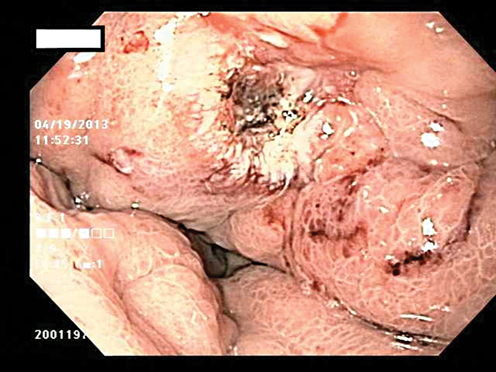

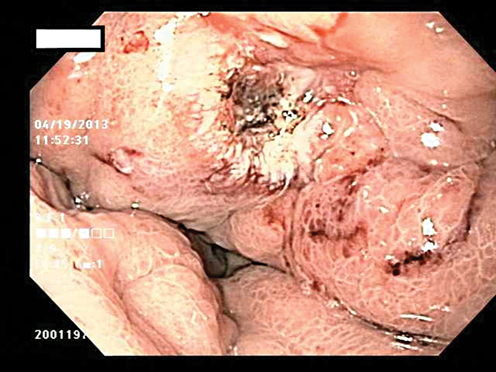

Fig. 8.1

Large ulcerated and bleeding adenocarcinoma in the antrum in a patient who presented with anemia

In early gastric cancer, abnormalities can presents as superficial plaques or depressions, polyploidy protrusions, or mucosal ulcerations. Advanced gastric cancer will usually present as a large space occupying mass, deep ulcerated lesion, or areas of abnormal infiltration and thickening. The advantage of endoscopy over other diagnostic modalities is that any abnormal area can be easily biopsied. Although it may seem obvious, the difference between benign and malignant gastric ulcers may be difficult to differentiate based on appearance alone. As a general rule, benign ulcers tend to assume regular shapes such as round or oval and have a smooth even base. The border between the ulcer and the surrounding mucosa tend to be sharply demarcated. Conversely, malignant lesions tend to have irregular shapes, possibly necrotic bases and irregular borders. Biopsy is used to establish malignancy in an ulcer and six to eight biopsies from the edge and base of the ulcer are recommended (Fig. 8.2). This will provide a 98 % sensitivity of malignancy detection. A suspicious lesion may even warrant repeat sampling at the same site in order to obtain deeper tissue, which may be harboring malignancy. This is especially important in cases of diffuse type gastric cancer (linitis plastica). These tumors tend to infiltrate the submucosa and muscularis propria and superficial biopsies may be negative. In addition, it is important to perform random biopsies beyond the lesion in question in order to increase diagnostic yield [13] (Fig. 8.3). The updated Sydney system recommends two biopsies from the corpus, two from the antrum, and one from the angularis insicura [10]. Along with biopsies, brush cytology has been used; however with adequate number of biopsy samples, this may not be needed .

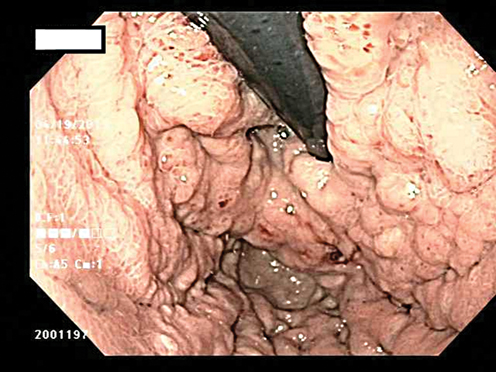

Fig. 8.2

Ulcer in the gastric cardia which was biopsy proven adenocarcinoma

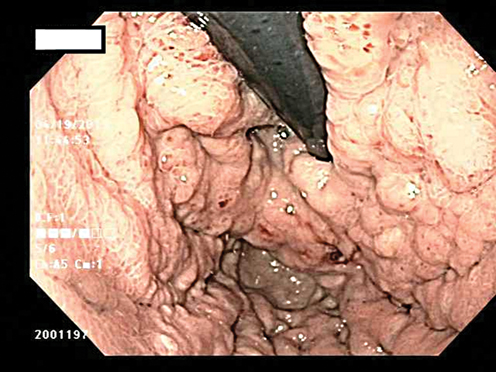

Fig. 8.3

Patient who presented with anemia and was found to have a gastric ulcer. The stomach showed poor distensibility on endoscopy and biopsies were positive for linitis plastica

Endoscopic Enhancement

Although the diagnosis of gastric cancer has been mainly achieved with standard white light endoscopy, new technologies have emerged which can now identify smaller lesions as well as provide fine endoscopic detail of the mucosa. This is especially important with the increased use of endoscopic mucosal resection. In many instances, small lesions, which may present as a flat or superficial depression, are difficult to separate from benign disease. New technologies such as magnification endoscopy, endocytoscopy, narrow band imaging, and confocal laser endomicroscopy, allow high-resolution evaluation of a suspicious area. These modalities are combined with topical stains such as acetic acid and indigo carmine which allow the endoscopist to distinguish between benign and malignant lesions. These lesions are identified by evaluating the mucosa for abnormal changes such as lack of subepithelial capillary network pattern or irregular microvasculature. Studies have also shown that with staining, carcinomas tend to return to their baseline color much faster than benign lesions [13]. In a study of 136 patients, Dinis-Ribeiro et al. were able to achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 76 % and 87 % for identifying intestinal metaplasia and 98 % and 81 % respectively for dysplasia [14]. Although these technologies have not been implemented as standard of care, they are able to identify abnormal lesions which may not have been picked up with standard white light endoscopy. As these technologies evolve, smaller lesions may be able to be picked up at an earlier stage and facilitate endoscopic mucosal resection or earlier gastrectomy with better patient outcomes.

Screening Programs

Since gastric cancer tends to present at a later stage, many countries with a high incidence of the disease have instituted screening programs. Japan uses a program where patients over the age of 40 have a double contrast barium study with a subsequent endoscopy if any abnormality is detected. In addition, serum pepsinogen tests are used to screen for patients who have risk for atrophic gastritis. Since the institution of this screening system, there has been a reduction in gastric cancer specific mortality as well as an increased 5-year survival for patients who undergo screening. Although this screening method has been validated, it is only practical and cost effective in countries with a high incidence of gastric cancer. In the USA where the gastric cancer rate is about 8x less common than Eastern Asian countries, the cost of a similar screening program is projected to be ten times more expensive with potentially no benefit. In theory, a more practical solution is to assess for the presence of risk factors and to screen those patients selectively. These would include patients with a history of previous gastrectomy, familial adenomatous polyposis, hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer or strong family history of gastric cancer. The optimal timing and subsequent interval for serial endoscopies in these high risk patients is unknown, and there is no clear evidence that screening improves survival. In most instances, follow up screening is left to the discretion of the physician based on patient history, risk factors, and findings on the initial endoscopy. Currently, mass screening does not seem practical in countries where the incidence of the disease is low [13].

Tumor Markers

Many tumor markers have been shown to have an association with gastric cancer. These include markers such as CEA, CA 19 − 9, and CA 72 − 4. However, the usefulness of these markers is up to debate with reports of varying sensitivity and specificity in the detection of disease based on tumor burden. Of the markers available, CEA and CA 19 − 9 appear to be the most useful [15, 16]. In one study performed by Nakane et al., CEA level was elevated in 249 out 865 patients with gastric cancer [3]. They were able to find a correlation with stage as well as survival. Patients who had a CEA level less than 10 ng/ml were found to have longer survival. In addition, some smaller studies have suggested a prognostic role for preoperative CA 72 − 4 levels. Despite these findings however, tumor markers have not been widely used for screening, prognosis, or for long-term follow up. The sensitivity and specificity of these markers is low and preclude any significant clinical use. A rise in tumor levels may indicate worsening disease or recurrence. Likewise, a drop in levels post treatment may indicate a response; however clinical decisions are never based upon tumor markers alone. The NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) guidelines do not include tumor markers in the workup, staging or follow-up in patients with gastric cancer .

Staging

Cancer staging is a crucial component in providing optimal treatment for patients with any malignancy. Although the components of staging may vary depending on the type of cancer, the overall goals of staging the patient remain constant. From the view of the clinician, staging identifies the most important prognostic factors for that particular tumor such as depth of invasion, tumor size, lymph node status, and the presence or absence of metastatic disease, all of which ultimately affect survival. Once the clinical staging is complete, patients are now stratified according to disease severity, and stage is able to direct the best course and order of treatment. Depending on stage, goals of treatment are defined and the patient is directed toward long-term cure, treatment to prolong quantity and quality of life but without cure, or offering palliative treatment only. Although staging is ultimately divided into four categories with several subcategories, from a practical perspective, patients are first determined to have metastatic disease or not, and are then assessed to have resectable disease or not. For patients with resectable disease, clinical staging is helpful in determining if patients are best treated with surgery first or neoadjuvant therapy, and then after surgery, when pathological staging is available, if adjuvant treatment is necessary. Certainly these decisions are best made in the multidisciplinary setting among surgeons, medical oncologist and sometimes, radiation oncologists .

Another benefit of staging is the ability to generally predict patient survival. This is important when toxic treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation need to be justified to the patient, and also to explain the patients why curative surgery is or is not an option, as most patients know that removing a solid organ cancer is the only option for cure or for long-term survival. Staging is also extremely important when entering patients into clinical trials. Most new treatments are studied within the setting of metastatic disease, so properly diagnosing stage IV disease may enable a patient to get otherwise unavailable and novel therapies. For patients in adjuvant or neoadjuvant trials, proper staging is paramount to avoid stage migration and unnecessary biases within the trial, resulting in un-interpretable data. Finally, staging provides population based statistics for different cancers, and allows outcome data for different treatment modalities to be compared on a large-scale basis. Such information may be necessary to make public health decisions, such as for screening programs or for funding for various local, state or federal programs .

The staging system for gastric cancer has undergone numerous revisions. The main tumor staging system is the AJCC/UICC TNM classification which evaluates the depth of the primary tumor, lymph node involvement, and presence of metastatic disease (Table 8.1) . Development of an effective gastric cancer staging system has been particularly difficult for many reasons. First, accumulating evidence has shown a difference in survival based on the anatomic location of tumors within the stomach. Proximal and GEJ tumors have been shown to have a worse prognosis than distal tumors. Many times these GEJ tumors are bulky and the exact origin of these tumors cannot be determined. This creates a problem of staging the malignancy as esophageal or gastric. For this reason, GEJ cancers have been further stratified by the Siewert classification, as described below. The 7 th edition of the AJCC staging also places more emphasis on lymph node involvement, which has been shown to be a major determinant in survival for gastric cancer. The number of positive lymph nodes needed to N-stage patients has changed dramatically from one edition to the next. The pendulum has swung from needing only one or two positive lymph nodes to go from one N-stage to another several editions ago, to needing many nodes for each N-category, and now back to only a few nodes in each N-stage once again in the 7th edition. These changes are all meant to more accurately stratify patient survival. Finally, there has been improved recognition that positive peritoneal cytology has a similar prognosis as distant metastatic disease and this has been appropriately reflected in the current staging system as well [8] .

Table 8.1

7th edition AJCC TNM staging system— anatomic stage of Gastric cancer

Stage 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

|---|---|---|---|

Stage IA | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IB | T2 | N0 | M0 |

T1 | N1 | M0 | |

Stage IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 |

T2 | N1 | M0 | |

T1 | N2 | M0 | |

Stage IIB | T4a | N0 | M0 |

T3 | N1 | M0 | |

T2 | N2 | M0 | |

T1 | N3 | M0 | |

Stage IIIA | T4a | N1 | M0 |

T3 | N2 | M0 | |

T2 | N3 | M0 | |

Stage IIIB | T4b | N0 or N1 | M0 |

T4a | N2 | M0 | |

T3 | N2 | M0 | |

Stage IIIC | T4b | N2 or N3 | M0 |

T4a | N3 | M0 | |

Stage IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

GEJ Tumors

One of the major changes in the 7th edition of AJCC gastric cancer staging is the management of GEJ tumors. In the past, there was ambiguity of the origin of the tumor and they could be staged as esophageal or gastric depending on the physician. After analysis of a large data set assembled by the Worldwide Esophageal Cancer Collaboration a consensus was developed to use the Esophageal cancer staging system for GEJ tumors. More specifically, any tumor arising in the GEJ or tumors that arise within 5 cm of the GEJ, and cross the GEJ are now staged as esophageal cancers. Tumors that originate in the proximal 5 cm of the stomach, but do not cross the GEJ are staged with the revised gastric cancer system. This reflects the difference in behavior of proximal versus distal gastric tumors [8].

T Staging

The revised T staging is shown in Table 8.2. The T staging is based upon the depth of invasion of the primary tumor. Important changes include the standardization of the T staging throughout the gastrointestinal system. Compared to the 6 th edition, now T1 category has been split into T1a and T1b. T1a denotes tumors that invade up to the muscularis mucosa and T1b denotes tumors that invade up the submucosa. This distinction is very important because gastric cancer, unlike other malignancies, has a propensity for lymph node metastasis even when confined to the lamina propria, so the distinction between Tis, T1a, and T1b is important and necessitates a subcategory. This is in contrast to the 6th edition in which the T2 stage was subdivided into T2a and T2b, which denoted invasion of the muscularis propria and subserosa respectively. Now tumors which invade the subserosa are classified at T3, which reflects the worse prognosis of these deeper invading tumors. Upstaging from T2 to T3 now puts each tumor in a higher grouping for all stages [17]. Another important fact to note is T3 also includes tumors that invade into the gastrocolic or gastrohepatic ligaments without perforation of the visceral peritoneum covering these surfaces.

Table 8.2

7th edition AJCC tumor staging designation—T category definitions for Gastric cancer

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

|---|---|

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial tumor without invasion of the lamina propria |

T1a | Tumor invades lamina propria or muscularis mucosae |

T1b | Tumor invades submucosa |

T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

T3 | Tumor penetrates subserosal connective tissue without invasion of visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures |

T4a | Tumor invades serosa |

T4b | Tumor invades adjacent structures |

Management of tumors which penetrate the serosa has also undergone change. Previously these were classified as T3 but with the 7th edition they have been upstaged to T4a. This reflects the understanding that serosal involvement is a negative prognostic factor and denotes a higher stage. T4b now denotes tumors which have invasion into local structures. Under the new staging, a patient could have a T4b tumor along with positive nodes and still be classified as a stage 3, showing that en bloc surgical resection of involved organs with lymph node dissection is still a strategy for curative intent and these patients have different survival compared to truly metastatic disease. Overall the T staging of the 7th edition provides synchrony among all tumors of the GI tract and reflects a better understanding of overall survival based on depth on invasion

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree