ISDN isosorbide dinitrate.

Modified from Vaezi M, Richter JE. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21–35.

Nitrates activate guanylate cyclase, leading to production of a protein kinase that inhibits smooth muscle contraction through dephosphorylation of the myosin light chain. Additionally, nitrates liberate nitric oxide (NO), an inhibitory neurotransmitter mediated by cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). Significant reduction of LES pressure has been demonstrated 10 minutes after sublingual administration of a 5mg dose of isosorbide dinitrate [9]. Very few randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effect of nitrates on achalasia. Wong et al. [10] found a significant decrease in LES pressure and significant improvement in esophageal emptying 30 minutes after a single dose (0.4mg) of sublingual nitroglycerin in a randomized crossover study. In several other small studies [11–14], nitrates have decreased LES pressure by 30–65%, with symptom improvement in 58–87% of patients (Table 4.1), but these were uncontrolled studies that traditionally tend to overemphasize the benefits of interventions. Calcium channel blockers produce smooth muscle relaxation by decreasing entry of calcium, necessary for contraction, into smooth muscle cells. In a double-blind randomized controlled trial in 10 achalasia patients [15], sublingual nifedipine (10–30 mg dose, titrated according to patient tolerance) given before meals achieved a significant reduction in LES pressures 30 minutes after administration. However, despite this reduction, LES pressures were still substantial after treatment (mean LES pressure of 30mmHg). These investigators also reported a modest improvement of dys-phagia with nifedipine, with a reduction in the average number of meals per day with dysphagia from 1.9 to 0.9. Ald Other uncontrolled studies suggest that calcium channel blockers decrease LES pressure by 13–49% and improve symptoms in 53–77% of patients [11, 12, 15–17]. B4

In a small randomized controlled trial comparing calcium channel blockers and nitrates in 15 patients, 12 found sublingual isosorbide dinitrate (5 mg) to be superior to sublingual nifedipine (20 mg) for the treatment of achalasia. Ald In comparison to nifedipine, isosorbide dinitrate achieved a more pronounced reduction in basal LES pressure (47% vs 64%). Additionally, more patients receiving isosorbide dinitrate experienced complete radionuclide meal clearance at 10 minutes (53% vs 15%) and relief of dysphagia (87% vs 53%).

Sildenafil (Viagra) inhibits smooth muscle contraction by promoting accumulation of NO stimulated cGMP (NO-cGMP) through inhibition of NO phosphodiesterase type 5, an enzyme that degrades NO-cGMP. Recently, in a placebo-controlled randomized trial of sildenafil (50 mg) in 14 achalasia patients, Bortolotti et al. [18] showed that sildenafil by direct intragastric infusion significantly reduced basal LES pressure, post-deglutitive LES residual pressure and esophageal body contraction amplitude. Peak effect was reached 15–20 minutes after infusion and lasted less than one hour. Eherer et al. [19] administered sildenafil orally (50 mg) to 11 patients with esophageal motor disorders, three of whom had a diagnosis of achalasia. LES pressure decreased in two of these patients, but none had relief of symptoms.

Overall, nitrates and calcium channel blockers can reduce LES pressure. The effect on symptoms is variable, shortlived, and usually suboptimal. Ald Additionally, adverse effects such as headache, hypotension, and pedal edema that are frequent may limit their use [11]. Therefore, these agents should be reserved for the short-term relief of achalasia symptoms, either as a temporizing measure while awaiting more definitive therapy, or in patients who are too sick or unwilling to undergo other treatments. Sildenafil merits further study in randomized controlled trials.

Botulinum toxin

Endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the LES is a relatively recent addition to the treatment options for achalasia. It produces reduction in LES pressure by inhibiting acetylcholine release from nerve endings, thereby counterbalancing the effect of the selective loss of inhibitory neu-rotransmitters (nitrous oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide) in achalasia. It is safe, easy to administer and provides symptom relief initially in approximately 85% of patients; however, the effect of a single injection is usually limited to six months or less in over 50% of patients [3]. B4.

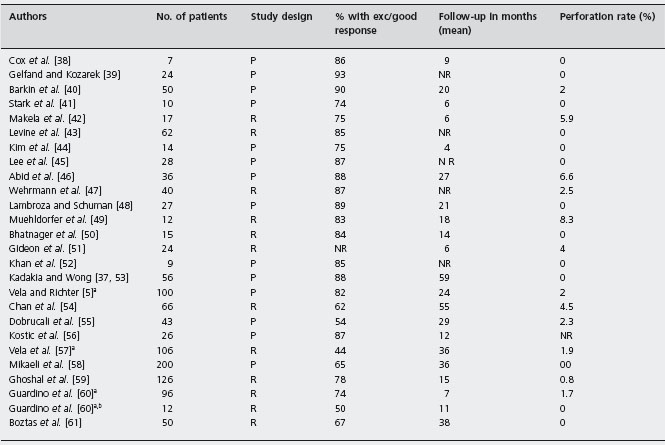

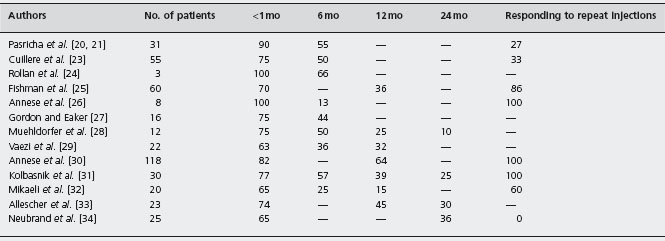

In a six-month randomized controlled trial of 21 patients, the administration of botulinum toxin (100 units) resulted in significant symptom score improvement (from 7.1 ±1.2 to 1.6 ±2.2), compared to placebo (from 5.9 ± 1.6 to 5.4 ± 2.0) (p = 0.001) at one week. By six months the proportion of patients in remission had declined from 82% to 66% [20]. Ald A subsequent study by the same group [21] evaluated the efficacy of botulinum toxin over a 2–3-year period and found that 65% (20/31) of patients had good symptom improvement at six months. However, 19 of these 20 responders eventually relapsed, requiring repeat injections, and two-thirds of the patients eventually chose a more definitive form of therapy. In the analysis of sub-goups in this small study the response rate appeared to be higher for patients over the age of 50 years and those with the “vigorous” form of achalasia. Subsequent studies [20–34] have confirmed that botulinum toxin is initially effective, but the benefit of a single injection lasts less than one year in the majority of patients, with all patients requiring repeat injections or other forms of therapy for their achalasia (Table 4.2). Ald, B4 Botulinum toxin is extremely safe, with 25% of patients presenting with transient, mild, post-procedural chest pain, and 5% developing symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [6].

Table 4.2 Botulinum toxin injection for the treatment of achalasia: symptomatic improvement after one injection.

mo: months.

Modified from Hoogerwerf WA et al. Gastrointest. Endosc Clin North Am 2001; 11: 311–323 [22].

Botulinum toxin is an effective and safe option for the short-term treatment of achalasia. Symptoms are relieved on average for six months with repeat treatments being required to keep patients in long-term remission. Botulinum toxin is inferior to pneumatic dilatation or surgery (see comparative studies below), but it can be particularly useful in the elderly, who may have a higher response rate than younger patients (under age 50 years) and who may have a life expectancy of ≤2 years. Clouse et al. showed the survival analysis curve did not differ significantly for repeated botulinum toxin injections compared to pneumatic dilation at year 1 and year 2 (p = 0.5 and p = 0.4 respectively) [35].

Pneumatic dilatation

Disruption of the muscle fibers of the LES through forceful dilatation has been used as treatment of achalasia for many years. The first description of dilatation dates from 1674 when a patient with achalasia was treated by passing a piece of carved whalebone with a sponge affixed to the distal end down the esophagus into the stomach [7]. The first pneumatic (i.e. air filled) dilators were introduced in the late 1930s, and both the equipment and technique have evolved over the years. Not only are the dilators and techniques varied, but the definitions of success differ across studies. However, there is sufficient experience with the currently used balloon dilators to comment on their efficacy and safety.

Kadakia and Wong calculated the pooled effect of the older dilators (Brown-McHardy Mosher and Hurst-Tucker balloons) among a total of 235 patients studied in five prospective studies. Symptomatic response was excellent or good in 61–100% of patients who were followed for a mean of 2.7 years [36]. B4 Currently, the most widely used dilator in the USA is the Rigiflex polyethylene balloon (Boston Scientific, Boston), which is available in three different diameters (30, 35 and 40 mm) [11]. The current technique consists of endoscopy to determine landmarks, followed by placement of a balloon across the LES, usually under fluoroscopic guidance. The balloon is then inflated to sufficient pressure (usually 7–12 psi; 48.3–82.7kPa) for up to 60 seconds to disrupt the muscle fibers of the LES.

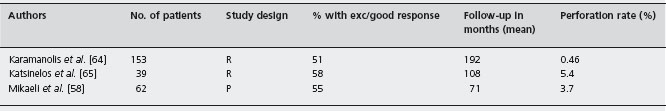

There are no clinical trials that compare pneumatic dilatation to placebo (i.e. sham dilatation). In recent randomized controlled trials comparing pneumatic dilatation to Botulinum toxin injection, symptom improvement rates for dilatation at 12 months ranged between 53% and 70% [28, 29, 32]. Ald Table 4.3 summarizes the results of 26 uncontrolled studies of Rigiflex pneumatic dilatation for the treatment of achalasia with <5 years follow-up [5, 37–61], the degree of heterogeneity of these studies is not known. The pooled results of 1256 patients followed for a mean of 20 months yield an excellent to good response in 77% of patients. B4 However, it should be emphasized that uncontrolled studies tend to exaggerate the benefits of interventions, and the criteria used to determine the response to treatment varies among studies. Furthermore, while a graded approach to pneumatic dilation using repeat treatment with a larger balloon size is considered standard, in some studies a repeat procedure within a graded dilation protocol is considered a failure. Zerbib et al. [62] used an iterative approach with pneumatic dilation based on recurrence of patient symptoms. In their protocol, graded dilations were performed every 2–3 weeks until remission occurred. Patients were considered treatment failures with persistent symptoms after four or five procedures and only 11 of 150 failed with this approach. B4

P: prospective; R: retrospective; NR: not reported.

a Patients in these studies overlap.

b Patients S/P Heller myotomy.

Modified and updated from Vaezi M F, Richter JE. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21–35 [11] and Gelfand MD and Kozarek RA. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84: 924–927 [39].

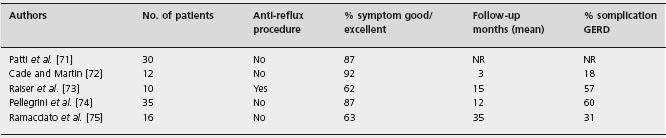

Another important issue is the relative paucity of long-term outcome studies of pneumatic dilatation. There have been few randomized controlled trials evaluating pneumatic dilation performed with the currently available balloons. In the most recent trial by Kostic et al. that included 26 patients treated with pneumatic dilation and followed for 12 months, 77% of patients improved with treatment [56]. In an older randomized controlled trial with follow-up extending beyond 12 months, 50% of patients treated with pneumatic dilatation had relapse of dysphagia at 30 months [28]. Ald West et al. [63] reported on the success of pneumatic dilatation in patients followed for more than five years. Although this study was characterized by serious methodological limitations, including the use of different types of balloons and the use of a symptom questionnaire to define therapeutic success, it was the first study with extended follow-up. The overall therapeutic success rate was 50% in 81 patients followed for more than five years, and the mean number of dilatations per patient was four. Success rate decreased in patients with longer follow-up: 60% in patients followed between 5 and 9 years, 50% for those followed between 10 and 14 years, and 40% in the group followed for more than 15 years. B4 There have been three subsequent studies with extended follow-up beyond five years. The success rate in 254 pooled patients reached 55% after a mean follow-up period of ten years (Table 4.4) [58, 64, 65].

P: prospective; R: retrospective.

Modifi ed and updated from Vaezi M F, Richter JE. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21 – 35 [11] and Gelfand MD and Kozarek RA. Am J Gastroenterol 1989; 84: 924 – 7 [39].

The overall perforation rate associated with pneumatic dilatation is approximately 2% (this varies across different studies, from as low as 0%, to as high as 8%) [11]. Mortality from the procedure is estimated to be 0.2% [6]. Gastroesophageal reflux after pneumatic dilatation occurs in 15-33% of patients [5, 35]. Ald B4 Overall, pneumatic dilatation results in good to excellent symptom relief in approximately 80% of patients based upon follow-up of one or two years. However, the limited long-term follow-up data suggest that the remission rates decline with time and the few studies with extended follow-up periods beyond five years indicate a 57% success rate [58, 64, 65]. That said, pneumatic dilatation is the most effective non-surgical treatment available for achalasia and has a success rate comparable with that of surgery (see comparative studies below). It should be considered an acceptable alternative to surgery for treatment of achalasia.

Heller myotomy

Surgical myotomy was originally described by Ernest Heller in 1914 and involved cutting the anterior and posterior aspects of the LES through a thoracotomy [66].The surgical technique has evolved first with a laparotomy approach and again with the advent of minimally invasive surgery in the 1990s. While a thoracoscopic approach has been used, laparoscopic myotomy has become the preferred method, as it is associated with less morbidity and quicker recovery times [67]. Whether an anti-reflux procedure should be performed (to prevent reflux) or not (to avoid postoperative dysphagia) has been a matter of controversy [3, 7]. Recent studies by Rice et al. and Richards et al. determined that the addition of anterior fundoplication (Dor) does reduce the amount of acid reflux following Heller myotomy [68, 69]. In the study conducted by Rice et al., the esophageal acid exposure time in the upright position varied from 0.4% with anterior fundoplication to 2.9% without (p = 0.005). The same study compared the incidence of reflux, resting LESP, and esophageal emptying. The addition of a Dor fundoplication resulted in significantly less reflux (0.4% vs 2.9% p = 0.005), a higher LESP (18mmHg vs 13mmHg p = 0.002), and no difference in the esophageal emptying (p = 0.6) [68]. Similar results were demonstrated by Richards et al., who observed that the addition of anterior fundoplication decreased the amount of reflux (p = 0.005), without increasing dysphagia scores [69]. These limited data indicate that anti-reflux procedures may decrease post-esophagomyotomy reflux without impairing emptying, but the long-term effect on this balance is still unknown.

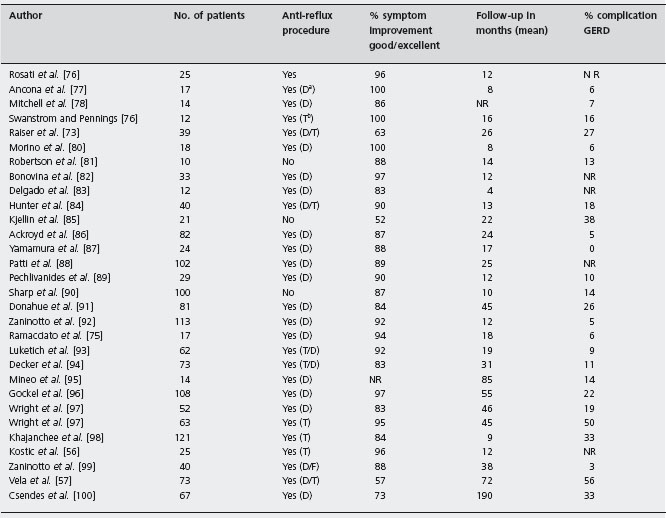

Minimally invasive surgery and especially laparoscopy, has become the standard approach to perform myotomy. Uncontrolled studies of the thoracoscopic [11, 70–75] and laparoscopic [11, 56, 57, 75–100] techniques are summarized in Tables 4.5 and 4.6 respectively. Pooled results of 103 patients in five studies of thoracoscopy yield good to excellent symptom response in 82% of patients with a mean follow-up of 16 months, although GERD developed in 42% of patients. The pooled symptom response rate was 84% in 1420 patients undergoing laparoscopic or open Heller myotomy in 30 uncontrolled trials; 37% of these patients developed GERD [11, 56, 57, 75–100]. B4

As with pneumatic dilation, the efficacy of Heller myotomy decreases with longer follow-up periods. In a series of 73 patients treated with Heller myotomy, excellent/good responses were reported in 89% and 57% of patients at six months and six years’ follow-up [57]. Csendes et al. observed 80% of patients with good/excellent results at 7–10 years, 74% at 10–20 years and 65% at >20 years [100].

Modified and updated from Vaezi MF, Richter JE. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21–35 [11]. NR: not reported; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease.

aD, Dor.

bT, Toupet.

cF, Floppy Nissen.

P: prospective; R: retrospective; NR: not reported.

Modified from Vaezi MF, Richter JE. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 27: 21–35 [11].

As stated earlier, the degree of benefit may be overestimated in uncontrolled studies. Heller myotomy, preferably through the laparoscopic approach, should be considered as effective as pneumatic dilatation and should be offered to patients who present an acceptable surgical risk. It can also be offered to those who have failed pneumatic dilatation.

Comparisons of different treatment modalities

Pneumatic dilatation versus botulinum toxin These two therapeutic approaches have been compared in three randomized controlled trials (Table 4.7). Ald Vaezi et al. [29] randomized 42 patients to receive botulinum toxin injection or graded pneumatic dilatation with 30 and 35 mm Rigiflex balloons and reported success at 12 months (defined as improvement in symptom score greater than 50%) to be 70% for dilatation and 32% for botulinum toxin. Using a similar design and criteria for symptom response, Mikaeli et al. [32] reported response rates at 12 months of 53% with single pneumatic dilatation and 15% with a single botulinum toxin injection. Success after repeat dilation or repeat injection was observed, respectively, in 100% and 60% of patients at 12 months. Muehldorfer et al. [28] randomized 24 patients to botulinum toxin or dilatation with a 40 mm latex balloon; symptomatic response was superior with pneumatic dilatation compared with botulinum toxin at 12 months (67% vs 25%) and at 30 months (50% vs 0%). Identification of predictors of response was not possible in any of these three small randomized trials. Although randomization codes were concealed, patients and investigators were not blinded as to the treatments received.

Two studies have compared the costs of Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilation and botox injection. The costs per symptomatic cure over a ten-year horizon were $10,792 for Heller myotomy, $3723 for BoTox injection, and $3111 for pneumatic dilation [101]. A cost-effectiveness study that accounted for quality of life over a five-year horizon determined the costs of BoTox injection, pneumatic dilation and Heller myotomy to be $7011, $7069, and $21,407 respectively. While the cost of BoTox was slightly lower, PD was more cost-effective, with an incremental cost-effectiveness of $1348 per QALY (quality adjusted life year) [102].

Heller myotomy versus botulinum toxin There is only one prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of laparoscopic myotomy and botulinum toxin injection. A total of 80 patients were randomized to either treatment group. The lower esophageal resting and relaxation pressures, esophageal body dilation, and dys-phagia/regurgitation scores were all measured before and after treatment. After six months there was a greater symptom reduction (82% vs 66%) in the myotomy group compared to the BoTox group. The two-year probability of remaining symptom free was 87% after myotomy and 34% after BoTox. Median LESP was significantly lower in the surgery group (27mmHg vs 36mmHg p < 0.05). The esophageal body diameter was not significantly different 4.1cm vs 3.5cm [99]. Two cost minimization studies compared Heller myotomy, pneumatic dilation and botox injection. Heller myotomy was associated with greater costs compared to BoTox injection in both studies (US$10,792 vs $3723 and US$21,407 vs $7011) [103].

Pneumatic dilatation versus Heller myotomy The first randomized controlled trial that compared pneumatic dilatation to myotomy [70, 100] found that myotomy via laparotomy had a success rate of 95% compared with 65% for pneumatic dilatation with the Mosher bag. Ald Neither of these techniques are widely used today, and the results may not be generalizable to other techniques. Spiess and Kahrilas [7] pooled all uncontrolled series of ten or more patients undergoing pneumatic dilatation or surgery with follow-up greater than a year performed between 1966 and 1997. They reported response rates as weighted means and found good to excellent symptom response in 80 ± 42% of participants with pneumatic dilatation. Response rates for surgery were 84 ± 20% with thoracotomy, 85 ± 42% with laparotomy, and 92 ± 18% with laparoscopy. However, criteria for including or excluding reports were not stated, and these uncontrolled studies may tend to overestimate the benefits of treatment. B4 Kostic et al. [56] were the first to conduct a randomized controlled trial comparing patients treated with current techniques, laparoscopic Heller myotomy and pneumatic dilation with the Rigiflex balloon. The results of this trial showed 96% success in the myotomy group versus 87% in the dilation group during a 12-month follow-up period compared to the data reported by Csendes (95% vs 65%). The duration of treatment response for either intervention is not clear, as most studies include follow-up periods <5 years. Vela et al.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree