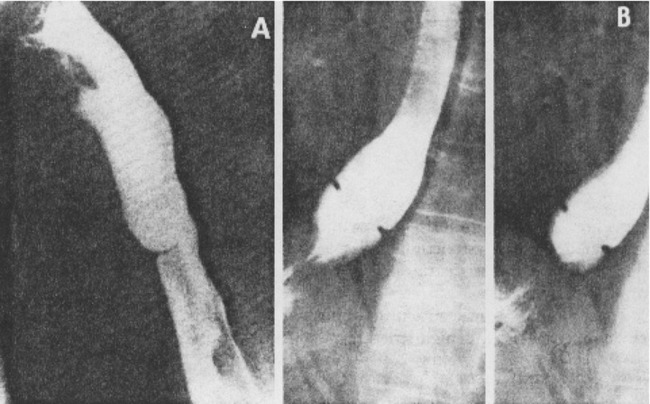

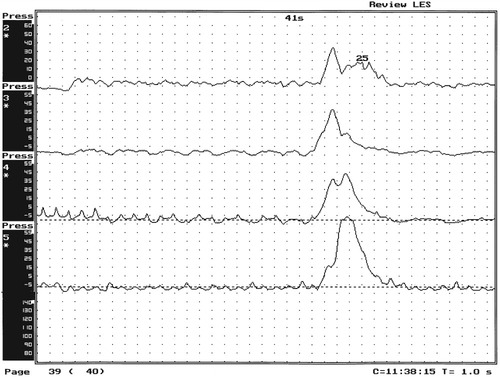

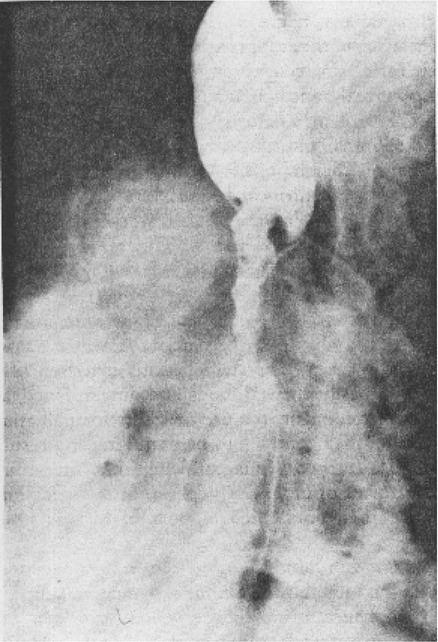

1. Discuss the structural disorders of the esophagus that affect swallowing. 2. Discuss the motor disorders of the esophagus that affect swallowing. 3. Detail disorders of the pharyngoesophageal segment. 4. Show how disorders of esophageal origin might affect other aspects of the swallowing chain. 5. Discuss possible treatment approaches for swallowing disorders of esophageal and pharyngoesophageal origin. Esophageal stenosis is conceptually the easiest mechanism of dysphagia to understand. When the lumen narrows, solid food may be too large to pass through it. Esophageal stenosis typically causes dysphagia for solid food. In addition, the type of solid material ingested often is important for symptom production. For instance, dysphagia of esophageal origin is more likely when solids are tough or fibrous. Softer, more easily chewed foods are much less likely to cause symptoms of esophageal dysphagia. An exception to this tough food–soft food dichotomy is that many patients also have particular trouble with soft, absorbent foods such as bread or pasta, which swell when mixed with saliva during mastication. Once bolus impaction occurs, the patient may have difficulty with liquids as well, obscuring the characteristic solids-only nature of esophageal stenosis. However, a careful history usually reveals that liquid dysphagia begins with ingestion of solids (see differential diagnosis later in this chapter). Clinicians often rely too much on the patient’s sensation of where food is sticking. The common wisdom that patients accurately localize symptoms to the site of obstruction is often inaccurate. In fact, approximately one third of patients with obstructing lesions of the distal esophagus point to the neck as the site of obstruction.1 Conversely, one third of patients with dysphagia localized to the pharynx have an isolated abnormality of the esophagus.2 It is surprising how well some patients fare despite dramatic stenosis. Based on radiographic observations in patients with Schatzki’s rings, it is often stated that patients with luminal diameters of more than 18 to 20 mm are never symptomatic, whereas those with diameters less than 10 to 12 mm are always symptomatic.3 When the radiologist examines the esophagus for suspected stenosis, a radiopaque pill that is 13 mm in diameter is used to detect a stenosis. Between these extremes (20 and 10 mm), symptoms vary both in frequency and severity depending on the presence of associated motor dysfunction and the choice and preparation of food. Stenosis is treated by opening or removing the narrowed segment, depending on the specific cause. This is usually accomplished with Maloney (bougie) dilators or with balloon dilatation. Although classically described in patients with iron-deficiency anemia (sideropenic dysphagia), the majority of esophageal webs are not associated with iron deficiency. Webs of the pharyngoesophageal segment or cervical esophagus are frequently asymmetric, most often impinging on the esophageal lumen from the anterior wall (Figure 7-1, A). A suspected web at the cervical level also can be seen in Video 7-1 on the Evolve site accompanying this text. Schatzki’s rings are the most common bandlike constriction of the esophagus. This lesion is typically symmetric and located at the esophagogastric junction (Figure 7-1, B). Asymptomatic Schatzki’s rings are detected in approximately 10% of the population.4 The ring is always noted in the presence of a hiatal hernia. However, most hiatal hernias are not associated with Schatzki’s rings. The etiology of a Schatzki’s ring is unknown. Because they are rarely seen in childhood and generally are first noticed in middle age, it is unlikely that a Schatzki’s ring represents a congenital abnormality. A video image of a Schatzki’s ring can be seen in Video 7-2 as a narrowing of the esophageal lumen in the distal esophagus during swallowing of a thicker bolus. Webs and rings typically produce dysphagia for solids only. Patients often report that symptoms are intermittent and less likely if they select their food wisely and chew carefully (see the section on differential diagnosis). Conversely, symptoms are more likely if the patient eats away from home or carries on a conversation while eating; in these situations the choice of food is more restricted and proper preparation of food before swallowing is more difficult. The patient often must end the episode by inducing regurgitation. Once the food is dislodged, the patient often can return to the meal without further difficulty. Treatment of webs or rings involves dilatation or rupture of the ring by any one of a variety of esophageal dilator systems. The ring is thin, nonfibrotic, and easy to dilate. Complete, or nearly complete, symptomatic relief can be anticipated. Failure to respond is unusual. Dilatation may provide permanent relief, although a large proportion of patients need periodic redilatation at variable intervals.5 Benign strictures are usually secondary to reflux-induced esophagitis, although most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) do not have esophagitis. Esophagitis refers to inflammation of the lining of the esophagus. Esophagitis may vary in severity from microscopic inflammation to mucosal edema to erosion, ulcerations, and stricture. Patients usually describe a history of heartburn or chest pain and may report the frequent use of antacids or other ulcer medications. In some patients the esophagus appears to be relatively insensitive to acid exposure. These individuals never experience significant reflux symptoms despite severe esophagitis and progression to stricture formation. Although most benign esophageal strictures are a result of reflux esophagitis, any source of esophagitis can cause stricture formation (Box 7-1). Drug-induced or pill esophagitis can be seen in young or elderly patients. Typically, commonly administered medications that are larger in size (tetracycline, potassium, quinidine) become lodged at the level of the aortic arch and dissolve, causing inflammation and stricture. Symptoms of chest pain, odynophagia, heartburn, and dysphagia may be present, usually more acutely in younger patients.6 Radiographically, a benign stricture is seen as a narrowed segment of esophageal lumen that may range from 1 cm to many centimeters long (Figure 7-2). The stricture usually is smooth and gradually tapering, with a symmetric lumen that follows the anticipated path of the normal esophagus. Ongoing inflammation may produce an eroded appearance along its course. A lateral and anteroposterior (AP) video image of a midesophageal stricture caused by GERD can be seen in Video 7-3 on the Evolve site. In the AP view barium flow is interrupted, with barium building up above the stricture. The lateral view shows a long, tapered appearance of a stricture in the esophagus. Radiographically, esophageal malignancies appear as strictures of variable length. By the time of presentation, the cancerous tumor or area is usually many centimeters long and involves the entire circumference of the esophageal lumen, producing a stricture. The typical malignant stricture is characterized by its shelflike proximal margins and irregular channel, which may diverge substantially from the anticipated course of the esophageal lumen (Figure 7-3). However, not all esophageal cancers are obviously malignant on barium radiography, and occasional malignant-looking strictures may be benign.6 For this reason, endoscopy with tissue sampling by biopsy with or without cytologic brushing is essential to differentiate benign and malignant strictures. Curative treatment is primarily surgical, although apparent cures by radiotherapy have been reported. Unfortunately, by the time symptoms develop, the cancer is usually very advanced and incurable. The overall 5-year survival rate for esophageal cancer is only approximately 5%.1 Even among those in whom resection for apparent cure is possible, the 5-year survival rate is only approximately 15%.7 Recent studies suggested that the 5-year survival rate could be doubled with a combination of preoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy.8 Surprisingly, almost 25% of patients had no evidence of cancer by gross or histologic examination. Among these patients, survival was improved fourfold over rates reported for surgery alone and twofold over those with evidence of residual tumor at surgical resection. For patients in whom curative resection is not possible, palliative resection often is still feasible and provides good symptomatic relief. In the past, a high perioperative mortality rate of approximately 29% combined with the infrequency of cure made surgery unattractive.9 However, with better nutrition provided by preoperative and perioperative hyperalimentation the risk of palliative surgery has declined.10 Although endoscopic treatment with laser, bipolar electrocautery, or stent placement may be highly successful in reestablishing luminal patency, a substantial proportion of patients with esophageal cancer have poor appetites and are unable to gain weight. The early use of endoscopically placed or fluoroscopically guided gastrostomies should be considered in patients who do not eat once the lumen is reestablished or who are scheduled to undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy, treatments that may produce or exacerbate anorexia. (See Chapter 8 for a discussion of transhiatal esophagectomy.) Esophageal spasm is a graphic term with an imprecise meaning. The diagnosis of esophageal spasm is used quite freely among physicians, including gastroenterologists. All too often esophageal spasm is diagnosed on the basis of minor degrees of dysmotility seen radiographically (Figure 7-4) or manometrically (Figure 7-5), or even on the basis of consistent symptoms in the absence of radiographic or manometric confirmation. Esophageal spasm constitutes the end of a spectrum of nonspecific esophageal dysmotility. At one end of the range are the abnormal contractions seen occasionally in normal individuals. At the other are repeated high-amplitude, prolonged, simultaneous, or multiphasic contractions or some combination of these in the absence of any normal peristaltic activity (Figures 7-5 and 7-6). Although few would argue against calling the latter spasm, little agreement exists on where less-severe abnormalities of esophageal peristalsis end and spasm begins.

Esophageal Disorders

STRUCTURAL DISORDERS

Esophageal Stenosis

Rings and Webs

Benign Stricture

Malignant Stricture

ESOPHAGEAL MOTILITY DISORDERS

Disorders of Peristalsis

Diffuse Esophageal Spasm

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Esophageal Disorders