Distal Pancreatectomy—Open

Jordan Winter

Peter J. Allen

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONSDistal pancreatectomy, as referred to in this chapter, involves resection of the pancreas to the left of the superior mesenteric vasculature. The parenchymal margin of resection generally occurs at the level of the superior mesenteric vessels; however, when the target lesion is located in the very tail of the gland parenchymal transection may occur to the left of these vessels. When the lesion to be resected involves the pancreatic neck or body an extended resection may be performed and the parenchymal margin in this setting may be to the right of the mesenteric vessels. Regardless of the exact location of parenchymal transection, distal pancreatectomy implies that the duodenum and bile duct are not included in the resection. Splenectomy may or may not be performed.

The indications for distal pancreatectomy include both non-neoplastic and neoplastic processes. Non-neoplastic indications include focal chronic pancreatitis of the body or tail, left-sided pancreatic pseudocysts, and trauma to the distal pancreas. Neoplastic indications include benign and malignant tumors. The most common examples are ductal adenocarcinoma, intra-ductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and neuroendocrine tumors.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNINGPreoperative evaluation begins with the patient history and physical examination, with a particular focus on past medical and cancer history, familial cancer history, and the patients presenting signs and symptoms. Weight loss, abdominal pain, back pain, and new-onset diabetes are associated with a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. Biochemical tests include liver enzymes, serum amylase, and CA 19-9. The latter test is a biochemical marker that is frequently elevated in advanced malignancy of the pancreas, and serves as a useful marker of disease recurrence after resection.

Pancreatic lesions should be evaluated preoperatively with high-quality contrast enhanced CT or MR imaging. Multidetector CT imaging using narrow collimation and precise acquisition timing during the arterial, pancreas parenchymal, and venous phases

is an excellent technique for defining the nature of pancreatic lesions, their relationship to the peri-pancreatic vasculature, and whether there is concern for extra-pancreatic spread in the case of malignancy. Water is used as an oral contrast agent since visualization of the duodenum and small bowel is excellent and there is minimal interference with the peri-pancreatic vessels. Sagittal and coronal reconstructions are routinely performed at our institution. Triple-phase imaging allows for careful assessment of major visceral vessel involvement by the tumor and allows further characterization of the pancreatic mass. When there is suspicion for malignancy additional cuts through the chest and pelvis are also obtained.

is an excellent technique for defining the nature of pancreatic lesions, their relationship to the peri-pancreatic vasculature, and whether there is concern for extra-pancreatic spread in the case of malignancy. Water is used as an oral contrast agent since visualization of the duodenum and small bowel is excellent and there is minimal interference with the peri-pancreatic vessels. Sagittal and coronal reconstructions are routinely performed at our institution. Triple-phase imaging allows for careful assessment of major visceral vessel involvement by the tumor and allows further characterization of the pancreatic mass. When there is suspicion for malignancy additional cuts through the chest and pelvis are also obtained.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with or without fine needle aspiration should be considered when the findings would influence patient management. Indications for EUS include the need for tissue diagnosis prior to neoadjuvant therapy, the desire to further characterize an asymptomatic pancreatic cyst and to obtain cyst fluid for biochemical analysis, and in any other scenario in which non-operative management of a lesion may be possible if tissue is obtained. This latter scenario often arises in the setting of focal pancreatitis in the tail of the gland. EUS may be helpful in this situation to ensure that no underlying mass is present. Core biopsy can be performed in the tail of the gland by EUS and when pancreatitis is present IgG4 staining should be considered to evaluate for lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis.

Although endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) has an important role for patients with proximal pancreatic lesions, this is not usually the case for distal lesions. Diagnostic ERCP is seldom useful in evaluating distal lesions due to the risk of acute pancreatitis, and the ability to obtain high-quality imaging of the ductal system and pancreatic parenchyma with cross-sectional imaging. MRCP may be a useful alternative to ERCP when definition of ductal anatomy is desired.

After the patient has been deemed a surgical candidate from a medical standpoint and resection is indicated from an oncologic perspective, informed consent for a distal pancreatectomy with or without splenectomy is obtained and resection is scheduled. We do not routinely perform mechanical bowel preparation unless a synchronous colon resection is planned as prospective data have not found this to reduce postoperative infection.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE—DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY AND SPLENECTOMY

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE—DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY AND SPLENECTOMYPrior to skin incision prophylactic antibiotics are administered intravenously and the abdomen is prepared with ChloroPrep® (CareFusion, Kansas, USA) from the level of the nipples down to the pubic symphysis. The operative field is squared off with towels and the remainder of the body is covered with sterile drapes. When pancreatic cancer is confirmed or suspected, an exploratory laparoscopy is generally performed to assess for metastatic disease. This can be performed in the same setting as the planned distal pancreatectomy or as a separate stage of a two-staged procedure. Laparoscopy is typically performed by utilizing a 10 mm Hasson port placed above the umbilicus or in the left upper quadrant. One or two additional 5 mm ports are added as needed to retract, perform biopsies, and do peritoneal washings.

The decision to create either a midline or subcostal incision is based on the patient’s body habitus, the location of the tumor, and the surgeon preference. Midline incisions are considered for the thin patient, in the setting of a prior midline laparotomy, when access to another quadrant of the abdomen is necessary, or for the patient with an acutely angled costal margin. In obese patients, patients with a low xiphoid process, and when the tumor is located in the very tail of the pancreas, a left subcostal incision is generally utilized in order to maximize exposure to the left upper quadrant. After entering the abdomen, a self-retaining retractor system is set up such as the BookwalterTM (Codman, Massachusetts, USA). Cephalad retraction of the costal margin is paramount. Exploration is completed to rule out metastatic disease (initiated laparoscopically), and this involves

careful inspection of the small intestine, the liver, the pelvis, the root of the transverse mesocolon, and the peritoneal surfaces of the abdominal wall and diaphragm.

careful inspection of the small intestine, the liver, the pelvis, the root of the transverse mesocolon, and the peritoneal surfaces of the abdominal wall and diaphragm.

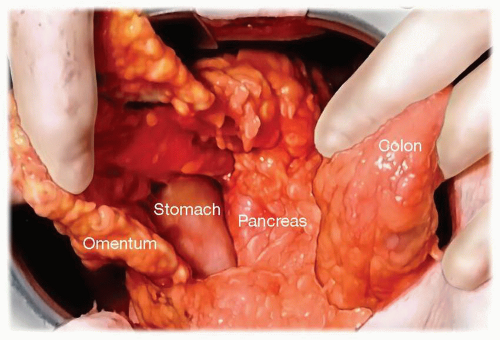

The initial step to the operation involves entering the lesser sac along the transverse colon and then dissecting the greater omentum off of the transverse colon to the splenic flexure (Fig. 3.1). The right gastroepiploic vessels and greater omentum are preserved. While many start the dissection by incising the peritoneum superior and inferior to the pancreas, we prefer to address the gland after having completely exposed the distal portion of the pancreas. Initial division of all short gastric vessels is performed so that the stomach can be retracted out of the operative field superiorly and into the right upper quadrant (Fig. 3.2). The transverse colon and splenic flexure are then mobilized inferiorly and the entire distal pancreas is then exposed.

Once the pancreas has been exposed (Fig. 3.3) and the short gastric vessels have been ligated, the pancreatic parenchyma and splenic vasculature are isolated and divided. These three structures (splenic artery, splenic vein, and pancreatic parenchyma) may be divided in any sequence depending on the location of the lesion, the patient’s anatomy (particularly the relationships between the splenic vessels and the gland), and whether or not splenic preservation is being considered. Pancreatic parenchymal transection may be performed anywhere in the neck, body, or tail of the pancreas depending on the location of the lesion. When transection is to be performed at the pancreatic neck the middle colic vein serves as a useful landmark to locate the SMV, which can be found at the base of the middle colic branch. The pancreatic neck is then dissected free from its retroperitoneal attachments, the superior mesenteric vein, and the proximal splenic vein. Typically the right gastroepiploic vessels and gastroduodenal artery can be preserved. For neoplastic disease, several centimeters of gland to the right of the lesion should be mobilized in order to achieve adequate tumor clearance.

The exact method for pancreatic transection and stump closure has been the subject of much debate. Sharp transection with pancreatic duct suture ligation and oversewing

of the stump has been a frequently reported technique, however more recently division of the gland with a stapling device with or without the use of SeamGuard® (Gore, Delaware, USA) staple reinforcement has been reported. All reported studies to date evaluating these techniques have been retrospective in nature except for one prospective randomized study, and no single technique has been shown to be superior. We generally divide soft glands, particularly in the area of the neck where the gland is thinnest, using the Endo GIATM Universal stapler (Covidien, Massachusetts, USA) with the SeamGuard®. In a firm or thick gland, particularly in the pancreatic body, we feel the stapler may be less effective. In these instances, we typically divide the gland sharply between 4-point hemostatic stay sutures positioned on the inferior and superior aspects of the gland (Fig. 3.4). During transection careful attention is paid to identify the pancreatic duct which is then ligated with a single figure-of-eight stitch (Fig. 3.5). The remaining stump is then oversewn with interrupted U-stitches.

of the stump has been a frequently reported technique, however more recently division of the gland with a stapling device with or without the use of SeamGuard® (Gore, Delaware, USA) staple reinforcement has been reported. All reported studies to date evaluating these techniques have been retrospective in nature except for one prospective randomized study, and no single technique has been shown to be superior. We generally divide soft glands, particularly in the area of the neck where the gland is thinnest, using the Endo GIATM Universal stapler (Covidien, Massachusetts, USA) with the SeamGuard®. In a firm or thick gland, particularly in the pancreatic body, we feel the stapler may be less effective. In these instances, we typically divide the gland sharply between 4-point hemostatic stay sutures positioned on the inferior and superior aspects of the gland (Fig. 3.4). During transection careful attention is paid to identify the pancreatic duct which is then ligated with a single figure-of-eight stitch (Fig. 3.5). The remaining stump is then oversewn with interrupted U-stitches.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree