Crohn’s Disease and Indeterminate Colitis

Victor W. Fazio

The knife cannot always have fresh fields for conquest; and although methods of practice may be modified and varied, and even improved to some extent, it must be within a certain limit.

–SIR JOHN ERICHSEN, Lancet. 1873;2:489

▶ CROHN’S DISEASE

Crohn’s disease of the bowel was initially described by Crohn, Ginzburg, and Oppenheimer in 1932, at which time they noted a transmural inflammatory condition of the terminal ileum.96 The authors apparently listed their names in alphabetical order for the purpose of publication. It would certainly appear that if one is concerned about eponymous immortality, it is helpful to have a name occurring early in the alphabet. Interestingly, many of the cases were based on the large patient experience of Berg.340 Had Dr. Berg wished to include his name on the paper, the condition today would probably be termed Berg’s disease. Ginzburg reflected on the myths and misunderstandings concerning the evolution of the concept of Crohn’s disease in his interesting paper “The Road to Regional Enteritis.”180 A number of publications followed from the experience of Crohn and his associates, confirming the location in the small bowel, but also noting that in a number of cases the colon was to some extent involved.

Another interesting historical footnote was suggested by Goligher189 that Crohn’s disease was actually initially described in 1907 by Lord Moynihan when Moynihan presented his experience with six patients who harbored benign lesions that mimicked carcinoma.368 In 1913, Dalziel reported an obscure tuberculosis-like condition that he called “chronic interstitial enteritis” but which must have been Crohn’s disease.99 In 1923, Moschowitz and Wilensky described four patients with a granulomatous disease of the intestine and the amelioration of the condition by intestinal bypass.366

In 1951, Marshak noted the radiologic findings of what he felt was granulomatous disease of the colon, a clinical entity distinct from that of ulcerative colitis.340 This view was not generally accepted until 1959, when Morson and Lockhart-Mummery described the characteristic pathologic features of granulomatous colitis.364 It can be appreciated, therefore, that our concepts of disease involvement in this area are scarcely one-half century old.

Incidence, Epidemiology, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

The incidence, epidemiology, and theories concerning the etiology and pathogenesis of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are discussed in Chapter 29. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) remains a complex polygenic disorder interacting with environmental factors that trigger abnormal responses in genetically susceptible individuals.394 The incidence of IBD development in identical twins is 60% in Crohn’s but only 15% in ulcerative colitis.483 Subclinical intestinal inflammation has also been documented in symptomatic first-degree relatives of Crohn’s disease patients.

It is interesting to note that Mycobacterium paratuberculosis DNA has been found in Crohn’s diseased tissue.482 The concept of a bacterial cause for IBD has been discussed in Chapter 29, an issue that has generally been refuted. In one study, however, M. paratuberculosis was identified in 65% of specimens in individuals with Crohn’s disease but in only 4.3% of those with ulcerative colitis.482 The control tissues were found to have this DNA element in 12.5%. It was concluded that these observations are consistent with an etiologic role for M. paratuberculosis in Crohn’s disease. A statistically significant association between the onset of Crohn’s disease and prior antibiotic use has been demonstrated.75 This suggests that a change in the bacterial environment within the intestinal tract in a susceptible host may be responsible for triggering the disease in some patients. Smokers are also overrepresented in Crohn’s patients and underrepresented in ulcerative colitis, and they have an increased risk of recurrence after surgery when compared with nonsmokers.598,603

BURRILL BERNARD CROHN (1884-1983)

|

Burrill Crohn was born in New York City, June 13, 1884. He graduated from the City College of New York in 1902 and received his medical degree from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1907. Crohn began his internship at Mount Sinai Hospital, the institution with which he was affiliated for his entire professional life. In 1920, he was named the first head of the department of gastroenterology. Henry Janowitz wrote that the “eponym [of Crohn’s disease] is deserved not because of a fortuitous alphabetical listing, but because for many years Crohn alone called attention to this enigmatic inflammation of the bowel, by carefully collecting cases and by publishing his clinical observations.” Janowitz further stated that although not displeased with the honor and the name recognition, Crohn was always modest with respect to his role in the original description. Crohn himself expressed the feeling that the name Crohn’s disease was inappropriate despite its virtually universal use, preferring instead the term regional enteritis. In 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower required surgery for ileitis, it was Crohn who was called to the White House to act as spokesman to explain the disease and the prognosis to the American people. Crohn authored three texts and more than 100 scientific papers. Among his numerous awards were the Townsend Harris Medal by the City College of New York, the Julius Friedenthal Medal of the American Gastroenterological Association, and the Mount Sinai Hospital’s Jacobi Medal. He was also elected president of the American Gastroenterological Association. Crohn died in New Milford, Connecticut, at the age of 99.

LEON GINZBURG (1899-1988)

|

Leon Ginzburg was born in Bayonne, New Jersey. He completed his undergraduate studies at Columbia University in 1920 and went on to accomplish his surgical training at the Mount Sinai Hospital. Following a tour of the major European institutions, he returned to become A. A. Berg’s House Surgeon at Mount Sinai. For the ensuing 5 years, he was an adjunct on Berg’s ward service and his assistant in the private practice of surgery. The association with Mount Sinai lasted for 40 years, with Ginzburg achieving the rank of clinical professor. From 1947 to 1967, he was director of surgery at the Beth Israel Hospital, as the medical center was then known. The recognition of ileitis was accomplished by examining surgically excised specimens, which led in 1927 to his first description. There was a well-recognized controversy between Ginzburg and Crohn concerning each individual’s respective role in the early observations. As both physicians neared their 90s, Ginzburg compared the discovery of regional ileitis to the controversy over the naming of the United States after Amerigo Vespucci rather than after Christopher Columbus. He likened the former map maker to Crohn, who spent considerable time and effort traveling, lecturing, and spreading knowledge about the disease, while he credited himself with the original description. Leon Ginzburg was active in practice at Beth Israel Medical Center until his death in 1988 at the age of 89. (With special appreciation to Lester Rosen, MD.)

GORDON DAVID OPPENHEIMER (1900-1974)

|

Gordon Oppenheimer was born on June 30, 1900, in New York City and received his baccalaureate from Columbia College in 1919, and his medical degree from Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1922. He then became a house officer at the Mount Sinai Hospital, eventually entering the pathology laboratory where he collaborated with Ginzburg in his work on the study of inflammatory lesions of the terminal ileum. Oppenheimer ultimately became a urologist, rising to the position of Chief of Urology at Mount Sinai Hospital, a post he occupied from 1947 to 1963. He authored 69 papers, including a monograph he published with Leon Ginzburg, Urological Complications of Regional Ileitis. In addition to his responsibilities as chairman of the department and director of the residency program, Oppenheimer found time to serve for 14 years as a medical officer with the New York City Fire Department. During World War II, he acted as Second in Command of the General Surgical Service at Mount Sinai Hospital. He is remembered as a kind, gentle, and humble man, an especially humane physician who was much sought after as a consultant urologist. He died of cardiac failure, December 9, 1974, at the age of 74.

ALBERT ASHTON BERG (1872-1950)

|

It might seem incongruous that I have elected to include A. A. Berg as an individual to be recognized with a biographic sketch in this text. But he represents for me a special person—someone who could afford the “luxury of integrity.” Berg declined to add his name to the alphabetical listing of coauthors because, even though the publication was based on his surgical patients, he did not contribute to the writing. He was born in New York City, August 10, 1872, and attended City College of New York, graduating from the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University in 1894. After his surgical training at the Mount Sinai Hospital, he joined the staff. In his early years, he was an assistant to Arpad Gerster, the man who introduced Listerian principles to the United States. Berg developed an enormous clinical practice, arguably the largest in the city of New York, having been recognized as a phenomenal technician. He is credited with having performed the first gastrectomy for ulcer disease in the United States. In 1930, he published his experiences with more than 500 patients on the morbidity and mortality of subtotal gastrectomy in the management of gastric and duodenal ulcer. In 1905, he published a text, Surgical Diagnosis: A Manual for Students and Practitioners. In 1934, when he retired from the teaching service at Mount Sinai, the hospital published The Surgical Technique of Dr. A.A. Berg: A Tribute to Forty Years’ Service at the Mt. Sinai Hospital. The chapters were written by his students, including contributions on the small bowel and colon by Leon Ginzburg. Along with his brother (an internist), he amassed a library of 50,000 rare volumes of English and American literature, bequeathing the collection to New York University, Mount Sinai Hospital, and the New York Public Library. Today there exists at Mount Sinai a Berg Laboratory Building and an Institute for Research, and at the New York Public Library, a Berg Room, where the collection is housed. Albert Berg died following kidney surgery on July 1, 1959, at the age of 77.

BERKELEY GEORGE ANDREW MOYNIHAN (1865-1936)

|

Berkeley Moynihan was born on the island of Malta, the only son of a distinguished army captain. He received his premedical education at the Royal Naval School and his medical training at the Leeds Medical School (1885) and at the University of London (1887). In 1893, he was awarded a gold medal in the examination for master of surgery. In 1895, he married the daughter of T. R. Jessop, the man who preceded him as surgeon to the Leeds General Infirmary. Moynihan was a masterful surgeon, particularly for surgery of the abdomen. He served as professor of surgery from 1902, becoming emeritus professor in 1926. In 1905, he published his outstanding book, Abdominal Operations, which ran through four editions. Among his numerous contributions and distinctions were founder and editor of the British Journal of Surgery, president of the Royal College of Surgeons, Hunterian Professor, and successively, knight, baronet, and baron.

THOMAS KENNEDY DALZIEL (1861-1924)

|

T. Kennedy Dalziel (pronounced “dee-yell”) was born in Scotland at Merkland, Penpont, Dumfriesshire. He received his early education at a private school in Dumfries and studied medicine at Edinburgh University, graduating in 1883. He continued his medical studies in Berlin and Vienna, where he specialized in experimental surgery and pathology. In 1885, he began his practice in Glasgow, and in 1889, he joined the staff of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children. For his services in World War I to the Advisory Council of the Royal Army Medical Corps, the king conferred on him the honor of knighthood. His successes and the public position he attained were the result of an unusual combination of qualities—charm, kindliness, extraordinary teaching skills, and marvelous manipulative dexterity. He was considered the best technical surgeon in the West of Scotland. His contributions to the medical literature were considerable, dealing primarily with that of abdominal surgery.

RICHARD H. MARSHAK (1912-1982)

|

Richard Marshak received his MD with honors from the University of Louisville in 1937. After completing residencies in pathology and radiology, Marshak was invited by Burrill Crohn at Mount Sinai Hospital to join his private practice as a consulting radiologist. Consequently, Marshak saw hundreds of patients with gastrointestinal disorders. His unique forte consisted of correlating the pathologic findings of the gastrointestinal tract with the radiologic features. He, along with Bernard Wolf, elucidated the radiologic changes in esophagitis, hiatal hernia, and inflammatory bowel disease. Wolf’s collaborations, over a period of many years with Richard Marshak and Mansho Khilnani, on the physiologic and anatomic details of the esophagus and gastrointestinal tract and on the various aspects of inflammatory bowel disease, were unique. Much of what we take for granted today was first articulated during this era by these three men. Bernard Wolf, chairman of the department of radiology presented the Jacobi Medallion of the Alumni Association to Richard Marshak in 1972. Dick, as he was called, was the first president of the Society of Gastrointestinal Radiologists (SGR) and helped found the Health Insurance Plan. Before it became such a hot button, current topic, he pressed for the availability of medicine to everyone. He was the recipient of the Townsend Harris medal, given by the Alumni Association of the City College for outstanding achievements. He also received the Gold Medal Award from the Radiological Society of North America for distinction as an author, scholar, teacher, and scientist. Marshak was past president of the New York Academy of Gastroenterology, the New York Roentgen Society, and the American College of Gastroenterology. A dominant figure in radiology for more than 30 years, Richard H. Marshak belongs to a group of Mount Sinai physicians who are remembered equally for their scientific achievements and for their colorful personalities. Marshak finished his career as clinical professor of radiology at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, continuing to work steadily until his death in 1982. As a founding member and the first president of the former Society of Gastrointestinal Radiologists, Marshak is recognized for his spirit of leadership and dedication to the SGR. An annual award given in his memory, the Richard H. Marshak International Lecture is presented to a member of the Society of Abdominal Radiology who represents the organization at the International Education Conference held annually in a country that cannot support education in the field of abdominal radiology. An annual contribution of $4,000 is received from the Marshak Fund in support of this award.

When the ravages of diabetes resulted in Marshak’s almost complete loss of vision, with the assistance of his long-time associate, Daniel Maklansky, himself a gifted radiologist and teacher, Marshak continued to give lectures, describing in detail slides he could barely see. Richard Marshak died of a heart attack at Lenox Hill Hospital, December 20, 1982, at the age of 70. He died just before the publication of the last in a series of books he had written on gastrointestinal diseases. (Photograph courtesy of the Mount Sinai Archives.)

Another observation involves the identification of genes associated with IBD. Pokorny and associates identified a genetic and clinical association between the DNA repair gene, MLH1, and both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (see Chapter 29).412 Most exciting is the identification of the NOD2 gene (now renamed CARD15) as the IBD1 gene in the pericentromeric region of chromosome 16 which signals the opening of a vast arena of genetic research to provide a basic understanding of IBD.217,251,389 NOD2 is involved in the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor that plays a significant role in Crohn’s disease. NOD2 encodes a protein homologous to plant disease resistance genes that are involved in the immune response to infectious organisms, particularly the leucine-rich region that binds to bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Ten percent of Crohn’s patients have a frameshift mutation (via a cytosine insertion) that fails to induce NF-κB in the presence of bacterial lipopolysaccharide, suggesting a common link to the failure of immune response to bacterial components and thereby possibly explaining the role of antibiotics or the value of probiotics in the therapy of Crohn’s. Certainly, Crohn’s disease appears to be influenced by a wide range of genetic and environmental factors.522

Signs, Symptoms, and Presentations

Patients with Crohn’s disease may present with very minimal symptoms and moderate complaints, or they may have fulminant manifestations. The considerable overlap in the presentations of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is addressed in Chapter 29. For example, individuals with Crohn’s disease may bleed, but this is not as frequent a presentation and may not be as severe.349 However, life-threatening hemorrhage has been reported.85 Abdominal pain may be mild or absent in patients with ulcerative colitis, but those with Crohn’s disease frequently complain of pain. This may be colicky in nature and may be associated with intestinal obstruction, or it may be continual and related to the presence of a septic process within the abdomen. An abdominal mass is not uncommonly found on physical examination in a patient with Crohn’s disease, but it is never seen in a patient with ulcerative colitis.

Diarrhea is usually a more troublesome concern in patients with ulcerative colitis. This may be because distal disease

tends to be associated with more urgency, and in some cases, tenesmus. Patients with Crohn’s disease may have rectal sparing and are less likely to experience this urgency. Conversely, with rectal involvement, Crohn’s patients experience symptoms similar to those with ulcerative colitis. It is important to consider also the possibility of opportunistic infections and concomitant neoplasms, including cytomegaloviral infection and Kaposi’s sarcoma, especially in individuals with prolonged immunosuppressive therapy for this disease (see later, Medical Management).89

tends to be associated with more urgency, and in some cases, tenesmus. Patients with Crohn’s disease may have rectal sparing and are less likely to experience this urgency. Conversely, with rectal involvement, Crohn’s patients experience symptoms similar to those with ulcerative colitis. It is important to consider also the possibility of opportunistic infections and concomitant neoplasms, including cytomegaloviral infection and Kaposi’s sarcoma, especially in individuals with prolonged immunosuppressive therapy for this disease (see later, Medical Management).89

Anal disease is much more commonly seen in patients with Crohn’s colitis than in those with ulcerative colitis. The presence of anal pain, swelling, and discharge may be a presenting feature of the former condition and may be the only abnormality observed on examination and on subsequent investigation. In the experience of the Lahey Clinic group with anal complications in patients with Crohn’s disease, 22% of 1,098 were so afflicted.585 Anal fissure was diagnosed in 29% of patients who had anal manifestations; a fistula was found in 28%, an abscess in 23%, and multiple presentations in 20%. Crohn’s colitis was much more frequently associated with an anal lesion than was Crohn’s disease of the small bowel (52% vs. 14%). Within 1 year following the anal manifestation, Crohn’s disease presented elsewhere in 59% of patients. All the remaining developed gastrointestinal disease within 5 years. In the St. Mark’s Hospital experience, 34% of patients with small bowel Crohn’s disease had anal lesions, whereas 58% of those with colon disease were found to have anal involvement.321 Of 126 consecutive patients with perianal Crohn’s disease seen regularly in one outpatient clinic, 48% were diagnosed as having an abscess.332

A high level of suspicion should exist if the examiner notes characteristic edematous tags, blue discoloration of the skin, an eccentrically located fissure, a broad-based ulcer, a rigid or strictured canal, or an anal fistula, especially if the patient reports gastrointestinal symptoms. A clinical classification of perianal Crohn’s disease has been proposed by Hughes.248 The reader is referred to Chapters 13 and 14 for a discussion of the management of anal complications.

Fever is usually not a concern in patients with ulcerative colitis unless the patient is severely ill (e.g., toxic megacolon). However, in those with Crohn’s disease, a pyrexia is not uncommonly noted and is usually due to the presence of an intra-abdominal abscess or undrained septic focus. Nausea and vomiting are not frequently noted in either condition unless there is evidence of intestinal obstruction. Anorexia, weight loss, anemia, and general debility are associated with relatively long-standing or fulminant disease.

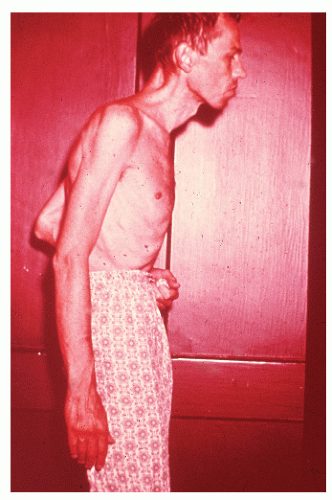

Disease in Children and Adolescents

When the condition occurs in children, there may be a more rapid onset and progression than when the disease occurs in young adults. These youngsters often become chronically ill, have growth impairment, have decreased mental acuity, and are less developed physically than their healthy peers (see Figure 29-26). It is because of these concerns that implementation of either an elemental diet or parenteral nutrition is an especially important part of the management in this age group (see Medical Management).267,481 However, in order to be maximally effective, therapy must be initiated before puberty.267 Furthermore, unless medical treatment can achieve a sustained remission, operative intervention may be the only effective means for addressing the problem of retarded development (see later).119

Elliott and colleagues reported the prognosis of 57 patients with Crohn’s disease of the large bowel seen within 6 months of the onset of symptoms during 1969 to 1978 and followed until 1984 at St. Mark’s Hospital.133 The cumulative probability of an operation was 35% at 5 years and 39% at 10 years. They concluded that about one-half of all such patients can be treated successfully without abdominal surgery. However, children and adolescents with colonic disease are much more likely to require resection, often after a relatively short period of illness.171,432 Growth retardation as an indication for surgery may be one of the reasons for this difference.

As with adults, the efficacy of surgery for Crohn’s disease in children seems to depend mainly on disease location and perhaps the choice of surgical procedure itself.101 Assessment of growth and development, psychological support for both the patient and the family, and close cooperation between the physician and the surgeon are important concepts in the management of these young people.449,455,481

Physical Examination

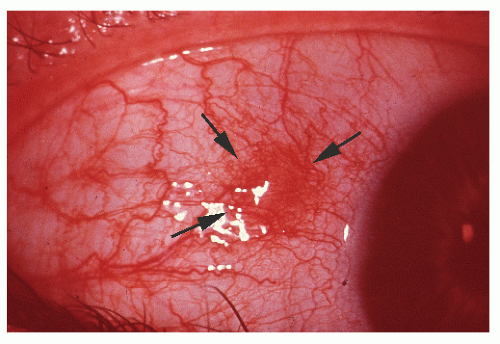

In contrast to individuals with ulcerative colitis, even in the absence of toxic megacolon, a patient with Crohn’s disease may demonstrate obvious findings on physical examination. As mentioned, although it is true that anorectal disease can occur with ulcerative colitis, it is much more common in those with Crohn’s disease. The diagnosis is often suspected on examination of the perianal skin (see Figure 14-51). Simple inspection will often show the edematous tags, fissures, abscess, or fistulas characteristically seen in this condition. The anal canal may be stenotic, fibrotic, and thickened on digital examination. If an anal fissure is apparent, severe pain is noted (Figure 30-1).

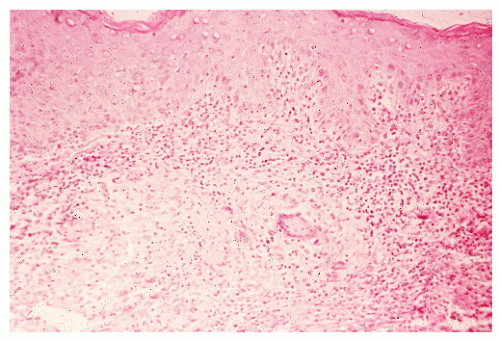

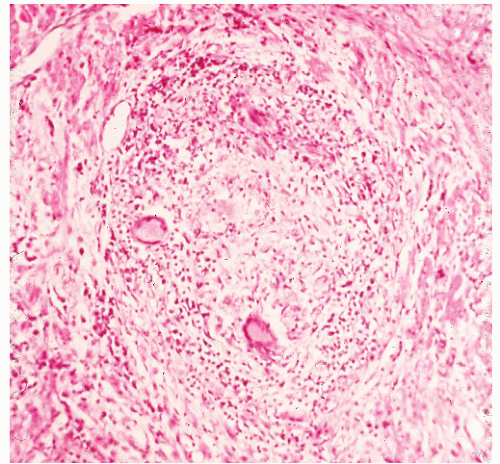

Pelvic examination in a woman may reveal a rectovaginal fistula, and bimanual examination may show the presence of a pelvic mass. A biopsy of a sinus tract or an abscess cavity may demonstrate the granulomas characteristic of Crohn’s colitis (Figure 30-2).

Pelvic examination in a woman may reveal a rectovaginal fistula, and bimanual examination may show the presence of a pelvic mass. A biopsy of a sinus tract or an abscess cavity may demonstrate the granulomas characteristic of Crohn’s colitis (Figure 30-2).

Abdominal findings are more common in patients with Crohn’s disease than in those with ulcerative colitis. A mass may be felt in the right iliac fossa, a common observation when regional enteritis involves the terminal ileum. A large, mesenteric abscess can often be palpated. Crohn’s colitis, however, usually is not associated with clinically demonstrable abdominal abnormalities.

Endoscopic Examination

Proctosigmoidoscopic examination is often helpful in differentiating between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The rectum is always diseased during attacks of ulcerative colitis, whereas with Crohn’s colitis, 40% of patients have sparing of the rectum, irrespective of anal or perianal involvement (see Chapter 29). But when the rectum is involved by Crohn’s disease, differentiation between the two may be quite difficult.

A corollary to this observation is to perform biopsies distal to obvious inflammatory changes if the rectum appears to be spared because one may discover that the rectum is not truly normal. This may cause the physician to reassess the accuracy of a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease for what was initially thought to be lack of rectal involvement. Biopsy may be helpful because histologic changes suggestive of Crohn’s disease in particular may be apparent. Up to 20% of such patients may exhibit granulomata.

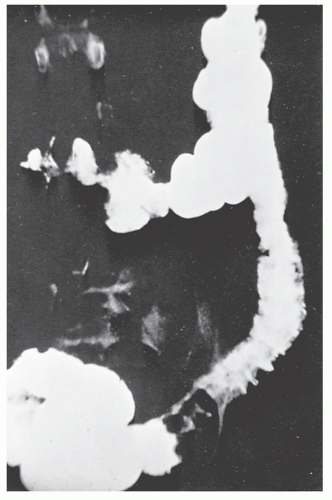

The place of colonoscopy in the evaluation and followup of IBD has been extensively reviewed by many authors. Teague and Waye recommend colonoscopy for five indications: differential diagnosis, resolution of radiographic abnormalities (e.g., filling defects and strictures), preoperative and postoperative evaluation in Crohn’s disease, examination of stomas, and screening for premalignant and malignant changes.546 With granulomatous colitis, Waye observed the following major colonoscopic findings: a normal rectum (obviously this is not always the case), asymmetry or eccentricity of involvement, cobblestone appearance, normal vasculature, edema of the bowel wall (as seen in ulcerative colitis), normal mucosa intervening between areas of ulceration, serpiginous ulcers (these may course for several centimeters), pseudopolyps (as in ulcerative colitis), and skip areas (lack of continuity of involvement).330 He adds another observation, the presence of amyloidosis in the biopsy specimen. An endoscopic index for determining the severity of colonic Crohn’s disease has also been proposed.344 Figure 30-3 illustrates the characteristic longitudinal ulcerations seen in Crohn’s disease.

Unfortunately, there are frequent difficulties in the interpretation of the biopsies obtained by means of proctosigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. In a prospective study that Geboes and Vantrappen performed over an 18-month period, 71 colonoscopies were undertaken on 59 patients with Crohn’s disease.172 In comparison with barium enema examination, the segmental nature of the involvement was more apparent by means of colonoscopy. Microulceration was also more evident than by radiologic means. Radiographs yielded more information about the haustra, especially in the right colon. Colonoscopy permitted a histologic diagnosis in 24% of patients, but granulomas were found in only 19 of 321 specimens (6%). In more than one-fourth, the entire colon could not be examined, and no complications occurred. Hogan and colleagues observed that inconsistencies are often noted between macroscopic observations by the endoscopist and histologic interpretation of the biopsy specimen by the pathologist.242 They felt that the reason for this problem is the overlapping of the histologic features of the two conditions, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Changes in patients with ulcerative colitis are truly nonspecific, unless atypia or frank carcinoma supervenes. The most useful lesion found on colonoscopic mucosal biopsy of patients with Crohn’s disease is a granuloma. The limiting factor in establishing the correct diagnosis by means of biopsy, however, is the small size of the specimen. Hence, the physician or surgeon, having the benefit of clinical evaluation and the history, is often in the better position to make the correct diagnosis.

Distribution

The primary locations of the disease have been categorized by Bernell and coworkers as follows38:

Orojejunal (oral to the ligament of Treitz)

Small bowel (excluding terminal 30 cm of ileum)

Ileocecal (distal 30 cm of ileum with or without cecal involvement)

Continuous ileocolic (continuous ileocolic involvement)

Discontinuous ileocolic (both small and large bowel involvement, but without continuous inflammation in the ileocecal region)

Colorectal (confined to the colon or rectum or both only)

Radiographic Features

As previously mentioned, Crohn’s disease can occur anywhere in the alimentary tract. The disease tends to be segmental and asymmetric. Radiologic findings include skip lesions, contour defects, longitudinal ulcers, transverse fissures, eccentric involvement, pseudodiverticula, narrowing or stricture formation, pseudopolypoid changes that may be cobblestone-like, sinus tracts, and fistulas.341

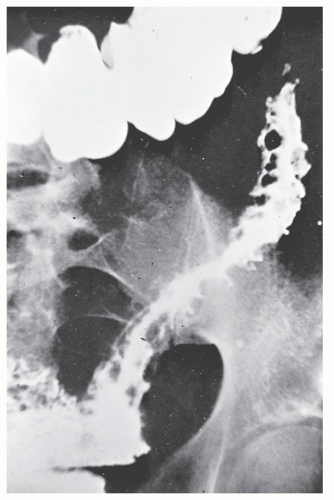

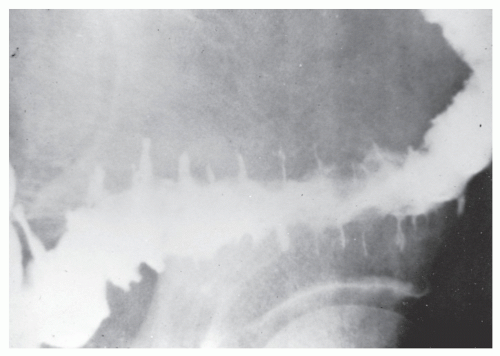

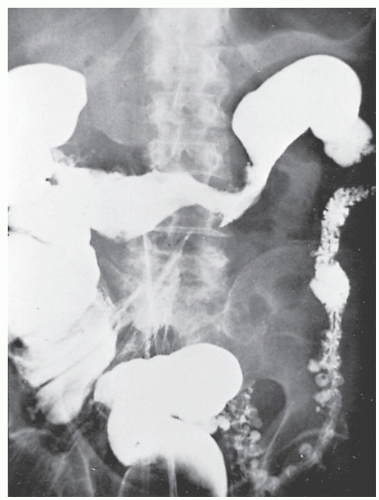

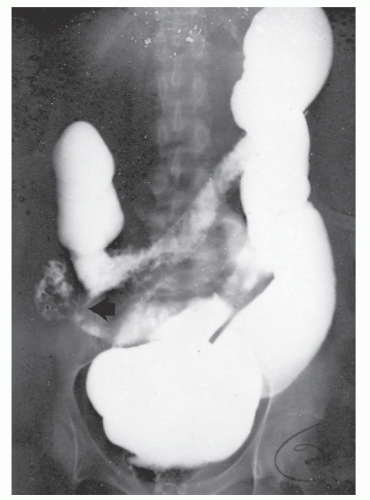

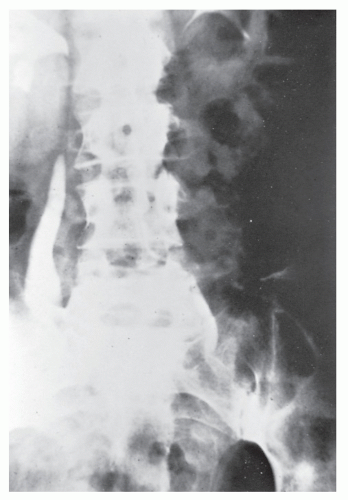

A plain film of the abdomen may be quite useful in the early stages of Crohn’s colitis. Although toxic megacolon is much less common in Crohn’s disease than it is in ulcerative colitis, acute toxic dilatation may occur before any firm cicatrix has formed in the bowel wall (Figure 30-4).

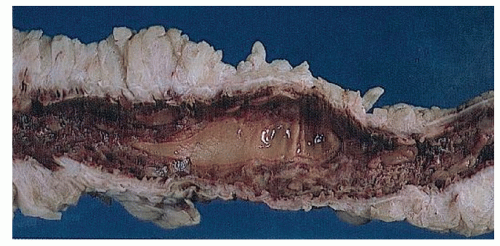

Colon

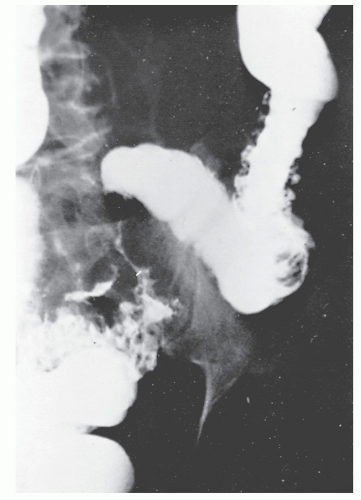

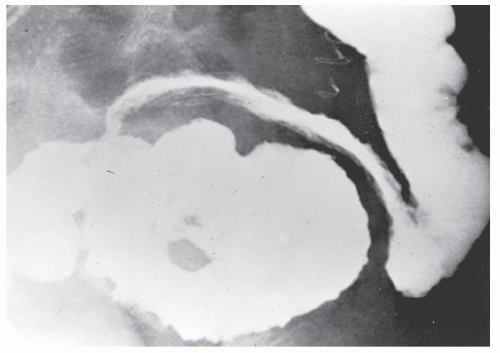

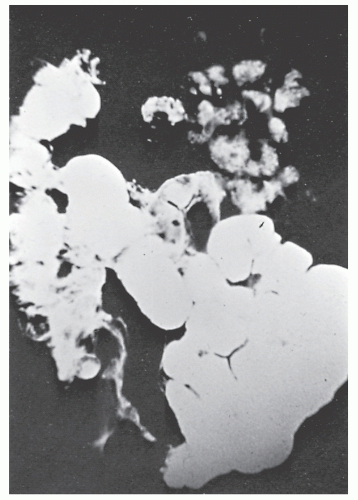

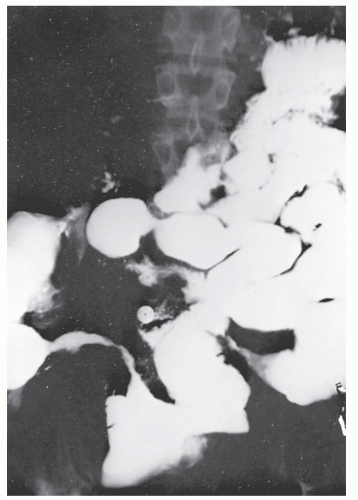

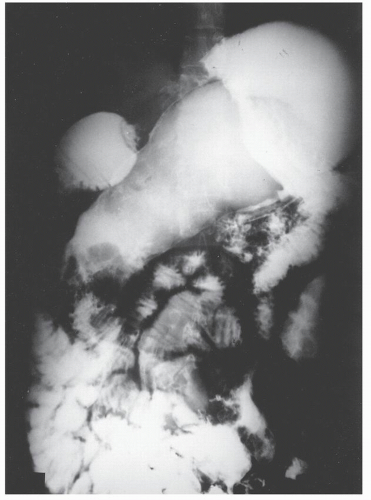

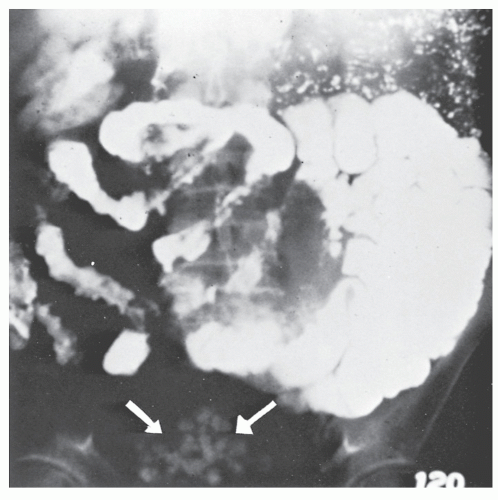

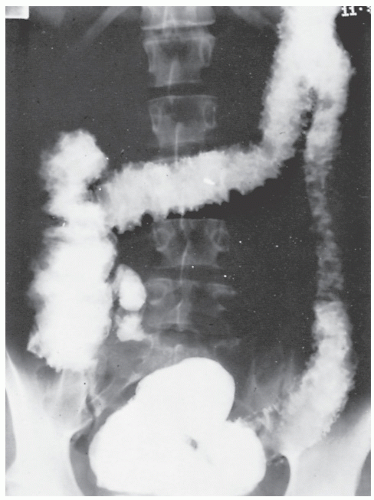

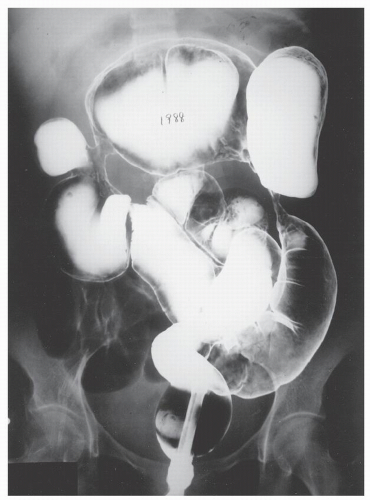

The postevacuation film is most useful in identifying numerous discrete ulcers (Figure 30-5). Small ulcerations may combine to produce large, longitudinal ulcers (Figure 30-6), and when the longitudinal ulcers combine with transverse fissures, they produce the cobblestone appearance seen radiologically (Figure 30-7). Intramural fistulas can result from the coalescing of the numerous longitudinal ulcers, which in turn may produce a doublelumen appearance (Figure 30-8). Ulcerations may penetrate beyond the contour of the bowel and present as numerous long spicules or as sinus tracts (Figure 30-9). These deep fissures may be confused with diverticula, but with experience the physician should be readily able to differentiate them. If one examines the whole-mount specimen shown in Figure 30-42, one can appreciate how such a radiologic picture can evolve.

Although the standard barium enema examination has been routinely employed in the past for evaluating IBD, contemporary evidence suggests that the air-contrast technique is preferred. Radiologists have prided themselves on their ability to identify somewhat unusual radiographic features of IBD. These include mucosal bridging and aphthoid ulcers.44,216,477,513 Although these findings are helpful in the evaluation of patients with IBD, their ready documentation by means of colonoscopy would diminish the value of the radiologic observation.

Superficial mucosal abnormalities are not uncommonly seen in the distal part of the ileum, and concern is often

expressed as to the likelihood of such a patient developing clinically recognizable Crohn’s disease. Ekberg and colleagues identified mucosal abnormalities in the distal ileum of 21 patients by means of air-contrast enemas.131 From 4 to 7 years later, neither Crohn’s disease nor any other progressive condition of the small bowel developed.

expressed as to the likelihood of such a patient developing clinically recognizable Crohn’s disease. Ekberg and colleagues identified mucosal abnormalities in the distal ileum of 21 patients by means of air-contrast enemas.131 From 4 to 7 years later, neither Crohn’s disease nor any other progressive condition of the small bowel developed.

Figure 30-10 demonstrates a number of the classical changes that one may see in the radiographic appearance of Crohn’s colitis. These include segmental distribution with sparing of the rectum, stenosis, thickening of the bowel wall, ulceration, and a suggestion of a double-lumen appearance.

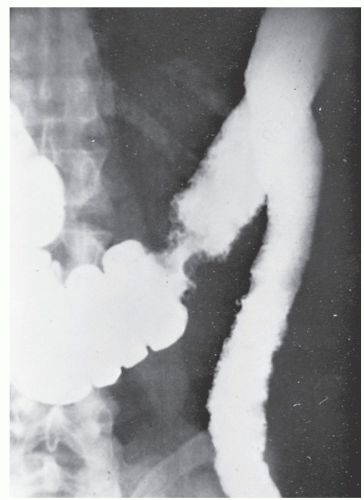

Strictures are of variable lengths and may be quite extensive indeed (Figures 30-11 and 30-12). When a stricture occurs in Crohn’s disease, it does not imply a malignant association, such as when it is seen in a patient with ulcerative colitis. However, individuals with Crohn’s disease have been shown to have an increased risk for the development of malignancy (see Relationship to Carcinoma). Differential diagnosis between a Crohn’s stricture and that of a carcinoma is usually not difficult. Close inspection often reveals that the bowel in adjacent areas is ulcerated (Figure 30-13). Contrast this x-ray with that of Figure 30-14. Although a scirrhous carcinoma must always be considered in the differential diagnosis, the lack of associated ulceration or inflammatory changes elsewhere in the colon usually clarifies the dilemma. Still, one must be wary of the possibility (see Figure 30-12).

A most difficult problem is to differentiate radiographically Crohn’s disease from tuberculosis (see Chapter 33). When the condition is confined to the ileocecal region, it is virtually impossible to distinguish between the two diseases.

Barium enema has been used to evaluate the anal canal in patients with Crohn’s disease.120 Although direct visual examination is more accurate, there are characteristic changes that may be identified by means of careful radiologic examination of the area. The hallmark of a radiologically normal anal canal is the presence of straight, smooth lines of barium between the folds, whereas an abnormal anal canal may show distortion of the folds, ulcers, fissures, sinus tracts, and fistulas.120 However, if one requires the assistance of a radiologist to make the diagnosis of anal Crohn’s disease, that physician must be considered diagnostically destitute.

Small Bowel

Upper gastrointestinal and small bowel x-ray films are quite helpful for evaluating IBD in this area of the alimentary tract, especially because there is no truly adequate nonoperative endoscopic examination of the small intestine, except for the very distal ileum, putting aside capsule endoscopy. Radiologically, evaluation of the terminal ileum is best obtained by reflux on barium enema examination, but unfortunately, as many as 20% of patients will not demonstrate this phenomenon. Alternatively, a small bowel follow-through study or an enteroclysis with good spot films can be used.

FIGURE 30-12. Air-contrast barium enema reveals multiple strictures in the colon in an individual with Crohn’s disease. At the time of surgery, these all proved to be benign. |

Increasingly, CT enterography has become utilized for demonstrating luminal disease, extent of involvement, points of obstruction, and extraintestinal complications. This study will also show the degree of mural thickening, the presence of fistula, as well as sepsis/abscess. It may show the site of target organ involvement, such as duodenum, sigmoid, and ileocolic fistula. This serves as a guide to the endoscopist as well. In the case of ileosigmoid fistula, this may be confirmed endoscopically by the appearance of a granulomatous nodule, wherein the sigmoid and rectum are otherwise normal. This may, in the case of a rare entity, ileorectal fistula, have a bearing on the surgical strategy—such as the need for mobilization of the rectum when segmental rectal resection may be required. Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum has a characteristic appearance. Thickening of the bowel wall narrows the lumen, resulting in a degree of obstruction in some patients. This is the most frequent cause of abdominal pain in individuals with Crohn’s disease. The radiologic appearance of the terminal ileum has been described as having a “string sign” (Figure 30-15). Involvement of the terminal ileum may be seen as an isolated finding or may be associated with multiple diseased areas throughout the small intestine (Figure 30-16). In contrast to radiologic evaluation of the colon for Crohn’s disease, it is virtually impossible to differentiate a benign from a malignant stricture in the small intestine (Figure 30-17). As with carcinoma of the small bowel in an individual without Crohn’s disease, the prognosis is extremely poor.

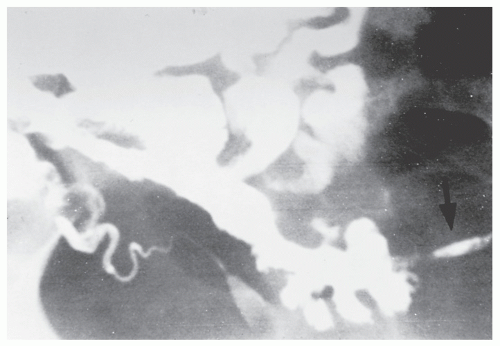

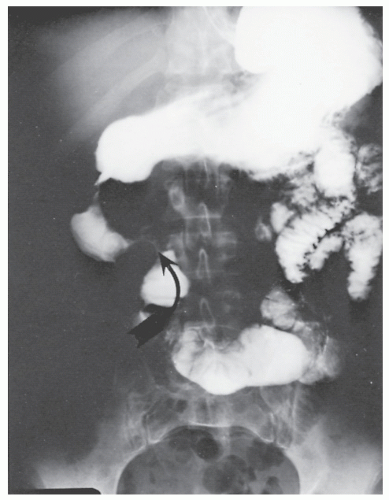

Fistulous complications are frequently seen in patients with Crohn’s disease. Communication between the ileum and colon is not uncommon (Figure 30-18), but other types of fistulas have been observed, including coloduodenal (Figures 30-19 and 30-20), and those to pelvic organs (Figure 30-21).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound examination is of quite limited value in patients with IBD because of the presence of considerable artifact associated with the loops of bowel. The presence of air or fluid in the intestine and adhesed loops may simulate a septic focus. That stated, Sonnenberg and colleagues performed a prospective clinical trial comparing 51 patients with Crohn’s disease with 124 controlled subjects by means of grayscale ultrasound.528 Diagnosis by ultrasound reflected primarily the thickening of the gastrointestinal wall itself, perceived as a characteristic “target” appearance. The study demonstrated that there were very few false negatives. The occasional false-positive phenomenon was usually attributed to the presence of a gastrointestinal tumor.

van Outryve and coworkers studied transrectal ultrasound in individuals with Crohn’s disease and in control subjects.571 The authors observed that the procedure sharply delineates the rectal wall and may detect unsuspected abscesses and fistulas in the pararectal and paraanal tissues (see Chapters 5 and 7). Abdominal ultrasound may also allow for accurate measurement of mural thickness. In the case of multiple small bowel strictures, this may impact on surgical decision making. For example, one is more likely to favor resection of a stricture if the wall thickness is 9 mm or more. Strictureplasty, if performed under this circumstance, leads to early recurrence (see later).

Computed Tomography

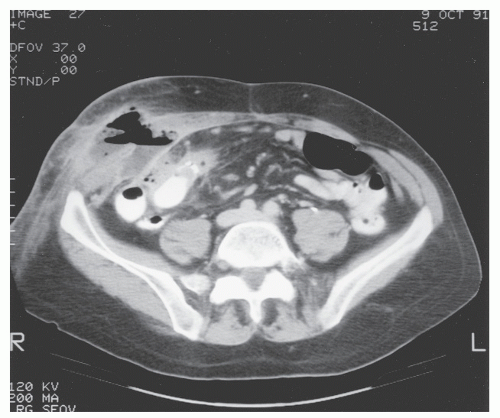

Computed tomography (CT) is able to demonstrate thickening of the colon, nodularity, adenopathy, and intra-abdominal abscess (Figure 30-22). The presence of any fistula, especially an enterocutaneous communication, is often demonstrable by means of CT scan with oral or rectal contrast. In most cases, however, adequate evaluation of intra-abdominal pathology can be obtained by means of endoscopic examination and by standard contrast techniques.

Yousem and colleagues studied CT scans of 200 consecutive patients with Crohn’s disease in order to determine the frequency and patterns of perirectal and perianal involvement.609 They observed inflammation of fat planes (73%), bowel wall thickening (30%), fistulas or sinus tracts (22%), and abscesses (14%). Because more than one-third had abnormal CT manifestations below the symphysis pubis, the authors emphasize the importance of scanning sequences to the perineum in individuals with Crohn’s disease.

Gore and colleagues attempted to provide the perspective of CT criteria in the evaluation of ulcerative, granulomatous and indeterminate colitis.191 Unfortunately, features were often overlapping, and CT did not alter the original diagnosis in any patient.

Capsule Endoscopy

The application of capsule endoscopy for evaluating the small bowel has been discussed in Chapter 5. Several studies have been published that attest to its value in assessing the small bowel in individuals with Crohn’s disease.132,162,236 However, although it may be useful for identifying an occult source of bleeding, the reality is that the overwhelming majority of patients can have their disease identified by simpler, less expensive means. Furthermore, there is a real risk of precipitating a small bowel obstruction if the capsule cannot pass a strictured area. Still, in a limited number of individuals, capsule endoscopy may be a useful diagnostic tool for this condition.

Angiography

Another method for identifying the site of small bowel bleeding in an individual with Crohn’s disease has been described, that of the combined use of preoperative angiography and highly selective methylene blue injection.441 It was felt that this technique may aid the surgeon in the preoperative and intraoperative localization of occult bleeding sites in this condition.

The Significance of Special Laboratory Studies

A number of specialized laboratory studies have been advised, primarily for evaluation of Crohn’s disease. Some have suggested the use of an indium-labeled leukocyte scan to distinguish patients for whom medical therapy may be preferable from those who may be optimally treated by surgery.518 For example, in active Crohn’s disease, labeled leukocytes are excreted into the bowel lumen from the inflamed mucosa. Patients with positive scans, therefore, have higher values of indices of disease activity. In a study by Slaton and colleagues, a negative indium leukocyte scan suggested a fibrotic ileal stricture and the advisability of surgical intervention.518 As an anatomic indicator of acute granulocytic infiltration of the intestinal mucosa and submucosa, Nelson and colleagues found that this scan had a 97% rate of sensitivity and a 100% specificity.376 The study may be best applied in individuals with fulminant disease, especially those who cannot safely be put through the rigors of endoscopy or barium contrast radiologic evaluation.

Brignola and colleagues studied various laboratory indices to determine whether any had predictive value for recurrence of Crohn’s disease.58 There was a significant correlation with recurrence and alteration of acid

1-glycoprotein, 2-globulin, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in comparison with the patients who remained in remission. Also, it has been demonstrated that patients with Crohn’s disease requiring operative treatment often have a severe peripheral lymphopenia.233 Mahida and colleagues have been able to detect interleukin-6 in seven out of eight peripheral and mesenteric samples from patients with Crohn’s disease.331 Heimann and Aufses showed that individuals who developed recurrences had significantly lower preoperative lymphocyte counts than those who were free of disease 3 years following resection.232 As more information becomes available, it is possible that these and other studies will help the physician and surgeon determine which patients are at increased risk and perhaps influence the timing and the type of therapy.

1-glycoprotein, 2-globulin, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in comparison with the patients who remained in remission. Also, it has been demonstrated that patients with Crohn’s disease requiring operative treatment often have a severe peripheral lymphopenia.233 Mahida and colleagues have been able to detect interleukin-6 in seven out of eight peripheral and mesenteric samples from patients with Crohn’s disease.331 Heimann and Aufses showed that individuals who developed recurrences had significantly lower preoperative lymphocyte counts than those who were free of disease 3 years following resection.232 As more information becomes available, it is possible that these and other studies will help the physician and surgeon determine which patients are at increased risk and perhaps influence the timing and the type of therapy.

Pathology

Macroscopic Appearance

Crohn’s disease may have protean clinical and pathologic manifestations. The condition can be confined to the colon alone or may involve only the anal canal. Fistulas, segmental involvement, rectal sparing, perianal disease, and abscess formation are all characteristic of granulomatous colitis. Some of the earliest changes in the serosal aspect of the small intestine involved by Crohn’s disease may be immediately recognizable if the patient is submitted to surgery. The intraoperative recognition of Crohn’s disease can also be inferred by the corkscrew appearance of vessels on the serosal aspect. This implies that this segment has been subjected to intermittent obstruction. The serosal vessels elongate as the bowel distends proximal to a stricture, and

when the intermittent dilatation contracts, these stretched vessels assume a corkscrew appearance. Other points suggesting involved small bowel are mesenteric marginal thickening, which corresponds to the longitudinal ulcers of Crohn’s disease in the small bowel.

when the intermittent dilatation contracts, these stretched vessels assume a corkscrew appearance. Other points suggesting involved small bowel are mesenteric marginal thickening, which corresponds to the longitudinal ulcers of Crohn’s disease in the small bowel.

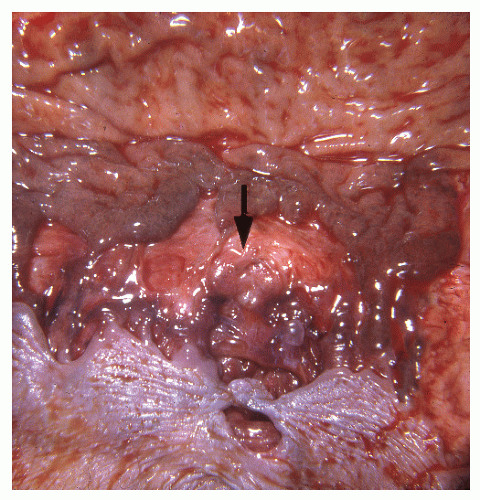

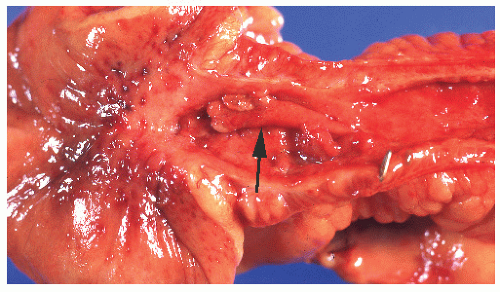

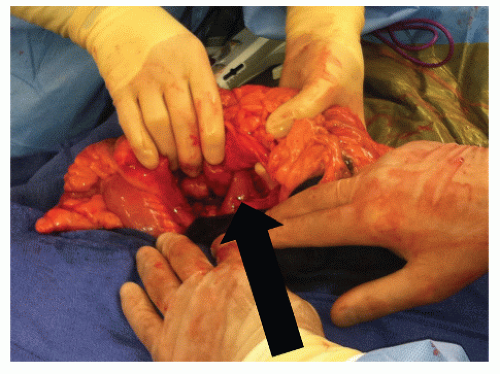

FIGURE 30-20. Coloduodenal fistula. At operation, fistula between the two structures is clearly demonstrated (arrow). |

Subserosal extension of fat around the surface of the bowel (“fat wrapping”) and a prominent vascular pattern in the serosa are characteristic of the disease (Figure 30-23). The serosal surface may be granular and bleed easily on any intraoperative abrasion. It has been demonstrated that fat wrapping correlates best with transmural inflammation and represents part of the connective tissue changes that accompany intestinal Crohn’s disease.504

FIGURE 30-22. Computed tomography demonstrates abdominal wall abscess on the right side. This was secondary to a perforating ileocolic Crohn’s inflammation. |

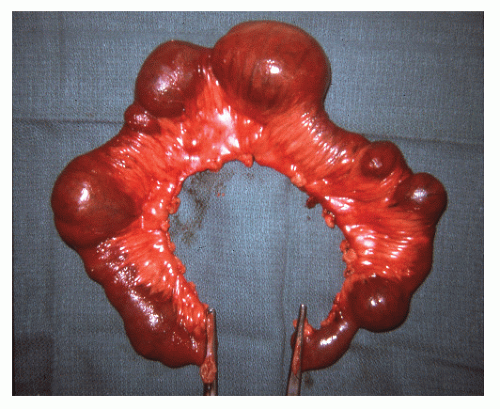

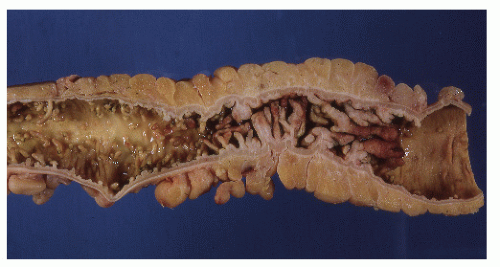

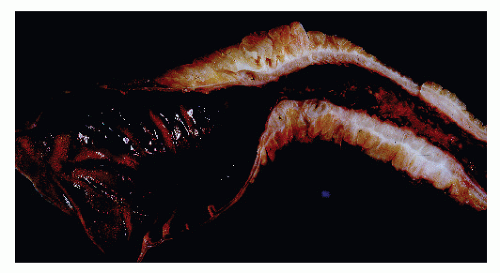

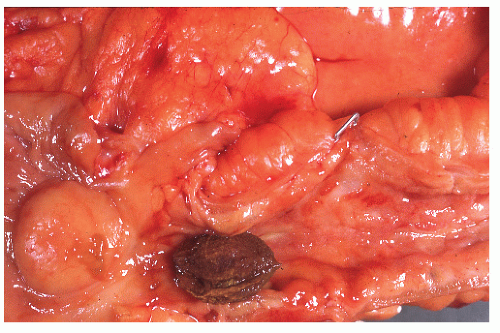

The disease frequently affects the bowel in a segmental fashion. This may produce extensive skip areas (Figures 30-24 and 30-25), limited involvement to an area of the bowel (Figure 30-26), or even a focal, isolated stricture (Figure 30-27).

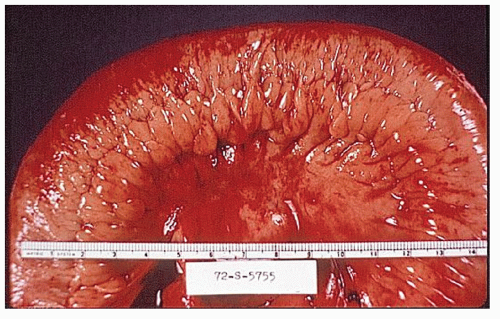

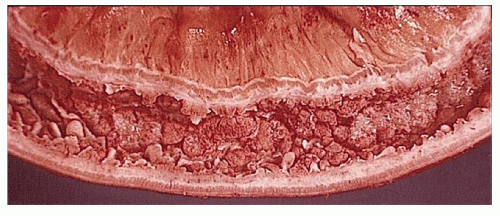

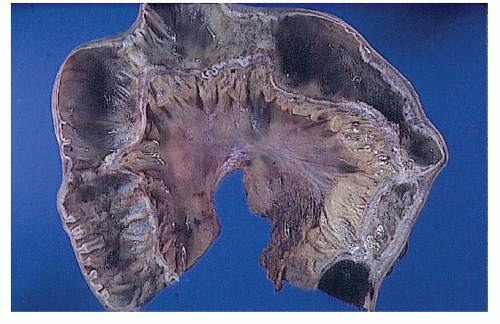

Classically, Crohn’s colitis involves the intestine in an asymmetric fashion. Areas of the bowel may demonstrate disease on the mucosal aspect with sparing of adjacent sites, leaving islands of somewhat edematous but otherwise nonulcerated mucosa (Figures 30-28,30-29 and 30-30). Ulceration in an irregular fashion with large areas of uninvolved mucosa interspersed between broad, twisting lesions is quite characteristic. The relative sparing between ulcers is not seen in ulcerative colitis. Another characteristic feature of the macroscopic appearance of Crohn’s disease is the thickening of the bowel wall. Involvement through all the layers, along with the cobblestone appearance of the mucosa, has been described as “stones in a running brook” (Figure 30-31).

FIGURE 30-25. Crohn’s disease. This opened specimen from Figure 30-24 reveals the segmental nature of the disease. Thickening of the mesentery is a prominent feature. (From Corman ML, Veidenheimer MC, Nugent FW, et al. Diseases of the Anus, Rectum and Colon. Part II: Non-specific Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New York, NY: Medcom; 1976.) |

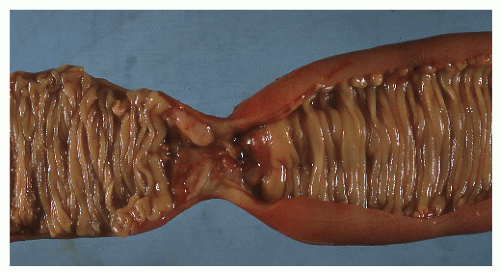

Crohn’s colitis frequently involves the colon and ileum in continuity. Conversely, cecal ulceration can be seen with primarily ileal disease (Figure 30-32). Occasionally, the ileal disease may terminate abruptly at the ileocecal valve, sparing the large bowel (Figure 30-33). Thickening of the bowel wall may produce sufficient narrowing to precipitate intestinal obstruction or to impede the passage of swallowed seeds or nuts (Figure 30-34). Gallstone ileus has even been reported to produce obstruction at a point of stenosis caused by Crohn’s disease.499

A common manifestation of Crohn’s disease is fistula formation. Fistulas may occur into any adjacent organ, such as the small or large bowel, bladder, vagina, uterus, ureter, or skin. Burrowing of the fissures deep into the bowel wall predisposes to fistula formation. Fistulas occur more commonly in the mesocolic aspect of the bowel than on the antimesocolic border (Figure 30-35).

Although nodal adenopathy is frequently present, the location of enlarged, paraileal lymph nodes is a reasonably accurate way of identifying the proximal extent of disease without the need of verifying this by entering the bowel.

Occasionally, diffuse mucosal disease may produce a pseudopolypoid pattern similar to that of chronic ulcerative colitis. Giant pseudopolyps may actually mimic neoplasms endoscopically and radiographically. The condition is most likely the result of fusion of numerous fingerlike pseudopolyps.207 A number of reports and reviews of this manifestation have been published.113,207,263

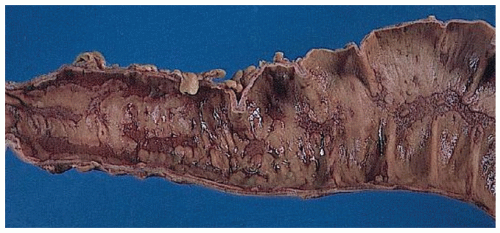

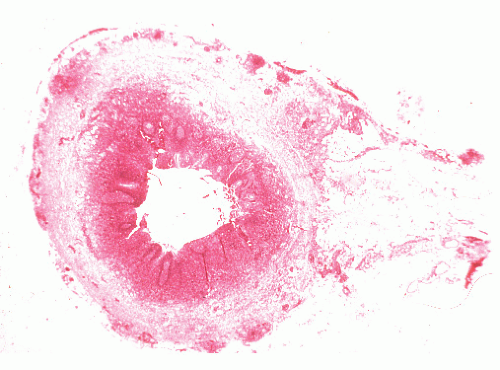

Histologic Appearance

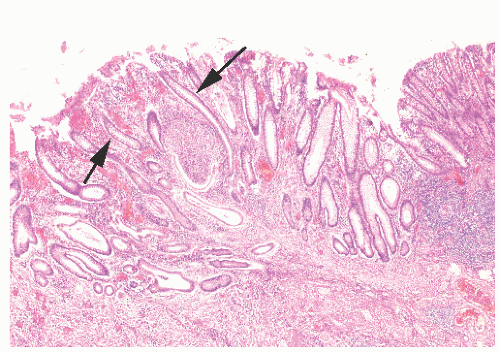

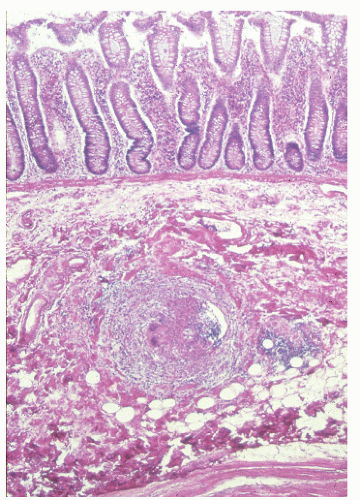

The three primary histopathologic findings in patients with Crohn’s colitis are transmural inflammation and fibrosis, granulomas, and narrow, deeply penetrating ulcers or “fissures” (Figure 30-36). The mucosal inflammation of Crohn’s disease differs from that of ulcerative colitis in that typically there are fewer crypt abscesses, there is less congestion, and there is better preservation of the goblet cell population (Figure 30-37).

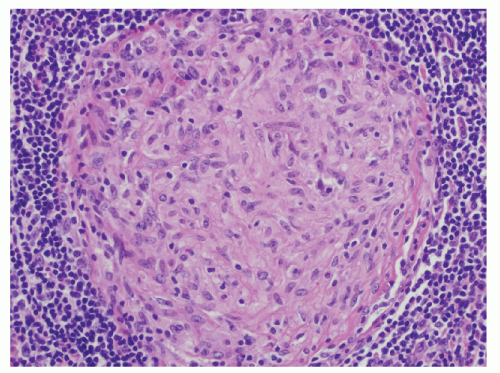

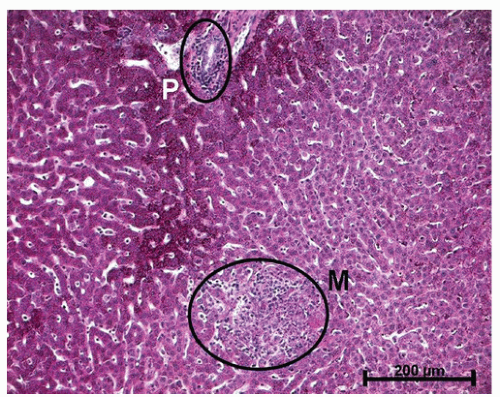

Granulomas may occur in any part of the bowel wall and are usually identified in approximately two-thirds of all patients with Crohn’s colitis. If a biopsy is performed in an attempt to differentiate between the two inflammatory conditions, the material should be obtained from a noninflamed area if possible (Figure 30-38). A granuloma, albeit a foreign body type, may actually be seen even with ulcerative colitis in an area of acute inflammation. Multiple biopsy specimens are suggested because submucosal lesions tend to be very small (microgranulomas).289 The microscopic appearance of

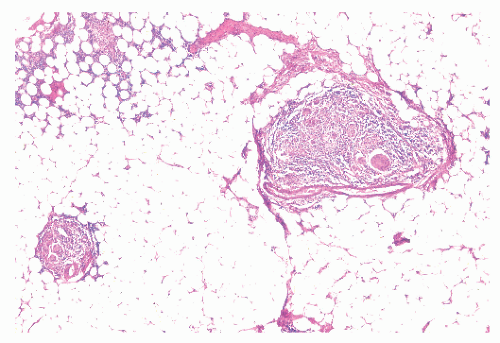

the granuloma is not diagnostic, and the possibility of an infectious agent should always be considered (Figure 30-39). Granulomas can also occur in the liver (Figure 30-40) and in the omentum (Figure 30-41) as well as in other sites.

the granuloma is not diagnostic, and the possibility of an infectious agent should always be considered (Figure 30-39). Granulomas can also occur in the liver (Figure 30-40) and in the omentum (Figure 30-41) as well as in other sites.

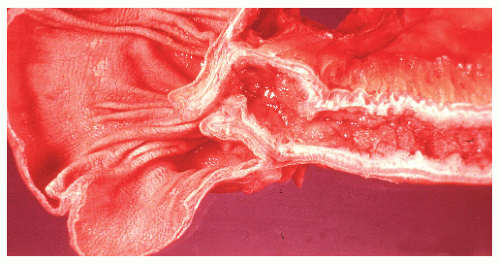

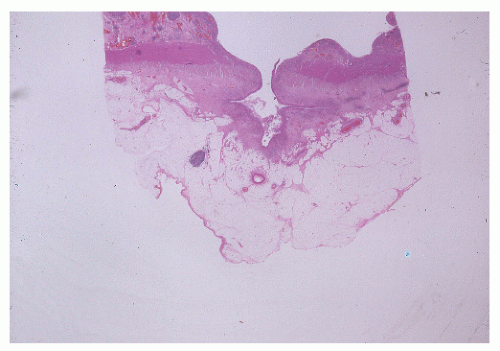

Narrow, deeply penetrating ulcers or fissures are the third characteristic feature of Crohn’s disease. The fissures may penetrate through the inner circular layer of the muscularis and are visible on the radiographs after a barium enema as spicules. A sinus tract present in the fat adjacent to the bowel wall indicates that one of the fissures has penetrated through the wall (Figure 30-42). When this occurs, a sinus may burrow into another organ to produce a fistula.

Information about the pathology of IBD has been further gleaned by means of electron microscopy. Early epithelial changes can be identified using this modality in areas that appear to be uninvolved. These include necrosis of individual columnar epithelial cells; budding of the tips of microvilli; thickening, shortening, irregularity, and fusion of intestinal villi; numerous Paneth’s cells; hyperplasia of goblet cells; and augmented mucous secretion.271 Other studies such as tissue-enzyme analysis, jejunal-surface pH, and differences in sodium flux and mucosal potential imply that the disease often is far more extensive than is recognized by other, more conventional means, and certainly much more extensive than is usually apparent at the time of surgery.

Another observation is the increased secretion of mucus by the bowel in Crohn’s disease as compared with decreased colonic mucus in ulcerative colitis. The decrease may be explained by destruction of the epithelial cells.271 A number of biochemical changes have also been observed.

Extraintestinal Manifestations

For convenience and in order to avoid duplication, I have elected to place the discussion of extraintestinal manifestations in this chapter. Moreover, because so many of the

manifestations in other areas of the body are exclusively seen in Crohn’s disease, the discussion is placed here, although many such problems may be seen in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Increasing evidence supports the statement that inflammatory disease of the intestine is a systemic problem rather than one localized to the small or large bowel. In a population-based study from Sweden of 1,274 patients with ulcerative colitis, the overall prevalence of extracolonic diagnoses was 21%.363 As discussed in Chapter 29, many etiologic concepts have been considered, but regardless of the sequence of pathologic changes in the colon, there is little question about the presence of related events, at times profound, in distant areas of the body. The joints, skin, liver, kidneys, eyes, mouth, blood, nervous system, and, of course, other areas of the alimentary tract may be sites of lesions that, at least in the extraintestinal manifestations, often seem dependent on the presence of diseased bowel. So broad indeed is the spectrum of Crohn’s disease that specialists in dentistry, otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology, and dermatology must be prepared to recognize its manifestations.

manifestations in other areas of the body are exclusively seen in Crohn’s disease, the discussion is placed here, although many such problems may be seen in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Increasing evidence supports the statement that inflammatory disease of the intestine is a systemic problem rather than one localized to the small or large bowel. In a population-based study from Sweden of 1,274 patients with ulcerative colitis, the overall prevalence of extracolonic diagnoses was 21%.363 As discussed in Chapter 29, many etiologic concepts have been considered, but regardless of the sequence of pathologic changes in the colon, there is little question about the presence of related events, at times profound, in distant areas of the body. The joints, skin, liver, kidneys, eyes, mouth, blood, nervous system, and, of course, other areas of the alimentary tract may be sites of lesions that, at least in the extraintestinal manifestations, often seem dependent on the presence of diseased bowel. So broad indeed is the spectrum of Crohn’s disease that specialists in dentistry, otorhinolaryngology, ophthalmology, and dermatology must be prepared to recognize its manifestations.

FIGURE 30-40. Crohn’s disease. Granuloma of the liver in a patient with Crohn’s colitis. (Original magnification × 260.) |

Oral Manifestations

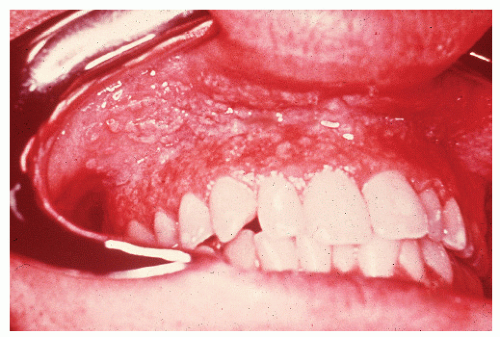

Oral lesions were first identified in Crohn’s disease by Dudeney and Todd in 1969.121 Since then, a number of papers

have been published on the subject.42,47,521,574 Inflammatory changes in the mouth may even be the initial site of involvement.87 Basu and Asquith reviewed the oral manifestations of IBD, describing a number of lesions.33 These included recurrent aphthous ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, pyostomatitis vegetans, hemorrhagic ulceration, glossitis, macroglossia, and moniliasis. The authors reported that the incidence is not as uncommon as one might expect, with up to 20% having been described as having oral lesions. The most frequently affected areas and their respective appearances are the buccal mucosa (a cobblestone pattern), the vestibule (linear, hyperplastic folds), and the lips (diffusely swollen and indurated).43

have been published on the subject.42,47,521,574 Inflammatory changes in the mouth may even be the initial site of involvement.87 Basu and Asquith reviewed the oral manifestations of IBD, describing a number of lesions.33 These included recurrent aphthous ulcers, pyoderma gangrenosum, pyostomatitis vegetans, hemorrhagic ulceration, glossitis, macroglossia, and moniliasis. The authors reported that the incidence is not as uncommon as one might expect, with up to 20% having been described as having oral lesions. The most frequently affected areas and their respective appearances are the buccal mucosa (a cobblestone pattern), the vestibule (linear, hyperplastic folds), and the lips (diffusely swollen and indurated).43

Aphthous ulcers usually parallel the course or activity of the IBD: the more active the disease, the more likely one is to develop this complication. Biopsy usually shows a chronic inflammatory reaction.

Pyostomatitis vegetans is an unusual manifestation of IBD. Papillary projections of mucous membrane can be seen separated by small areas of ulceration (Figure 30-43). Biopsy may reveal suprabasal separation of the oral epithelium and infiltration with eosinophils.

The recognition of the specific oral granuloma is important because it may be the first manifestation of Crohn’s disease.521 Scully and colleagues reported 19 patients with clinical evidence of oral Crohn’s disease but no intestinal symptoms.498 More than one-third were demonstrated either on rectal biopsy or by contrast gastrointestinal x-ray films to have IBD, even in the absence of symptoms.

Treatment

Because the lesions are resistant to local therapy, general measures for soothing the oral discomfort are advised. The symptoms and clinical findings of oral problems are often ameliorated with appropriate treatment of the intestinal disease.

Esophageal Involvement

Patients with Crohn’s disease of the esophagus will present with symptoms not unlike those associated with other lesions of that organ, such as carcinoma. Substernal discomfort, dysphagia, epigastric pain, weight loss, nausea, and vomiting are all part of the clinical spectrum. Other gastrointestinal symptoms are usually due to the presence of disease elsewhere in the alimentary tract.126,174,231 It must be remembered that dysphagia and the demonstration of an esophageal ulcer or esophagitis in a patient with known Crohn’s disease can be due to reflux esophagitis, certain drugs or corrosive agents, pressure from a nasogastric tube, infectious agents, sarcoidosis, or Behçet’s disease.380 In point of fact, many published reports of esophageal Crohn’s disease cannot be supported by critical review.

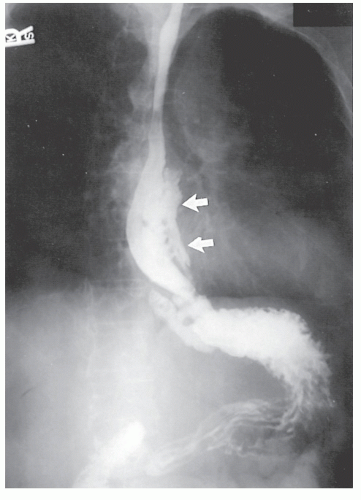

Physical examination is usually unrewarding with respect to esophageal involvement. Diagnosis is usually made by a high index of suspicion and radiologic investigation, which obviously would include a barium swallow (Figure 30-44). This study may reveal thickened mucosal folds, multiple ulcerations, or, most commonly, a stricture. This last finding makes differentiation from carcinoma quite difficult, except that the presence of disease elsewhere or the relatively young age of the patient should lead one to suspect an inflammatory process.

Endoscopic examination will usually reveal hyperemia with possibly either an ulcerated mucosa or the presence of an inflammatory stricture. Biopsies usually show an inflammatory reaction, but the absence of granulomata does not exclude the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.126

Treatment usually consists of the standard medical management appropriate for Crohn’s disease of the small or large bowel (see Chapter 29 and Medical Management). Resection is rarely indicated.

Gastroduodenal Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease involving the stomach and duodenum may not be as rare as originally suspected. Since the original description in 1937 by Gottlieb and Alpert of the condition in the duodenum, a number of cases have been reported.192 In 1981, Korelitz and colleagues performed random endoscopic biopsies of the stomach and duodenal mucosa in patients with Crohn’s disease, frequently demonstrating the presence of microscopic alterations consistent with this inflammatory process in the upper gastrointestinal tract.282 Clinically, evident IBD of the gastroduodenal area is believed to occur in approximately 2% or 3% of all patients with Crohn’s disease. The condition can occur without involvement elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract, but this is extremely uncommon.

Patients usually present with epigastric abdominal symptoms exacerbated by eating—nausea, vomiting, and weight loss. Symptoms may resemble those of ulcer disease. Obstruction, perforation, fistula, and hemorrhage can occur. A fistula into the stomach characteristically produces symptoms of feculent vomiting, eructation, and odor. Duodenocolic fistula is a recognized complication of duodenal disease, but in evaluation of patients with this finding, it is important to ascertain whether the fistula arose from inflammatory disease of the intestinal tract outside of the duodenum or from the duodenum, itself (see Figures 30-19 and 30-20). Most observers agree that gastroenteric and duodenoenteric fistulas are almost always due to intestinal disease.

Radiologic investigation may reveal the findings summarized by Cohen.91 These include antral inflammation, contiguous disease in the duodenum, cobblestone mucosal appearance with thickened folds, reduced distensibility or stricture, and ulceration (Figure 30-45). Barium enema examination is the preferred study for identifying a fistula between the upper gastrointestinal tract and the colon.

Endoscopic examination may reveal ulceration, cobblestoning, or stricture. As with esophageal disease, the absence of granulomata does not necessarily mean that the patient does not have Crohn’s. Nugent and Roy found granulomas in 37 of 76 individuals (49%).385

Treatment usually consists of antacids and proton pump inhibitors or H2 receptor blockers (an antiulcer program), the medical regimens discussed later, hyperalimentation, and possibly surgical intervention. The primary indications for operation are the presence of a fistula and obstruction (see later). If hemorrhage cannot be controlled by medical means, either resectional surgery or oversewing the bleeding

point is the treatment of choice. Usually, however, surgery for primary gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease can be avoided.

point is the treatment of choice. Usually, however, surgery for primary gastroduodenal Crohn’s disease can be avoided.

Management of Duodenal Stricture

The most commonly performed operative procedure for duodenal Crohn’s disease is gastrojejunostomy, but complications such as bile reflux gastritis, stomal ulceration, blind loop syndrome, and the potential need for a vagotomy are real concerns. Strictureplasty has also been applied for duodenal disease, but in the findings of the Birmingham, England, group, it is associated with a high incidence of postoperative complications, the need for reoperative surgery, and the likelihood of restricture.601 However, our group undertook duodenal strictureplasty on 13 patients and found that it is a safe and effective operation that should be considered when technically feasible.596

A number of cases and reviews have been published on the evaluation and management of the condition as it affects this area.93,100,140,164,255,470,592 Nugent and colleagues reported 18 patients from the Lahey Clinic who were relieved of obstruction by means of gastrojejunostomy.384 This was their preferred treatment for those with this complication. The authors did not advise vagotomy because of the risk of diarrhea and the fact that there was no difference in results between the vagotomized and nonvagotomized groups. A later report from the same institution involved 25 patients who required operation.371 That study revealed that one-third who underwent bypass required reoperation, usually for marginal ulceration or for gastroduodenal obstruction. Although the authors did not feel that the addition of vagotomy protected against the subsequent development of marginal ulceration, they recommend in their latest report that a vagotomy be performed. Shepherd and Alexander-Williams have lent additional support to the concept of vagus nerve interruption when they reported a patient who developed a stomal ulcer 8 weeks following gastroenterostomy without vagotomy.505

Management of Gastric and Duodenal Fistulas

When a fistula develops as a consequence of intestinal disease, simple closure of the stomach or duodenum is all that is usually required, along with resection of the involved bowel segment. Gastric fistulas are always due to disease in the intestine. Treatment of the gastric opening is wedge excision. Occasionally, the opening in the duodenum may occur in an area that is difficult to close, such as adjacent to the pancreas. In this situation and when a large defect is created, an omental or jejunal patch, or the creation of a duodenojejunostomy may be necessary. Lee and Schraut reported one death due to a duodenal leakage in 11 patients with fistulas.300 Greenstein and colleagues noted only nine instances of gastric fistula in a review of 1,480 individuals with Crohn’s disease.200

Results

Ross and associates reviewed the long-term results of surgery for duodenal Crohn’s disease that had been initially reported by Farmer and colleagues at our institution.140,457 Of the 11 patients, 7 required a total of 10 further operations; the mean follow-up was approximately 14 years. Indications for subsequent surgery included marginal ulceration, recurrence producing obstruction at the enteroenterostomy, and duodenal fistula. Eight of the 11 also required surgery for Crohn’s disease elsewhere in the intestinal tract. The authors concluded that bypass surgery alone was unsatisfactory in the long term and suggested that vagotomy be added at the time of operation. Functional results were felt to be better, particularly if reoperative surgery were done in an expeditious and timely manner.

The Lahey Clinic experience now comprises 89 patients.385 Their investigators conclude that irrespective of medical or surgical treatment, duodenal Crohn’s disease follows a more benign course than when it affects the small bowel or colon.

Pancreatic Manifestations

Pancreatitis or pancreatic insufficiency has occasionally been reported with IBD, but this had been felt to be coincidental. One must be aware, however, of the risk of pancreatitis that may be associated with the administration of mercaptopurine (Purinethol). Seyrig and colleagues identified six patients who were thought to have a nonfortuitous association.500 They noted the following, possibly important, clinical distinctions:

Abdominal pain was absent or moderate and probably due to bowel involvement.

Pancreatic calcifications were absent.

Those patients with pancreatic insufficiency had essentially normal pancreatograms.

More information will be necessary before one can establish with certainty whether pancreatic disease is truly an extraintestinal manifestation of IBD.

Hepatobiliary Disease

Liver function studies and liver biopsy often demonstrate abnormal results in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients. Cohen and associates performed a prospective study of liver function in 50 consecutive patients with regional enteritis.90 Thirty percent had abnormal results, most commonly an elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase, but none had significant liver disease. Fifteen patients of the 19 who underwent liver biopsy had evidence of chronic pericholangitis. Others reported an even higher associated incidence of liver abnormalities.103,118 The reasons for the association between hepatobiliary disease and IBD are not known, but a number of studies have postulated that recurrent cholangitis is due to a portal bacteremia from the interrupted intestinal mucosa, in addition to a probable genetic predisposition.83 Hepatoportal venous gas has been seen in patients with known Crohn’s disease.12

Gallbladder

Cholelithiasis has been reported in up to one-third of patients with IBD, especially in those with Crohn’s ileitis.90 The explanation for this association is believed to involve the enterohepatic circulation. Disease or resection of the terminal ileum leads to loss or malabsorption of bile acids. Because the solubility of cholesterol depends on bile acids, excessive loss may precipitate this substance. This, in turn, may result in stone formation. Another explanation may be the colonization of the terminal ileum by anaerobic bacteria that deconjugate the bile acids to less well-absorbed substances. It is not clear, however, that there is a higher incidence of gallstones in patients with Crohn’s disease than in individuals with ulcerative colitis. Lorusso and colleagues demonstrated an increased risk of gallstones in both conditions, but it was highest in those with Crohn’s disease involving the distal ileum.326 Because of the high prevalence of cholelithiasis in the population, gallbladder imaging has been recommended preoperatively and in the follow-up of IBD patients.290

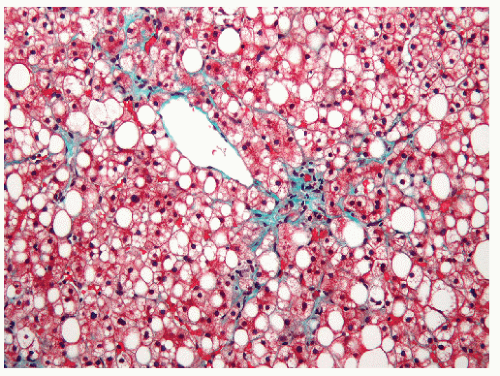

FIGURE 30-46. Fatty degeneration of the liver. Note the fat globules in the liver parenchyma. (Original magnification × 260, Trichrome stain.) |

A different perspective was expressed by Chew and colleagues.82 They retrospectively studied 134 of their patients who had undergone ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease by means of a questionnaire, using a control group matched for age and gender. There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to prevalence of cholecystectomy. However, those who had more than 30 cm of ileum removed were more likely to have undergone a cholecystectomy. The investigators concluded that synchronous prophylactic cholecystectomy with ileocolic resection cannot be justified based on their data.82

Fatty Degeneration

Fatty degeneration is probably the most frequently encountered microscopic abnormality (Figure 30-46). The incidence has been reported to be as high as 80% and to be due to the relatively poor nutritional state of many colitic patients.83 Occasionally, a granuloma may be seen (see Figure 30-47). Treatment is directed toward correction of the malnutrition.

Pericholangitis

Another common histologic manifestation of liver disease is pericholangitis (Figure 30-47). A more accurate term is portal triaditis because of involvement of bile ductules, portal venules, lymphatics, and hepatic parenchyma.83 The condition may present with jaundice, abdominal pain, fever, and pruritus. Many patients, however, are asymptomatic. Bacterial infection and an autoimmune process have been implicated as possible causative factors. There is no specific treatment for this condition.

Hepatitis

Chronic active hepatitis occurs in only 1% of patients with IBD. Conversely, the incidence of IBD in patients with chronic active hepatitis varies from 4% to 30%.83 Patients have been reported to improve following removal of diseased bowel.

Sclerosing Cholangitis

One of the most serious, albeit rare, consequences of IBD that occurs as a complication of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease is primary sclerosing cholangitis. Olsson and associates diagnosed this condition in 3.7% of indi-viduals with ulcerative colitis.391 LaRusso and colleagues reported that 70% of their patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis had IBD.295 Broomé and coworkers determined in their evaluation of 76 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis that histologic changes within the bowel itself may be observed and may actually precede development of clinical symptoms by as much as 7 years.60 The importance of identifying such individuals cannot be overestimated. It has been suggested that even the preclinical manifestations of IBD may subject that individual to an increased risk for the development of malignancy.

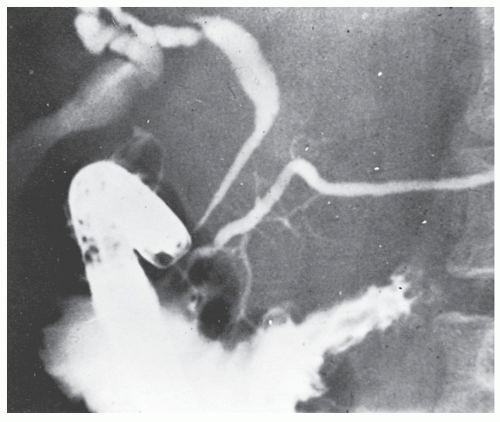

Primary sclerosing cholangitis has been much more common in patients with ulcerative colitis than in those with Crohn’s disease. The cause is unknown, but toxins, infectious agents, altered immunity, and a genetic predisposition have been suggested.295 To establish this diagnosis, there must be no prior history of biliary surgery or gallstones, no diffuse involvement of the extrahepatic biliary ducts, and the absence of subsequent development of cholangiocarcinoma.576 Symptoms include right upper quadrant abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice, and pruritus. Laboratory studies demonstrate the usual changes suggestive of an obstructive jaundice. Cholangiogram reveals a strictured bile duct (Figure 30-48). In contrast to other extraintestinal manifestations of IBD, when the sclerosing cholangitis has been established, removal of the diseased colon does not reverse the condition. The condition is a progressive disease that leads to liver damage and, eventually, liver failure. Liver transplant is the only known cure for primary sclerosing cholangitis, but transplant is typically reserved only for those with severe liver disease. Researchers continue looking into treatments to slow or reverse bile duct damage caused by primary sclerosing cholangitis. But until an effective protocol is found, treatment is directed toward reducing signs and symptoms. Medications and management include a choleretic, such as ursodeoxycholic acid, periodic MR studies of the liver, and as needed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with dilation of strictures. Endoscopic dilation of dominant strictures, with

or without stenting, has been shown to alleviate cholestasis and to improve laboratory test results. Monitoring with liver function tests is advisable.

or without stenting, has been shown to alleviate cholestasis and to improve laboratory test results. Monitoring with liver function tests is advisable.

Shaked and coworkers reported their experience with 36 patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis, using immunosuppression with cyclosporine, azathioprine (AZA), and steroids.502 Of these individuals, 29 were known to have chronic ulcerative colitis. The investigators demonstrated that liver replacement and immunosuppression in those suffering from sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis do not alter the course of the colonic disease. Bleday and colleagues have demonstrated that there appears to be a group of patients who have undergone liver transplant who rapidly develop colorectal malignancy.49 These individuals require frequent, long-term surveillance following transplant. This suggests that the immunosuppressive agents employed for managing patients who have undergone orthotopic liver transplantation may have a pejorative effect on the colon through increased predisposition for the development of malignancy. But there is no evidence to suggest an association between sclerosing cholangitis itself and colorectal carcinoma in patients with IBD.382 However, a number of cases of carcinoma of the gallbladder have been described in individuals with sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis.119

Interestingly, despite massive immunosuppression associated with transplanting small intestine, histologically confirmed recurrent Crohn’s disease has been demonstrated in the transplanted bowel.539

Cangemi and colleagues prospectively compared the progression of clinical, biochemical, cholangiographic, and hepatic histologic features in 45 patients with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis, 20 of whom underwent proctocolectomy and 25 of whom had not.72 No beneficial effect was seen as a consequence of the operation. Because of the profoundly serious consequences of progressive cholangitis, a case may be made for “prophylactic” removal of the inflammatory bowel process if early changes in the biliary tract are observed. This has been suggested even when the gastrointestinal manifestations are quite minimal, but there is no evidence to support implementation of this concept. Still, if surgical treatment is needed for the IBD itself, those with well-controlled primary sclerosing cholangitis can undergo such operations as restorative proctocolectomy safely (for ulcerative colitis).415

Cirrhosis

Although cirrhosis is an uncommon complication of IBD, it has, in the past at least, been felt to cause 10% of deaths.83 When it occurs it is usually a consequence of sclerosing cholangitis. Patients may develop the characteristic stigmata of portal hypertension, including bleeding esophageal varices, and ileostomy hemorrhage (see Chapter 31).

Carcinoma of the Bile Duct

Carcinoma of the bile duct arising in a patient with ulcerative colitis is a rare complication. The association was originally described by Parker and Kendall in 1954.402 In 1974, Ritchie and colleagues identified 67 cases.450 The condition is more common in men and is usually seen in patients who have had a prolonged history of colitis. Patients give a history of typical biliary obstruction with painless jaundice, weight loss, and pruritic symptoms. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by ultrasound demonstration of dilated intrahepatic ducts and by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Prognosis is poor, with biliary diversion the usual surgical approach.587

Cutaneous Manifestations

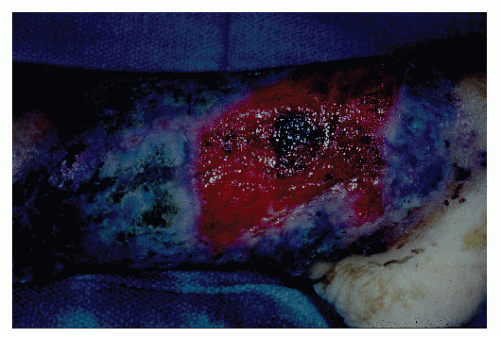

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

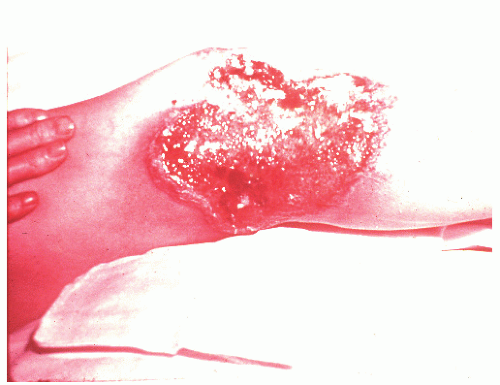

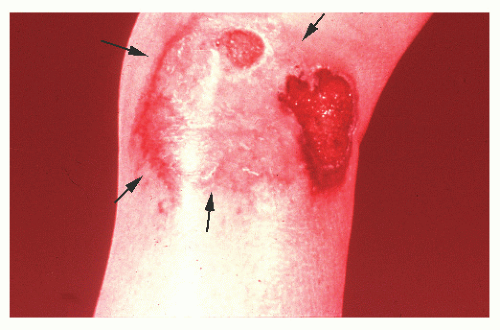

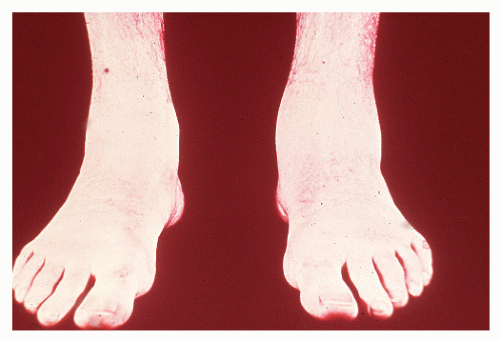

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a condition found exclusively in individuals with IBD but is fortunately uncommon,

occurring in no more than 2% of patients.362 Schoetz and associates identified 8 of 961 with Crohn’s disease (an incidence of 0.8%).495 The vast majority of patients have active intestinal disease at the time the pyoderma develops, although in rare cases the skin lesions may antedate apparent bowel involvement.362 Clinically, the lesion appears as a spreading, undermining ulceration that has a characteristic violaceous border (Figures 30-49 and 30-50). It is usually found on the extremities, the most common location being the anterior tibial area.419 However, the ulcers can occur on the trunk, buttocks, and other places. Usually, there are only one or two lesions, but these can be of considerable size.

occurring in no more than 2% of patients.362 Schoetz and associates identified 8 of 961 with Crohn’s disease (an incidence of 0.8%).495 The vast majority of patients have active intestinal disease at the time the pyoderma develops, although in rare cases the skin lesions may antedate apparent bowel involvement.362 Clinically, the lesion appears as a spreading, undermining ulceration that has a characteristic violaceous border (Figures 30-49 and 30-50). It is usually found on the extremities, the most common location being the anterior tibial area.419 However, the ulcers can occur on the trunk, buttocks, and other places. Usually, there are only one or two lesions, but these can be of considerable size.

FIGURE 30-49. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Irregularly outlined, sharply defined ulceration with edematous edges and pyodermatous base in a patient with ulcerative colitis. (Courtesy of Rudolf Garret, MD.) |

Biopsy shows no definite characteristics that would identify the ulcer as being specific for a complication associated with IBD. A vasculitis has been suggested as a possible etiology.