Epidemiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence

Steven E. Swift

INTRODUCTION

The epidemiology of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse are often included together in the literature; however, these two diseases are distinct and separate entities that have only superficial similarities in their epidemiology. They are both common diseases, occurring in 5% to 30% of the population, and both can be managed surgically, often simultaneously. It has been reported that there is an incidence of 2.04 to 2.63 surgical procedures to correct prolapse or genuine stress incontinence per 1,000 women-years, with an increasing incidence as women age, and a lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for prolapse or incontinence of 5% to 11.1% (1,2). One reason these two conditions are often lumped together involves the role of pelvic floor muscle relaxation in the development of both stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. While this is true, it should be remembered that only about half of the urinary incontinence cases encountered are stress-related, and the remaining types of incontinence have little to do with pelvic floor muscle relaxation, while all of prolapse is related to pelvic floor muscle relaxation and attenuation of ligamentous structures.

DEFINITIONS

Another similarity between these two entities involves the use of condition-specific definitions in the literature. Most of the older literature concerning the epidemiology of pelvic organ prolapse used a nonspecific definition that was unique to that paper (3). Recent efforts by international organizations to standardize a definition of pelvic organ prolapse have provided some guidance but have not cleared up the situation. The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) technical bulletin defines pelvic organ prolapse as the protrusion of the pelvic organs into or out of the vaginal canal (4). The International Continence Society (ICS) defines the absence of prolapse as any subject with pelvic organ prolapse quantification system (POPQ) stage 0 support (5). Finally, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) defines pelvic organ prolapse as (POPQ) stage II, III, and IV exams (6). These definitions range from the very loose ACOG definition to the very specific but different ICS and NIH definitions. Currently there is no clinical definition of pelvic organ prolapse; however, several investigators are suggesting that prolapse of any vaginal segment beyond the hymenal remnants may be the best working definition (this includes some POPQ stage II and all stage III and IV exams).

There is less controversy regarding the definition of urinary incontinence, but here as well the epidemiologic literature is fraught with confusion. In this body of literature, while the definitions are standard and recognized, they are seldom used when querying subjects, and therefore the studies reported in the literature often have disparate findings not due to true population differences but secondary to differences in how incontinence is defined. The ICS has taken the lead in defining incontinence through their Standardization of Terminology Committee, which publishes a series of documents setting the international standards for defining lower urinary tract disorders. This committee has recently changed the definition of urinary incontinence in a subtle manner that will

likely influence future studies. The older ICS definition of urinary incontinence (in place since 1982) is involuntary loss of urine which is objectively demonstrable and is a social or hygienic problem (7). The new ICS definition of urinary incontinence (as of 2002) is the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine (8). While these changes are subtle, any studies that were based on responses using a questionnaire employing the older definition may vary from responses using a questionnaire using the newer definition.

likely influence future studies. The older ICS definition of urinary incontinence (in place since 1982) is involuntary loss of urine which is objectively demonstrable and is a social or hygienic problem (7). The new ICS definition of urinary incontinence (as of 2002) is the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine (8). While these changes are subtle, any studies that were based on responses using a questionnaire employing the older definition may vary from responses using a questionnaire using the newer definition.

Another problem in studying urinary incontinence is that there are various forms or types of urinary incontinence that probably have very different etiologies. Stress urinary incontinence is generally thought to be due to a defective urethral sphincter mechanism arising from damage to the pudendal nerve and fascia of the pelvis as a result of childbirth. Urge urinary incontinence is due to uninhibited detrusor contractions that may have a subtle or overt neurologic etiology. Mixed incontinence is a combination of both and may be due to multiple factors. These types of incontinence, along with rarer forms such as overflow incontinence and fistulas, cannot be easily distinguished based on history and physical examination and may require complex urodynamic testing (9). Therefore, any epidemiologic study findings based solely on responses to a questionnaire would be suspect in identifying specific etiologies for the various types of incontinence.

Despite these limitations, the literature in this area is growing and we are beginning to understand and appreciate the epidemiology of these disorders. This will eventually allow us to recommend prevention strategies. A corollary to this developing body of epidemiologic literature is the development of questionnaires specifically designed to identify these conditions in large general populations (10). These will allow us to perform population-based studies and will help settle some old controversies based on conflicting reports.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

Incidence of Pelvic Organ Support Defects

Determining the difference between normal and abnormal pelvic organ prolapse is complicated, not only because we lack a validated definition, but also because there is a lack of knowledge regarding the distribution of pelvic organ support in the normal female population. It can be difficult to define something as pathologic without some understanding of normal, particularly in the patient who is asymptomatic. Therefore, prior to describing the etiology of pelvic organ prolapse, a discussion on the state of our current understanding regarding the distribution of pelvic organ support in the female population is in order.

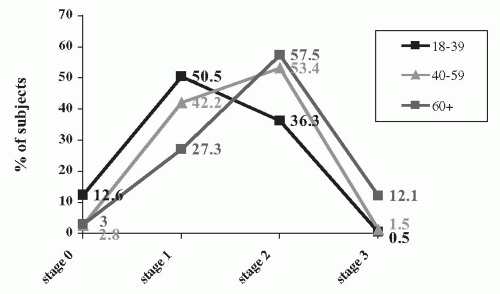

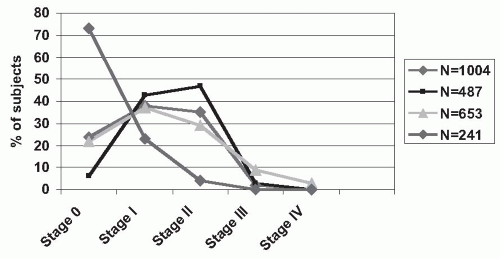

Several reports have described the distribution of pelvic organ support in female populations employing the POPQ exam to define the degree of pelvic organ support in their subjects (11, 12, 13, 14). The POPQ is a classification system for documenting the degree of pelvic organ support that describes five stages (0 through IV), with stage 0 representing excellent support and stage IV representing complete vaginal vault eversion or complete uterine procidentia. This classification system has been found to be a reliable and reproducible tool for quantifying pelvic organ support (15,16). Three of the four large studies to date had similar findings, with the majority of subjects examined having POPQ stage I or II exams and only 3% to 9% having stage III and IV exams. The distribution of POPQ stages demonstrates a bell curve distribution (Fig. 2.1). Two of these studies (11,13) represent patients presenting to outpatient gynecology clinics for annual Pap smears and pelvic exams. The other (12) was a true population-based study of women living in a Danish city. The one outlying study was done on a group of perimenopausal women presenting for a study on soy supplements to treat menopausal symptoms (14). The drawback to all of these reports is that the populations studied may not necessarily be reflective of the general female population. However, despite being different populations, three of the four studies have strikingly similar results, suggesting that most women will have stage I or II exams and that only 3% to 11% will have advanced degrees of prolapse.

Etiology of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Increasing parity and advancing age are consistently identified as risk factors for the development of pelvic organ prolapse. Several other factors have also been implicated: vaginal versus abdominal delivery of a term infant, antecedent surgery to correct prolapse, hysterectomy, congenital defects, race, lifestyle, and chronic disease states that increase intra-abdominal pressure (i.e., chronic constipation, pulmonary disease, obesity). However, here the literature is not as consistent, and the role that these factors play is still not fully understood.

Childbirth

Vaginal delivery of a term infant has been postulated to be the most significant contributor to the

subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (1,2,11, 12, 13,17,18). It is postulated that as the fetal vertex passes through the vaginal canal, it stretches the levator ani muscles and the pudendal nerve, leading to damage with permanent neuropathy and muscle weakness. This damage is felt to be ultimately responsible for pelvic organ prolapse noted later in life.

subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse (1,2,11, 12, 13,17,18). It is postulated that as the fetal vertex passes through the vaginal canal, it stretches the levator ani muscles and the pudendal nerve, leading to damage with permanent neuropathy and muscle weakness. This damage is felt to be ultimately responsible for pelvic organ prolapse noted later in life.

FIGURE 2.1 ● Percent of subjects in each POPQ stage from four population-based studies. (N, the number of subjects examined in each study.) |

If stretching of the pelvic floor plays a significant role in the development of pelvic organ prolapse, then larger infants should exacerbate this damage, and this should be reflected in the etiology of prolapse. When this was specifically addressed, it was reported that there is a 10% increase in the association of pelvic organ prolapse with each 10- to 16-ounce increase in the birthweight of a vaginally delivered infant (13,18).

Also, it would be expected that the birth route would play a role in the subsequent development of prolapse. It has been demonstrated that the pudendal nerve damage caused by vaginal delivery can be avoided by cesarean section (19, 20, 21). However, several recent articles have demonstrated conflicting results when evaluating the risk of a vaginal over cesarean delivery on the eventual development of pelvic organ prolapse (13,22). Therefore, it remains unclear whether it is the pregnancy or the delivery route that places an individual at risk for prolapse.

Age

Another area where the literature is in agreement involves the increasing prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse in a population as it ages (2,11,12, 13,17,18,22,23). This is intuitive to the clinician, as there are very few patients in their twenties and thirties with significant pelvic organ prolapse. Figure 2.2 demonstrates the distribution of pelvic organ support as women age. The peak or median POPQ stage of support shifts to the right as the population described increases in age. It has been shown that there is roughly a 30% to 50% increase in the incidence of pelvic organ prolapse with each 10 years of advancing age (13,17,18). This confirms data on the incidence of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse from several studies that showed a 50% to 100% increase per decade in the incidence of surgery to correct pelvic organ prolapse up until age 70, where it appears to plateau (2,23).

Menopause

The literature is consistent that the risk of pelvic organ prolapse increases with advancing age, but what role menopause and hormone replacement therapy have on pelvic organ prolapse is unknown. One study has identified menopausal status as a risk factor to develop prolapse (17). However, they did not determine which patients were taking hormone replacement therapy and which were not. In other studies, menopausal status and whether or not a subject was taking hormone replacement therapy were not identified as risk factors for developing pelvic organ prolapse (13,18). Therefore, it may be that advancing age is more responsible for the increased risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse than is menopausal status. Currently, the role of estrogen in the area of pelvic organ support is unclear, but while it may not prevent the development of prolapse it probably does not promote its development, and its use in subjects with significant pelvic organ support defects should be viewed as neutral. Whether or not it can prevent or delay the onset of pelvic organ prolapse remains to be determined.

Previous Surgery to Correct Pelvic Organ Support Defects

This may not be a fair addition to the etiologies of pelvic organ prolapse, as these subjects already have manifested pelvic organ support defects and have the underlying pathologic processes that lead to this disease. Recurrence rates for surgical correction of pelvic organ prolapse are in the 10% to 30% range (2,24,25). Therefore, it is not surprising that when subjects identified with previous surgery to correct prolapse are included in studies, this is consistently identified as a risk factor. When the various risk factors for developing severe (POPQ stage 3 and 4) pelvic organ prolapse were analyzed, it was determined that previous surgery to correct prolapse was the single greatest risk factor for the subsequent development of severe prolapse (18). This appears to be a statement on the inadequacies of our current surgical procedures for correcting significant pelvic organ prolapse.

Hysterectomy

The role of hysterectomy as a cause of subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse is controversial, with no current consensus. The overall incidence of severe pelvic organ prolapse following hysterectomy has been estimated to be 2 to 3.6 per 1,000 women-years (26,27). This is similar to the rates of surgically corrected pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence noted for the general population (2.04 to 2.63 per 1,000 women-years) and would suggest that there is no excess of pelvic organ prolapse in subjects with a prior hysterectomy (1,2). When the role of hysterectomy was specifically addressed, the results are mixed, with some studies identifying it as a risk factor for prolapse and others suggesting it is not (1,13,18). The next question regarding hysterectomy is whether the route of surgery influences the subsequent development of pelvic support defects. The general opinion is that the incidence of pelvic support defects is greater following a vaginal hysterectomy than an abdominal hysterectomy (11,13,26,28). However, the rates and degree of prolapse appear similar regardless of the type of antecedent hysterectomy (1,26). While the route of hysterectomy may not predict subsequent development of pelvic organ prolapse, there is a correlation between subsequent prolapse and the initial indication for the hysterectomy. Pelvic organ prolapse rates as high as 15 per 1,000 women-years have been noted in patients whose indication for hysterectomy was uterine prolapse (2). This confirms the above findings of an increased risk of pelvic organ prolapse following surgery to correct pelvic support defects and may explain some of the data suggesting vaginal hysterectomy as a cause of pelvic organ prolapse.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree