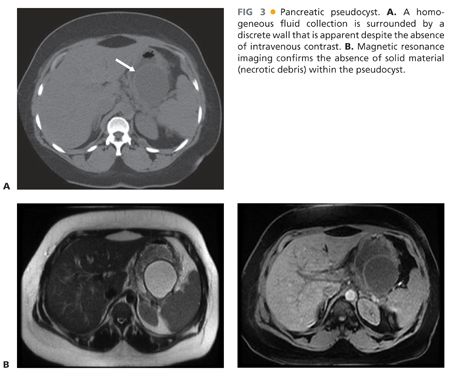

■ APFCs that fail to resolve may become pancreatic pseudocysts with well-defined walls. Pancreatic pseudocysts (FIG 3A) are encapsulated, well-defined peripancreatic or intrapancreatic fluid collections that arise from focal disruption of the pancreatic ductal system in the setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis or trauma. In contrast to cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, pseudocysts lack true epithelial walls and instead have walls composed of fibrous tissue containing histiocytes, giant cells, granulation tissue, and rarely eosinophils. The fluid within a pseudocyst is characteristically amylase rich as it arises from disruption of the pancreatic ductal system. The 2012 revision of the Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis also emphasizes that pseudocysts are not associated with detectable amounts of pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis and do not contain a solid component. Magnetic resonance imaging (FIG 3B) or ultrasound may be useful for identification of solid material not distinguishable on computed tomography.

■ In contrast to APFCs and pancreatic pseudocysts, acute necrotizing pancreatitis is defined by the presence of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic tissue necrosis. In the early stages of acute necrotizing pancreatitis, the necrotic tissue is described as an acute necrotic collection (ANC) (FIG 4). Such collections may additionally contain fluid leaking from the pancreatic duct or resulting from liquefaction of necrotic tissue. The natural history of ANCs is variable. Such collections may persist or absorb, remain solid or liquefy, remain sterile or become infected.

■ Fibrous walls form around necrotic collections that are not reabsorbed or do not require early surgical debridement. As with acute necrotic collections, areas of walled-off necrosis (WON) (FIG 5) may contain fluid in addition to solid material.

■ Although the pathogenesis and contents of WON differ from pancreatic pseudocysts, their management is similar to pseudocysts, particularly if communication with the pancreatic ductal system is suspected.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

■ Pancreatic pseudocyst

■ Walled-off necrosis

■ Pancreatic cystic neoplasms possess a true epithelial lining and thereby differ from pseudocysts that are lined by fibrous tissue (see earlier discussion). Cystic neoplasms primarily fall into two categories. Microcystic cystadenomas contain serous fluid and carry minimal if any risk of malignant transformation. Treatment by means of surgical resection is reserved for those that are symptomatic. Macrocystic cystadenomas contain mucinous material, are characterized by the presence of ovarian stroma, and have the potential for malignant transformation. Surgical resection is therefore usually recommended for such lesions.

■ Neoplasms with cystic morphology. Adenocarcinomas of the pancreas may have cystic components. Areas of tumor necrosis, for example, may liquefy and appear cystic on imaging studies. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas may also cause proximal ductal obstruction that may resemble cysts in the pancreas. Pancreatic endocrine tumors may also occasionally be predominantly cystic.

■ Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms may arise in the main pancreatic duct or in side branch ducts and on imaging appear as solitary or multiple pancreatic cysts.

■ Other benign cystic abnormalities include lymphoepithelial cysts and inclusion cysts. If diagnosed, treatment is reserved for those that are symptomatic. Mucinous cysts that do not contain ovarian stroma and do not appear to have potential for malignant transformation may also occur in the pancreas. Differentiation of such benign mucinous cysts from mucinous cystadenomas may be difficult.

EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

■ A thorough medical history must be taken to confirm a history of acute pancreatitis, or less commonly, pancreatic trauma. In the absence of such a history, the diagnosis of a pancreatic pseudocyst should be questioned, and the diagnosis of a neoplasm should be considered. As several weeks are required for a pseudocyst to form, the diagnosis of a pseudocyst should also be questioned if the clinical history of acute pancreatitis or pancreatic trauma is very recent and a cystic abnormality with an already well-formed wall is seen.

■ The history should also attempt to identify the etiology of the patient’s pancreatitis, as treatment of the etiology (e.g., cholecystectomy, lipid- and triglyceride-lowering medications, abstinence from alcohol consumption) should be considered.

■ Symptoms potentially attributable to a pseudocyst should be elicited. Most frequently, these will include abdominal or back pain, abdominal pressure or fullness, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, or obstructive symptoms. If a complication of the pseudocyst such as infection, bleeding, or rupture has occurred, symptoms relating to the complication such as fever, light-headedness, or diffuse abdominal pain may also be present.

■ The general medical history and overall health of the patient are important in determining the manner of treatment appropriate for the patient. Past surgical history should be reviewed with particular emphasis on prior operations on the stomach or small intestine and incisions that may impact on laparoscopic or open access to the abdomen.

■ An abdominal mass or fullness should be sought on physical exam, and if found, its location should be noted in planning subsequent surgical procedures. Abdominal surgical scars should also be noted.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

■ The presence and location of cystic changes of the pancreas are best determined by means of contrast-enhanced computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The imaging characteristics on these studies may help to differentiate among the various types of cystic pancreatic abnormalities listed earlier. Cross-sectional imaging also demonstrates the relationship of the cyst to the stomach and other structures as well as the thickness of the cyst wall and thereby aids in treatment planning.

■ Pancreatic ductal abnormalities that may influence treatment decisions can be identified by means of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP). MRCP is preferred as it is noninvasive, usually does not require patient sedation, and avoids the risks of procedure-induced pancreatitis or infection of fluid collections in communication with the pancreatic duct.

■ If the clinical history and imaging findings are not sufficient to determine the specific type of cystic abnormality and in particular to exclude the diagnosis of a neoplastic cyst with potential for malignant transformation, further imaging by means of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be performed. Under EUS guidance, fine needle aspiration of the cyst contents and cyst wall can be performed to obtain samples for biochemical and pathologic analysis. EUS can also identify solid material within the cyst and assess the thickness of the cyst wall.

■ ERP is not routinely performed for evaluation of pseudocysts, but in selected cases may be performed to evaluate ductal anatomy when MRCP cannot be performed or is inconclusive. Because of the potential for introducing infection into a sterile pseudocyst, ERP should be limited to patients selected for treatment (see the following text) and should be performed shortly before treatment.

■ Although the pathogenesis and pathology of pancreatic pseudocysts and WON differ, their management is similar and therefore differentiating between pseudocysts and WON is not always required. In the discussion that follows, the term pseudocyst is used to describe both pseudocysts and WON as defined in the 2012 revision of the Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications for Treatment

■ Treatment should be considered for symptomatic pseudocysts or enlarging pseudocysts.

■ Emergency treatment of complications such as infection, rupture, or bleeding into the pseudocyst may be required.

■ Small, asymptomatic, nonenlarging pseudocysts do not require treatment as the risk of developing acute complications is low. However, as the risk of complications arising in large asymptomatic, nonenlarging pseudocysts is uncertain and may be larger, treatment of such large pseudocysts can be considered.

■ Treatment should be considered if the diagnosis of a neoplasm with malignant potential cannot be excluded.

Treatment Options

■ Surgical resection can be performed for removal of a pseudocyst.

■ External drainage may be achieved by percutaneous or surgical means.

■ Internal drainage of a pseudocyst creates a communication between the pseudocyst and the gastrointestinal tract.

■ Drainage into the stomach is achieved by creating a communication between the posterior wall of the stomach and a pseudocyst known as a cyst gastrostomy. This may be achieved by endoscopic means, surgical means, or a hybrid combination of these methods. The anastomosis can be fashioned within the stomach via an anterior gastrotomy, outside the stomach via the lesser sac, or within the stomach via endolaparoscopic means.

■ Drainage into the small intestine is achieved by surgical creation of an anastomosis between a defunctionalized segment of the small intestine (Roux limb) and a pseudocyst known as a cyst jejunostomy.

■ Pseudocysts arising in the head of the pancreas are infrequently drained by creation of an anastomosis between the descending duodenum and the pseudocyst known as a cyst duodenostomy.

Choice of Procedure

■ Surgical resection should be considered when the diagnosis of a cystic-appearing neoplasm such as a mucinous cystadenoma cannot be excluded or selectively by means of a distal (left) pancreatectomy for a pseudocyst or WON involving the tail of the pancreas. Distal (left) pancreatectomy is discussed elsewhere in this text. Because of the greater morbidity and mortality of a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure), resection should not be considered for pseudocysts in the head of the pancreas.

■

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree