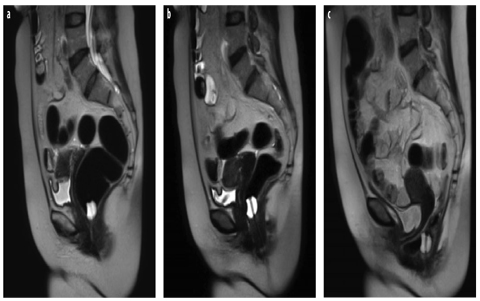

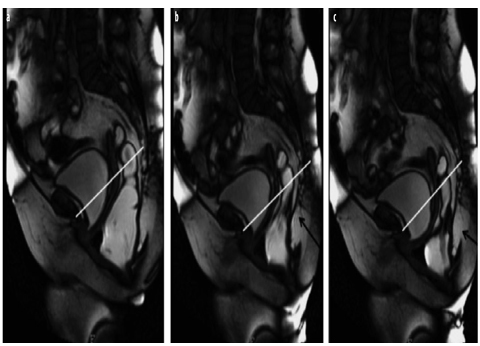

Fig. 1 a–c

Anorectal angle variations. a Sagittal T2-weighted image at rest after rectal filling with gel. The pubococcygeal line (PCL) (black line). At rest, the anorectal angle (ARA) (white line) is approximately 85°. The anorectal junction (ARJ) corresponds to the apex of the angle and it is placed at the level of the PCL. b Sagittal T2-weighted image during contraction of the pelvic floor: the ARA (white line) is reduced to <80°. c In this patient with obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), during straining, the ARA opens >130° due to rectal prolapse (>160°) and is associated with severe ARJ prolapse (>6 cm)

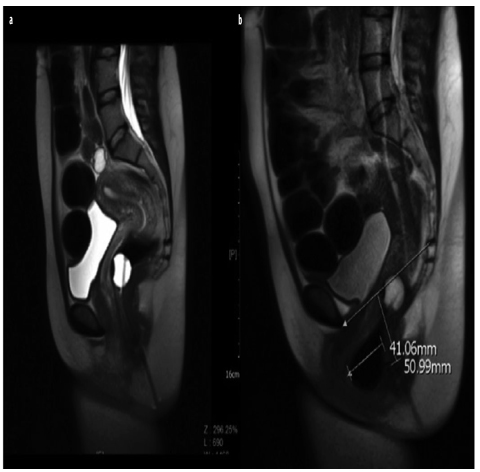

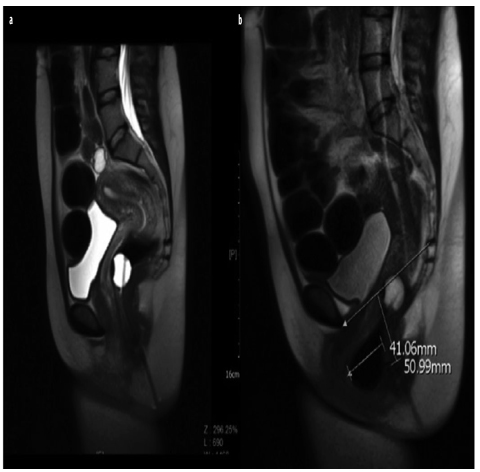

Fig. 2 a–c

Anorectal angle (ARA) variations. a Sagittal T2-weighted image at rest after rectal distension with air through a balloon Foley catheter. At rest, the ARA is approximately 90°. The anorectal junction (ARJ) corresponds to the balloon filled with fluid. b Sagittal T2- weighted image during contraction of the pelvic floor: the ARA reduces to <90°. c In this patient with obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), during straining, the ARA opens >130° due to the rectal prolapse (>160°) and is associated with severe ARJ prolapse (>6 cm), cystocele, and colpocele. An anterior rectocele with rectal invagination is also visible

Pubococcygeal Line

Using the PCL-POP staging system at the level of any pelvic compartment, a prolapse is considered small if the reference point is 1–3 cm below the PCL, moderate if between 3 and 6 cm below the PCL, and large if >6 cm below the PCL. The “rule of three” is useful in grading POP using the PCL system: prolapse of an organ below the PCL by ⩽3 cm is mild, by 3–6 cm is moderate, and by >6 cm is severe [5, 25–27].

Midpubic Line

Using the MPL-POP staging system, any POP is classified as stage 0 when the reference point is 3 cm above the MPL, stage 1 if >1 cm above the MPL, stage 2 if ⩽1 cm below the MPL, stage 3 if >1 cm below the MPL, and stage 4 represents complete organ eversion.

H Line, M Line, Organ Prolapse System

Another grading system is the H line, M line, organ prolapse (HMO) system, which is based on H and M lines [26]. The H line extends from the inferior aspect of the pubic bone to the posterior wall of the rectum, representing pelvis hiatus widening; the M line, which extends perpendicularly from the PCL to the H line, represents hiatal descent. The HMO system is applied to a midsagittal image obtained during maximal patient straining.

Using the PCL as the main anatomical landmark is certainly easier for the radiologists. In a healthy patient at rest, the base of the bladder, the upper third of the vagina, and the peritoneal cavity should project superior to the PCL (Figs. 1 and 2). The distance from the PCL to the bladder base, uterine cervix, and ARJ, measured on images obtained when the patient is at rest and at maximal pelvic strain or evacuation, indicates prolapse severity. The same reference parameters used in conventional defecography may be adopted for DPF-MRI. The ARA is the angle formed by a line along the posterior border of the rectum and a line along the central axis of the anal canal. Its changes express the functioning of the puborectalis muscle: when the pelvic floor and puborectalis contract, the angle closes (squeezing), whereas during straining and evacuation, it opens.

In our experience, and according to other authors, in healthy individuals in the supine position, the ARA at rest is between 85 and 95° [7]. During squeezing (maximal pelvic floor contraction), pelvic organs elevate in relationship to the PCL, sharpening the ARA by 10–15° (due to contraction of the puborectal muscle). During straining and defecation, the ARA becomes more obtuse, typically by 15–25°, than when measured at rest.

Posterior Pelvic Floor Dysfunctions

Rectocele

Rectocele is defined as an outpouching or bulging of the anterior rectal wall that develops during defecation. It is observed in most parous women (78–99%) but is rarely seen in men. The underlying etiology of a rectocele is weakening of the support structures of the pelvic floor, particularly of the rectovaginal fascia [29]. Several factors may increase the risk of developing a rectocele, such as vaginal birth trauma (multiple, difficult, or prolonged deliveries; forceps delivery; perineal tears), constipation with chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure, hysterectomy, aging, and congenital or inherited weaknesses of the pelvic floor support system [29].

Most rectoceles develop anteriorly due to weakness of the structures sustaining the anterior rectal wall. A rectocele rarely develops posterolaterally; in this case, the lesion — a posterior perineal hernia — occurs laterally through a puborectalis muscle defect rather than in the midline [6–8, 29]. Rectal invagination is frequently associated with rectoceles [6–8, 21, 29]. Anterior rectoceles are specifically associated with rectal wall invagination and infolding of the posterior rectal wall. Rectoceles are also frequently associated with enteroceles and anismus; enteroceles or peritoneoceles may act as compensatory dysfunctions, improving evacuation from the rectocele and reducing fecal trapping.

Symptoms related to rectocele may be primarily vaginal (bulging, dyspareunia) or rectal (defecatory dysfunction, constipation, and sensation of incomplete evacuation). Fecal trapping in the rectocele leads many patients to empty it by digitating and pressing on the posterior wall of the vagina or perineum.

Sensitivity of the clinical examination in rectocele diagnosis varies from 31% to 80% [3, 4, 29] and is generally unable to distinguish an enterocele from a high rectocele. For these reasons, dynamic MRI during maximal straining and/or evacuation is clinically useful to identify and grade rectoceles (Fig. 3). Clinically relevant symptomatic rectoceles >3 cm are easily detected at supine MR defecography and DPF-MRI (Figs. 1–4). Rectoceles <2 cm are considered normal features in most parous women rather than clinically relevant features [6–8, 29]. At MRI, a rectocele is measured during the phase of maximal straining and evacuation as the distance between anal midline and the anterior rectal wall or as the depth of wall protrusion beyond the expected anterior rectal wall. At MRI, rectoceles are graded as small if <2cm, mild as being between 2 and 4 cm, and large if >4 cm [7, 19]. By using this staging system, MRI sensitivity in detecting large rectoceles (>3.5 cm) ranges between 87% and 100% [19, 20].

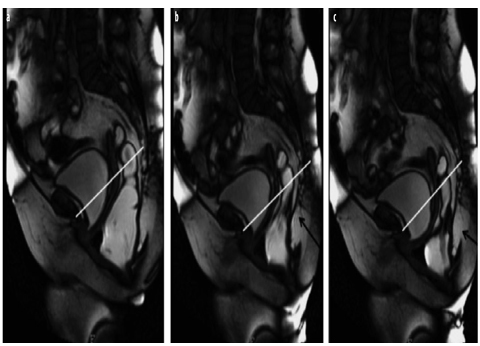

Fig. 3 a,b

Rectocele. a Sagittal T2-weighted image at rest after rectal filling with air through a balloon catheter. b During straining, a large anterior rectocele develops (>4 cm) and is associated with prolapsed anorectal junction (ARJ) (>5 cm)

Fig. 4 a–c

Rectocele with rectal invagination during progressive straining. a Sagittal balanced image after filling with rectal gel shows an anterior rectocele (>3 cm) associated with prolapsed anorectal junction (ARJ) (>5 cm). b Progressive straining shows rectal invagination above the rectocele. c Rectal invagination and rectocele are more evident at maximum straining during evacuation

Rectal Intussusception

Rectal intussusception is invagination of the rectal wall [6–8, 29] located either anteriorly, posteriorly, or circumferentially, and may involve the full thickness of the rectal wall or the mucosa only. Rectal intussusception is classified as intrarectal if it remains within the rectum, intra-anal if it extends inside the anal canal, or extra-anal if it passes the anal sphincter; the latter is also called complete or full rectal prolapse [18, 19]. Rectal intussusception is unlikely to obstruct defecation, but it can cause a sensation of incomplete emptying. If the invagination progresses becoming intra-anal, patients most likely experience a sensation of incomplete defecation due to outlet obstruction. Invagination may also cause sequestration of a rectocele, with contents returning into the rectum during relaxation, thus resulting in incomplete evacuation and OD as well (Figs. 2 and 4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree