During the past decade, the increasing number of recognized cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults has resulted in a dramatic expansion of the medical literature surrounding it. Clinical and basic research has contributed to a better, but still incomplete, body of knowledge regarding its clinical and histologic manifestations, as well as its immunologic and genetic pathogenesis. This article provides a broad framework for recognizing the remarkable variety of clinical manifestations of eosinophilic esophagitis in children, which must be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in many different clinical situations.

During the past decade, the increasing number of recognized cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults has resulted in a dramatic expansion of the medical literature surrounding it. Clinical and basic research has contributed to a better, but still incomplete, body of knowledge regarding its clinical and histologic manifestations, as well as its immunologic and genetic pathogenesis.

This article provides a broad framework for recognizing the remarkable variety of clinical manifestations of eosinophilic esophagitis in children. There is not a convenient “one size fits all” description of the presentation of eosinophilic esophagitis, and therefore physicians must consider it as part of the differential diagnosis in many different clinical situations. Prompt, accurate diagnosis is required for timely management, symptom control, and prevention of untoward sequelae from the disorder.

Much of the medical literature related to eosinophilic esophagitis exists as case reports, case series, and reviews from centers in North America. The larger case series form the basis for the current understanding of the clinical manifestations of eosinophilic esophagitis in children and come from the tertiary referral centers that focus on diagnosis and management of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis . In addition, the recent publication of diagnostic guidelines will allow standardization for clinical care and future research studies .

Although most of these works were not designed primarily as epidemiologic studies, the demographics of the identified patients support several common findings. For reasons that remain unclear, approximately 70% of children who have eosinophilic esophagitis are males. A series in the United States also has confirmed the clinical impression that the majority (94.4%) of patients are white .

In southwest Ohio, the incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in children has been estimated at 1.25 cases per 10,000 children per year . Formal epidemiologic studies encompassing the broader population are needed to understand more precisely the risk for developing eosinophilic esophagitis in North America and abroad.

Symptoms of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

The most frequent symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis are nonspecific and include dysphagia, pain, and vomiting. The age at which the symptoms develop varies considerably . Feeding difficulty was the predominant reason for referral and evaluation of infants and toddlers ultimately diagnosed as having eosinophilic esophagitis. Preschool and school-aged children commonly complained of abdominal pain or vomiting, whereas dysphagia generally appeared as a primary complaint in the preadolescent years. In that analysis the chief complaint was recorded, but most patients had more than one symptom attributable to the disorder.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia caused by eosinophilic esophagitis is described variously by affected individuals and is notoriously intermittent. Age and ability to communicate effectively influence how a child describes his or her own difficulty swallowing. Some note that food “goes down slowly,” whereas others say that food gets stuck temporarily somewhere in the throat or chest before proceeding down. Some report difficulty initiating the swallow while the bolus is still in the mouth or recognize anxiety promoted by prior episodes of food impaction. Retrospective analyses note that dysphagia was present for more than 2 years before diagnosis in some patients . As detailed in the article by Katzka, elsewhere in this issue, dysphagia has been the predominant presenting symptom in adults.

A careful history in patients who complain of dysphagia reveals that they have learned to compensate by eating slowly, drinking after each bite, taking small bites, chewing excessively, or avoiding specific food consistencies that are problematic such as meat or bread. This phenomenon may help to explain the intermittent experience of dysphagia, because the failure to compensate at a particular meal or even for a single bite may allow the symptom to manifest and “reset” the compensatory mechanisms.

Food impaction requiring endoscopic removal as the initial contact between an adolescent and the medical community is a fairly common presentation for eosinophilic esophagitis. Often the dysphagia has been long standing but mild and intermittent. Many individuals report years of symptoms that were ignored, compensated for, attributed to “taking too big a bite”, or that were blamed on “not chewing food well enough.”

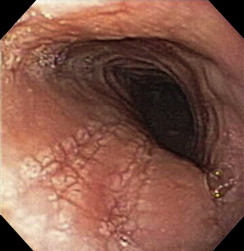

The author and colleagues also have diagnosed eosinophilic esophagitis when called to remove from the esophagus impacted but nonobstructing foreign bodies that normally would have passed, such as coins. It is good practice to obtain mucosal biopsies from the esophagus, remote from the site of the impaction, after endoscopic removal of a foreign body, especially food impactions. Endoscopic evidence for eosinophilic esophagitis (thickening, furrowing, or pinpoint or diffuse white exudate) ( Figs. 1 and 2 ) is frequently present in affected individuals at the time of the impaction, but because the endoscopic appearance may be influenced by the foreign body on the one hand, and because up to one third of patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis may have a normal-appearing esophagus at endoscopy on the other hand , mucosal biopsy is warranted after extracting a foreign body in children.

Less common but clearly problematic, gastroenterologic consultation has been requested for some individuals after long periods of psychiatric evaluation and treatment of chronic dysphagia without radiographic evidence for dysmotility or stricture. The authors have seen children ultimately proved to have eosinophilic esophagitis whose dysphagia has been attributed to underlying anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder. One boy was diagnosed with bulimia at age 10 years because he vomited after eating, although he had symptoms since infancy.

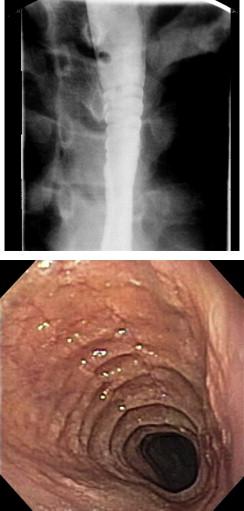

Dysphagia in patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis can be caused by mechanical obstruction of the esophagus and can manifest endoscopically and/or radiographically as a ring ( Fig. 3 ) focal stricture, Schatzki ring, or long-segment narrowing (so-called “small-caliber esophagus”) . It is more common, however, for children to complain of dysphagia in the absence of radiographic narrowing of the esophagus . Nurko and colleagues examined the esophageal histology proximal to radiographically diagnosed Schatzki rings in 18 children and discovered that eosinophilic esophagitis was present in 8 of them. Notably, endoscopic evidence for Schatzki ring was not present in the children who had histologic eosinophilic esophagitis, suggesting that focal transient spasm accounted for the radiographic finding.

It is tempting to attribute dysphagia to the degree of inflammation, duration of disease, degree of lamina propria fibrosis, or the impact of chronic inflammation on deeper layers of the esophagus. The deep layers of the esophagus are affected, as evidenced by the thickening of the entire wall of the esophagus demonstrated by endoscopic ultrasound . Nonspecific manometric abnormalities were observed in 60% of studied adult patients who had eosinophilic esophagitis . In that study, parallel improvement in manometric and histologic findings was observed.

It is tempting to speculate that adolescents and adults who have had long-standing untreated disease develop dysphagia as a consequence of persistent inflammation-induced damage including lamina propria fibrosis or remodeling, but because the age of disease onset often is unknown in that group, it has not been possible to associate dysphagia directly with the duration of inflammation in many individuals .

Stricture is a feared complication of eosinophilic esophagitis and has been described as early as 7 months of age . Although the strictures are amenable to dilatation, esophageal mucosa with eosinophilic inflammation is more prone to tear during dilatation than the mucosa overlying a peptic stricture, and perforation of the esophagus has been described as a complication of attempted dilatation in adults . Many clinicians managing adults who have eosinophilic esophagitis–associated dysphagia now recommend aggressive medical management of the inflammation before attempting dilatation unless clinical circumstances dictate more immediate relief of the obstruction . Prospective study has not confirmed that this approach reduces the number of dilatations or the risk of perforation, but this approach is reasonable until refuted. Similarly, dogmatic historical concepts generated by experience in dilating peptic strictures should be abandoned and replaced by recommendations for gentle, gradual dilatation only when necessitated by failure of medical therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Infants and preverbal toddlers who have eosinophilic esophagitis may present with feeding difficulties that manifest as gagging, choking, food refusal/aversion, or vomiting . It is not well understood whether these problems are consequences of dysphagia, nausea, anorexia, pain, fear or anxiety after untoward experiences with eating, or a combination of these factors. Clinicians participating in the evaluation of young children who have feeding disorders must be knowledgeable in the evaluation and treatment options for eosinophilic esophagitis and have a low threshold for early evaluation and intervention. Because there are overlapping issues, concurrent therapy to account for all of the child’s conditions (gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], behavioral feeding aversion, and eosinophilic esophagitis) may be necessary.

Vomiting

Vomiting as a primary complaint among pediatric patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis occurs most often in young children. It can mimic reflux, manifest as effortless regurgitation, but eosinophilic esophagitis is seldom diagnosed in the first 6 months of life when GERD is common. Accurate diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis in very young children who vomit is often delayed by months to years, during which time treatment for symptoms attributed to GERD is attempted. In the author’s experience, parents describe vomiting more often than effortless regurgitation.

Circumstances surrounding episodes of vomiting vary. Vomiting can be part of an overt and immediate allergic response to a recently ingested food. In that case, the family generally recognizes that there is a consistent reaction to that food and chooses to avoid it. Immediate vomiting may be associated with other manifestations of an adverse immune response such as hives, diarrhea, pain, or even anaphylaxis. Some children who have eosinophilic esophagitis and multiple food allergies have a history of developing different constellations of symptoms in response to various foods, up to and including food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome.

Chronic, episodic, unpredictable vomiting of variable severity also occurs in patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis, and it is not clinically distinguishable from other causes of emesis. This vomiting does not occur proximate to exposure to a particular food, which precludes devising an appropriate diet based solely on history.

In the first year of life, clues that eosinophilic esophagitis, rather than reflux, is the underlying culprit include early onset of vomiting (within days to weeks of birth) associated with eczema, vomiting associated with irritability that does not respond to acid suppression, and onset of vomiting in the second half of the first year of life during the introduction of solid foods.

After infancy, vomiting is more chronic, intermittent, and not readily associated with particular foods, although it is usually meal related. Vomiting to the point of excess calorie loss resulting in failure to gain weight or weight loss is possible but uncommon.

Rarely, nausea without vomiting is the sole presenting manifestation of eosinophilic esophagitis. Although usually present with other symptoms, it has been an isolated complaint in a few individuals. Nausea has been responsive to standard treatment of the esophagitis in most individuals, but the author and colleagues have seen other children who have remarkably recalcitrant nausea as a persistent complaint after resolution of active eosinophilic inflammation.

Retching to remove a piece of food that is stuck may be called “vomiting” by some patients and needs to be distinguished from emesis of gastric contents. Retching can be recognized as such by careful history. The patient will report that something got stuck and he or she retched to remove or otherwise dislodge it.

Pain

Pain is a frequent but not universal complaint among individuals who have untreated eosinophilic esophagitis. Children who have pain associated with eosinophilic esophagitis report chest, epigastric, and/or abdominal pain. Overt odynophagia is not typical. Some individuals have been evaluated the emergency department for episodic crushing substernal pain concerning for heart disease. Those individuals have been remarkably free of symptoms between pain attacks, which have been unpredictable in frequency and which lack an obvious inciting event.

The pain may be described as heartburn and may respond to acid suppression. When histologic eosinophilic inflammation persists despite effective therapy for GERD, a clinical diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis is established.

A remarkable number of children indicate that their pain is in the epigastrium or the periumbilical area. They often have difficulty describing the pain in more sophisticated terms. It is imperative that these complaints promote appropriate investigation, particularly when the broader clinical picture is concerning, such as a boy who has asthma or eczema or a history of food allergy. The absence of complaints referable to the chest should not preclude consideration of esophageal disease.

Associated Conditions

Communicative children who have eosinophilic esophagitis may present with a single symptom, but careful questioning often elicits additional symptoms that are attributable to the inflammation. In addition, many children who have eosinophilic esophagitis have other medical conditions with symptoms that may overlap, contribute to, or serve to confuse the issue at presentation. For example, chest pain may accompany episodes of bronchospasm in a child who has asthma, and that phenomenon may divert attention away from other potential causes of chest pain, such as esophagitis (reflux or otherwise).

The profile of individuals who have eosinophilic esophagitis is quite varied, but there are notable associations. Because definitions and rigor in establishing a formal diagnosis vary, the precise frequency of associated conditions is subject to interpretation. Nevertheless, eosinophilic esophagitis coexists or is a parallel phenomenon associated with asthma, eczema, and environmental and food allergies in up to 75% of children .

The association of eosinophilic esophagitis with other conditions is becoming more apparent from experience. The epidemiology and immunobiology are as yet unexplored. For example, esophageal eosinophilia has been seen in the Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders in a handful of children who have other gastrointestinal conditions such as Helicobacter pylori gastritis, Crohn’s disease, or celiac disease.

Esophageal involvement can be seen in patients who have eosinophilic gastroenteritis. It is inappropriate to make a clinical diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis when substantial eosinophilic inflammation of stomach, small intestinal, or colon is present concurrently or sporadically in a patient who has had eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus. Studies have examined the number of eosinophils in normal gastrointestinal mucosa, but formal histologic and clinical definitions of eosinophilic gastroenteritis are yet to be developed . As such, separating patients who have eosinophilic esophagitis who happen to have mild and clinically irrelevant mucosal eosinophilia distal to the esophagus from cases of eosinophilic gastroenteritis with esophageal involvement can be challenging. Diarrhea, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, failure to thrive, and gastrointestinal bleeding are not typical features of isolated eosinophilic esophagitis, and individuals who display them should be evaluated appropriately, even if a provisional diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis has been made.

A number of children who have underlying neurologic or neurodevelopmental conditions have been diagnosed as having eosinophilic esophagitis. Eosinophilic esophagitis has been seen in children who also have intractable seizures, cerebral palsy, Chiari malformation, pervasive developmental disorder, sensory integration disorder, or migraine. Hypersensitivity to antiepileptic drugs has been implicated in the development of eosinophilic esophagitis, so it is important to account for medication use in this group . Otherwise, no obvious, direct, cause-and-effect relationship between these neurologic conditions and eosinophilic esophagitis has been discerned to date.

The epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis in children who have concurrent neurodevelopmental conditions has not been explored formally. It is not clear whether the prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis is indeed higher in that population of children or whether clinicians have become more thorough in evaluating them. GERD is said to occur frequently in this population as well, but it is no longer safe to assume that GERD is responsible for nonspecific upper gastrointestinal symptoms.

Similarly, eosinophilic esophagitis has been discovered in children who have other syndromes, without comment on the epidemiology. A case report notes the association of eosinophilic esophagitis in Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome . The author and colleagues have seen eosinophilic esophagitis in children who have coloboma, heart anomalies, choanal atresia, retardation of growth and development, and genital and ear anomalies (CHARGE syndrome), vertebral, anal, tracheo-esophageal, and radial limb or renal anomalies (VATER syndrome), Pierre-Robin syndrome, Klinefelter’s syndrome, Moebius syndrome, and Pfeiffer syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree