Fig. 9.1

Todani classification of congenital bile duct dilatations (Reprinted from Todani [6] with permission of Springer International Publishing)

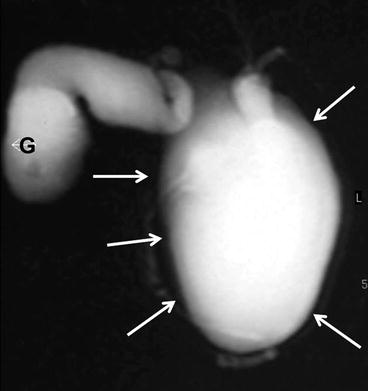

Fig. 9.2

MR cholangiography: type IA choledochal cyst (arrows). G gallbladder

Fig. 9.3

MR cholangiography: type IB choledochal cyst. Segmental cystic dilatation of CBD (yellow arrow), with normal proximal and distal CBD (white arrows); gallbladder (head arrow)

Fig. 9.4

Type IC choledochal cyst; (a) MR cholangiography with evidence of distal obstruction (white arrow). (b) Endoscopic cholangiography: lithiasis of distal CBD (white arrow)

Fig. 9.5

Thirty-six-year-old patient; MR type IVA congenital bile duct dilatation. Choronal view (a), MR cholangiography (b): bilateral intrahepatic cystic dilatations with lithiasis (white arrows) and stones in choledochal cyst (yellow arrow)

Fig. 9.6

Endoscopic cholangiography: type IVB choledochal cyst. Multiple and segmental dilatations of the extrahepatic biliary tree (white arrows). Main pancreatic duct (yellow arrow)

Fig. 9.7

MR cholangiography: type V congenital bile duct dilatation (Caroli’s disease)

Fig. 9.8

Endoscopic cholangiography; type V congenital bile duct dilatation (type 3 according to Guntz classification): saccular dilatation of left hepatic duct with intrahepatic lithiasis (white arrows)

9.2 Etiology

The etiology of congenital bile duct dilatations is not fully understood. As regards Todani’s types I–IV BDD, several theories have been proposed, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is the long common channel theory of Babbitt [4, 7, 11]. An anomalous biliopancreatic junction (ABPJ ) (Fig. 9.9) with a common channel longer than 10–15 mm may allow pancreatic juice to reflux into the biliary tree, with activation of pancreatic enzymes. These active enzymes cause inflammation and deterioration of the biliary duct wall, leading to dilatation [12]. This hypothesis is supported by the detection of high concentrations of amylase in the bile of these patients [7, 13]. Furthermore, greater pressures in the pancreatic duct can further dilate weak-walled cysts [5, 14]. The incidence of ABPJ ranges from 96 to 100 % in pediatric series and from 68 to 94 % in adult series [4, 7, 11]. However, it should be considered that long common channels are arbitrarily defined in terms of length, with wide variation in measured length, from 10 to 45 mm, based on imaging modality and angles [5, 15].

Fig. 9.9

MR cholangiography and sketch: type IA choledochal cyst, with evidence of ABPJ with long common channel

Congenital nature of choledochal cysts has also been reported as a possible etiology of BDD [16]. This theory states that embryologic overproliferation of epithelial cells results in dilatation during the cannulation period of development [5]. Davenport and Basu [17] reported that all neonatal choledochal cysts were cystic in nature and pathologically had fewer neurons and ganglions than those in normal bile ducts. Their theory was that round cysts are congenital in nature, with distal obstruction due to aganglionosis, dysmotility, and functional CBD obstruction (equivalent to achalasia of the esophagus or to Hirschsprung’s disease of the colon) [5]. Other authors speculate that all adult cysts are acquired due to distal obstruction, with longer, narrower stenosis leading to round lesions and shorter wider stenosis leading to fusiform lesions [17, 18]. The distal obstruction may be due to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or scarring and stone formation into an ABPJ [19, 20]. The same authors argue that Todani’s type IVA cysts result from combined distal as well as hilar and intrahepatic stenosis [5, 18].

Intrahepatic BDC, corresponding to type V in the Todani classification, results from embryological malformation [11]. Embryology of the intrahepatic biliary tree is as follows: a single layer of cells called ductal plate forms around the portal branches, which then duplicate to form a double layer [5]. Remodeling and selective reabsorption of the ductal plate start in the 12th week and progress to form the large bile ducts at the hilum and proceed toward the small ductules in the periphery. When such ductal plate malformation occurs at the level of the large ducts, Caroli’s disease results; malformation that continues during later stages involving the development of the peripheral ductules results in Caroli’s syndrome , that is, association of intrahepatic biliary cysts, reflecting large duct arrest, and congenital hepatic fibrosis, reflecting ductile arrest [21, 22]. Caroli’s disease can be associated with biliary atresia, which is also thought to be due to ductal plate malformation. Caroli’s disease can also be associated with both autosomal recessive and, less commonly, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease [23–25].

9.3 Clinical Presentation

BDD may remain asymptomatic for many years and diagnosis may be obtained on imaging studies for unrelated causes [7], but 80 % of patients present symptoms before the age of 10 years [26]. The classic triad of abdominal pain, jaundice, and a palpable abdominal mass occurs in less than 20 % of patients, although almost two-thirds of patients have two of these three symptoms [26].

Neonatal patients generally present with obstructive jaundice (58 %), biliary pain (52.3 %), abdominal masses (17 %), and fever (12.5 %) [1]. The classic triad occurs in 3 % of cases [1]. Complications, as cholecystitis or cholangitis occur in 3–6 % of patients and acute pancreatitis was reported in 21 % of cases [1].

In adult patients the most common symptom is biliary pain. In a recent analysis of literature on 1,639 patients, biliary pain occurs in 71.4 % of cases, jaundice in 26.1 %, and a palpable abdominal mass in 2.5 %; the classic triad occurs in only 1 % of cases [1]. Complications are more commonly observed in adult patients, especially in those with a long history of previous biliary surgical and nonsurgical treatments. According to an analysis of 1,581 patients in literature, pyogenic cholangitis is the most common clinical occurrence, occurring in 23 % of cases (15–41 %), and acute pancreatitis is described in 13.6 % (10–55 %), and it is strictly related to the presence of an ABPJ (p < 0.006) and to the size of BDD (p < 0.004) [27]. Acute cholecystitis occurs in 18 % of cases. Associated biliary lithiasis is associated in 38–87 % of patients [1].

In the multicenter study on BDD conducted under the auspices of the French Association of Surgery [1], neonatal patients present more frequently more than one symptom (p < 0.0001), palpable abdominal mass (p < 0.0001), jaundice (p = 0.0001), and acute pancreatitis (p = 0.03). On the contrary complications (p = 0.0466) and especially cholangitis (p = 0.0023) are significantly more common in adult patients.

The mean time elapsed from the appearance of symptoms to diagnosis and treatment is significantly longer in adults than in children and for adult patients was estimated to be up to 6 years [7]. Previous hepato-biliopancreatic treatments including cholecystectomy or other surgical/endoscopic/percutaneous biliary procedures before diagnosis are commonly reported in the adult population (10–50 %) [7]. Moreover, patients might also be referred for recurrent pancreatitis related to incomplete resection of the distal part of the extrahepatic dilatation. Previous biliary surgery is associated with more complex management of the disease in adult patients [7].

9.4 Evolution

Stone formation secondary to bile stasis is the most frequent condition occurring in adults, affecting 37.5–74 % of BDD patients [7]. Half of the cases of Todani’s type V BDD are associated with coexistent congenital hepatic fibrosis that corresponds to an inherited congenital malformation transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait [7, 28]. The most important late consequences are cirrhosis and portal hypertension. A significant association between BDD and cholangiocarcinoma (CC) is unanimously reported with a clear increasing age-related incidence. In previous series, the risk of developing a CC is estimated from 20 to 30 times higher than in normal population [4]. Recently two epidemiological studies report that presence of BDD increases 47 times the risk of developing a extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [29] and from 10.7 to 36.9 times the risk of developing a intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [29, 30]. Moreover CC over BDD occurs at a mean age of 32 years that is about two decades earlier than in the general population [4]. Malignant degeneration can occur in all types of bile duct dilatation. The majority of BDD affected by a cancer are types I and IV according to Todani’s classification [2]; a cancer can be observed in all other types of BDD, but analysis of incidence is hindered by their rarity. In an analysis of a series of 63 biliary cancers on BDD, Todani et al. [31] reported a tumor incidence of 68 % in type I, 5 % in type II, 1.6 % in type III, 21 % in type IV, and 6 % in type V. Recently a retrospective Korean multicenter study [32] reports a significantly higher-incidence bile duct cancer in BDD type IVA (13/40, 32.5 %) and of gallbladder cancer in type I (28/35: 80 %). Presence of an ABPJ has a 16–55 % risk of malignancy, with or without congenital bile duct dilation [5]. Cancer usually occurs within the cyst in saccular choledochal cyst (type I A) and in the gallbladder in fusiform choledochal cyst (type I C), leading some authors to postulate that malignancy occurs at the site of bile stasis, irritation, and inflammation (within the dilated cyst in cystic choledochal cyst and within the gallbladder when no dilatation or fusiform choledochal cyst exist) [5]. In patients with type II BDD, the incidence of synchronous cancer was 5.3 % in a recent European Multicenter Study of the French Surgical Association [33].

The incidence of malignancy with choledochocele is perceived to be low but an analysis of the literature is difficult for the confusion concerning the presence of a primary ampullary tumor. In a revision of the literature reported in the Monography of the French Surgical Association [1] on 330 patients with choledochocele, the incidence of cancer is 6.6 % (ranging from 3.5 to 27 %), including ampullary and pancreatic tumors in addition to cancers of the biliary tract.

A previous cystoduodenostomy or cystojejunostomy is a significant risk factor for the development of a tumor that typically occurs earlier than in patients not undergoing cysto-digestive anastomosis [1]. Out of the 241 cases of carcinoma collected by Todani et al. [34], 45 (18.6 %) were encountered following previous cyst-enteric drainage procedures with a mean interval between the biliary bypass procedure and the detection of carcinoma of 10 years. These features support the recommendation that low-risk patients, even asymptomatic, should undergo elective excision of BDD, even if previously treated by cystoenterostomy .

Most importantly, patients with Todani’s type V BDD are at high risk to develop intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, either synchronously or after incomplete resection. The reported average prevalence is close to 7 %, but higher values of up to 25–30 % have been reported [10]. The prevalence of cholangiocarcinoma in a recent French multicenter study [10] was 5.2 %, but the same authors stated that this prevalence may be underestimated because the series is a retrospective and multicentric study and therefore patients with malignancy who did not require surgery were not included in the study.

Histologically, biliary cancer is predominantly a mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (Fig. 9.10) and less frequently a papillary CC intraductal type (Fig. 9.11).

Fig. 9.10

Seventy-five-year-old male patient with left unilateral BDD and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. MRI axial view (a) and MR cholangiography (b): dilated left biliary tree (white arrows) and suspect intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (black arrow). (c) Surgical specimen after left hepatectomy: mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (black arrow) and dilatation with lithiasis of left biliary tree

Fig. 9.11

Abdomen MRI: dilated right bile ducts with papillary intraductal-type cholangiocarcinoma (white arrows)

9.5 Therapy

9.5.1 Surgical Treatment

Factors to consider during definition of optimal surgical treatment of BDD patients are the following: age, symptoms and complications, coexistent liver or biliopancreatic diseases, previous cyst-related surgical procedures, cyst type on imaging studies, and age-related risk for synchronous malignancy [7].

9.5.2 Type I

Complete cyst excision of the extrahepatic component of BDD combined with cholecystectomy (Figs. 9.12 and 9.13), followed by Roux-en-Y biliary reconstruction, is considered the treatment of choice for type I and type IV BDD [4, 7, 11] . A cholecystectomy is recommended due to the high risk for gallbladder malignancy , especially when ABPJ is present [7]. Treatment of BDD by cystoenterostomy is not recommended [4, 7, 11] because the drainage provided by a cysto-enteric anastomosis is associated with biliary stasis, stone formation, and recurrent cholangitis, and these lead to malignant transformation [7]. Most importantly, indeed, surgeons found that leaving the cyst intact carried a significant risk of malignant transformation [35]. The overall success rate of internal drainage procedures is 30 %, the risk of postoperative malignancy is 30 %, the mortality rate is 11 %, and more than half who undergo this procedure require reoperation [35]. Therefore, internal drainage is currently thought to be a dangerous and incomplete treatment. In contrast, complete BDD excision appears to be the standard treatment and can be performed safely either as a primary or a secondary procedure (after failure of internal drainage). Complete cyst excision means that the division of the biliary tract should be carried out in healthy biliary tissue, either at the superior and inferior part of the cystic component, with the use of frozen section pathological examination to rule out the presence of cancer [7]. Proximally, the involvement of main biliary convergence and/or of sectorial biliary ducts must be preoperatively or intraoperatively analyzed in order to prevent incomplete resection and reconstruction on non-healthy bile ducts. At their distal part, type I and IV BDD require excision of the intrapancreatic cystic portion down to the healthy distal bile duct [7]. In this setting, precise preoperative knowledge of ABPJ anatomy is a key factor to avoid intraoperative damage of the pancreatic duct or of the long common channel during cyst excision [7]. Biliary reconstruction can be performed using a long 70-cm defunctionalized Roux-en-Y jejunal loop with a wide bilio-digestive anastomosis at the level of the CBD or, more frequently, of the main biliary convergence after having extended the opening on the left hepatic duct (according to the Hepp-Couinaud technique) [7]. The success rate of Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy has been shown to be as high as 92 % [36]. This procedure has a reported complication rate of 7 %, compared with a complication rate of 42 % with hepaticoduodenostomy [37]. Early postoperative complications of cyst excision and hepaticoenterostomy include anastomotic leak and pancreatic fistula with injury to the pancreatic duct. Recently, many authors have reported success performing laparoscopic cyst excision and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy , with quicker recovery, reduced adhesions, and improved cosmesis and ease of surgery because of magnification of the operative field [35]. With the advent of robot-assisted surgery, which has improved manual dexterity, laparoscopic treatment of choledochal cyst is still evolving and promises further benefits [35].