Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an idiopathic hepatitis characterized by inflammation of the liver, presence of autoantibodies, and evidence of increased gamma globulins in the serum. It represents an enigmatic interaction between the immune system, autoantigens, and unknown triggering factors. This article provides a brief summary of the diagnosis of AIH, the natural history of AIH, an approach to the treatment and follow-up of AIH, and the role of liver transplantation in the treatment of AIH.

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is an idiopathic hepatitis characterized by inflammation of the liver, presence of autoantibodies, and evidence of increased gamma globulins in the serum. It represents an enigmatic interaction between the immune system, autoantigens, and unknown triggering factors. AIH also has certain genetic predispositions, such as association with certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers, such as DR3, D52, and DR4. The clinical manifestations of this disease were described in the 1950s and despite significant advances in our understanding of the immune system, the specific cause and pathogenesis of AIH remain unknown. Although medical science has made significant advances in the treatment of many chronic liver diseases, our treatment of AIH is essentially unchanged over the last 50 years. In the last 10 years, there have been more 1800 articles dealing with this disease state, with nearly half of them devoted to the treatment of AIH. This article provides a brief summary of the diagnosis of AIH, the natural history of AIH, an approach to the treatment and follow-up of AIH, and the role of liver transplantation in the treatment of AIH.

Epidemiology

The mean annual incidence of AIH among white, northern Europeans is 1.9 per 100,000 and its point prevalence is 16.9 per 100,000 . Recent studies have documented that the incidence and prevalence of this disease have remained essentially unchanged over the last 2 decades. In Europe, AIH accounts for 2.6% of liver transplantations. In the United States, as published in 1998, AIH accounted for 5.9% of liver transplants . Like many autoimmune diseases, AIH is a disease that affects women more frequently than men with a gender ratio of 3:1 . AIH is typically a disease of younger patients but 23% of adults who have AIH develop the disease after the age of 60 . Elderly patients are more likely to have cirrhosis at presentation (33% versus 10%). This finding suggests that older individuals may have a more aggressive disease that goes undetected until considerable liver damage is done. Elderly patients also have a higher frequency of other autoimmune conditions at the time of their presentation with AIH .

Natural History

The natural history of AIH is varied and depends on host issues that are still not clearly understood. Sentinel studies in the 1970s demonstrated that patients who have untreated severe disease are likely to die within 6 months of diagnosis . These patients clearly need to be treated. Similar studies done in the latter part of the 1970s also demonstrated that certain patients who have AIH are likely to have the disease progress into cirrhosis with the typical development of esophageal varices, portal hypertension, and liver cancer . These early studies suggested that patients who have a severe acute onset of AIH should be treated. Other studies, however, have suggested that there are patients who may not need immunosuppressant therapy. The risk-to-benefit ratio of immunosuppressive therapy with its potential toxicities is not always clear and treatment must be individualized. One subgroup of patients who might not need treatment is those patients who present with asymptomatic AIH. There are few evidence-based data available to guide treatment decisions in these patients whose AIH was diagnosed solely because they have elevated transaminases. Czaja recommends that asymptomatic patients who have minimal enzyme elevations can be safely observed without the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Feld and colleagues suggest that the rationale for using immunosuppressive therapy in a patient who has symptomatic disease would be to prevent the development of fibrosis. Feld found that the degree of liver enzyme elevation or the elevation of IgG in asymptomatic patients did not predict outcome, however.

Others suggest that the liver biopsy can be used to decide if treatment is needed in asymptomatic patients. Czaja suggested that patients who had confluent necrosis on the initial liver biopsy should be treated. Others have suggested that many asymptomatic patients had only nonspecific changes on liver biopsy and that the liver biopsy was not helpful in deciding whether the patient should be treated.

A significant proportion of patients who have AIH may have cirrhosis at the time of presentation. Approximately one third of patients have cirrhosis regardless of the age at which they present . Most studies have found that patients who present with cirrhosis are more likely to die or develop complications of their liver disease during follow-up . This conclusion, however, is not universal. Roberts and colleagues found that the 10-year survival of patients who had cirrhosis was similar to that of patients who did not have cirrhosis at baseline. Patients who have cirrhosis are more likely to need to be treated for a longer time before achieving remission. These patients therefore may have a relatively poor outcome during follow-up . Overall survival rates at 5 years (79% cirrhosis versus 97% no cirrhosis) and 10 years (67% cirrhosis versus 94% no cirrhosis) are good irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis . Many centers treat patients who have cirrhosis with immunosuppressive therapy in an attempt to improve their outcomes, although there are few data to suggest that long-term treatment is beneficial . Some experts believe that patients who have “burned-out” AIH do not need to have immunosuppressant treatment. The rationale for this decision is that treatment of this inactive cirrhosis is fraught with potential side effects from the immunosuppression with little benefit.

One additional caveat needs to be addressed regarding the treatment of AIH in patients who have documented cirrhosis. Several of the largest studies were done before viral infections could be excluded in patients who had AIH. These patients who had cirrhosis who were treated with steroids may have had a flare of their undiagnosed viral hepatitis (primarily hepatitis C) contributing to their poor outcome. In addition, many patients who had non alcoholic fatty liver disease may have positive autoantibodies and little or no fat on their biopsies despite the presence of NAFLD-induced cirrhosis. Treatment of these patients with steroids, although not deleterious, would not be expected to be beneficial.

There is a growing body of literature that suggests that fibrosis and even cirrhosis attributable to AIH may be reversible with treatment of the AIH . Conversely, there are multiple reports suggesting that fibrosis may progress despite immunotherapy . It is not yet clear what differentiates these two groups of patients who respond differently to immunosuppressive therapy.

Natural History

The natural history of AIH is varied and depends on host issues that are still not clearly understood. Sentinel studies in the 1970s demonstrated that patients who have untreated severe disease are likely to die within 6 months of diagnosis . These patients clearly need to be treated. Similar studies done in the latter part of the 1970s also demonstrated that certain patients who have AIH are likely to have the disease progress into cirrhosis with the typical development of esophageal varices, portal hypertension, and liver cancer . These early studies suggested that patients who have a severe acute onset of AIH should be treated. Other studies, however, have suggested that there are patients who may not need immunosuppressant therapy. The risk-to-benefit ratio of immunosuppressive therapy with its potential toxicities is not always clear and treatment must be individualized. One subgroup of patients who might not need treatment is those patients who present with asymptomatic AIH. There are few evidence-based data available to guide treatment decisions in these patients whose AIH was diagnosed solely because they have elevated transaminases. Czaja recommends that asymptomatic patients who have minimal enzyme elevations can be safely observed without the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Feld and colleagues suggest that the rationale for using immunosuppressive therapy in a patient who has symptomatic disease would be to prevent the development of fibrosis. Feld found that the degree of liver enzyme elevation or the elevation of IgG in asymptomatic patients did not predict outcome, however.

Others suggest that the liver biopsy can be used to decide if treatment is needed in asymptomatic patients. Czaja suggested that patients who had confluent necrosis on the initial liver biopsy should be treated. Others have suggested that many asymptomatic patients had only nonspecific changes on liver biopsy and that the liver biopsy was not helpful in deciding whether the patient should be treated.

A significant proportion of patients who have AIH may have cirrhosis at the time of presentation. Approximately one third of patients have cirrhosis regardless of the age at which they present . Most studies have found that patients who present with cirrhosis are more likely to die or develop complications of their liver disease during follow-up . This conclusion, however, is not universal. Roberts and colleagues found that the 10-year survival of patients who had cirrhosis was similar to that of patients who did not have cirrhosis at baseline. Patients who have cirrhosis are more likely to need to be treated for a longer time before achieving remission. These patients therefore may have a relatively poor outcome during follow-up . Overall survival rates at 5 years (79% cirrhosis versus 97% no cirrhosis) and 10 years (67% cirrhosis versus 94% no cirrhosis) are good irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis . Many centers treat patients who have cirrhosis with immunosuppressive therapy in an attempt to improve their outcomes, although there are few data to suggest that long-term treatment is beneficial . Some experts believe that patients who have “burned-out” AIH do not need to have immunosuppressant treatment. The rationale for this decision is that treatment of this inactive cirrhosis is fraught with potential side effects from the immunosuppression with little benefit.

One additional caveat needs to be addressed regarding the treatment of AIH in patients who have documented cirrhosis. Several of the largest studies were done before viral infections could be excluded in patients who had AIH. These patients who had cirrhosis who were treated with steroids may have had a flare of their undiagnosed viral hepatitis (primarily hepatitis C) contributing to their poor outcome. In addition, many patients who had non alcoholic fatty liver disease may have positive autoantibodies and little or no fat on their biopsies despite the presence of NAFLD-induced cirrhosis. Treatment of these patients with steroids, although not deleterious, would not be expected to be beneficial.

There is a growing body of literature that suggests that fibrosis and even cirrhosis attributable to AIH may be reversible with treatment of the AIH . Conversely, there are multiple reports suggesting that fibrosis may progress despite immunotherapy . It is not yet clear what differentiates these two groups of patients who respond differently to immunosuppressive therapy.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of AIH requires the presence of many typical features and, at the same time, the exclusion of other conditions that may cause chronic hepatitis. Like many autoimmune diseases, there currently are no pathognomonic features that clearly define AIH. Instead, an international panel has developed specific criteria to include or exclude the diagnosis of AIH. These recommendations are shown in Table 1 . Other liver disease conditions that may be confused with the diagnosis of AIH are Wilson disease, chronic viral hepatitis (especially chronic hepatitis C), and drug-induced hepatitis.

| Criteria | Diagnostic features | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Laboratory | Histologic | |

| Inclusion |

|

| Interface hepatitis with or without lobular hepatitis or bridging necrosis |

| Exclusion |

|

|

|

A separate scoring system has been established by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Study Group. It is shown in Table 2 . In using this scoring system, a patient is evaluated based on 11 biochemical, epidemiologic, and clinical markers before treatment and a pretreatment score is calculated. The pretreatment score can be modified to give a posttreatment score based on the response to treatment with corticosteroids. As designated by the committee, scores greater than 15 before corticosteroid treatment are consistent with a definite diagnosis of AIH. A posttreatment score greater than 17 constitutes a definite diagnosis. Similarly, patients who have relatively low scores (less than 10) are unlikely to have AIH.

| Category | Factor | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | +2 |

| Alk phos: AST (or ALT) ratio | >3 | −2 |

| <1.5 | +2 | |

| γ-globulin or IgG (times above upper limit of normal) | >2.0 | +3 |

| 1.5–2.0 | +2 | |

| 1.0–1.5 | +1 | |

| <1.0 | 0 | |

| ANA, SMA, or anti-LKM1 titers | >1:80 | +3 |

| 1:80 | +2 | |

| 1:40 | +1 | |

| <1:40 | 0 | |

| AMA | Positive | −4 |

| Viral markers of active infection | Positive | −3 |

| Negative | +3 | |

| Hepatotoxic drugs | Yes | −4 |

| No | +1 | |

| Alcohol | <25 g/d | +2 |

| >60 g/d | −2 | |

| Concurrent immune disease | Any nonhepatic disease of an immune nature | +2 |

| Other autoantibodies a | Anti-SLA/LP, actin, LC1, pANCA | +2 |

| Histologic features | Interface hepatitis | +3 |

| Plasma cells | +1 | |

| Rosettes | +1 | |

| None of above | −5 | |

| Biliary changes b | −3 | |

| Atypical features c | −3 | |

| HLA | DR3 or DR4 | +1 |

| Treatment response | Remission alone | +2 |

| Remission with relapse | +3 | |

| Pretreatment score | ||

| Definite diagnosis | >15 | |

| Probable diagnosis | 10–15 | |

| Posttreatment score | ||

| Definite diagnosis | >17 | |

| Probable diagnosis | 12–17 |

a Unconventional or generally unavailable antibodies associated with liver disease include perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (pANCA) and antibodies to actin, soluble liver antigen/liver pancreas (anti-SLA/LP), asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR), and liver cytosol type 1 (LC1).

b Includes destructive cholangitis, nondestructive cholangitis, or ductopenia.

c Includes steatosis, iron overload consistent with genetic hemochromatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, viral features (ground-glass hepatocytes), or inclusions (cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex).

The scoring system was originally created to aid in the selection of homogeneous groups of patients who had AIH, and was primarily to be used for clinical research purposes. Currently the scoring system is most beneficial when trying to ascertain atypical or so-called “overlap” cases. The scoring system has been validated in multiple large studies with the scoring system showing good sensitivity and specificity for excluding AIH. Because AIH has various presentations that are geographically diverse , the scoring system has been validated in the United States, South America, Europe, and Asia. Another factor affecting the usefulness of the scoring system is that the prevalence and types of autoimmune markers vary considerably between patient populations of different ethnic groups, ages, and genders (see later discussion on autoantibodies). Currently, an important use of the scoring system is to exclude AIH in patients who are already known to have hepatitis C. This situation occurs fairly commonly in the treatment of hepatitis C because of the relative frequency of a positive antinuclear antibody in patients who have hepatitis C. Despite its wide use, the scoring system is not successful in excluding the diagnosis of various cholestatic syndromes from AIH .

The liver biopsy remains essential to the diagnosis and evaluation of disease severity in patients who have AIH or in whom the diagnosis is being considered. The degree of elevation of the aminotransferases does not predict the histologic pattern of injury or the degree of fibrosis. A liver biopsy is also important for diagnosing overlap syndromes such as may occur between AIH and primary sclerosing cholangitis, AIH and primary biliary cirrhosis, or AIH and hepatitis C .

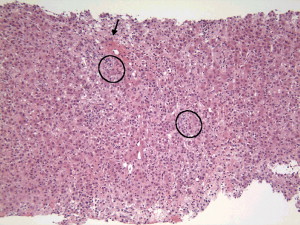

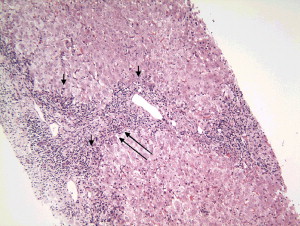

The liver biopsy typically has a portal cell infiltration that may extend from the portal tract into the lobule. A typical biopsy showing interface hepatitis in shown in Fig. 1 . The presence of plasma cells is usually believed to be the hallmark of the disease, although large studies have demonstrated that one third of patients who have well-documented AIH may have few or no plasma cells . A second classic pathologic finding in the biopsy of a patient who has AIH is a rosette of hepatocytes. A rosette is a collection of swollen hepatocytes separated from other hepatocytes that show clear signs of damage. Inflammatory cells and a collapsed stroma are also characteristic of the rosette ( Fig. 2 ) .

Traditional Autoantibodies

AIH is traditionally associated with varius autoantibodies. Three of them are found in most patients. These are an antinuclear antibody (ANA), a smooth muscle antibody (SMA), and an anti-liver/kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM). Presence of these three antibodies should be routinely determined in all patients in whom the diagnosis of AIH is suspected. Although not all patients have all three antibodies (in fact this is the exception rather than the rule), these antibodies are an important component of the definition of AIH. In addition, the presence or absence of these antibodies may serve to subclassify AIH into three subtypes .

Antinuclear Antibodies

Antinuclear antibodies are common markers of various immune-mediated diseases, including AIH. ANA may occur alone (10% to 15%) or with another antibody in patients who have AIH. Despite considerable research, the nuclear targets of ANA and AIH remain uncertain. In most laboratories the determination of an ANA is performed by indirect immunofluorescence. Literature from before 1990 put great emphasis on the pattern of immunofluorescence, describing either a homogenous or a speckled pattern. More recent studies have shown that the pattern of indirect immunofluorescence has no clinical significance, however .

For the diagnosis of AIH, it is not crucial to have a specific pattern of immunofluorescence. Knowledge of the specific molecular targets of the antibody does not increase the diagnostic precision or have prognostic importance. ANAs have been shown to react against various nuclear antigens, including the centromere, ribonucleoproteins, and ribonuclear protein complexes . In patients determined to have ribonuclear protein complexes, ANAs usually do occur in high titers exceeding 1:160. The ANA titer does not accurately predict the stage of disease, the prognosis, or the activity at the time of diagnosis .

When interpreting laboratory tests that show the presence of antinuclear antibodies, it is important to remember that ANAs can be found in various other hepatitic and cholestatic liver diseases. For instance, other liver diseases that have been associated with a positive ANA include primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, chronic viral hepatitis (especially hepatitis C), drug-related hepatitis, and even nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Evidence of a positive ANA especially in low titer does not assure that the patient has AIH. The presence of a low-titer ANA does complicate the diagnosis and potential management of patients, especially those who have documented hepatitis C .

Anti–Smooth Muscle Antibodies

Another traditional group of antibodies found in AIH are SMAs. These are a heterogeneous group of antibodies directed against various cytoskeletal proteins, including actin, tubulin, vimentin, and desmin. The presence of an SMA is common in patients who have AIH, occurring either alone or in conjunction with an ANA in up to 87% of patients. Just as a positive ANA is not specific for a diagnosis of AIH, SMAs are not specific for AIH. They occur in other chronic liver diseases and various infectious, immunologic, and rheumatologic disorders. In most clinical laboratories, SMAs are determined by immunofluorescence using either murine stomach or kidney. The pattern of immunofluorescence again is not helpful in determining prognosis nor does it increase the diagnostic accuracy. The antibody titer of SMA does not correlate with disease course or prognosis. In contrast to ANA, it has been noted in multiple studies that SMA titers can change dramatically with time in individual patients . The significance of this phenomenon is not yet known.

Anti–Liver/Kidney Microsomal Antibodies

The third traditional class of antibodies is antibodies directed against liver or kidney microsomes (anti-LKM). These are directed against specific cytochrome enzymes. In most laboratories the presence of these antibodies is detected by indirect immunofluorescence using activity against the proximal tubules of murine kidney or murine hepatocytes. Although the specific targets of ANA and SMA are largely unknown, there is a large body of literature regarding the targets of anti-LKM. For example, antibodies to LKM1 react with cytochrome monooxygenase CYP2D6. These antibodies also inhibit CYP2D2 activity in vitro . This particular antigen has been studied extensively because homologies exist between CYP2D6 and the genome of the hepatitis C virus, suggesting that AIH is the result of misdirected immunologic recognition of the hepatitis C virus. This hypothesis is in contrast to the well-recognized fact that most patients who have chronic hepatitis C in the United States do not have an anti-LKM antibody. Other members of the cytochrome P450 system, including 2C9, 2A2, and 1A2, also interact with anti-LKM.

Prevalence of antibodies to LKM depends on geography and age. Patients who have AIH in the United States rarely have an antibody to LKM (less than 4%) . Adult European patients who have AIH are much more likely to have an anti-LKM antibody with an occurrence of up to 20% in some reports. In addition, in Europe anti-LKM is commonly found in pediatric patients. It is not clear why there are such dramatic geographic differences in the occurrence of anti-LKM. It has been suggested that genetic differences in the immune response to a particular target antigen may be responsible. Despite its relatively rare occurrence in the adult United States population, current guidelines suggest that adult patients suspected of having AIH should be tested for anti-LKM .

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree