Chapter 30 Pasquale Casale, MD; Douglas A. Canning, MD b. Associated findings include small size with persistent fetal lobations, anterior or horizontal pelvis, anomalous vasculature, contralateral agenesis, hydronephrosis (50%), vesicoureteral reflux (30%), müllerian anomalies in 20% to 60% of females; undescended testes, hypospadias, urethral duplication in 10% to 20% of males; skeletal and cardiac anomalies in 20%. c. Adrenal gland in normal location d. Only workup, ultrasound, voiding cystourethrography (in past routine, now more selective, and only in those with urinary tract infection (UTI)) 2. Thoracic ectopia a. Comprises less than 5% of ectopic kidneys (1:13,000) b. Origin is delayed closure of diaphragmatic angle versus “overshoot” of renal ascent. c. Adrenal is usually in normal location. d. Diagnosis usually is made on plain chest radiograph. e. No treatment is needed. 3. Crossed ectopia and fusion (Bauer) (Figures 30-1 and 30-2) b. Origin is from abnormal migration of ureteral bud or rotation of caudal end of fetus at the time of bud formation. c. Associated findings include multiple or anomalous vessels arising from the ipsilateral side of the aorta and VUR; with solitary crossed kidney only; genital, skeletal, and hindgut anomalies in 20% to 50%. Risk of ureteropelvic (UPJ) obstruction (30%), VUR (15%) or cystic dysplasia also exists. d. Diagnosis is with ultrasound, renal scanning, or magnetic resonance urography (MRU). 4. Horseshoe kidney a. Incidence is 1 per 400 or 0.25%; 2:1 males. It is the most common fusion anomaly. b. Origin is fusion of lower poles before or during rotation (4½ to 6 weeks gestation) (Figure 30-3). c. Associated findings include anomalous vessels; isthmus between or behind great vessels hindered by the inferior mesenteric artery; skeletal, cardiovascular, and central nervous system (CNS) anomalies (33%); hypospadias and cryptorchidism (4%), bicornuate uterus (7%), UTI (13%); duplex ureters (10%), stones (17%); 20% of trisomy 18 and 60% of Turner patients have horseshoe kidney. d. Excluding other anomalies, survival is not affected. e. Stones; infection may result from stasis; rarely is true obstruction present (see ureteropelvic junction obstruction [UPJO]). f. Most are asymptomatic despite associated anomalies. 5. Bilateral renal agenesis b. Origin is either ureteral bud failure or absence of the nephrogenic ridge. c. Associated findings include absent renal arteries, complete ureteral atresia in 50%, bladder atresia in 50%, Potter syndrome; also low birth weight, oligohydramnios, pulmonary hypoplasia, bowed limbs. Testes are undescended in 45%. d. Several genes, including PAX2/8, Gata3, and Lim1, play a critical role. 6. Unilateral renal agenesis b. Origin is probably ureteral bud failure; there is a familial trend. c. Associated findings include absent ureter with hemitrigone (50%), adrenal agenesis (10%), genital anomalies (20% to 40% in both sexes). 2) In males, the wolffian structures distal to the epididymal head are absent in 50%, including the body and tail of epididymis, vas, and seminal vesicles. 3) Cardiac (30%), gastrointestinal (GI) anomalies (25%), and skeletal (15%) are also present. d. If the single kidney is normal, no special precautions are required, and survival is not affected; management is focused on the genital, cardiac, GI, and skeletal abnormalities. 7. Supernumerary kidney (Figure 30-4) b. Origin is a combined defect of ureteral bud and metanephros. c. Associated findings are hydronephrosis (50%), common ureter (40%), duplex ureter (40%), and ectopic ureter or one ending in the pelvis of the ipsilateral kidney (20%). 1. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease b. Autosomal dominant transmission c. Adult type is the most common cystic disease in humans, with an incidence of 1 per 1250 live births, and accounts for 10% of all end-stage renal disease (ESRD). d. It usually presents between 30 and 50 years of age with pain, hematuria, and progressive renal insufficiency, but it is also seen in children. It rarely present in newborns. e. Intravenous urography (IVU) reveals irregular renal enlargement with calyceal distortion; ultrasound shows multiple cysts of variable sizes. f. Associated findings are liver cysts without functional impairment in one third of patients and berry aneurysms (aneurisms of the circle of Willis) in 10% to 40%, also cysts of pancreas, spleen, lungs, colonic diverticula, aortic aneurysms and mitral valve prolapse. g. Complications include uremia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and intracranial hemorrhage (9%). h. Management involves control of blood pressure (BP) and urinary infection, relief of cardiac failure, and eventually dialysis or transplantation. Some of these patients encounter issues with pain typically from renal capsular stretching by the cysts. i. Pathology: Rounded or irregular cysts are located in all parts of the nephron. 2. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease a. Chromosome 6, autosomal recessive b. Infantile type is rare (1 per 10,000 to 50,000 live births) and usually presents with bilateral flank masses in infancy, but it can present in childhood with renal or hepatic insufficiency. Historically mortality is 50%. c. IVU shows huge (12 to 16 times normal) kidneys with a pronouncedly delayed nephrogram and a characteristic, streaked appearance (“sunburst” pattern). d. It may be distinguished from hydronephrosis, renal tumor, and renal vein thrombosis by IVU and ultrasound (bright echoes on ultrasound). e. Associated findings are congenital hepatic (periportal) fibrosis (in all cases) and dilation of bile ducts with the degree of hepatic insufficiency varying inversely with the severity of renal disease and directly with the age of presentation; cysts elsewhere are uncommon. f. Complications are renal and hepatic failure, hypertension, and respiratory compromise in the newborn; patients usually die within the first 2 months of life. g. Although respiratory support, BP control, and dialysis can improve survival, patients will ultimately develop cirrhosis with all of the associated complications. h. Pathology is fusiform dilation of collecting ducts and tubules, resulting in small subcapsular cysts. 3. Medullary sponge kidney (tubular ectasia) is an adult disease pathologically characterized by enlarged tortuous collecting ducts and occasional tiny cysts in the pyramids (75% bilateral; incidence is 1 per 20,000). b. Complications: infection, stones, distal renal tubular acidosis, and hematuria. c. Medical management of calculi and infections is often required. d. One third of patients with hypercalcemia. 4. Medullary cystic disease (juvenile nephronophthisis) refers to a group of disorders with various genetic patterns characterized pathologically by bilateral small kidneys, attenuated cortex, atrophic and dilated tubules, medullary cysts, and some interstitial fibrosis. b. Medical management of renal failure can delay the need for transplant. c. Polydipsia and polyuria are in 80%; retinitis pigmentosa is in 16%. 5. Unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney is the most common cystic disease of the newborn (one in 1000 to 4000 live births) and the second most common abdominal mass in infants after hydronephrosis, including UPJO. a. The left kidney is more commonly involved, but there is no sex predilection or familial tendency. b. Origin is either (1) ischemic, from failure of the normal shift of vasculature as the kidney migrates, producing also the associated atretic ureter, or (2) failure of the ureteral bud to stimulate metanephric blastoma, or (3) representative of the extreme form of UPJO with atresia of the ureter early in development. c. Contralateral renal abnormalities are most common when the multicystic kidney is small and/or the ureteral atresia is low. VUR may be present in up to 20% of cases, but this may not be clinically apparent. d. Ultrasound is the most diagnostic study (multiple hypoechoic areas of various sizes without connections or dominant medial cyst and without identifiable parenchyma) because VUR commonly is present, Every child with a history of UTI should undergo voiding cystoscopy (VCUG). If there is less than confirmatory imaging on ultrasound, renal scintigraphy (DMSA or MAG3) will confirm the diagnosis with no flow or function present. e. Histopathology includes atretic artery, cysts, some solid central stroma, low cuboidal epithelium, some primitive nephrogenic structures, and occasionally immature glomeruli. f. In most, the cystic kidney usually does not enlarge as the child grows and thus becomes relatively less conspicuous. Most can be followed. Reports of hypertension are rare. Malignant transformation, previously feared, is exceedingly rare and not thought to be a clinical threat and is no higher risk than in normal kidneys Removal of the cystic kidney is now only recommended in those in whom the kidney has enlarged over time. 1. Calyceal diverticulum occurs in 4.5 per 1000 urograms. b. In approximately one third of patients, stones will form; some will become sites of persistent infection because of stasis; the rest remain asymptomatic. c. Treatment involves removal of stones, drainage of purulence, and marsupialization to the renal surface with closure of the collecting system and cauterization of the epithelium. 2. Hydrocalycosis is a rare lesion involving vascular compression, cicatrization, or achalasia of the infundibulum; it rarely requires any intervention. 3. Megacalycosis is a rare lesion involving all of one or both kidneys with dilated unobstructed calyces usually numbering more than 25 per kidney (normally 8 to 10 calyces per kidney). It may be confused radiographically with obstructive uropathy. b. Males 6:1 over females, only in Caucasians; X-linked recessive gene c. May be associated with stones or infection but in itself causes no deterioration of renal function 4. Infundibulopelvic stenosis may involve part or all of one or both kidneys. b. May be associated with dysplasia and lower tract anomalies (e.g., urethral valves) c. Commonly associated with VUR 5. UPJO is the usual cause of the most common abdominal mass in children (hydronephrosis). a. There is a 2:1 male predominance in children and left-sided predominance in all ages. b. Several possible causes, including segmental muscular attenuation or malorientation, true stenosis, angulation, and extrinsic compression (Figures 30-5 and 30-6). Crossing lower-pole vessels are present in approximately 20% to 30% of cases, but an intrinsic lesion (either noncompliant or nonconducting) is common. Lower-pole UPJO can occur in duplex ureters. Rarely secondary UPJO can follow severe VUR. In these cases, correction of the VUR may result in better upper drainage. c. Associated findings include reflux (5% to 10%), contralateral agenesis (5%), and contralateral UPJO (10%); rarely dysplasia, multicystic kidney, or other urologic anomaly. d. Many infants with UPJO will be identified in utero with routine prenatal screening ultrasounds. For the few who develop symptoms, symptoms and signs include episodic flank pain and/or mass, hematuria, infection, nausea and vomiting, and sometimes uremia. In infants, the flank mass may be the only sign, whereas the older child will exhibit any of the others; very often GI distress and poorly localized upper abdominal pain are the only symptoms. e. Radiologic findings are delayed excretion on the affected side with variable dilation of pelvis and calyces, or on ultrasound, multiple interconnected hypoechoic areas with dominant medial hypoechogenicity and identifiable cortical rim. There is usually some measurable function on renal scan. When function is good, the drainage is delayed even in the face of furosemide (Lasix) administration beyond 20 minutes. f. Prompt surgical repair is done by excision of the narrow segment and a spatulated anastomosis of the ureter to the tailored renal pelvis for symptomatic cases. If an associated obstructing lower-pole vessel is present, the vessel is placed posterior to the anastomosis (Figure 30-7). Most are diagnosed antenatally and can be followed with serial renal scan and ultrasound.

Congenital Anomalies

Upper urinary tract

Abnormalities of the kidney position and number

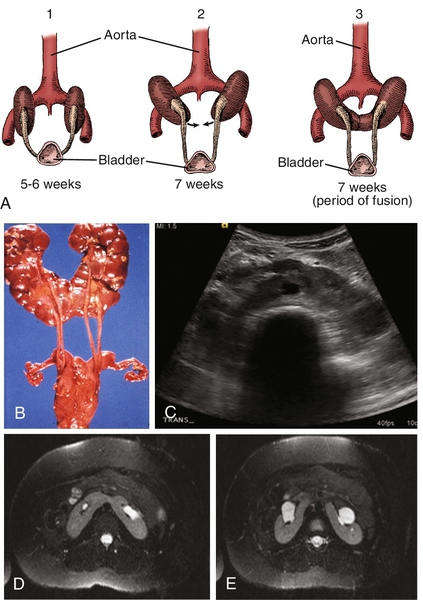

Cystic abnormalities of the kidneys (Table 30-1)

Collecting system abnormalities

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Congenital Anomalies

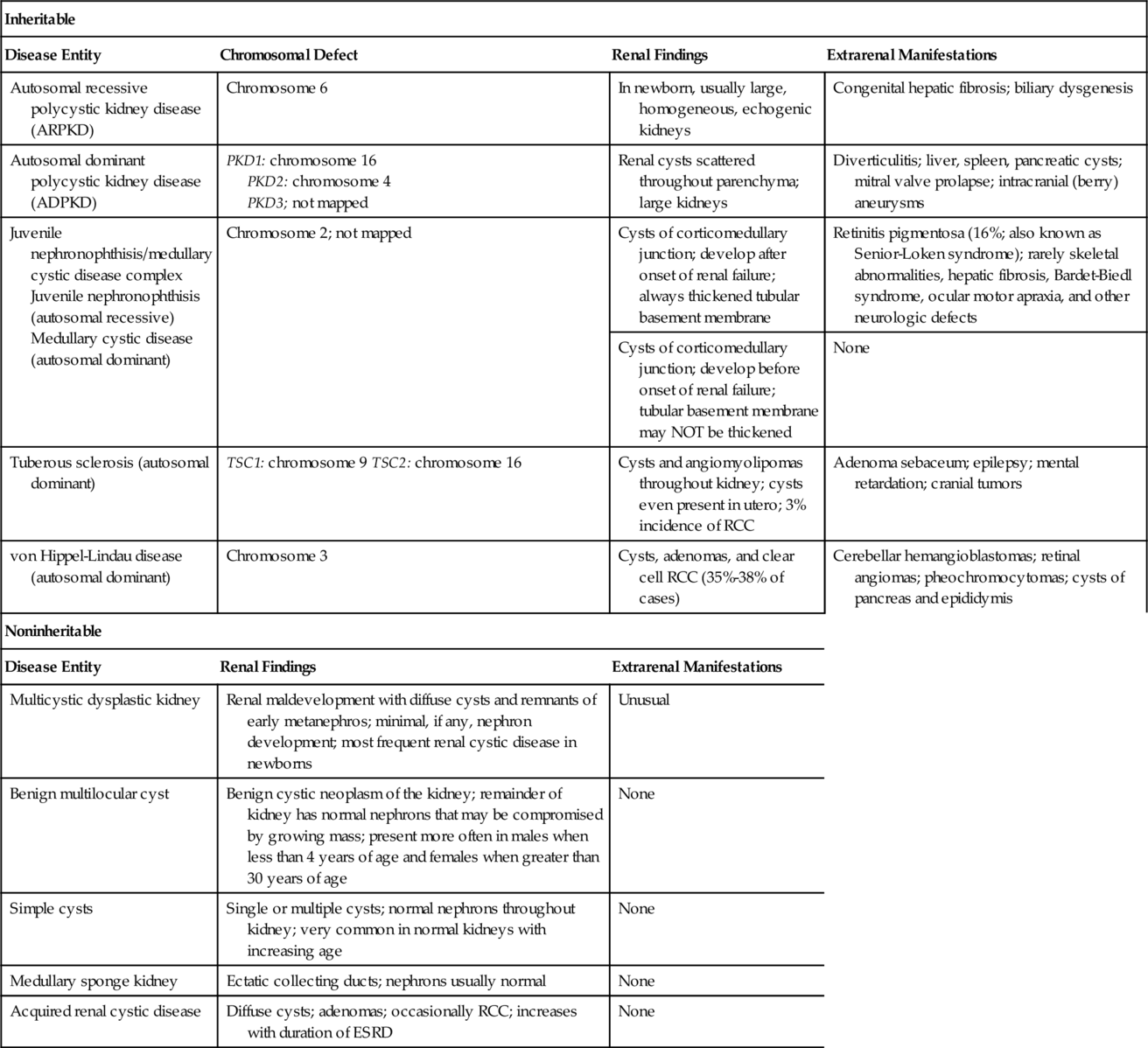

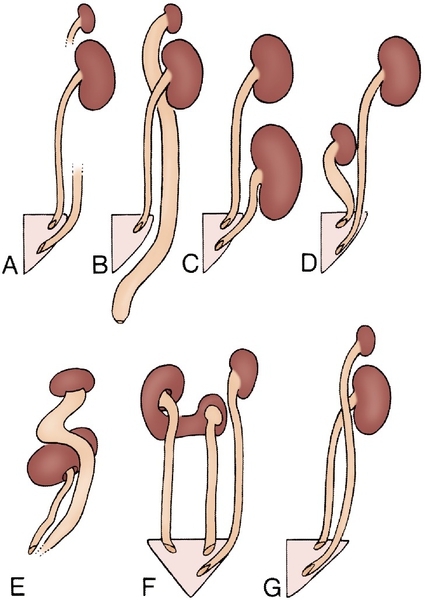

Figure 30-1 A to D, Four types of crossed renal ectopia. (From Shapiro E, Bauer SB, Chow JS: Anomalies of the upper urinary tract. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.)

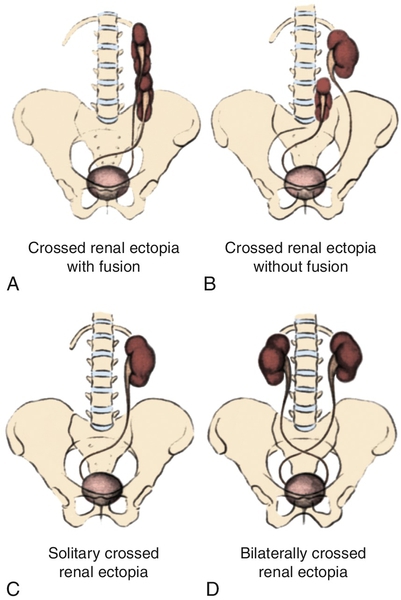

Figure 30-2 A to F, Six forms of crossed renal ectopia with fusion. (From Shapiro E, Bauer SB, Chow JS: Anomalies of the upper urinary tract. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.)

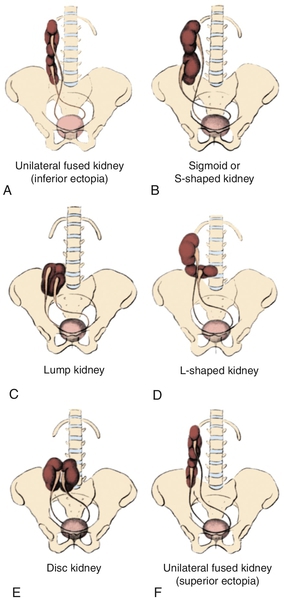

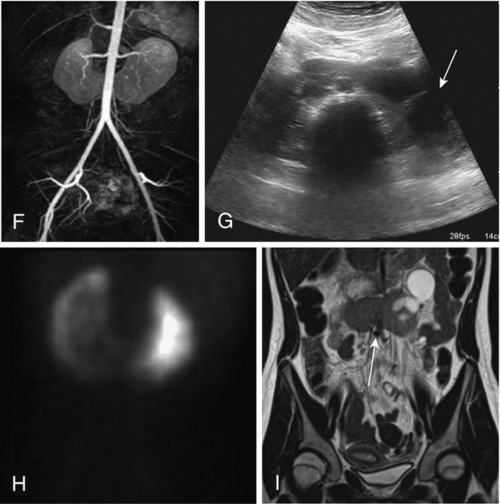

Figure 30-3 A, Embryogenesis of horseshoe kidney. The lower poles of the two kidneys touch and fuse as they cross the iliac arteries. Ascent is stopped when the fused kidneys reach the junction of the aorta and inferior mesenteric artery. B, Postmortem specimen showing horseshoe kidney with bilateral duplicated ureters. C, Ultrasonogram of horseshoe kidney at the level of the isthmus. D, Magnetic resonance urogram (MRU) shows axial T2 fat-saturated image at the level of the isthmus. E, Axial T2 fat-saturated image demonstrates extrarenal pelvis. F, Angiographic sequence shows variable blood supply to the kidney. G, Transverse ultrasonogram of 14-year-old girl with left flank pain found to have marked left hydronephrosis in a horseshoe kidney (arrow). H, MAG3 scan demonstrates left ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). I, Coronal T2 images of MRU show the isthmus (arrow) and severe left hydronephrosis. Reprinted in Shapiro E, Bauer SB, Chow JS: Anomalies of the upper urinary tract. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.)

(A from Benjamin JA, Schullian DM: Observation on fused kidneys with horseshoe configuration: The contribution of Leonardo Botallo [1564]. J Hist Med Allied Sci 5:315–326, 1950. after Gutierrez, 1931; B from Weiss, MA, Mills, SE: Atlas of genitourinary tract disorders, Philadelphia, 1988, JB Lippincott.

Figure 30-4 Rotation of the kidney during its ascent from the pelvis. The left kidney with its renal artery and the aorta are viewed in transverse section to show normal and abnormal rotation during its ascent to the adult site. A, Primitive embryonic position; hilus faces ventrad (anterior). B, Normal adult position; hilus faces mediad. C, Incomplete rotation. D, Hyperrotation; hilus faces dorsad (posterior). E, Hyperrotation; hilus faces laterad. F, Reverse rotation; hilus faces laterad. (A from Shapiro E, Bauer SB, Chow JS: Anomalies of the upper urinary tract. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders. B from Skandalakis JE, Gray SW: Embryology for surgeons: the embryological basis for the treatment of congenital defects, Philadelphia, 1972, WB Saunders.)

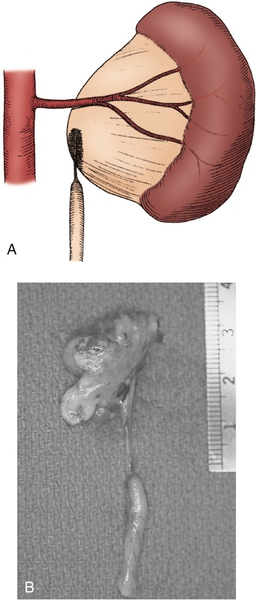

Figure 30-5 A, Intrinsic narrowing of upper ureter contributing to ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). B, Surgical specimen of nonfunctioning kidney with significant proximal ureteral narrowing. (From Carr MC, Casale P: Anomalies and surgery of the ureter in children. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.)

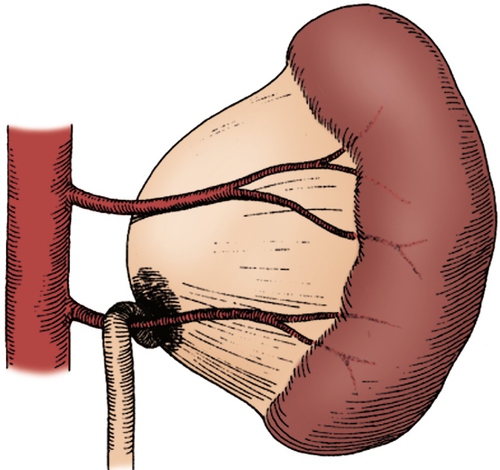

Figure 30-6 A lower pole crossing vessel contributes to significant kinking at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) and resultant intermittent obstruction. Often, when the ureter is mobilized, no evidence of intrinsic narrowing is found. Insertional anomaly and peripelvic fibrosis may also be present as secondary obstructive factors. (From Carr MC, Casale P: Anomalies and surgery of the ureter in children. In Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors: Campbell-Walsh urology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders.)

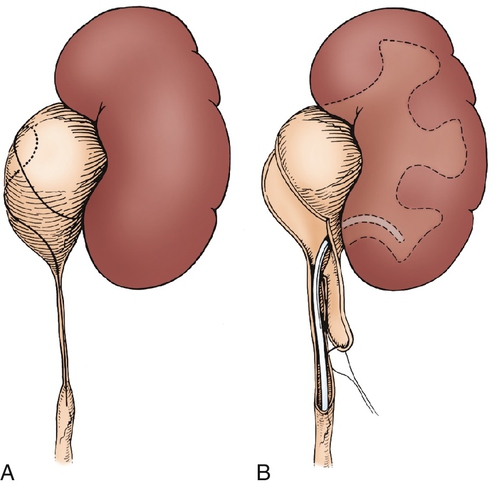

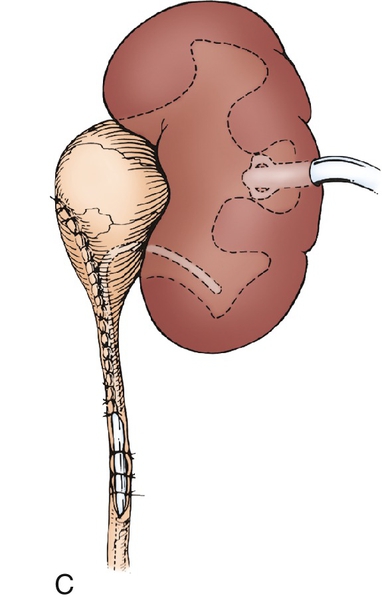

Figure 30-7 A, The intubated ureterotomy may be of value when a ureteropelvic junction obstruction is associated with extremely long or multiple ureteral strictures. A spiral flap is outlined and developed as described in. The ureterotomy incision will be carried completely through the long, strictured area or through each of the multiple areas of stricture. B,