Colon Cancer: Management of Locoregional Disease

Eric Van Cutsem

Andre D’Hoore

Caroline De Vleeschouwer

Jochen Decaestecker

Freddy Penninckx

Colon cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in the Western world. Every year, it is estimated that approximately 1 million new cases of colorectal cancer (CRC) are diagnosed. CRC is responsible for an estimated 400,000 to 500,000 deaths worldwide every year.

Seventy to 75% of patients with colon cancer present with localized disease. In these patients, surgery can be curative, but relapses after complete resection are frequent despite curative surgery leading to morbidity and eventual mortality. Colon cancer is a disease in which systemic failure is of primary importance. Metastases can occur at several sites: The liver, the peritoneum, and the lungs are the most frequent sites of metastatic disease, although other organs can also be affected. Locoregional recurrence occurs, although less frequently than metastases, and is more frequent in patients with tumor invasion of surrounding tissues (T4 tumor), tumor-associated perforation, or obstruction. Adjuvant strategies are therefore focused on preventing metastatic disease after surgical resection of the primary tumor.

Colon cancer is not uniformly fatal, and there are large differences in survival, depending on the stage of the disease. The pathological stage is currently the most important determinant of prognosis and is discussed in detail in Chapter 42. he classification system described by Dukes no longer fulfils the requirements of modern tumor staging. It does not take into account distant metastases, the number of lymph nodes involved, and carcinomas limited to the submucosa. The tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is currently recommended. The updated sixth edition stratifies colon cancer stages II and III further by use of the T stage and the N stage (Table 43.1) (1,2).

Recently, survival rates have been published from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results U.S. National Cancer Registry from January 1, 1991 through December 31, 2000, based on data from 119,363 patients according to the new AJCC sixth edition staging (3). Overall, 5-year colon cancer–specific survival for this entire cohort was 65.2% (3). Five-year colon cancer–specific survival by stage was 93.2% for stage I, 84.7% for stage IIa, 72.2% for stage IIb, 83.4% for stage IIIa, 64.1% for stage IIIb, 44.3% for stage IIIc, and 8.1% for stage IV cancer. Another large analysis based on the U.S. National Cancer Database showed a 5-year survival rate of 59.8% for stage IIIa, 42.0% for stage IIIb, and 27.3% for stage IIIc colon cancer in 50,042 patients from 1987 to 1993 (4).

The initial diagnosis of colon adenocarcinoma is made by colonoscopic examination and biopsies of the tumor. The diagnosis and staging is discussed in detail in Chapter 42.

Surgery for Colon Cancer

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for patients with colon adenocarcinoma and has a curative intent in patients with locoregional disease. The goal of surgical treatment is a wide resection of the primary tumor with all locoregional lymph nodes that follow the arterial blood supply of the colonic segment. The essential role of the surgeon has been recognized, and in the absence of standardized operation techniques, the surgeon is an important variable influencing the oncologic outcome. Most patients will undergo elective surgery, and mechanical bowel cleaning has historically been considered an essential component of the preoperative preparation of the patient. This has, however, recently been questioned (5), and the evidence that suggests that luminal cleaning is not essential to allow a safe colonic anastomosis is growing. Occasionally, emergency resection is required in patients with colonic obstruction. In patients with an imminent blowout of the caecum, either an on-table lavage or a subtotal colectomy can be performed. In critically ill patients, a Hartmann-type resection can be the best option.

Clinical T4 tumors directly invading other structures and organs require a more complex “en bloc” resection to obtain an adequate resection margin. Local inoperability in colon cancer is rare and relates to direct invasion of the tumor of the corpus of the pancreas or extensive regional lymph node spread into the mesentery of the small bowel. Exceptionally, a neoadjuvant preoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy may be considered so the resection can be performed with greater chance of clear margins and/or organ preservation. A “temporary” ileocolic bypass can be performed to avoid bowel obstruction during this treatment.

It is seldom that the medical condition of the patient can prohibit a surgical intervention.

The standard curative colon resection for adenocarcinoma is based on resection with adequate proximal and distal margins and a regional lymphadenectomy. About 10 cm of the proximal and distal colon is to be resected in order to reduce the risk of leaving paracolic nodes. Preoperative colonoscopy with tattooing is recommended in small, early lesions in order to facilitate intraoperative localization and decision

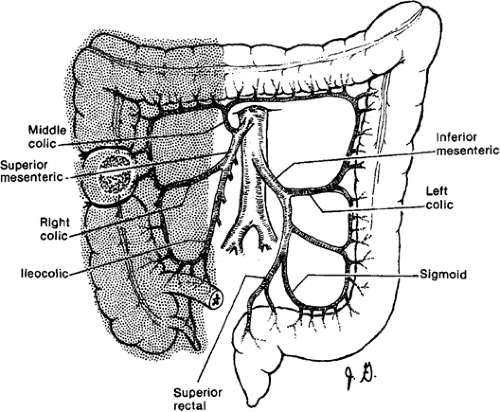

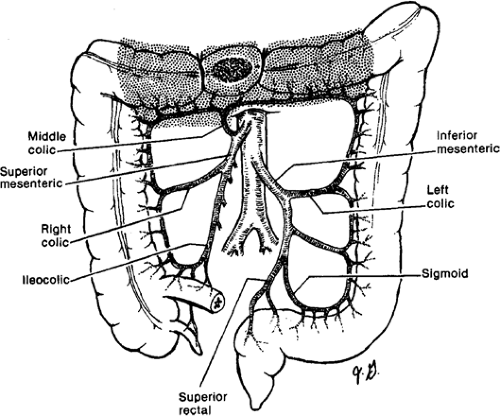

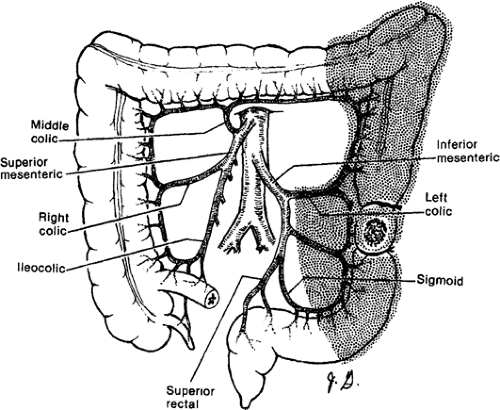

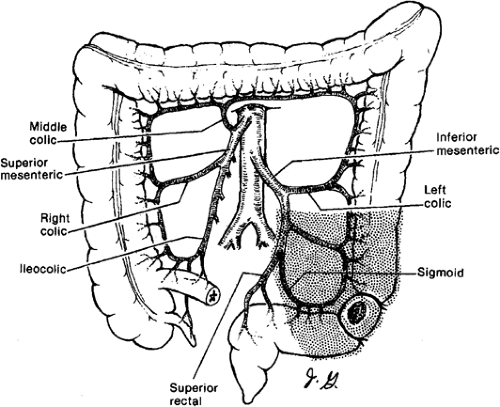

making. The regional lymphadenectomy is based on the arterial blood supply to the particular portion of the colon. A “no touch” mobilization and high (central) ligation of the vessels of the tumor-bearing colon segment are part of the surgical standards. Surgeons who advocate the “no touch” technique ligate the lymphovascular structures prior to mobilization. A lesion in the right colon requires removal of mesentery with ileocolic and right colic arteries with the right branch of the middle colic artery. Transverse colon lesions require resection of the mesentery with the middle colic artery. In advanced stages, lymph nodes can be found at the base of the gastroepiploic vessels, and a radical omentectomy seems to be indicated in these cases. Lesions in the descending colon require removal of the left colic artery, as well as the left branch of the middle colic artery and its associated mesentery. Sigmoid colon lesions require removal of the superior rectal artery and sigmoid branches with a colorectal anastomosis (anterior resection). The presence of a lesion at watershed areas of vascular supply (lesions at the hepatic or splenic flexure) can therefore indicate more extensive resections. New evidence points at the importance to obtain a broad and intact “mesocolic” resection to avoid locoregional recurrence (in agreement with the concept of total mesorectal resection in rectal cancer) (Figs. 43.1,43.2,43.3,43.4).

making. The regional lymphadenectomy is based on the arterial blood supply to the particular portion of the colon. A “no touch” mobilization and high (central) ligation of the vessels of the tumor-bearing colon segment are part of the surgical standards. Surgeons who advocate the “no touch” technique ligate the lymphovascular structures prior to mobilization. A lesion in the right colon requires removal of mesentery with ileocolic and right colic arteries with the right branch of the middle colic artery. Transverse colon lesions require resection of the mesentery with the middle colic artery. In advanced stages, lymph nodes can be found at the base of the gastroepiploic vessels, and a radical omentectomy seems to be indicated in these cases. Lesions in the descending colon require removal of the left colic artery, as well as the left branch of the middle colic artery and its associated mesentery. Sigmoid colon lesions require removal of the superior rectal artery and sigmoid branches with a colorectal anastomosis (anterior resection). The presence of a lesion at watershed areas of vascular supply (lesions at the hepatic or splenic flexure) can therefore indicate more extensive resections. New evidence points at the importance to obtain a broad and intact “mesocolic” resection to avoid locoregional recurrence (in agreement with the concept of total mesorectal resection in rectal cancer) (Figs. 43.1,43.2,43.3,43.4).

Table 43.1 Stages as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer in relation to survival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Occasionally, the presence of synchronous colon cancers or multiple colon adenomas that cannot be resected endoscopically, or information consistent with the hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome, will indicate a subtotal or total colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. Prophylactic oophorectomy seems to be of no survival benefit; only infiltrated or grossly abnormal ovaries have to be removed.

The appropriate extent of colonic resection and lymphadenectomy has been controversial. The rationale for an

extended lymphadenectomy is that a wider dissection removes more lymph nodes with possible metastatic deposits and thereby increases the chances of cure. Although randomized trials comparing extended with limited lymphadenectomy have not shown that an extended lymphadenectomy improves the prognosis compared to a limited resection, there is a general agreement that a large number of lymph nodes should be recovered. It is often agreed that at least 12 lymph nodes should be removed. In the Intergroup Trial INT-0089 of adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk patients with stage II and stage III colon cancer, a secondary analysis demonstrated that examining more nodes was associated with increase of survival in both node-negative and node-positive patients (6). In this study, the median number of nodes removed at colectomy was 11 (range 1–87). This is similar to the lymph node yield in colectomy specimen after “standardized resection” reported in randomized trials comparing open and laparoscopic resections for colon cancer: 11.1–11.1 (7), 12.1–11.1 (8), 12–12 (9), and 10–10 (10). However, using a mathematical model based on data from the Intergroup Trial INT-0089, it was

suggested that more than 40 nodes would need to be examined in a patient with an early stage (T1/T2) cancer for the probability to be 85% that the patient is node negative. With 18 nodes, the probability was only 25% of being truly node negative. For T3 and T4 tumors, 40 and 30 nodes, respectively, would need to be examined to achieve an 85% probability of being node negative. When 18 lymph nodes are examined, the probability of being truly node negative is >25% for T3 tumors and >50% for T4 tumors. On the basis of this analysis, a strong effort must be made to improve the surgical technique and our methods of pathological analysis (11). Special techniques such as fat clearance or submission of the entire mesenteric tissue for pathological examination after manual node dissection have been evaluated. These techniques are labor intensive and do not seem to upstage a clinically relevant number of hematoxylin and eosin node-negative patients (12). Also, sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping has been applied and found to be safe and feasible in colon cancer after appropriate training (13,14). It has the advantage of a more focused pathological examination of the nodes that are identified as sentinel lymph nodes by using techniques such as immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). As many as 18% to 25% of patients have been upstaged from stage II to stage III after metastatic disease was detected in the sentinel node (15,16).

extended lymphadenectomy is that a wider dissection removes more lymph nodes with possible metastatic deposits and thereby increases the chances of cure. Although randomized trials comparing extended with limited lymphadenectomy have not shown that an extended lymphadenectomy improves the prognosis compared to a limited resection, there is a general agreement that a large number of lymph nodes should be recovered. It is often agreed that at least 12 lymph nodes should be removed. In the Intergroup Trial INT-0089 of adjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk patients with stage II and stage III colon cancer, a secondary analysis demonstrated that examining more nodes was associated with increase of survival in both node-negative and node-positive patients (6). In this study, the median number of nodes removed at colectomy was 11 (range 1–87). This is similar to the lymph node yield in colectomy specimen after “standardized resection” reported in randomized trials comparing open and laparoscopic resections for colon cancer: 11.1–11.1 (7), 12.1–11.1 (8), 12–12 (9), and 10–10 (10). However, using a mathematical model based on data from the Intergroup Trial INT-0089, it was

suggested that more than 40 nodes would need to be examined in a patient with an early stage (T1/T2) cancer for the probability to be 85% that the patient is node negative. With 18 nodes, the probability was only 25% of being truly node negative. For T3 and T4 tumors, 40 and 30 nodes, respectively, would need to be examined to achieve an 85% probability of being node negative. When 18 lymph nodes are examined, the probability of being truly node negative is >25% for T3 tumors and >50% for T4 tumors. On the basis of this analysis, a strong effort must be made to improve the surgical technique and our methods of pathological analysis (11). Special techniques such as fat clearance or submission of the entire mesenteric tissue for pathological examination after manual node dissection have been evaluated. These techniques are labor intensive and do not seem to upstage a clinically relevant number of hematoxylin and eosin node-negative patients (12). Also, sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping has been applied and found to be safe and feasible in colon cancer after appropriate training (13,14). It has the advantage of a more focused pathological examination of the nodes that are identified as sentinel lymph nodes by using techniques such as immunohistochemistry and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). As many as 18% to 25% of patients have been upstaged from stage II to stage III after metastatic disease was detected in the sentinel node (15,16).

A 25% recurrence rate in patients with node-negative CRC suggests that current staging practices are inadequate. With an adequate surgical technique, this may be related to understaging. Thus, micrometastases or free tumor cells have been searched and identified in blood, bone marrow, and lymph nodes (LNs). Micrometastases in LNs are defined as >0.2 mm but <2 mm, and isolated tumor cells as <0.2 mm. In some institutions, all patients with isolated tumor cells and micrometastasis are receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Instead of performing the rather expensive, labor-intensive, and time-consuming multiple sections with immunohistochemical staining or PCR on all LNs in the operative specimen, a more focused analysis of the SLNs has been applied in colon cancer. SLNs are defined as the first LNs along the direct lymphatic pathway from the primary tumor. They are identified by injecting vital blue dye close to the tumor site. Lymphatic mapping with SLN identification has been shown to be reproducible after appropriate training (13). It does not, however, replace standard pathological examination of the locoregional LNs.

The SLN concept aims to enable a pathologist to analyze more meticulously one or a few LNs harboring the highest risk of metastatic disease (14). SLN assessment has been applied for colonic cancer and resulted in a high rate of node identification and pathological upgrading. There is, however, no conformity regarding the procedure (in vivo and ex vivo staining), and there is too little evidence to allow its recommendation.

Blood loss should be minimized during surgery with meticulous attention to hemostasis in order to avoid the immunosuppressive effect associated with transfusions and to not increase the risk of recurrence.

Location of Laparoscopic Colonic Cancer Resection

The interest in the use of minimally invasive surgical techniques to treat benign disease of the gastrointestinal tract has been extended to colonic neoplasms. The early enthusiasm was tempered by cautionary reports on high occurrences of port-site metastases. A small series presenting an alarming 21% incidence of port-site metastases in 1994 initiated a virtually worldwide moratorium of laparoscopic colectomy for cancer outside the ongoing prospective randomized trials. More basic research was begun to elucidate the problem because there was a potential danger that the CO2 pneumoperitoneum served as a potential vector for exfoliated tumor cells, which then could be trapped within the small wounds of the trocar sites. It became progressively clear that port-site metastasis was a dramatic side effect of the learning curve. The actual port-site recurrence rate is <1% and comparable with the rate of wound recurrences noted after open surgery. Recent evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates no oncosurgical disadvantage of laparoscopic colon cancer resection compared to an open resection.

In 2002, the first results of a prospective randomized trial in 219 patients with colon cancer (the so-called Barcelona Trial) were published and generated a lot of interest and enthusiasm. The oncologic outcome not only seemed comparable to the open approach but also a significant reduction in local recurrence and an improved diseasefree survival (DFS) in stage III patients was found (7). These findings fit well with data from experimental studies, suggesting that a decrease in perioperative immunosuppression, as a result of a laparoscopic approach, could lead to a decrease in tumor spread. In 2004, the 3-year results of a U.S. multicenter prospective randomized trial on laparoscopic versus open surgery (COST Trial: Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group) in 872 patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon showed a similar DFS and tumor recurrence rate in all stages (9). A prospective randomized trial from Hong Kong focused on the outcome of 403 patients with rectosigmoid adenocarcinoma and found no difference in survival or in DFS (8). The conversion rate of laparoscopy to open laparotomy varies between 11% and 23% in the randomized controlled trials and is most often related to tumor characteristics. The postoperative morbidity is lower in the laparoscopic group, mainly related to a lower rate of wound complications and complications in older and compromised patients. Laparoscopic colectomy is associated with decreased postoperative pain, faster ileus resolution, shorter hospitalization, and improved cosmesis when compared with open colectomy. The postoperative mortality is similar in both groups. Hospital stay is shorter in the laparoscopic group. Thus, the laparoscopic technique has become a valid alternative to open laparotomy for resection of colon cancer. The previously mentioned trials have been criticized because evidence-based principles of fast track (open) surgery were not described or implemented, inducing a potential bias in early outcome results (17). Limitations of the laparoscopic approach include the technical requirements of advanced laparoscopic skills and training, increased operative time, and equipment costs. Surgeons performing laparoscopic colectomy should be adequately experienced and certified to ensure successful outcomes. Despite these limitations, patient recovery benefits may offset the increased operative costs and result in improved cost effectiveness overall.

Adjuvant Treatment

The standard adjuvant treatment of colon cancer consists of chemotherapy. Although certain patients with colon cancer are at higher risk for local recurrence, the administration of postoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy has not been studied systematically in randomized studies. The published reports suggesting a benefit of postoperative radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in selected cases are nonrandomized single-institution retrospective analyses.

Although stage II and III colon cancers have significantly different recurrence and survival rates, most randomized studies to date have recruited both stage II and III patients, often with preplanned subgroup analyses, in an attempt to determine the efficacy of chemotherapy by stage. In stage I colon cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy is not indicated in view of the good prognosis of patients with stage I colon cancer.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer

Since the mid-1990s, it is generally recommended to treat patients with stage III or lymph node-positive colon cancer with adjuvant chemotherapy. It has indeed been shown that adjuvant chemotherapy decreases the relapse rate and improves the survival in stage III colon cancer. It has been reported that the number of patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy increased in the United States from 39% in 1991 to 64% in 2002 (18). This analysis also demonstrates that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy was not homogeneously incorporated in every patient population, at least in the first period of observation (18). Patients older than 80 years were less frequently treated with adjuvant chemotherapy, patients with more invasive tumors and a greater number of involved lymph nodes were more likely to receive adjuvant therapy, and women received adjuvant therapy less frequently than men. The perception of greater potential risk because of comorbidities among elderly patients and the perceived greater potential benefit of adjuvant therapy among patients with more aggressive disease help explain the first two observations, but there is no clear reason for the gender differences observed (19). The central issue regarding adjuvant chemotherapy is the difficulty in assessing its real benefit for an individual patient. The recommendation is generally based on the proof of efficacy in a selected population at risk for disease recurrence. The decision-making process is always complex. The physician’s understanding of the potential benefit is influenced by his or her own prejudice and the patient’s confidence is influenced by beliefs and fear. Factors such as comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and low adherence to therapy are among the well-described causes for not using adjuvant chemotherapy. Ongoing studies of molecular markers for CRC should help determine which patients benefit most from adjuvant therapy.

Important progress has been made in our knowledge on the options for adjuvant chemotherapy and on the outcome of patients with colon cancer treated with postoperative chemotherapy.

5-Fluorouracil/Levamisole for 1 Year

The intergroup trial (INT-0035) was the first large-scale study to demonstrate a significant effect of postoperative adjuvant treatment in patients with stage III colon cancer. This trial randomized 1,296 patients with stage II and III cancer (929 with stage III cancer) to one of the three arms:

Surgery alone

Surgery plus 12 months of levamisole

Surgery plus 12 months of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and levamisole

The study showed a 15% absolute reduction (±40% relative reduction) in the risk of recurrence and a 16% absolute reduction (33% relative reduction) in the overall death rate with a combination of surgery plus 5-FU/levamisole in patients with stage III colon cancer (20,21). The Netherlands Adjuvant Colorectal Cancer Project (NACCP) also demonstrated efficacy of 5-FU/levamisole compared to no adjuvant treatment in a randomized trial of patients with stage II and III CRC (22). The 5-year survival rate was significantly higher in the adjuvant treatment arm: 68% versus 58%.

5-FU/Folinic Acid for 6 Months

A number of studies in the 1990s have shown the efficacy of 5-FU modulated by folinic acid (FA) when compared with no postoperative treatment. The Canadian and European consortium trial (International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of Colorectal Cancer Trials [IMPACT]) is a combined analysis of the three trials that compared adjuvant treatment with high-dose 5-FU/FA with no treatment in nearly 1,500 patients. In this study, a 22% relative risk reduction in mortality at 3 years in Dukes’ C patients has been reported (23). An Italian study that was similar in design, but smaller, showed a 39% reduction in mortality for the patients treated with 5-FU/FA (24). A North Central Cancer Treatment Group

(NCCTG) trial established the efficacy of 6 months adjuvant therapy with 5-FU/low-dose FA compared with observation after surgery: 74% versus 63% of patients were alive at 5 years (25). The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) protocol C-03 indicated a DFS (73% vs. 64%) and overall survival (84% vs. 77%) advantage for 5-FU/FA compared with MOF (methyl-CCNU, Oncovin, 5-FU) at 3 years for patients with Dukes’ stage B and C colon cancer (26). The control arm in this study (MOF) had previously shown a borderline survival advantage over surgery alone in the adjuvant setting.

(NCCTG) trial established the efficacy of 6 months adjuvant therapy with 5-FU/low-dose FA compared with observation after surgery: 74% versus 63% of patients were alive at 5 years (25). The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) protocol C-03 indicated a DFS (73% vs. 64%) and overall survival (84% vs. 77%) advantage for 5-FU/FA compared with MOF (methyl-CCNU, Oncovin, 5-FU) at 3 years for patients with Dukes’ stage B and C colon cancer (26). The control arm in this study (MOF) had previously shown a borderline survival advantage over surgery alone in the adjuvant setting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree