LIFE PLANNING

A patient facing ESKD must understand that no matter how successful his or her therapy (dialysis and/or transplantation), life span is less than if ESKD were not present. Therefore, it is imperative for the patient, in conjunction with his or her advisors (medical and nonmedical), to establish some form of life plan with ESKD. Early in the course of the disease, education will be important: that education coming from the patient’s research on the subject and that provided by the health care team. The strategy in developing a life plan is to live well and extend life with ESKD. To do so, one must recognize a possible distinction between quantity and quality of life. Of course, one prefers both, and an organized plan is the best way to achieve that goal. A life plan is a roadmap to such success and does so by anticipating risks and considering options. Thus, decisions become structured along the lines of the life plan. For example, a living donor for transplantation may not be available for a year, but ESKD is now. Rather than create an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), a permanent use of the vessels, consider short-term peritoneal dialysis (PD). In 15 years when the transplant is no longer functional, those vessels may be used for fistula creation, and hemodialysis (HD) can be performed with the access that offers the best chance of healthy HD. The life plan leverages all modalities over the lifetime and would emphasize the right therapy at the right time for this individual. During the education process leading to the life plan, all therapies should be presented in a positive light. Patients highly motivated and intensely engaged in their care may disparage in-center dialysis. That is not a healthy approach. All therapies must be respected as they may unexpectedly be necessary. So while discussions take place, the nephrologist should make sure that all therapies are included in a positive light. Crucial to this understanding is the recognition that transition points will inevitably occur. These are not therapy or human failures. They are events that make us change our approach. An example is an incapacitating stroke in a self-care dialysis patient who is now dependent on a helper, usually to in-center dialysis or to the rare skilled nursing facility that performs PD. This is not a “failure” to either the patient or therapy. It represents a transition point and should be described as such in the life plan’s attempt at anticipating risk. So the Life Plan is frequently revisited, and adjustments to it become a standard operation.

OPTIONS WHEN FACING LOSS OF KIDNEY FUNCTION

OPTIONS WHEN FACING LOSS OF KIDNEY FUNCTION

As chronic kidney disease (CKD) progresses, patients may die from other causes or survive to face either death from their kidney disease or seek renal replacement therapy. It takes repeated observations over time and familiarity to at least reasonably predict outcomes in this setting. More and more observations on such outcomes are being published including updated guidelines as to how best approach the decision involved (1). This becomes particularly relevant as the population ages bringing numerous comorbidities into the CKD arena. Herein, we describe a practical and successful approach to the decision making on clinical options for patients, families, and physicians as ESKD approaches.

There are several components to the decision-making processes, but first up are the team members. The patient and family with the nephrologist are the obvious participants, but also variably important are the referring physician(s), especially the primary care physician, friends, coreligionists or spiritual leaders, other patients, and CKD education team. The latter could be a designated group, a staff nurse, a nurse practitioner, a physician assistant, a dietitian, a technician, or a home dialysis trainer. Oftentimes, this may be just the physician using visit discussions, written and/or online materials, or videos provided by kidney organizations or dialysis providers. The key here is to individualize the education to suit the patient and family’s unique situation, including economic status, education, discipline, and overall stability. This cannot succeed without the knowledge of these conditions by the attending nephrologist(s), hence the previous comment on familiarity. Repetition helps, even when initially rejected as consuming too much time.

For the education process to succeed for the unique situation for that patient, the nephrologist must offer, or have at immediate access, all services needed for an integrated ESKD care system. For what is available in 2015 that includes conservative care, in-center dialysis, home dialysis, and transplantation (FIGURE 39.1). Some of those services may be indirectly provided by referral or specifically and directly provided by the attending nephrologist.

PATIENT PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS

PATIENT PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS

Occasional patients facing ESKD are completely unaware of their disease and have no preparation for the shock facing them. In those situations, salvage approaches are required with an increasingly popular approach to urgent start PD (further discussion in the following text). However, even patients unaware of their situation can be rapidly educated to the point of at least making some informed decisions. Easiest of all is to simply insert a central venous catheter (CVC) and initiate HD. However, this often sets the stage for complacency where in-center HD with the CVC becomes permanent. We strongly urge the rejection of this approach unless a life-threatening need can only be addressed by the CVC. So in this situation, the patient’s personal characteristics have an immediate and dramatic influence on decisions.

Far more often however is the case where the patient has been seeing a physician and often a nephrologist for months. It is in this setting that some of the most rewarding aspects of delivering chronic care are experienced. Learning about the patient, the family, life style choices, health status, needs, wants, and desires all contribute to advising patients about their options. Education status may play a role but is often for secondary to psychosocial and economic issues. Fear is not unique to any groups. Explanations and instilling confidence can often overcome fear. Throughout this process of probing, provoking, listening, and addressing, patients, families, and the physician all acquire knowledge such that more informed advice is given and decisions made.

It is through this process that a sequence of decisions is made. Without the knowledge of the physician about the patient and the patient about the options, unsatisfactory decisions are likely to result. The first decision is whether to actively pursue some form of renal replacement therapy versus letting nature take its course with progressive kidney failure and ultimate death from it. Not embarking on replacement therapy is called undergoing conservative care. It is imperative that the physicians involved in the care and decision making emphasize that there is no abandonment of care. Depending on the patient’s and family’s preferences, the primary care provider under conservative care could well be the nephrologist. This is just one of the many shared decisions. In any case, all of the care providers must be prepared to acknowledge that abandonment is not going to occur at any level.

Too often, this first decision is never formally addressed, and assumptions are made about renal replacement therapy. We consider this a serious mistake both ethically and practically. Without a complex ethical argument, informing/discussing conservative care is mandatory simply because it is an option, and no options are withheld in this setting. Practically, it is important because it empowers patients about a choice, and if they are making a choice to pursue renal replacement therapy (versus death from kidney failure), then they are committing to the attempt to succeed at the renal replacement therapy.

The second decision is a derivative of the first. Having decided to pursue renal replacement therapy will then lead to deciding on preemptive transplantation versus dialysis. Often, this decision is out of the hands directly of the patient and physician due to availability of a donor kidney. Nonetheless, the decision step is important for the same reason, as in the first decision. It requires an education, understanding, and commitment, all critical attributer for success. Because of health conditions, transplantation may be eliminated, but the understanding of why that is so is helpful and educational going forward with dialysis and the subsequent decisions.

If transplantation is not an immediate option, then the third decision is what type of dialysis will be performed. This third decision is then dialysis at home versus dialysis at a center. While independence often dominates this decision, other important factors contribute. Here again, knowledge about the patient is beneficial. Patients have fears about self-care, may have other dominating obligations at home, or may prefer to be around other patients with similar conditions. That can work the other way as well because the sicker ESKD patients are often dialyzed in-center. Nonetheless, the third decision of dialyzing at home or in-center is an important shared decision requiring thoughtful knowledge and understanding.

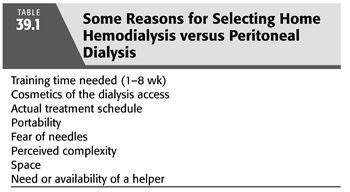

Because there are only limited in-center PD programs, for these purposes, we will consider in-center dialysis to mean HD. Thus, if the third decision is in-center dialysis, by virtue of the aforementioned assumption, that implies HD. However, if the third decision is to perform home dialysis, then the fourth decision is HD versus PD. Some of the reasons for selecting either of these options are listed in TABLE 39.1. Our dialysis program varies at any time between one-quarter to one-third of all patients dialyze at home, so our experience with this decision process is vast. While it would be ideal if all aspects of the two therapies would be considered in this decision, that is typically not what occurs, despite our best efforts to make it so. The overriding factor tends to be the time necessary for training. By virtue of its simplicity and less severe immediate complications, PD takes 1/2 to 1/8 of the training time than does home HD. Furthermore, HD generally requires another person so that training time commitments involve two people. Thus, at least in our program and we suspect in many others, patients choosing to dialyze at home tend to make PD the fourth decision. We do not prefer PD over home HD except in special circumstances such as very poor options for angio access, and in marginally stable patients who do not have a helper for home HD. The fourth decision can be made in a short time frame when circumstances dictate. PD can still be a viable option in this urgent setting. Small-volume supine exchanges can be performed either in the home training unit or hospital while the catheter implant heals.

The fifth and final decision in our options process is what type of home HD or PD is preferred. Our HD options include nocturnal three to six times per week, daytime thrice weekly, traditional flows and times, and short frequent HD which averages 5.2 times weekly, generally for about 2.5 hours. It is with these varieties of HD that the greater difference in training time is noted. In New Zealand, some HD training may last for many months, whereas in our program, 2 to 3 months. Rarely is this training on specific technique but more likely to concern preparation for complications. For nocturnal, especially when performed more than thrice weekly, and for short frequent HD, because of the frequency, complications are less frequent and often never observed during training. Hence, the duration of training tends to be far less than training for traditional thrice-weekly HD. The decision on frequency of HD depends on many factors such as status of access, hemodynamic stability, psychosocial factors, availability of a helper, time to set up and take down the equipment, and many more. We try to determine this at the time of the fourth decision, so factors of the fifth decision impact on the fourth decision. For PD, a helper is less often needed and manual exchange techniques are generally learned within 2 weeks. Cycler techniques can be learned in this same time frame, and in the United States, 80% of PD patients utilizes a cycler in what is termed automated PD. As in the varieties of home HD, the varieties of PD are often determined as part of the fourth decision, home HD versus PD.

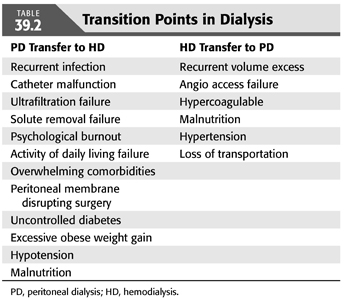

The last point to be made regarding dialysis options is the flexibility to accept that in a dialysis patient’s lifetime, there will be transitions from one therapy to another. These are almost inevitable and should be truly considered transitions of therapy rather than a failure of a patient or the therapy. We refer to these transitions points as moving in either direction and as guides to selecting and utilizing the right therapy for that patient at that point in time (TABLE 39.2).

ROLE OF EDUCATION AND CONSERVATIVE CARE

ROLE OF EDUCATION AND CONSERVATIVE CARE

Section: Role of Education

The commencement of maintenance dialysis is a major life-altering event (2), and a patient-centered approach which involves a partnership among nephrologist and other health care providers, patients, and their families should be established to ensure that decisions respect patients’ wants, needs, and preferences and that patients have the education and support they need to make decisions and participate in their own care. Clinical guidelines recommend that treatment option for CKD include the preference of a fully informed patient (3).

However, data from observational studies and the United States Renal Data System suggest that patients with CKD may not be presented with adequate information on treatment option or given sufficient time in which to discuss management alternatives with their family or caregivers (3). Incomplete presentation of treatment option and poor education are responsible for the inconsistencies noted in most studies about the preferred and actual modality of patients’ treatment choice (2).

Patient and Family Education

Most CKD patients at baseline generally do not have sophisticated knowledge about their kidney disease or modalities of management of ESKD. This also causes a significant amount of worry. Finkelstein et al. (4) in their study about perceived knowledge among patients about CKD and ESKD therapies noted that 23% patients reported having extensive knowledge, while 35% reported no knowledge about their disease. Also, 43% reported having no knowledge of HD, 57% had no knowledge of chronic ambulatory PD, 66% had no knowledge of automated PD, and 56% had no knowledge of transplant. A total of 35% of patients had no knowledge of therapeutic modality for ESKD.

From the 2012 United States Renal Data System, 114,813 incident ESKD patients began renal replacement therapy with 98,954 starting HD, 9,175 PD, and 2,803 receiving a preemptive kidney transplant—this data has remained relatively stable over the past years. The United States Renal Data System (Wave 2) Study surveyed patients shortly after they initiated renal replacement therapy, with either of HD or PD, to determine who took the lead in deciding on the mode of dialysis. Among the patients who received HD, 53% had physicians taking the lead, 17% patients, and 30% had a joint decision. Of the patients undergoing PD, physicians led in 17%, patients in 36%, and joint decision in 48%. Thus, of all the patients undergoing PD, 84% had contributed substantially to the decision, whereas of all patients undergoing HD, only 47% contributed to the decision.

Mehrotra et al. (2) examined the effect of pre-ESKD processes on the selection of renal replacement therapy among incident ESKD patients (2). Of the 1,365 eligible patients, 93% was undergoing maintenance HD and 7% were undergoing PD, and of the 427 who completed the study, 94 % were on maintenance HD and 6% on PD. In this study, they found that 70% of incident HD patients reported that chronic PD was not offered as an option for renal placement therapy. However, they noted that there was a strong relationship between the probabilities of presentation of PD as a treatment option to the selection of PD as a treatment modality.

Patient education has multiple benefits. It allows an informed choice of renal replacement therapy, improves patient–doctor relationship, and also enhances compliance (5). Studies have suggested that education of CKD patients can delay the onset of dialysis and improve outcomes after they start dialysis (4). Also, provision of educational programs for patients with CKD can increase the percentage of patients who will start dialysis with less expensive self-care as opposed to traditional facility-based, standard care dialysis, and significantly reduce urgent dialysis which might impact on patient survival given that the mortality rate in emergent situation is high.

With a CKD, patient education is not just nice to have—it is fundamental to long-term survival. The content and depth of patient education should be guided by current best practices. To achieve improved outcomes, we must emphasize predialysis and dialysis education and ensure that it is designed to empower patients (6).

Nephrologist Education

Providing education about therapy options to patients with CKD/ESKD is uniformly accepted as important; however, there appears to be a problem in its delivery (7). There is a significant relationship between the timing of presentation to the length of time the patient knew of his or her kidney failure and the duration of predialysis nephrologist care (2). Research on nephrologist–patient communication suggests that nephrologist provides information on treatment option over an extended period of time but increases the amount of detail about specific treatment when the patient requires renal replacement therapy (3). This approach reduces the amount of time available to patient to make decision and means that information provision may coincide with the time patients are symptomatic and cognitively impaired to make informed decision about their treatment. The value of education and an appreciation for the timing for its occurrence are clear (7); thus, nephrologists should be educated to be aware of this challenge that limit effective communication with patients and work in a timely manner so that patients’ knowledge of ESKD is improved.

In terms of modality selection when patients approach ESKD, nephrologists have reported that patient choice is the most important factor in choosing a dialysis therapy, yet there exists a disparity in knowledge of the different treatment options (4). For example, there has been a renewed interest in home HD, but as Jayanti et al. (8) showed, despite the interest and belief in this therapy among providers, home HD is still not available to a majority of patients. Suboptimal patient preparation pathways, lack of appropriately trained personnel, and physician unwillingness were some of the key barriers to widespread adoption of this therapy resulting in the disconnect between belief and practice of home HD. Adequate exposure of physicians during their fellowship to the various modalities of dialysis will give them the capacity to educate patient on treatment options and also care for them, and as Jayanti et al. (8) noted, a generation of nephrologists may lose out to the training opportunities in this field if knowledge of home-based dialysis is not made an integral part of the training curriculum.

Other Provider Education

Given the complexity of CKD, patients approaching ESKD are often managed by a multidisciplinary team—primary care provider, nurses, dietitians, social workers, and other medical specialist (cardiologist, endocrinologists, etc.). Encounter with these providers has a potential effect on a patient’s knowledge, belief, and attitude about CKD, ESKD, and treatment modalities.

The recognition of early CKD and referral to a nephrologist is an obligation providers have to these patients. Timing of referral of patients with CKD to a nephrology service affects their outcomes. The majority of patients with kidney disease are referred close to the time of initiation of renal replacement therapy, which contributes to poor patient outcomes on renal replacement therapy (e.g., the use of central venous catheters vs. AVFs). There are now several measures that have proven efficacy for slowing progression of CKD and a number of treatments that are effective at preventing and reversing the morbidity of CKD that patients will benefit from if they are referred early to nephrologists. Also, timely referral can allow informed decision to be made about renal replacement therapy.

Other providers who are directly involved in provision of ESKD treatment modalities should have a purposeful education about renal replacement therapies as inexperienced staff might present negative views about treatment modalities. A synchronized education of these providers leads to a consistent message transmitted to patients about the various treatment modalities (7).

Role of Conservative Care

Definition

Conservative care or nondialytic treatment is a viable option in the integrated management of patients with advanced CKD. It includes treatment of anemia, bone mineral metabolism disorders, hyperkalemia, metabolic acid–base abnormalities, hypertension, and protein-energy malnutrition associated with CKD. Conservative care also pays careful attention to psychological, social, and spiritual support to the patient as well as their families. Furthermore, it involves advanced care planning and adopting palliative care principles to improve symptom burden and functional status to maximize quality of life (QOL) prior to death.

It is crucial to learn about the statistics of CKD in the elderly.

Incidence and Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Kidney Disease in the Elderly

Important subsets of CKD population are the elderly. They are the fastest growing CKD subset. The percentage prevalence of all CKD in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) population with age 60 years and older is 33.2%, compared to 8.9% in the 40- to 59-year-old subset during 2007 to 2012. Of these, the percentage prevalence of CKD with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is 22.7% in the age group >60 years of age compared to 2.3% in 40- to 59-year-old subset (9).

The elderly is also highly represented in the prevalent and incident cases of ESKD. The prevalence of ESKD increases in all age groups, with a sharp increase in ages 45 years and older (FIGURE 39.2) (9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree