Enucleation of Hepatic Lesions

Florencia G. Que

Mark D. Sawyer

Introduction

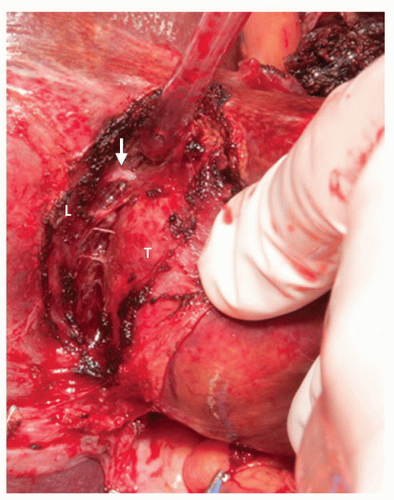

Enucleation is a useful parenchymal-sparring technique for the treatment of many hepatic lesions. While mostly suited to benign lesions such as adenomas and symptomatic hemangiomas, enucleation may be useful in situations where debulking of malignant disease is indicated clinically, such as ovarian and neuroendocrine metastases. The operative techniques are generally straightforward, and lesions near the hepatic surface may lend themselves well to laparoscopic techniques. Enucleation may be used in combination with resection and/or radiofrequency or microwave ablation. As the tumors amenable to enucleation are by their nature not invasive, anatomic structures are usually displaced rather than invaded making it possible to remove large masses (see Fig. 25.1); and in the case of neuroendocrine metastases, large total numbers of tumors may be present with a relatively small impact on hepatic anatomy and functional hepatic mass.

Selection of Candidates

The lesions usually amenable to enucleation are hemangiomas, cystadenomas (provided that the presence of malignant change can be reliably excluded, see Chapter 28), hepatic adenomas and focal nodular hyperplasia, simple and hydatid cysts, and neuroendocrine metastases. Patient selection should also take into consideration whether or not an anatomic resection (see Chapter 18) or nonresectional technique, such as ablation, may provide equivalent results with lower morbidity than enucleation.

A distinct advantage of enucleation is that it may be employed when anatomic lesions abut major vascular and ductal structures, such as in the case of a centrally located hemangioma. While radiofrequency ablation may be used near major vascular structures, it generally should not be used within a centimeter of major ductal structures due to the elevated risk of bile duct injury.

Metastatic neuroendocrine lesions are often good candidates for treatment by enucleation whether as the solitary technique employed or in conjunction with anatomical resection or ablative techniques. As the goal in such cases is often debulking rather than

a curative resection, a flexible, varied, and multifaceted approach will often yield the best results.

a curative resection, a flexible, varied, and multifaceted approach will often yield the best results.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUESGeneral

Operative technique in enucleation has four main elements: division of overlying hepatic parenchyma (approach), separation of the lesion from the surrounding rim of compressed hepatic tissue, division of the small vessels that feed and drain the lesions, and hemostasis.

Optimal approach generally entails division of the hepatic parenchyma overlying the lesion at its most superficial point, although, in the case of more deeply seated lesions, a pathway along the interlobar or intersegmental planes will entail less perturbation of surrounding hepatic anatomic structure and less attendant risk of bleeding or biliary leak (see Fig. 25.2). The hepatotomy should be of sufficient length to allow adequate exposure to circumferentially to separate the lesion from the surrounding hepatic tissue, and safely ligate and divide bridging vessels.

The technique of separating the lesion from the surrounding hepatic parenchyma is similar regardless of the underlying lesion, and a number of techniques may be used depending upon surgeon preference (see Chapter 18). In the hands of a surgeon comfortable with a particular technique, Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA), finger fracture, electrocautery, and water jet dissection all accomplish the purpose of separating the lesion from the surrounding hepatic parenchyma with similar results; the particular technique utilized is more the function of the surgeon’s familiarity with it rather than any purported technologic superiority.

Ligation of the bridging vessels should be as meticulous as with any other hepatic resection. While vessel clips may be utilized on the lesional side, the author prefers to minimize or avoid the use of clips on the hepatic side, as they may cause artifactual interference at future radiologic imaging and may be dislodged during the resection as the lesion is retracted from one direction to another. Other alternatives are coagulative/ division devices such as the LigasureTM (Covidien, Boulder, CO) and harmonic scalpel, which coagulate and divide vessels up to 7 mm. While the underlying physics of the two devices are disparate—the harmonic scalpel simultaneously coagulates and divides tissue with harmonic vibrations at 20,000 Hz, and the LigasureTM is essentially a bipolar cautery device which coagulates, then divides—the vessel size they are capable of dividing safely and effectively (and therefore the end result) is essentially the same.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree