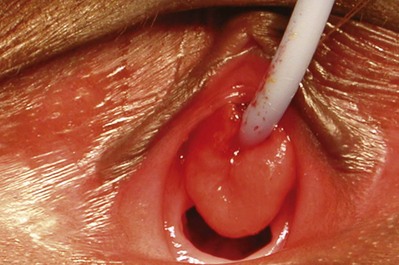

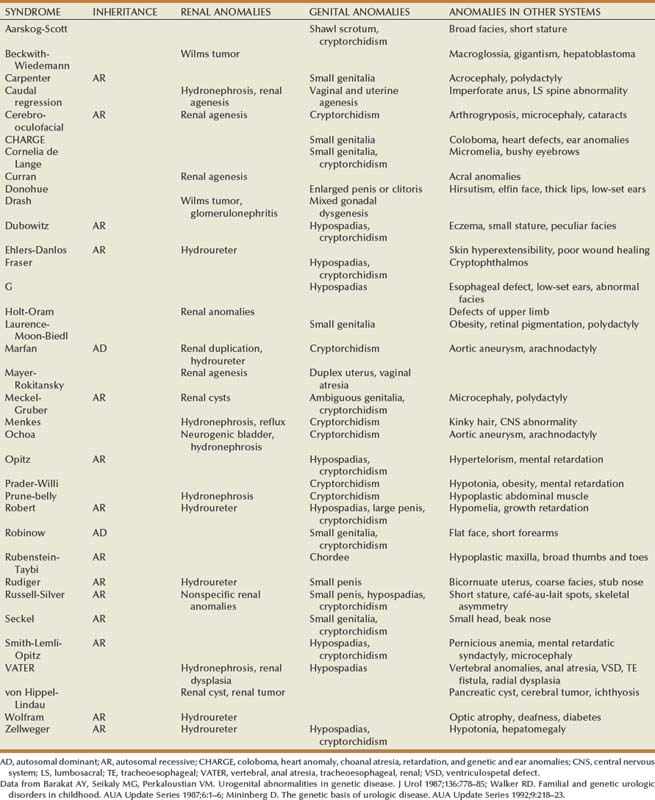

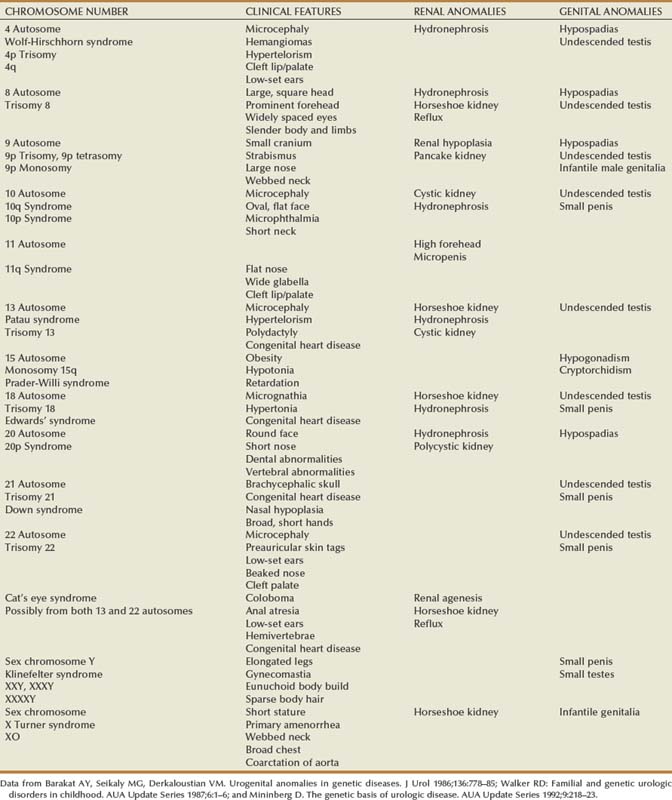

Douglas A. Canning, MD, Sarah M. Lambert, MD Children with acute abdominal pain should be seen immediately. An accurate history of the character of the pain may be the best indicator of the source of the pain. Details about the character of the pain, timing, acuteness of onset, radiation, and migration are important and should, if possible, be elicited directly from the child. Associated loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, or a change in bowel pattern may help to distinguish gastrointestinal from genitourinary sources. Causes of abdominal pain in children vary widely and are often unique to the pediatric population. As urologists, we suspect pyelonephritis, renal colic, or cystitis, but the differential diagnosis includes many nonurologic etiologies. Intra-abdominal causes in children include pyloric stenosis, midgut volvulus, appendicitis, and intussusception. Nonabdominal sources, such as sickle cell crisis, streptococcal pharyngitis, or pneumonia, should also be considered. In addition to a thorough abdominal examination designed to rule out surgical abdominal disease, these children should be evaluated for urinary tract infection (UTI), constipation, and spermatic cord torsion. Usually an acute abdominal series is ordered, which will show considerable amounts of stool throughout the colon if constipation is the problem. Occasionally, some children with spermatic cord torsion complain of abdominal pain and have surprisingly few complaints referring to the scrotum. Most abdominal masses originate in genitourinary organs and should be evaluated immediately (Chandler et al, 2004) (Table 115–1). The most common malignant abdominal tumor in infants is neuroblastoma, followed by Wilms tumor (Golden and Feusner, 2002). Children with neuroblastoma typically relate a history of more constitutional symptoms than children with Wilms tumor. If an abdominal mass is suspected, an abdominal ultrasound evaluation should be ordered. If the mass is solid, computed tomography (CT) is almost always required. Table 115–1 Distribution of Abdominal Masses of 280 Patients in the Neonatal Period* UPJ, ureteropelvic junction; UVJ, ureterovesical junction. * Distended bladder, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly were excluded in most series. Data from Griscom, 1965; Emanuel and White, 1968; Raffensperger and Abousleiman, 1968; Wedge et al, 1971; Wilson, 1982. A child with acute scrotal pain must be presumed to have spermatic cord torsion regardless of age until proven otherwise. However, in some cases, an accurate history may save the child an unnecessary surgical exploration. It is particularly important to interview the child as well as the parent. The differential diagnosis of the acute scrotum includes testicular torsion, torsion of the appendix testis or epididymis, epididymitis/orchitis, hernia/hydrocele, trauma, sexual abuse, tumor, idiopathic scrotal edema, dermatitis, cellulitis, and vasculitis, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura (Gatti and Murphy, 2007). Gradual onset of the pain is more consistent with epididymitis, whereas abrupt pain suggests spermatic cord torsion or torsion of one of the testicular appendices. Associated scrotal wall swelling, erythema, or superior displacement of the testis with an absent cremasteric reflex is suggestive of spermatic cord torsion. Yet, the absence of edema or erythema or the presence of a cremasteric reflex does not rule out the possibility of acute testicular torsion, especially if the onset of pain was recent. The classic presentation of testicular torsion is the sudden onset of severe, unilateral pain that is often associated with nausea and emesis. A history of similar intermittent episodes may suggest intermittent testicular torsion. Traditionally, significant ischemic damage is believed to occur after 4 to 8 hours. Therefore testicular torsion represents a true surgical emergency. Patients presenting after 8 hours should still be explored, because the viability of the testis is difficult to predict (Beard et al, 1977; Bartsch et al, 1980). If there is history of inguinal or scrotal pain, infants and children with an inguinal hernia or a hydrocele that changes in volume should be seen within 24 hours or sooner. Not all of these children will need emergency surgery, but a few will require surgical intervention within a short period. If there is a history of scrotal or inguinal pain, the child’s parents should be taught to recognize the signs of an incarcerated inguinal hernia and instructed to go to the emergency department if symptoms occur before the planned surgical correction. Infants with asymptomatic hydrocele rarely require surgery initially. In most cases, the hydrocele will resolve in the first year of life. The authors make an exception if the hydrocele is particularly large or palpable in the inguinal region. A large hydrocele with a palpable inguinal component or one that is enlarging may indicate the presence of an abdominoscrotal hydrocele. These do not spontaneously resolve and usually enlarge. These should be corrected, usually at 6 to 12 months through an initial scrotal incision that will decompress the hydrocele (Luks et al, 1993; Belman, 2001). Boys with undescended testes are one of the most common referrals to the pediatric urologist. Undescended testes are present in 30% of preterm neonates and are present in 3% of full-term male infants at birth (Ghirri et al, 2002; Boisen et al, 2004). Undescended testes do not represent a surgical emergency. We operate on patients with undescended or absent testes at about 6 months of age. Very few of these testes will descend after 3 months of age (Berkowitz et al, 1993). Some infants with impalpable testes may require laparoscopic evaluation, and this examination may be done at 6 months as well. In prepubertal boys, concerns of an undescended testis often reflect a retractile testis that results from a brisk cremasteric reflex and does not require surgical intervention. A retractile testis must be differentiated from an ascending testis, which may require an orchidopexy. Varicoceles are uncommon in prepubertal boys and increase in incidence to around 15% by 15 years of age (Schiff et al, 2005). We normally try to document the size of the testis with an ultrasound examination. From the three-dimensional measurements on ultrasonography, the relative testicular volumes may be calculated and used to guide further treatment (Diamond et al, 2000). Varicoceles are 90% left-sided and 10% right-sided (MacLellan and Diamond, 2006). A right-sided varicocele in the absence of a left-sided varicocele should prompt an evaluation for a retroperitoneal process. Testicular masses should be evaluated immediately. Prepubertal testicular and paratesticular tumors should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a scrotal mass. Although much less common than epididymal cysts or spermatoceles, a complaint of a painless testicular or paratesticular mass should be addressed urgently. A physical examination and scrotal ultrasonography should determine if the mass is concerning for neoplasia. In a contemporary series from a tertiary center, the most common prepubertal testis tumor was a teratoma, followed by rhabdomyosarcoma, epidermoid cyst, yolk sac tumor, and germ cell tumor, respectively (Metcalfe et al, 2003). This histologic distribution was corroborated by a multicenter review, including four tertiary pediatric hospitals, demonstrating that 74% of tumors were benign, with 48% being teratomas (Pohl et al, 2004). Testicular tumors occur in the newborn and in early childhood as well as after adolescence. It is important to recognize that the peak incidence of testicular tumors in young children and infants occurs at age 2. In this population, yolk sac tumors are most common, and approximately 75% of tumors are malignant (Levy et al, 1994; Ciftci, 2001). Tumors of nontesticular origin, such as leukemia and lymphoma, must also be considered in the pediatric population. Boys with painful priapism must be evaluated immediately. Pain may suggest ischemia of the corporeal bodies, which may progress to corporeal fibrosis if untreated. Children with sickle cell anemia are especially at risk for priapism, with 75% of patients experiencing their first episode by the age of 20 years (Mantadakis et al, 1999; Adeyoju et al, 2002). Outpatient treatment with penile aspiration and epinephrine irrigation has successfully been used in the treatment of this condition (Mantadakis et al, 2000). Paraphimosis also requires immediate attention and manual reduction. In children, this procedure may require some level of sedation. Conversely, phimosis is physiologic in young infants and attempts to manually retract the foreskin in boys less than 2 years of age should be avoided. Phimosis in older children is typically treated with one or two courses of low-dose steroid cream and circumcision if necessary (Ashfield et al, 2003). We evaluate children who have developed a complication after circumcision at the convenience of the family as long as there is no active bleeding, the child is voiding normally, and there is no injury to the penile shaft or shaft skin. Narrowing of the preputial ring after circumcision may result in a trapped penis (Casale et al, 1999; Gillett et al, 2005). These infants can usually be managed with application of petroleum jelly to the penis for 4 to 6 weeks as healing continues. As long as voiding remains normal during this period, the revision of the circumcision may be postponed until age 4 to 6 months when an outpatient surgical procedure can be performed. A more common complication, urethral meatal stenosis, may be present as early as 6 months of age in circumcised infants (Upadhyay et al, 1998; Ahmed et al, 1999). This problem may be easily corrected in the office (Smith and Smith, 2000). Urethral prolapse is relatively common, particularly in young African-American girls. Figure 115–1 demonstrates urethral prolapse in a young girl. A urethral catheter demonstrates the circumferential prolapsed urethral tissue. The prolapse is through the meatus, forming a hemorrhagic, often sensitive mass that bleeds with palpation or when in contact with the undergarments. Girls may have difficulty with urination depending on the size of the prolapse and whether it compromises the urethral meatus. Urethral prolapse may respond to topical application of estrogen and may be managed expectantly as long as voiding is normal (Redman, 1982). Benign and malignant tumors of the vagina should be considered when vaginal bleeding occurs in young girls. A broad spectrum of entities ranging from capillary hemangioma, rhabdomyosarcoma, or carcinoma may be associated with vaginal bleeding. Labial masses may be associated with hernia or hydrocele of the canal of Nuck (Kizer et al, 1995). Adhesions of the labia minora are common. In most cases, they are not symptomatic. Occasionally, a girl with labial adhesions will complain of vaginal irritation from pooled urine. In this case, if the labial adhesions are not separated, the irritation may progress to irregular voiding that may exacerbate the problem of frequency and urgency. In some girls, a short course of estrogen cream applied to the labia may be effective. In many, however, separation of the adhesions in the office with local anesthetic cream may be required. Labial fusion may be associated with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), gonadal dysgenesis, or cloaca (Powell et al, 1995). A genitosinogram may be indicated in cases where the urethra cannot be distinguished from the vaginal orifice and a urogenital sinus is suspected. The authors evaluate adolescent girls who have not menstruated and in whom there is concern about a ureteral or vaginal anomaly within 3 days. Patients with complete androgen insensitivity (CAIS) can also present with primary amenorrhea. Many of these girls have an imperforate hymen or uterine anomaly that results in poor uterine drainage that may be uncomfortable. If left untreated, retrograde drainage of the uterus may place these patients at risk of endometriosis and infertility (Rock et al, 1982). Pelvic ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can further delineate the anatomy and guide intervention if necessary. Like most teams, we see a large number of children of both sexes with voiding complaints and incontinence. Incontinence is classified as diurnal (daytime), nocturnal (nighttime) or both. If a child has never been dry, the incontinence is primary. If the child is wet after a dry interval greater than 6 months, the incontinence is secondary. The ability to place children in categories based on the voiding history will help to focus the rest of the evaluation and guide further therapy. The time and duration of the voiding disorder must be identified early in the interview. A thorough history obtained from both the parents and the child is important to determine the actual pattern of voiding, which may differ from parental perceptions. Did symptoms begin before or after potty training? Is wetting associated with pain, urgency, or frequency? What is the character of the voiding? Is the urinary stream steady from beginning to end or is it a “staccato” or stop and start pattern suggestive of dysfunctional voiding? Are the symptoms worse at a particular time of the day? Does the child void frequently during the day yet sleep through the night without wetting? Is wetting confined to the night, suggestive of primary nocturnal enuresis? Additionally, behavioral signs can be used to further understand the etiology of functional incontinence. Episodes of urgency in children are often suggested by holding maneuvers, such as squatting, crossing legs, and sitting on heels (Ellsworth et al, 2008). Poor potty habits may result in incomplete voiding or vaginal voiding. Giggle incontinence is encountered in young girls and describes large-volume incontinence that occurs only with laughter. In this situation, the incontinence is associated with a complete emptying of the bladder and should be distinguished from stress urinary incontinence in adults because the treatment differs significantly (Berry et al, 2009). The voiding history is incomplete without a record of the child’s eating and drinking pattern. Does the child consume small amounts of water during the day and large amounts of alternative liquids, such as soft drinks and juices, which tend to be laden with salt and sugar and low in free water? What is the stooling pattern? Does the child have firm, chunky, or pebble-like bowel movements suggestive of a retentive pattern of stooling, or does the child have soft, well-formed bowel movements more suggestive of a normal stooling pattern? Very few children hold the urine and not the stool. Conversely, children who retain stool nearly always retain urine. All of these are indicators of a dysfunctional voiding pattern, which may lead to UTI. Referencing a standardized stool chart, such as the Bristol stool form scale (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bristol_Stool_Scale; Lewis and Heaton, 1997) may be helpful to further clarify the stooling pattern (Koh et al, 2010). Although genital injuries may be accidental, the possibility of physical or sexual abuse must be considered in all cases of genital trauma in females or males. Sexual abuse is surprisingly common and includes any activity with a child before the age of legal consent that is for sexual gratification of an adult or a significantly older child. Sexual intercourse includes vaginal, oral, or rectal penetration, which is defined as entry into an orifice with or without tissue damage. Sex acts perpetrated by young children are learned behaviors and are associated with experiencing sexual abuse or exposure to adult sex or pornography. In 2007, there were more than 740,000 reported cases of child maltreatment. Included in this number were 56,460 victims of sexual abuse in the United States. Of these children, 18% were less than 4 years of age, 23% were 4 to 7 years of age, 24% were 8 to 11 years of age, and 35% were 12 to 15 years of age. The perpetrators of the sexual abuse are most commonly a friend or neighbor, followed by a relative or daycare worker (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). In a recent review, the peak incidence of sexually transmitted diseases was seen in the 10- to 14-year age group (Pandhi et al, 2003). In one study of women presenting to an urban sexual assault clinic, 43% were adolescents (Jones et al, 2003). Pelvic inflammatory disease rates are highest in females age 15 to 25 with 33% of those infections in females younger than age 19 (Jenkins, 2000). Any pediatric patient with a sexually transmitted infection should be evaluated for sexual abuse. Although the mode of transmission of human papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is often unclear, Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis infections in a prepubertal child should be reported to child protective services (Bechtel, 2010). The possibility of sexual abuse should be considered a result of associated physical symptoms, including (1) vaginal, penile, or rectal pain, discharge, or bleeding or (2) chronic dysuria, enuresis, constipation, or encopresis. In one study, 74% of pediatric patients with documented sexually transmitted diseases had histories or signs of abuse (Pandhi et al, 2003). Sexual abuse should be considered when the vaginal mucosa is bruised or injected, the vaginal opening is dilated, or the hymen is damaged, showing a V-shaped notch or cleft (Walker, 1998). Despite these guidelines, the diagnosis of sexual abuse is often made by the history and not by the physical examination. In a review of 506 girls with a history of penetrative abuse referred to a sexual abuse clinic, only 11% had examination findings suggestive of sexual abuse (Anderst et al, 2009). Investigating the possibility of sexual abuse requires supportive, sensitive, and detailed history taking. Many hospitals have a sexual abuse team that can be consulted if sexual abuse is suspected. The key is to be aware of the possibilities when they might exist and to invite the team in early. The pediatric urologist will likely be asked to evaluate the abdomen and perineum (Johnson, 2000). If abuse is suspected, it must be reported to the police. Furthermore, if the perpetrator is a caregiver of the child, or a parent, the state child welfare team must be contacted. Febrile UTIs in the newborn are treated emergently, because newborns are particularly susceptible to significant renal damage if the infection is not treated promptly. A urine culture should be obtained, and these infants require intravenous antibiotics as early as possible after a urine culture has been obtained, because they have a higher prevalence of concomitant bacteremia (10% to 22%) (Pitteti and Choi, 2002). Appropriate antibiotic therapy administered without delay has been shown to reduce the incidence of scarring (Ransley and Risdon, 1981; Hiraoka et al, 2003). Some authors suggest this decreased incidence of scarring reflects a decreased likelihood of renal involvement rather than a true prevention of scar formation (Doganis et al, 2007). Febrile UTIs in children older than newborns should be treated acutely. Children of all ages with a severe urinary tract infection may be subject to renal scarring (Ransley and Risdon, 1981; van der Voort et al, 1997) and should be seen within 24 hours or sooner. Children older than newborns with nonfebrile UTI should be seen semiurgently. In practice, many of these patients are seen by their pediatrician and are seen in follow-up by the pediatric urologist. Nearly all children with culture-proven UTI should be evaluated with ultrasonography and VCUG, although some groups are re-evaluating the role of renal nuclear scans in these children. The evaluation for UTI is completed at the parent’s convenience after the initial infection has been treated. In most cases, radiologic studies after UTI in a child include VCUG to detect vesicoureteral reflux. However, a substantial number of cortical defects on dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphy (DMSA) scan occur in the absence of identifiable reflux (62% to 82%) (Majd and Rushton, 1992; Benador et al, 1997; Ditchfield and Nadel, 1998; Biggi et al, 2001; Ditchfield et al, 2002). This has led to a re-evaluation of the role of VCUG as the initial investigation in a child with a UTI. It is important to recognize that infants less than 6 months of age and uncircumcised male infants are at increased risk for recurrent UTI (Wiswell and Roscelli, 1986). A practical approach to the evaluation of hematuria in children is presented in Chapter 112. The authors’ recommendation for patients with microscopic hematuria with unrelated clinical symptoms is to treat the affiliated illness (e.g., pulmonary or immunologic conditions, glomerular and interstitial disease, lower urinary tract disease, stones, tumors, vascular disease, or acute abdominal conditions) and ignore hematuria until the treatment for the underlying illness is underway. Transient microhematuria is also common in healthy children (Vehaskari et al, 1979). The large majority of children with microscopic hematuria are evaluated, and the source of the hematuria is never identified (Diven and Travis, 2000). Notably, the most commonly identified etiology of asymptomatic microhematuria and gross hematuria in children is hypercalciuria (Parekh et al, 2002; Bergstein et al, 2005). Microscopic hematuria in the absence of other symptoms is not an emergency in children. Gross hematuria in children is less common than microscopic hematuria, with an estimated prevalence of 1.3 per 1000 (Ingelfinger et al, 1977). The most common diagnoses are UTI (26%), perineal irritation (11%), trauma (7%), meatal stenosis with ulceration (7%), coagulation abnormalities (3%), and urinary tract stones (2%). The most common glomerular causes of gross hematuria in children are poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and IgA nephropathy. An antecedent sore throat, pyoderma, edema, or red blood cell casts suggest glomerulonephritis. IgA nephropathy can cause recurrent gross hematuria with flank or abdominal pain and may be preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection (Meyers, 2004). Adenoviral infection, hypercalciuria, and hyperuricosuria are other sources to consider. In peripubertal boys, benign urethrorrhagia can present with terminal gross hematuria. The authors perform ultrasonography of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder in children with gross hematuria, although the yield is low (Fernbach, 1992). In contrast with the adult patient, cystoscopic examination in children rarely reveals a cause for hematuria but should be performed when bladder pathology is a consideration. Gross hematuria in the newborn is an emergency because it may indicate renal venous thrombosis or renal arterial thrombosis. Both may be life-threatening. Renal venous thrombosis affects boys twice as often as girls, with a left-sided predominance. These infants require resuscitation and, occasionally, anticoagulant or operative therapy (Kuhle et al, 2004). Gross hematuria outside the newborn period, although not life-threatening, should be evaluated without delay. Many children have an easy-to-recognize source such as UTI, urethral prolapse, trauma, and meatal stenosis with ulceration, coagulation abnormalities, or urinary tract stones. Less obvious sources include acute nephritis, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, cystitis cystica, epididymitis, or tumor (Diven and Travis, 2000; Meyers, 2004). As with adult patients, a thorough history including a specific description of the color of the urine, the presence of clots, and timing of hematuria, such as terminal hematuria or hematuria upon initiation of micturition, should facilitate the diagnostic process. A directed history should include medications, exercise habits, propensity for bleeding diathesis, and a travel history to rule out exposure to infectious diseases such as schistosomiasis or tuberculosis. The pediatric trauma patient usually presents to the emergency department and is evaluated by the emergency medicine and trauma teams, often with the assistance of the urology service. Blunt force trauma is the primary mechanism for major renal trauma (Mohamed et al, 2010). The pediatric kidney is particularly susceptible to trauma due to the limited visceral adipose tissue, limited chest wall protection, relatively increased renal size, and increased mobility of the kidney (Brown, 1998). The mechanism of injury should be determined and a thorough history obtained from the patient and caregivers or observers. Epidemiologic data demonstrate that the majority of renal injuries result from motor vehicle accidents, falls, or high-velocity activities, such as sledding, skiing, all-terrain vehicle accidents, and skateboarding (Margenthaler et al, 2002; Rogers, 2004). Therefore injuries of this nature should alert the clinician to potential renal damage. The history should include any congenital renal anomalies, such as an ureteropelvic junction obstruction, a solitary kidney, or renal ectopia. Finally, evaluation of associated injuries must be undertaken. Any abdominal injury in a toddler or young child without an antecedent history of blunt force trauma should be evaluated for physical abuse (Barnes et al, 2005). Blunt force renal trauma represents a urologic emergency that requires immediate attention but does not necessarily require operative intervention. It is well accepted that low-grade blunt renal injuries are managed conservatively. More recently, the conservative treatment of high-grade blunt renal injuries have been successfully described in children. A consecutive series of 101 patients from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) with blunt renal injury demonstrated that a nonoperative management strategy was advantageous and successful in 94.7% of pediatric blunt renal injuries (Nance et al, 2004). The children with high-grade injuries at risk for failure of conservative management include those with major vascular avulsion or extensive urinary extravasation, especially in the setting of ureteropelvic junction disruptions (Henderson et al, 2007). These patients deserve close urologic observation and repeated examinations. The authors recommend conservative management and recognize that a complete evaluation is necessary to accurately determine which patients require further intervention. Infants with ambiguous genitalia also require immediate evaluation. Many will require direct transfer from a referring hospital. Because CAH may result in salt wasting, which may be life threatening, infants with ambiguous genitalia must be evaluated quickly and stabilized (Forest, 2004). If CAH is suspected, the infant should not be discharged home from the nursery before appropriate testing is complete. In some cases, a genotypic female neonate with CAH may be incorrectly identified as a male neonate. The correct diagnosis should be made as quickly as possible to establish the appropriate sex of rearing. Infants with ambiguous genitalia may also have other syndromes and may require further evaluation (Tables 115-2 and 115-3). A history of a discordant karyotype from an amniocentesis and infant phenotype should prompt an evaluation. The parents should be asked about a family history of infertility, amenorrhea, and infant mortality. The complete evaluation of infants with ambiguous genitalia should include urology, neonatology, endocrinology, genetics, and radiology. Patients with major abdominal defects, such as bladder or cloacal exstrophy, require direct admission to the neonatal nursery for stabilization and surgical planning. In many cases, a team is assembled and provides orthopedic, general surgical, and urologic care during the surgery (Jeffs, 1978; Lattimer et al, 1979; Gearhart, 1999). Patients with imperforate anus and variants, such as a cloacal anomaly, require decompression of the intestinal tract, usually within the first 24 to 48 hours (Chen, 1999). At the time of the colostomy, the urologist may evaluate the perineum and perform endoscopy to further assess the urinary anomalies. Procedures to correct these major defects must be planned by surgeons who are familiar with the potential risks and complications associated with the reconstruction of the urethra, vagina, and colon. The anesthesia team must be skillful in the management of the complex metabolic changes that may occur in infants who are under anesthesia for long periods. The neonatologists must be expert in the management of infants who have undergone major surgical procedures. Today, many newborns with spinal dysraphisms are diagnosed in utero (Babcook et al, 1995). These infants are referred by direct admission to the neonatal intensive care nursery. Most of these children are not in urinary retention initially, but many develop spinal shock after neurosurgery in the newborn period and have a transient period of overflow urinary drainage. As soon as possible after closure of the spinal defect, a baseline renal and bladder ultrasonogram is performed to evaluate for evidence of bladder or upper tract abnormalities. Initial urodynamics investigation is performed after resolution of the spinal shock to ensure that bladder storage pressures are not excessive (McGuire et al, 1977, 1983; Bauer, 1998; Tarcan et al, 2001). High-risk infants (those with a detrusor leak-point pressure greater than 40 cm H2O or detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia) are started on anticholinergic therapy and intermittent catheterization (Snodgrass and Adams, 2004

Chief Complaint and History of Present Illness

Abdominal Complaints

TYPE

NO.

Kidney (65%)

Hydronephrosis (UPJ obstruction, UVJ obstruction,

80 (28%)

ureterocele, etc.)

Multicystic kidney

63 (22%)

Polycystic kidney disease

18

Renal vein thrombosis

5

Solid tumor

13

Ectopy

4

TOTAL

183

Retroperitoneum (9%)

Neuroblastoma

17

Teratoma

3

Hemangioma

1

Abscess

4

TOTAL

25

Bladder (1%)

Posterior urethral valves

2

Female Genital System (10%)

Hydrocolpos

16

Ovarian cyst

13

TOTAL

31

Gastrointestinal (12%)

Duplication

17

Giant cystic meconium ileus

4

Mesenteric cyst

3

Ileal atresia

2

Volvulus (ileum)

2

Teratoma (stomach)

1

Leiomyosarcoma (colon)

1

Meconium peritonitis with ascites

1

Ascites

1

TOTAL

32

Hepatic or Biliary (3%)

Hemangioma (liver)

3

Solitary cyst (liver)

2

Hepatoma

1

Distended gallbladder

1

Choledochal cyst

1

Adenomatoid malformation of the lung

1

TOTAL

9

Scrotal Symptoms

Male Penile or Urethral Symptoms

Female Genital Symptoms

Voiding Symptoms

Sexual Abuse

Urinary Tract Infection

Hematuria

Renal Trauma

Ambiguous Genitalia

Congenital Anomalies in the Neonate

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Evaluation of the Pediatric Urology Patient