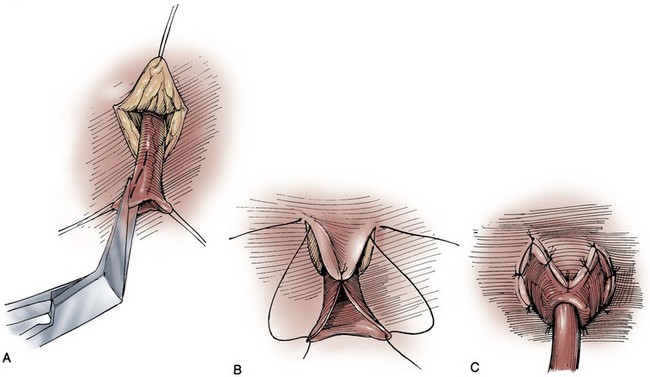

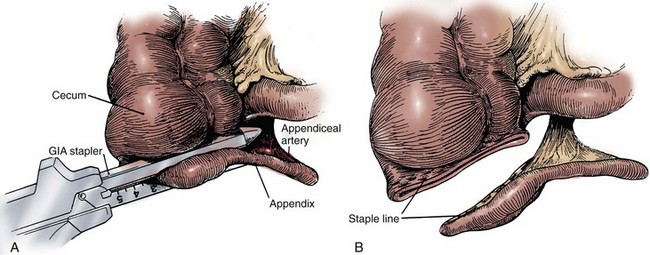

James M. McKiernan, MD, G. Joel DeCastro, MD, MPH, Mitchell C. Benson, MD Renal and hepatic function must be reviewed carefully in the patient selected for continent diversion (Mills and Studer, 1999). The reabsorption and recirculation of urinary constituents and other metabolites require that liver function be normal and that serum creatinine levels be within normal range, or certainly below the level of 1.8 mg/dL. In cases in which renal function is borderline, creatinine clearance should be measured. A minimal level of 60 mL/min should be documented before deeming the patient an appropriate candidate for continent diversion. In patients with bilateral hydronephrosis in whom renal functional improvement might be anticipated on relief of the ureteral obstruction, the upper urinary tract should first be decompressed with either ureteral stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy(ies). Subsequent reevaluation of renal function should be performed before undertaking a continent diversion. In constructing a nonappendiceal continent urinary diversion stoma, a skin button matching the diameter of the structure to be used in the diversion is resected. Cutaneous tissues are separated down to the level of the anterior rectus fascia, where a circle of similar diameter is excised from this fascia or, alternatively, the fascia is incised in a cruciate fashion. In carrying out this maneuver, it is essential that the fascia and skin are properly aligned in order to avoid angulation. Rectus muscle fibers are separated bluntly and an instrument passed through the posterior fascia and peritoneum. For appendiceal stomas, we prefer to perform a Y-shaped cutaneous incision that allows for a YV-type plasty incision between the appendiceal limb and the skin (Fig. 86–1). This will decrease the likelihood of subsequent stomal stenosis. Alternatively, the appendix lends itself to an umbilical stoma (Bissada, 1993; Gerharz et al, 1997). Favorable results with this appendiceal YV plasty technique to the umbilical site have been reported (Bissada, 1998). (From Hinman F Jr. Atlas of urologic surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1989.) Paralytic ileus is a common complication following urinary diversion procedures. Gastric decompression should be maintained until extubation. This can be achieved in the majority of patients by means of nasogastric intubation. However, certain patients may be managed best by formal gastrostomy decompression inserted intraoperatively. These individuals include those with multiple prior abdominal procedures in whom prolonged ileus is more likely. If the patient is nutritionally depleted preoperatively, hyperalimentation has been suggested to be of value if initiated during the preoperative interval (Hensle, 1983; Askanazi et al, 1985). Late malignancy has been reported in all bowel segments exposed to the urinary stream, whether or not there is a commingling with feces (Filmer and Spencer, 1990; Shokeir et al, 1995). A study by Gitlin and colleagues (1999) suggests that the malignancy may develop from the urothelial component and not as a result of urine affecting intestinal mucosa. As a result, urinary cytology should be performed in all patients undergoing a continent urinary diversion whether or not the diversion was performed secondary to a urothelial malignancy. When the ureters are directed into the fecal stream, routine colonoscopy should also be performed. Latency periods have been reported as short as 5 years, so all patients developing gross or microscopic hematuria should be fully evaluated (Golomb et al, 1989). If an anastomotic transitional cell cancer is discovered, the patient should be fully evaluated with upper tract imaging and ureteroscopy if possible. Antegrade ureteropyeloscopy can be employed if necessary. For an isolated anastomotic recurrence, distal ureterectomy and reimplantation may be appropriate. If nephroureterectomy is necessary, some patients may require removal of their continent diversion due to resulting renal insufficiency. The concept of refashioning bowel so that it serves as a urinary reservoir rather than a conduit has become universally accepted. This concept is based on original pioneering observations by Goodwin and colleagues in the development of the cystoplasty augmentation procedure (Goodwin et al, 1958). The destruction of peristaltic integrity and refashioning of bowel has led to the development of many innovative urinary reservoirs constructed from bowel. Several antireflux procedures have evolved to avoid upper tract urinary damage by sepsis or reflux, while other surgical techniques have been devised to achieve urinary continence. It should be re-emphasized that all continent diversions will allow for substantial reabsorption of urinary constituents that will place an increased workload on the kidneys (Mills and Studer, 1999). No patient with substantial renal impairment should be considered for any of these procedures. The long-term sequelae of continent urinary diversion are well understood and, unfortunately, commonly involve significant renal damage. Although it has been suggested that the absence of reflux into the upper urinary tracts in catheterizable pouches may reduce the long-term impact of continent diversion procedures on renal function, it should be cautioned that long-term 15-year data are now available and, in some instances, antireflux procedures are associated with a higher risk of obstruction due to anastomotic stricture (Kristjansson et al, 1995). In addition to increased stricture rates, it is not clear whether antirefluxing mechanisms actually result in improved preservation of the upper tracts (Pantuck et al, 2000). Multiple international studies have suggested an improved psychosocial adjustment of patients undergoing continent urinary and fecal diversion compared with those patients with diversions requiring collecting appliances (Gerber, 1980; McLeod and Fazio, 1984; Boyd et al, 1987; Salter, 1992a, 1992b; Bjerre et al, 1995; Filipas et al, 1997; Hart et al, 1999; McGuire et al, 2000). Although this is indeed true and is best exemplified by the individual with a conduit who desires conversion to a continent procedure, it is also true that many individuals seem to adjust well to wearing external appliances. The sense of body image is a remarkably personal and subjective parameter that varies greatly from patient to patient. In fact, the majority of patients are satisfied with their choice of urinary diversion, whether it is continent or not. The process of patient counseling that we employ always refers to ileal conduit diversion as the gold standard against which the newer, more complex operations must be compared. The patient should be advised that continent diversion is, all other considerations being equal, associated with a longer hospital stay, higher complication rates, and greater potential for requiring reoperative surgery. However, it should be noted that an extensive review from our institution has demonstrated no statistically significant difference in reoperations, mortality, or hospital stay in patients undergoing continent diversion versus conduit diversion by the same three surgeons over a 3-year period (Benson et al, 1992). Analysis of the two patient groups, on the other hand, showed that, in general, those selected for continent diversion were 12 years younger and four times less likely to have significant concurrent illness. What this review suggests is that, with proper patient selection, continent diversion operations can be safely conducted with results similar to those for conduit diversion. To determine if continent diversion could be safely performed in selected elderly patients, Navon and colleagues (1995) compared the clinical course of 25 patients older than the age of 75 years undergoing a modified Indiana reservoir to a cohort of 25 randomly selected patients younger than 75. The mean age of the first group was 78.5 years, and the mean age of the second was 59.3 years. The complication rates between the two groups were acceptably low and surprisingly similar. Navon and colleagues concluded that age alone should not be a contraindication to continent diversion and that the Indiana reservoir can be successfully performed in elderly patients. Various innovative surgical techniques have been advocated for separating the fecal and urinary streams, while still employing the principles of ureterosigmoidostomy. These operations can generally be discussed together as rectal bladder urinary diversions. In each of these operations the ureters are transplanted into the rectal stump. The proximal sigmoid colon is managed by terminal sigmoid colostomy or, more commonly, by bringing the sigmoid to the perineum, thereby using the anal sphincter to achieve both bowel and urinary control. Although these operations continue to be commonly performed, they have never been well accepted in the United States. The principal reason is the potential for the calamitous complication of combined urinary and fecal incontinence, presumably occurring as a consequence of damage to the anal sphincter mechanism during the dissection processes (Culp, 1984). If the urologist selects one of these procedures, the preoperative evaluation should include all of the caveats of ureterosigmoidostomy. Dilated ureters are not acceptable. Patients with extensive pelvic irradiation are not candidates, and neither are those with existing renal insufficiency. Anal sphincteric tone must be judged competent before electing these operations. Our preference has been to use a 400- to 500-mL thin mixture of oatmeal and water that the patient is asked to retain for 1 hour in the upright position (Spirnak and Caldamone, 1986). Finally, colonoscopy must be carried out before the procedure to rule out pre-existing colorectal disease, as well as after the procedure to guard against the potential development of colonic cancer. Procedures that separate the fecal and urinary streams but drain both through the rectal sphincter are not described here. Those wishing a detailed description of these procedures can find them in prior editions of this chapter. The following is a brief description of more modern surgical procedures that use the intact anal sphincter for urinary and fecal continence. However, the surgical techniques for these procedures will likewise not be discussed in this edition. A modification of the ureterointestinal anastomosis was described by a group from Mansoura, Egypt (Hafez et al, 1995; El-Mekresh et al, 1997). This procedure creates a folded rectosigmoid bladder with anastomosis of the ureters via serosa-lined tunnels rather than into the taenia coli. This procedure has the advantage of a larger sigmoid reservoir, as well as the prevention of reflux by creating the above serous-lined tunnel for the anastomosis. This reimplantation technique was first described by Abol-Enein and Ghoneim (1993) and appears to have a lower complication rate than direct taenial implantation (Hafez et al, 1995). Patients undergoing this procedure must be closely monitored for the development of hyperchloremic acidosis. This will occur in the majority of cases, and it is wise to initiate a bicarbonate replacement program following the operation. Because hypokalemia is also a feature of ureterosigmoidostomy, replacement of potassium along with bicarbonate may be achieved with oral potassium citrate. Routine nightly insertion of a rectal tube is advocated in the long-term care of the patient. However, many patients will reject this practice as uncomfortable and unappealing. Nighttime urinary drainage should be mandated in any patient who cannot maintain electrolyte homeostasis with oral medication. Bissada and colleagues (1995) reported that 30 of 61 patients were able to stay dry during the night without awakening. The other 31 required two or more awakenings to remain dry overnight. Hyperchloremic acidosis was reported in 4 of 61 noncompliant patients. In 1997 El-Mekresh and colleagues (1997) reported on 64 patients (32 women, 20 men, and 12 children) who underwent their rectosigmoid bladder procedure between 1992 and 1995. Follow-up ranged from 6 to 36 months. Functional results were assessable in 57 patients: 1 died of a postoperative pulmonary embolism and 6 died from their disease. All patients were continent during the day with two to four emptyings, whereas all but four remained dry at night with zero to two emptyings. Four children experienced enuresis that responded to 25 mg of imipramine at bedtime. Importantly, upper urinary tract function was maintained or improved in 95% of patients. However, six renal units (5.3%) developed obstructive hydronephrosis secondary to ureterocolic anastomotic strictures. Two were remedied by antegrade dilation, one was repaired by open revision, and one nonfunctioning renal unit was removed. The fate of the remaining two units was not specified. No patient in this series developed a postoperative metabolic acidosis. However, all patients were maintained on prophylactic oral alkalinization. Obviously, all patients undergoing these procedures have exposure of the urinary tract to fecal flora. Most authors would advocate chronic administration of an antibacterial agent in all patients (Duckett and Gazak, 1983; Spirnak and Caldamone, 1986). Ureteral strictures require reoperative surgery and are experienced in 26% to 35% of cases over time (Williams et al, 1969; Duckett and Gazak, 1983). Because of the concern for development of rectal cancer anywhere between 5 and 50 years (average 21 years) after ureterosigmoidostomy (Ambrose, 1983), it is suggested that patients with long-term ureterosigmoidostomy undergo annual colonoscopy (Filmer and Spencer, 1990). Barium enemas are relatively contraindicated because reflux of this material into the kidneys (if the antireflux procedure fails) can result in dire consequences (Williams, 1984). Additional methods for colon carcinoma screening in this population are the evaluation of stool for blood, and the attempted cytologic examination of the mixed urine and feces specimen (Filmer and Spencer, 1990). Kock developed this technique to be used in locales where stoma appliances were not readily available (Kock et al, 1988). This operation is similar to standard ureterosigmoidostomy except that a proximal intussusception of the sigmoid colon confines the urine to a smaller surface area, thus minimizing the problems of electrolyte imbalance. Additionally the rectum is patched with ileum to improve the urodynamic properties of the rectum as a urinary reservoir. Preoperative evaluation is similar to that used in ureterosigmoidostomy. The large bowel must be studied for pre-existing disease, and anal sphincteric integrity must be tested before surgery. In his description of the augmented valved rectum procedure, Kock described the use of a foreshortened hemi-Kock pouch to be used as a rectal patch when the ureters were too dilated to bring down between the leaves of the intussuscepted sigmoid (Kock et al, 1988). Skinner then modified this procedure by using an entire hemi-Kock segment to augment the rectum after sigmoid intussusception (Skinner et al, 1989). After extensive experience with the Kock ileal reservoir, the group at the University of Southern California has attempted to improve on the intussuscepted Kock continence mechanism. The result has been the modification of the T pouch to serve as an ileal anal reservoir (Stein et al, 1999a). The technique consists of the construction of a hemi-Kock or T pouch employing doubly folded, marsupialized ileum and a proximal continence mechanism to prevent pouch-ureteral reflux. This pouch is then anastomosed to the rectum directly as a patch. Contact of urine with the proximal colon can be avoided by the intussusception of the sigmoid colon proximal to the anastomotic site (Fig. 86–2). (From Stein JP, Buscarini M, DeFilippo RE, Skinner DG. Application of the T pouch as an ileo-anal reservoir. J Urol 1999;162:2052–3.) Skinner and colleagues reported on the results of the hemi-Kock procedure in 15 patients between 1987 and 1991 (Simoneau and Skinner, 1995). Four patients had prior bladder exstrophy and were converted to an ileoanal reservoir, and 11 patients underwent the procedure as a form of primary diversion after cystectomy. At the time of the report 10 patients were still alive and could be evaluated. Early postoperative complications occurred in three patients (20%): a colocutaneous fistula in two patients, urine leak in one, and deep venous thrombosis in another. Late complications included partial small bowel obstruction in four patients (with two requiring surgery), urinary retention requiring surgery in two patients, and metabolic acidosis in five patients. Two of the 11 patients undergoing primary construction never achieved continence; both were older than 68 years. The authors summarized their experience by concluding that the operation is best suited for the younger exstrophy patient and that it is essential to avoid colonic redundancy distal to the reservoir. The use of the T pouch as an ileoanal reservoir has been reported in one former exstrophy patient (Stein et al, 1999a), with no reported postoperative complications. A variation of ureterosigmoidostomy was described by Fisch and Hohenfellner in 1991 and updated in 1996 (Fisch and Hohenfellner, 1991; Fisch et al, 1996). This operation, which they termed the sigma rectum or the Mainz II pouch, creates a low-pressure rectosigmoid reservoir of increased capacity. They viewed the simplicity and reproducibility of the operation as one of its major advantages. Woodhouse and Christofides (1998) reported on their experience with the Mainz II pouch in 15 primary cystectomy patients and 4 patients with prior standard ureterosigmoidostomy who were incontinent. They reported excellent results: 14 of 15 (93.3%) of the primary patients achieved documented daytime and nighttime urinary control, while the remaining patient refused follow-up but reported continence. The four patients undergoing a salvage procedure fared less well. Only two patients became continent, while the remaining two were found to be in chronic retention. Their failed continence was believed to be secondary to inadequate pouch emptying. Similarly, excellent results have been achieved by Venn and Mundy (1999). They reported full daytime and nighttime urinary continence in 14 of 14 patients and no major postoperative complications. Bastian and colleagues (2004) have reported on the health-related quality of life in 83 patients undergoing Mainz II urinary diversion. They found that quality of life was similar to that of age-matched controls except for diarrhea symptoms, with 100% daytime continence. Numerous operative techniques have been developed for continent diversion wherein urine is emptied at intervals by clean intermittent self-catheterization. Many of these operations are described in this chapter, although certain pioneering procedures that used intact bowel (e.g., those of Gilchrist and colleagues [1950], Ashken [1987], Mansson and colleagues [1984, 1987], Benchekroun [1987]) are not. This is not to discredit the pioneers in the field but simply to allow this chapter to focus on those pouches that incorporate modern principles that attempt to achieve a spherical configuration and disruption of peristalsis. Before the extension of orthotopic neobladder construction to women, there was some enthusiasm for the orthotopic placement of a catheterizing portal. This procedure has been carried out in certain female patients with success. The construction of a neourethra to the introitus is attractive, provided there is no substantial difficulty in the catheterizing process. Because it can be difficult to direct a catheter through the “chimney” of an intussuscepted nipple valve, those continent diversions employing nipple valves are not particularly adaptable to orthotopic location, although they have been performed with success in a small number of patients (Olsson, 1987). In contrast, the imbricated and tapered ileal segment leading to an Indiana pouch is relatively easier to catheterize and can be used for orthotopic catheterizing diversion (Rowland et al, 1987). However, it may be difficult to obtain sufficient mesenteric length in some patients. The appendix can also be used as a neourethra, in which case mesenteric length should become less of a problem (Hubner and Pfluger, 1995). Four general techniques have been employed to create a dependable, catheterizable continence zone. For right colon pouches, appendiceal techniques, pseudoappendiceal tubes fashioned from ileum or right colon, and the ileocecal valve plication are applicable. Appendiceal tunneling procedures are the simplest of all to perform because they use established surgical techniques already present in the urologic armamentarium. The in situ or transposed appendix is tunneled into the cecal taenia in a fashion similar to ureterocolonic anastomosis. Appendiceal continence mechanisms have been criticized for three general reasons. First, the appendix may be unavailable in some patients because of prior appendectomy. For those individuals, techniques have been developed that allow for the construction of a similar tube fashioned from ileum (Woodhouse and MacNeily, 1994) or from the wall of the right colon (Lampel et al, 1995a). Second, the appendiceal stump may be too short to reach the anterior abdominal wall or umbilicus while still maintaining sufficient length for tunneling. This criticism has been addressed by an operative variation described by Mitchell, in which the appendiceal stump can be lengthened by the inclusion of a tubular portion of proximal cecum (Burns and Mitchell, 1990) (Fig. 86–3). This lengthening procedure has the added advantage of allowing for a slightly larger stoma made of cecum that is less prone to stomal stenosis. Appendiceal continence mechanisms share the feature of allowing only small-diameter (14- to 16-Fr) catheters to be used for intermittent catheterization, whereas the large amount of mucus produced by an intestinal reservoir is more easily emptied or irrigated using a 20- to 22-Fr catheter. We believe that these criticisms are more theoretical and that the appendiceal or pseudoappendiceal continence mechanism remains an attractive and reliable continence mechanism. (From Burns MW, Mitchell ME. Tips on constructing the Mitrofanoff appendiceal stoma. Contemp Urol 1990;May:10–2.) The second major type of continence mechanism used in right colon pouches is the tapered and/or imbricated terminal ileum and ileocecal valve. Here again the technology is rather simple, with imbrication or plication of the ileocecal valve region along with tapering of the more proximal ileum in the fashion of a neourethra (Rowland et al, 1985; Lockhart, 1987; Bejany and Politano, 1988). These techniques afford a reliable continence mechanism. The third surgical principle used in constructing the continence mechanism is the use of the intussuscepted nipple valve or, more recently, the flap valve, which avoids the need for intussusception. The creation of nipple valves is by far the most technologically demanding of all the continence mechanisms, and it is associated with the highest complication and reoperation rates. There exists a significant learning curve before the surgeon achieves reproducible and dependable results. For this reason, nipple valve construction should probably not be chosen by the surgeon carrying out occasional construction of continent pouches. Furthermore, it should be noted that in the past 2 decades we have seen the introduction of numerous modifications of the original technique of Kock for construction of a stable nipple valve. The singular reason for all of these modifications is the rather disappointing long-term stability of the nipple valve in some patients. As a result, the group at the University of Southern California has developed the T pouch, which uses a flap valve (Stein et al, 1998). This procedure, which appears much simpler than the intussuscepted nipple valve, has been used to create both a continence and an antireflux mechanism. Nipple valve failure from slippage or valve effacement can be anticipated in 10% to 15% of cases even in the hands of the best and experienced surgeons. In addition to slippage, nipple valves are subject to ischemic atrophy. When this occurs, a new nipple valve must be fashioned from a new bowel segment. A final feature of stapled nipple valves is the potential for stone formation on exposed staples. This was greatly lessened by the omission of staples at the tip of the intussuscepted nipple valve, as suggested by Skinner and colleagues (1984). However, more proximal staples occasionally erode into the pouch and serve as a nidus for stone formation. These stones are usually manageable endoscopically with forceps extraction or else with electrohydraulic or ultrasonic disintegration of the stone with subsequent forceps extraction of the staple. Although exposed staples may serve as a nidus for stone formation, continent urinary diversion in and of itself results in more urinary excretion of calcium, magnesium, and phosphate as compared with ileal conduit diversion (Terai et al, 1995). Thus all patients undergoing continent diversion are at an increased risk for the formation of reservoir stones. The fourth major technique of continence mechanism construction is the provision of a hydraulic valve, as in the Benchekroun nipple (1987). In this procedure a small bowel segment is isolated, with subsequent reversed intussusception that effectively apposes the mucosal surfaces of the segment. Tacking sutures are placed on a portion of the circumference of the intussuscepted segment in order to stabilize the nipple valve while allowing urine to flow freely between the leaves of apposed ileal mucosa. As the pouch fills, hydraulic pressure closes the leaves, thereby ensuring continence. The premise of this technique is that as the reservoir fills, the pressure within the valve would also increase, resulting in continence. Concerns regarding stomal stenosis, especially in children, and nipple destabilization have resulted in this procedure being largely abandoned (Sanda et al, 1995). As a result, it is not discussed in this chapter. The following represents a summary of common patient questions and everyday solutions: Because all patients with catheterized pouches will have chronic bacteriuria, the problem of antibiotic management should be discussed. Most authors would suggest that bacteriuria in the absence of symptomatology does not warrant antibiotic treatment (Skinner et al, 1987). The construction of an effective antireflux mechanism in these pouches may help protect against clinical episodes of pyelonephritis, in contrast to patients with freely refluxing conduits. Obviously, if clinical pyelonephritis does occur, antibiotic treatment should be instituted. Episodes of recurrent pyelonephritis should be evaluated with radiography of the pouch in order to diagnose failure of the antireflux mechanism or upper tract stone formation. Urinary retention is an infrequent but serious occurrence in catheterizable pouches.

General Considerations

Patient Preparation

Cystectomy

Postoperative Care and Comments

Continent Urinary Diversion

Rectal Bladder Urinary Diversion

Folded Rectosigmoid Bladder

Postoperative Care and Comments

Augmented Valved Rectum

Hemi-Kock and T Pouch Procedures with Valved Rectum

Postoperative Care and Comments

Sigma-Rectum Pouch, Mainz II

Postoperative Care and Comments

Continent Catheterizing Pouches

General Procedural Methodology

General Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cutaneous Continent Urinary Diversion

• What kind of catheter do I use? For nipple valves, a straight-ended 22- to 24-Fr tube; for ileocecal plication, a 20- to 22-Fr coudé tip catheter; and for appendiceal sphincters, a 14- to 16-Fr coudé tip catheter.